10 Applied Leadership Development through FFA

Laura L. Greenhaw and Paula Faulkner

Setting the Stage

Sherry and Jose teach agriculture in a high school with a student population of approximately six hundred. Nearly half of the students in the school are enrolled in at least one agricultural education course. Sherry recently submitted a purchase order for program affiliation FFA membership so all students enrolled in an agricultural education course will be members of the FFA. Although their FFA chapter has utilized program affiliation membership previously, the new principal questions the purchase order, stating that students in other clubs must pay their own dues to participate in extracurricular activities. Sherry and Jose schedule a meeting with their new administrator to explain how FFA is an intracurricular component of the holistic agricultural education program. They prepare several examples that demonstrate FFA is fundamental for teaching and learning in agricultural education.

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, learners should be able to:

- Explain FFA as an intracurricular component of the complete agricultural education model.

- Describe the structure and components of FFA.

- Identify competencies taught through FFA activities.

- Illustrate efforts and opportunities for diversity and inclusion in FFA.

- Utilize FFA programs and activities as experiential learning opportunities for learners.

Introduction

FFA is a national organization that prepares members for premier leadership, personal growth, and career success through school-based agricultural education. The official name is the National FFA Organization. The letters “FFA” stand for Future Farmers of America, an important part of our history and heritage.

FFA develops youth with career and leadership development and helps them discover their talent through hands-on, minds-on experiences, giving them the tools for future success.

Former FFA members are teachers, scientists, veterinarians, government leaders, entrepreneurs, financial professionals, international business leaders, and professionals in many fields (National FFA Organization, 2021).

Overview

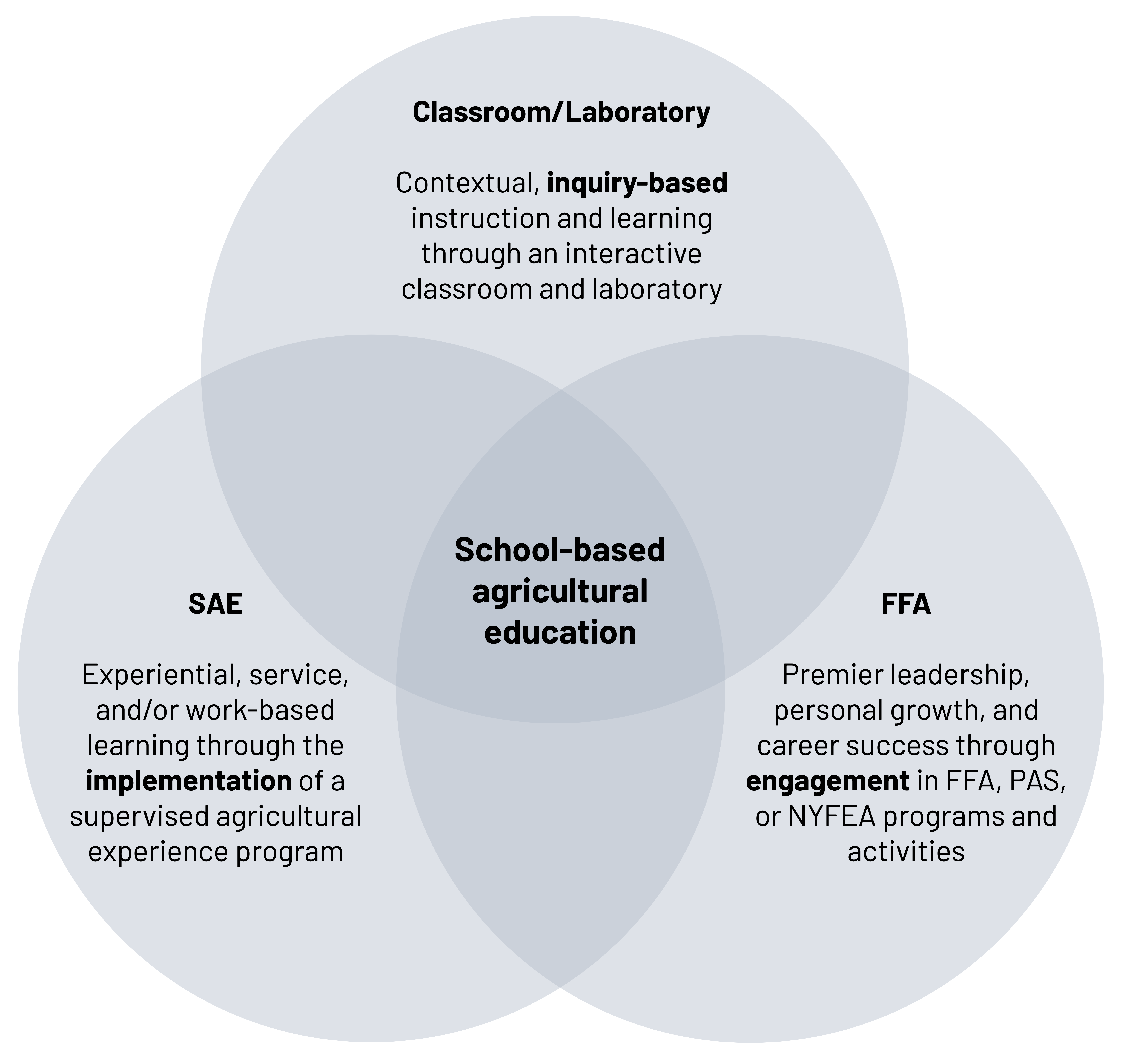

In 1988, the National Academy of Sciences Committee on Agricultural Education in Secondary Schools published Understanding Agriculture: New Directions for Education. Authors described secondary vocational agriculture programs as consisting of three parts, including “classroom and laboratory instruction, supervised occupational experiences (SOEs), and membership in the National FFA” (p. 2). More than three decades later, we continue to reference these three components, albeit with slightly modified language. Today, school-based agricultural education (SBAE) is grounded in a three-circle model that includes the classroom and laboratory, Supervised Agricultural Experience (SAE), and FFA (figure 10.1). FFA, the student organization, is a unique component of the three-circle model designed to teach and develop learners’ “premier leadership, personal growth, and career success” (The National FFA Organization, 2021). Through a variety of events, competitions, awards programs, conferences, degrees, and other methods, the FFA infuses value in all learners’ education. When combined with classroom and laboratory instruction and SAE projects, FFA connects, reinforces, and extends learning through simultaneous practice of leadership and technical agricultural knowledge, skills, and abilities.

In this chapter, we will discuss how FFA is an intracurricular component of a comprehensive SBAE program, describe the structure and components of FFA, identify competencies taught through FFA, illustrate diversity and inclusion efforts and opportunities in FFA, and demonstrate how to utilize FFA as an effective teaching strategy.

FFA Is Intracurricular

Intracurricular means “within the curriculum.” Unlike many other school organizations students can engage in outside of class, FFA is not an extra component of the educational experience. Rather, it is an equal contributor to the whole agricultural education program, integrated with classroom and laboratory instruction and supervised agricultural experience (SAE). Why is FFA different from extracurricular programs? One important difference is that the federal government recognizes the National FFA Organization as a crucial component of SBAE.

The National FFA Organization received a federal charter in 1950 when the US Congress passed Public Law 81-740 (FFA, 2019a). The law established FFA as a vital and inseparable component of SBAE. The charter was revised in 1998 and again in 2019, being signed into law most recently by President Donald Trump. Public Law 116-7, the “National FFA Organization’s Federal Charter Amendments Act,” reiterates that FFA is an integral component of agricultural education. The National FFA Organization’s federal charter clearly and inextricably links the organization to the US Department of Education, solidifying its critical role as one of the components in the three-circle model of agricultural education. The National FFA Board of Directors, National FFA staff, and a team of annually elected student officers lead the National FFA Organization. It is important to note that the National FFA Board of Directors, who serve as the governing body of the organization, includes the US secretary of education or the secretary’s designee who has experience in agricultural education, the FFA, or career and technical education (FFA, 2019b). Additionally, the charter provides federal authority for the US Department of Education and the US Department of Agriculture to work cooperatively in ensuring the sustainability of our nation’s agriculture industry. In the most recently passed iteration of the charter, the first purpose of the FFA is “to be an integral component of instruction in agricultural education, including instruction relating to agriculture, food, and natural resources” (FFA Federal Charter, 2019, p. 1). The charter makes it clear that FFA is fundamental to teaching and learning in agricultural education programs and that all learners enrolled in agricultural education courses should have access to and be engaged through FFA learning experiences and opportunities.

School-based agricultural education should directly support and advance the agriculture, food, and natural resources industry (FFA Federal Charter, 2019). This requires each teaching component (classroom/laboratory, SAE, and FFA) to be informed by local, state, regional, and national industry needs. Let’s consider an example.

Keisha teaches in a small public school in a rural area in the Southwest in the United States. Much of the local agriculture industry is traditional beef cattle production. The region also supports a significant amount of hunting, including several big game outfitters. Appropriately, Keisha has worked with her administration and school board to offer classes including science of large agriculture animals, agricultural economics and business management, environmental science and natural resources, science of food products and food processing, and science of wildlife and forestry management. She collaborates with local stakeholders to develop and support SAE opportunities for her students, such as ownership SAEs in beef and alfalfa production, placement SAEs at meat processing and taxidermy businesses, and research SAEs on controlled burns and wildlife management strategies.

Finally, Keisha incorporates FFA competitions and events into her curriculum. Students compete in several career and leadership development events, apply for proficiency awards, attend conferences and conventions, and develop an annual program of activities that reflects the culture of the area and the developmental interests of the students. How do we know that Keisha is using FFA to teach her students? Each of the FFA activities compliments and supports the classroom/laboratory instruction and SAE opportunities. Keisha’s students compete in livestock evaluation, meats evaluation and technology, farm and agribusiness management, environmental and natural resources, agricultural sales, and agricultural technology and mechanical systems Career Development Events. They apply for proficiency awards corresponding to their SAEs, and several students conduct and present agriscience fair projects developed from assessing and addressing local industry needs. Keisha works hard to ensure students experience a comprehensive education in her program, through a combination of classroom/laboratory instruction, SAE, and FFA.

FFA Is Experiential Learning

John Dewey believed that knowledge was constructed through real-life experiences in the social environment. Teachers are responsible for facilitating learning experiences and organizing the content to be learned within those real-life experiences. The social environment learning occurs in is paramount, according to Dewey, and social interactions should be carefully planned to facilitate the development of relationships, particularly those between adults and youth (Roberts, 2003). Dewey also believed that learners should acquire knowledge through their own personal experiences rather than have it dictated to them from outside sources such as textbooks or experts. Knowledge gained from past experiences, then, is used to teach about the present. Equally important is the organization of content for the learner. Subjects should not be isolated but integrated so that the learner makes connections between the content and real life where knowledge and skills are used simultaneously. For example, in real life, interpersonal skills are used simultaneously with technical skills by Extension agents working with farmers and ranchers to improve their crop yield.

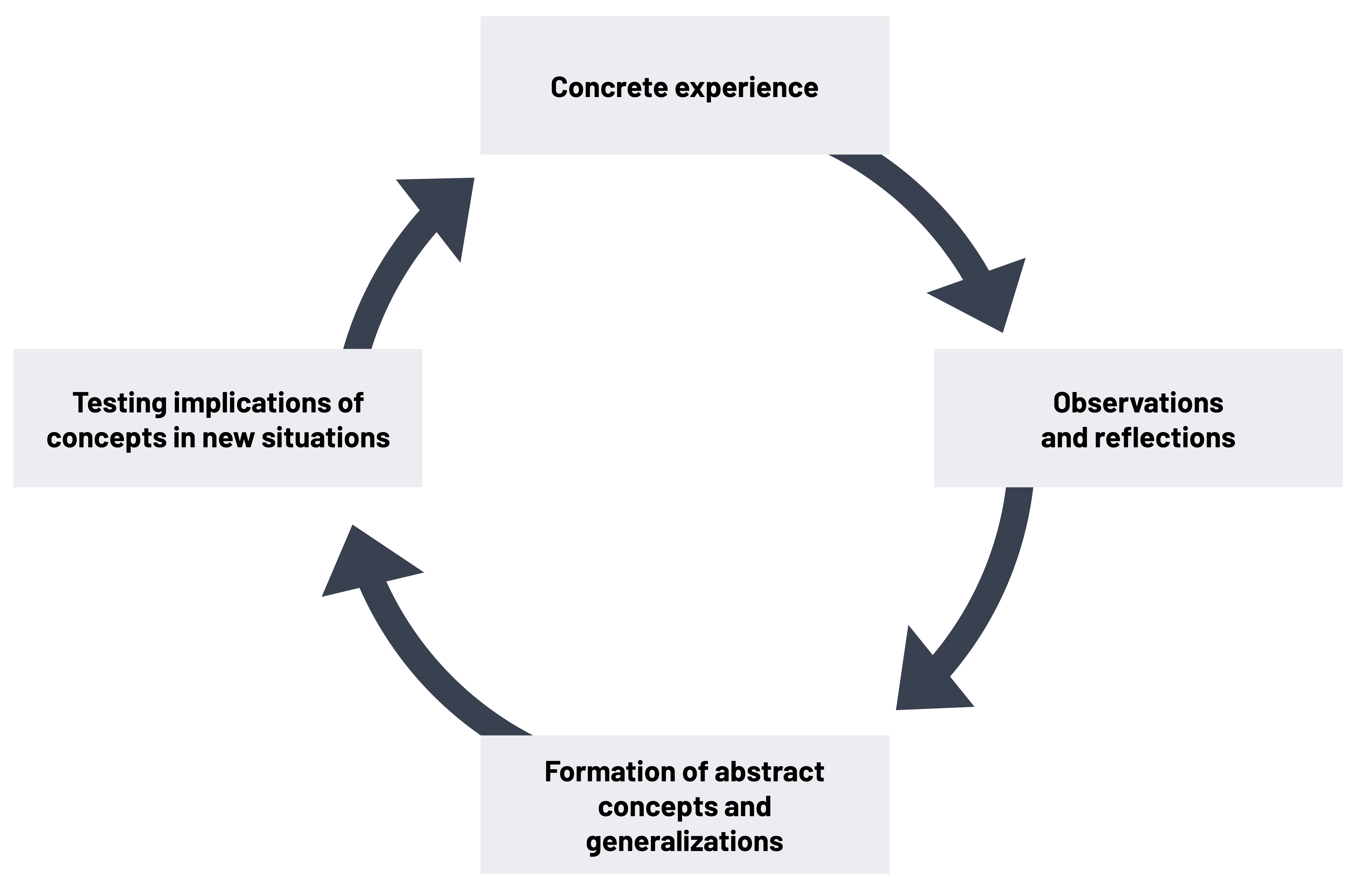

Like Dewey, Kolb (1984) defines learning as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (p. 41). According to Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory, learners progress through a four-part cycle to transform experience into knowledge. First, learners encounter new experiences or reinterpret past experiences. Then, they reflect on their experience, particularly how it may differ from their previous understanding. Abstract conceptualization follows, resulting in a new or modified idea or understanding. Finally, a learner actively experiments with their new idea or concept. (See figure 10.2.)

Experiential learning has been a foundational tenant of agricultural education since its inception (Baker et al., 2012). FFA provides a wide variety of experiential learning opportunities to engage learners at varying levels of readiness. The teacher should select experiences that situate learning in the context of local, state, regional, and national agriculture, food, and natural resources systems so learners can draw from their own experiences to build and expand knowledge and skills.

Moreover, as a student organization, FFA provides the social environment Dewey believed was so critical to learning. Although intracurricular, FFA activities often occur outside the classroom and can involve external stakeholders, thus fostering positive adult-youth relationships. Finally, these experiences demand learners use knowledge from multiple subjects at the same time, applying technical content coupled with leadership and interpersonal knowledge and skills.

Although FFA provides a well-built vehicle for learning in agricultural education, the burden of keeping the vehicle on the road to learning lies with the teacher. “Teachers must be present and mindful throughout the experiential learning process to guide and direct the learning process” (Baker et al., 2012, p. 7). The teacher is responsible for ensuring experiences are educative, because, as Dewey argued, not all experiences are (Roberts, 2003). The agricultural educator shoulders two responsibilities in Dewey’s experiential learning model: knowing the subject matter and knowing the learner. Further, a teacher must skillfully guide the learner through each phase of Kolb’s model (Baker et al., 2012). Therefore, planning is essential to creating worthwhile learning experiences. This requires the teacher to:

- Understand learners’ current knowledge,

- Determine appropriate learning environments,

- Allow the correct amount of learner autonomy,

- Accurately estimate learner readiness such that educational experiences are not beyond the scope of learners’ current ordinary life experiences,

- Organize learning experiences toward a specific end or outcome,

- Facilitate learners’ full extraction of meaning from experiences so they can apply the knowledge to future situations, and

- Guide educational experiences in a way that fosters students’ life-long learning capabilities (Roberts, 2003).

In the following sections, we will explore specific FFA learning experiences teachers can use to plan and guide learners through the experiential learning process. We begin with the structure of the FFA.

The FFA Organizational Structure

The National FFA Organization is structured on three levels (FFA, 2021). Learners can engage in activities and experiences through their local FFA chapter, their state association, and at the national level. The National FFA Organization staff work with a board of directors, six student national officers, national convention delegates, and agricultural education stakeholders to serve and support over 760,000 student members. All fifty states as well as Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands have state associations that charter local FFA chapters. As of 2020, nearly nine thousand local FFA charters had been granted.

While all three levels function under the National FFA Organization’s constitution and bylaws, state associations are led by their annually elected student officers and advised by the state supervisor of agricultural education. State associations have the autonomy to create unique learning opportunities that best fit their state’s needs, including competitions, awards, programs, and leadership structures within the bounds of the National constitution and bylaws. Likewise, local FFA chapters are led by annually elected chapter officers and are advised by the agriculture teacher. Each local chapter creates its own unique program of activities (POA) to serve and support its learners’ developmental needs. The three-tiered organizational structure’s flexibility supports local agricultural educators as they plan relevant educational experiences for their unique learners (Dewey, 1938; Roberts, 2003). To learn more about the National FFA Organization, its constitution and bylaws, and how local FFA chapters are chartered, please visit the National FFA Organization website https://www.ffa.org.

Competencies Taught through FFA

The National FFA Organization promotes premier leadership, personal growth, and career success. Learners acquire and apply technical knowledge combined with leadership and interpersonal knowledge and skills through FFA activities. Agricultural educators are responsible for organizing learning experiences relevant to the local, regional, state, and national industry needs, which provides learners with technical content. Technical content may be food science, urban agriculture, animal production, agricultural mechanics, or a multitude of other topics relevant to food, agriculture, and natural resources. Leadership and interpersonal competencies are integrated into the learning and practice.

Examples of leadership and interpersonal competencies include but are not limited to oral and written communication, critical thinking, problem solving, teamwork, personal responsibility, meeting facilitation, conflict management, recording keeping, innovation, creativity, goal setting, collaboration, relationship building, and others. Learners practice technical skills simultaneously with leadership and interpersonal skills just as they occur in real life. For example, students applying for a proficiency award in agriscience research not only demonstrate technical competence on their research topic, but they also demonstrate recording keeping, communication, and other leadership and interpersonal skills.

Students competing in the forestry career development event (CDE) must call upon their technical knowledge about forestry while simultaneously practicing teamwork, communication, time management, and other leadership and interpersonal competencies. Local chapter officers and members apply proper parliamentary procedure to conduct the work of their organization in meetings but also to practice collaboration, meeting facilitation, relationship building, and other leadership and interpersonal skills as the work is carried out in accordance with their program of activities.

FFA Learning Experiences

Membership and Degrees

The National FFA Organization provides a broad structure within which agriculture teachers can plan and organize learning experiences. All FFA experiences begin with learners enrolling in an agricultural education course and securing membership in the FFA organization. Most often, this requires the school to have a chartered local FFA chapter. However, some state associations and local chapters may allow students to join FFA chapters in neighboring school districts if their school does not have an FFA chapter. Although FFA is considered an integral and inseparable component of the agricultural education program, annual membership dues are still required. Membership dues are levied at the national level and may include additional charges from the state association and local chapter.

Currently, there are two ways to become a member. In some chapters, dues are paid for each individual student who wishes to join the organization. Students themselves may pay their dues or the chapter may utilize fundraising or other means of financial assistance to pay dues for students who wish to become FFA members. Other local chapters pay program affiliation fees that provide FFA membership for all learners enrolled in one or more agricultural education courses, based on a progressive fee structure. This allows all students enrolled in agricultural education courses to be FFA members, regardless of their ability or willingness to pay an individual annual membership fee. All membership dues and program affiliation fees are established by a majority vote of eligible voting delegates at each level of the organization: national voting delegates at the National FFA Convention, state voting delegates at the state convention, and eligible members at a regular local chapter meeting.

Membership provides the first and most basic teaching opportunity. FFA members are eligible to progress through five degrees of membership based on individual achievement (FFA, 2021). Each degree of membership advances from the previous as the learner achieves the minimum qualifications and applies for each degree. In order, membership degrees are Discovery, Greenhand, Chapter, State, and American. It should be noted that Discovery degrees are intended for state associations and local chapters that offer membership to middle school students. Teachers can use degrees of membership to organize educational content as learners acquire knowledge through experience. Since each degree builds upon achievements from the previous degree, the learning is naturally situated within the learner’s realm of understanding and linked to each learner’s unique previous experience (Dewey, 1938; Roberts, 2003). Moreover, learners pursue each degree’s qualifications in a context of their choosing, further ensuring that knowledge is built from their personal experiences.

Let’s consider another example.

Sarah is enrolled in an agribusiness course at her high school. She is an active FFA member and, with her teacher’s guidance, has developed an SAE. Last year, as a freshman, she earned the Greenhand degree by successfully meeting the National FFA constitution’s requirements and submitting a written application to her local chapter. One of the requirements was to develop a satisfactory plan for an SAE. Sarah discussed her interests and experiences with her teacher and after conducting research with her teacher’s guidance, she decided she was most interested in beekeeping. Her teacher introduced her to a local beekeeper, who offered Sarah an opportunity to work with him and learn more about his business.

This year, Sarah plans to apply for her Chapter FFA degree. She enrolled in the agribusiness course to learn more about owning and operating her own business. In addition, she works with the local beekeeper a few hours a week, earning a little money and gaining a lot of experience. She attends the local farmer’s market with the beekeeper, where she assists with teaching the public about honeybees. She plans to use the money she earns to purchase her own hive and rent some space from the local beekeeper to keep her hive with his. With her teacher’s help, she has laid out a four-year plan to advance through the degrees of FFA membership, eventually earning her American FFA degree.

Competitive Events and Awards

The National FFA Organization offers a robust program of awards and competitive events that can be implemented at all three levels (local, state, and national). Competitions and awards are available for individuals, teams, and chapters. Competitive events are generally separated into Career Development Events (CDE) and Leadership Development Events (LDE).

As previously stated, the National FFA constitution and bylaws allow for some autonomy at the state and local levels to develop and offer competitive events and awards that reflect both the industry’s and learners’ unique needs. A current list of national competitive events and awards can be found on the National FFA Organization website, www.ffa.org. Teachers should contact their state association for a current list of state competitive events and awards. Some examples of unique events offered by state associations include the Quartet contest in Alabama, citrus evaluation in Florida, tractor troubleshooting in Vermont, milk quality evaluation in North Carolina, meat evaluation in Pennsylvania, and cotton judging in Texas.

Competitive events provide incentive and require students to combine technical knowledge and skill with leadership and interpersonal knowledge and skill. Some competitions require a team, while others are for individuals. Competitive events expand learners’ social environment as FFA members may receive coaching from community members who are industry experts and travel to various locations to compete and interact with FFA members and advisers from other chapters. Furthermore, competitive events are directly related to classroom and laboratory instruction, thus providing a natural extension of learning through educative experiences in a social environment different from the traditional classroom.

A good example might be as follows:

A group of students who are enrolled in a food science course compete in the food science and technology CDE. Students learn technical content from their agriscience teacher in their course, meet once a week with a community member who is familiar with the event and works as a food safety specialist at the local chicken processing plant, and then travel to FFA competitions around the state where they compete against and interact with students from other FFA chapters.

Awards also incentivize learners to set and achieve developmental goals. In addition, they provide structure for teachers to organize learners’ educational experiences. Like degrees of membership, awards are often earned by accomplishing a complementary set of tasks that draw on technical knowledge and skills as well as on leadership and interpersonal knowledge and skills. This is true for individual, team, and chapter awards. Some examples of awards include National Chapter Awards (awarded at the state and national levels), Agricultural Proficiency Awards (awarded at the local, state, and national levels), and Star Awards (awarded at the local, state, and national levels). Competitive events and awards can be unique and nontraditional educative experiences, but the teacher must plan diligently to achieve the desired student learning outcomes.

Conduct of chapter meetings is a common CDE offered by state associations and the national organization. The contest requires a team of students to conduct a meeting completing a specific list of tasks, according to prescribed parliamentary procedure. Conducting a meeting using parliamentary procedure is a valuable skill that requires a combination of technical knowledge and interpersonal skills to successfully accomplish the group’s business. A teacher can utilize the conduct of chapter meetings contest to teach students correct parliamentary procedure through application and practice (experience). Learners apply their knowledge not only in the contest but also as FFA members directing the business of their local chapter and ultimately in adulthood as they engage in professional or civic organizations.

Events and Conferences

Events and conferences offer unique educational experiences. The National FFA Organization hosts numerous events and conferences. Some conferences are hosted by state associations with support from the National Organization. The National FFA Organization website and your state associations keep a current list of events and conferences offered. Examples include the National FFA Convention, Washington Leadership Conference (WLC), state or regional greenhand leadership camps, and many others.

Conferences offer another social environment in which teachers can organize student learning. FFA conferences are frequently focused on leadership and interpersonal skill development, though some may also focus on specific technical content. Learners return from conference experiences prepared with knowledge and skills to operate their local chapter. In this way, learners’ knowledge and skills continue to build through personal and relevant experiences. For example, if a local chapter officer engaged in team-building workshops at a conference, they can apply that knowledge and skill to facilitate team-building activities that build cohesion and camaraderie among their chapter members. Alternatively, local FFA members may attend a conference where they learn about civil discourse and building consensus in group decision-making. They apply that knowledge to productively contribute to the development of their chapter’s program of activities (POA). FFA conferences may last a few hours or several days. Each conference has specific learning outcomes for participants and incorporates a variety of activities and experiences to help learners achieve those outcomes. With careful planning, teachers can organize educational experiences that extend all learners’ growth and development beyond the conference or event.

Diversity and Inclusion Efforts and Opportunities in FFA

FFA is intracurricular, which means it should be as accessible as its complementary components of the three-circle model (Classroom and Laboratory, Supervised Agricultural Experience, FFA). The teacher is responsible for ensuring efforts are made toward diversity and inclusion. FFA programs and activities can include all learners. The National FFA Organization continues to pursue diversity, inclusion, and equity throughout the organization as demonstrated through the National FFA Value Statements ratified by the delegates at the 2021 National FFA Convention.

Ratified FFA Value Statements

- We respect and embrace every individual’s culture and experiences.

- We welcome every individual’s contribution to advance our communities and the industry of agriculture.

- We cultivate an environment that allows every individual to recognize and explore their differences.

- We create leadership opportunities for every individual to enhance their personal and professional endeavors.

Additional efforts and ideas to increase accessibility are outlined in this section.

Affiliate program fees, paid by the chapter instead of by individuals, can reduce socioeconomic barriers to participation in FFA learning activities. Students’ freedom to select from official dress options can reduce potential gender and cultural barriers. The National FFA Organization provides CDE and LDE resources in Spanish and offers a Spanish version of the Creed Speaking contest. Local chapters and agricultural classrooms should welcome and provide opportunities for all learners and strive to represent the demographics of the local school system and community.

FFA’s history of supporting diversity and inclusion has evolved over the years from membership to leaders to policies and practices. The first female members were admitted in 1969. The first African American national leader was elected in 1994, and the first Latino national leader elected in 2002. In 2017, the first African American female national president was elected. The 2019 National Convention featured the first opening ceremonies ever conducted in Spanish. The National FFA Organization provides educator resources for teachers who wish to incorporate lessons on diversity and inclusion as well. You can find those resources on the National FFA Organization’s website, www.ffa.org.

Teaching with FFA Educational Experiences

Teachers must intentionally plan and organize educational experiences. In SBAE, this includes FFA experiences. As illustrated by the three-circle model, classroom and laboratory instruction, SAE, and FFA are integrated and overlapping. Educational experiences can and should be organized to incorporate all three. Some examples of how teachers can integrate FFA into their teaching are presented below.

Mr. Brown is a SBAE teacher. He begins an instructional unit by requiring students to attend their local school board meeting to observe parliamentary procedure. Students then learn about proper meeting conduct through a series of lessons in class. Students compete in the conduct of chapter meeting CDE, gaining additional practice. Finally, students apply appropriate parliamentary procedure as they engage in the work of their local FFA chapter. Mr. Brown’s approach illustrates one way teachers can use FFA to extend and deepen students’ learning.

Josh has been enrolled in agricultural education courses since he was in middle school, where he earned the Discovery degree. One requirement of the Discovery degree was researching agricultural careers. Josh took a particular interest in landscape and horticulture careers. In high school, Josh enrolled in the plant science course, where he continued to learn more about horticulture. Josh earned his Greenhand degree and developed a plan for an SAE that continued to expand his interest in plants, horticulture, and landscape. He earned a spot on his chapter’s plant identification CDE team and has started practicing for the floral CDE. Josh has a placement SAE delivering floral arrangements for the local flower shop. He enjoys interacting with customers in the shop and teaching them about the different plants and flowers. Josh’s teacher has also asked him to comanage the school greenhouse and he serves on the annual plant sale committee for his local FFA chapter. Josh’s SBAE experience exemplifies fully integrated classroom and laboratory instruction, SAE, and FFA.

The adviser of the Newberry FFA Chapter utilizes the POA to plan, organize and facilitate student learning experiences through FFA. Each year, the chapter officers lead members in developing a POA. The POA defines chapter goals and outlines plans to meet those goals. It is organized into three divisions: Growing Leaders, Building Communities, and Strengthening Agriculture. Each division contains five quality standards which allow for student committees to plan, prepare, and deliver activities in each area. Newberry FFA’s POA is informed by community and local industry needs, considers the planned classroom and laboratory instruction, and addresses students’ interests and needs. Students learn and practice a multitude of skills while developing the POA and while completing the planned activities throughout the year. Newberry FFA’s approach to developing and carrying out a program of activities demonstrates how FFA, as a crucial component of the three-circle model, provides experiential education in SBAE programs. (For more information on Program of Activities, please see the resource guide on the National FFA website, www.ffa.org.)

Summary

- Explain FFA as an intracurricular component of the complete agricultural education model.

- Describe the structure and components of FFA.

- Identify competencies taught through FFA activities.

- Illustrate efforts and opportunities for diversity and inclusion in FFA.

- Utilize FFA programs and activities as experiential learning opportunities for learners.

This chapter has described how FFA is an intracurricular component of a complete school-based agricultural education program thanks to its federal charter. FFA provides a three-tier structure and a multitude of activities and opportunities that support agriculture educators as they organize educative experiences for learners. These experiences allow learners to build upon their current knowledge and experience in a variety of social contexts, foster valuable adult-youth relationships, and challenge learners to integrate technical knowledge and skills with leadership and interpersonal knowledge and skills. Teachers must be intentional in selecting and organizing experiences that compliment and extend learning from the other two components of the three-circle model, classroom and laboratory instruction and SAE. In addition, teachers must continue to champion diversity and inclusion efforts, making SBAE accessible to all learners. Ultimately, when FFA is fully integrated with classroom/laboratory instruction and SAE, students received a robust and complete agricultural education that simultaneously supports the food, agriculture, and natural resources industry.

Learning Confirmation

- Draw the three-circle model of agricultural education. Identify learning activities that exist in the center of the diagram where all three circles overlap as well as activities that exist where two of the three components overlap.

- Outline an example program of activities. Explain how the FFA activities included support, extend, and enhance learning in the classroom and laboratory.

- Identify a Career Development Event of your choice. List personal development and leadership competencies learners will practice simultaneously with the required technical content knowledge.

Applying the Content

- Identify three Career Development Events that can be used in a local context to prepare FFA members for future careers in their community.

- Identify three Leadership Development Events that can be used in a local context to teach leadership skills that FFA members can use in their community.

- Prepare an introductory lesson to teach about FFA opportunities to new agricultural education students.

Reflective Questions

- What challenges or barriers might teachers have to overcome to fully integrate FFA in their teaching?

- How can agriculture teachers involve stakeholders, especially those in the community, to strengthen the connection between the classroom and laboratory, SAE, and FFA learning?

- FFA offers a broad range of activities for teachers to incorporate. How can teachers identify the most effective and appropriate learning experiences for learners?

Glossary of Terms

- experiential learning: The process of learning by doing that involve hands-on experiences and reflection by learners

- Supervised Agricultural Experience (SAE): a planned and supervised program of experience-based learning activities that extend school-based instruction and enhance knowledge, skills, and awareness in agriculture and natural resources

- school-based agricultural education (SBAE): Systematic program of instruction in agriculture, food, and natural resources for K-12 students within a school program.

- National FFA Organization (FFA): A youth leadership organization that strives to make a positive difference in the lives of young people by developing their potential for premier leadership, personal growth, and career success through agriculture education

- proficiency awards: a program to recognize FFA members for their performance in supervised agricultural experience (SAE) programs; students can be recognized at the local, state, and national level

- Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory: Theory that concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization and active experimentation form a four-stage process (or cycle) transformed into effective learning

- Career Development Events (CDE): Events sponsored through FFA where students compete in career areas to demonstrate their skill and expertise

- Leadership Development Events (LDE): Events sponsored through FFA where students compete in leadership areas such as public speaking and parliamentary procedure to demonstrate their skill and expertise

- Program of Activities (POA): A plan for executing events and activities typically developed by student leaders with guidance by the agriculture teacher

- three-circle model: A conceptual model for the total agricultural education program including classroom/laboratory instruction, FFA, and supervised agriculture experience

Resources

The National FFA Organization website, www.ffa.org, houses a plethora of resources for teachers, including resources for the classroom/laboratory, information on competitive events, awards, conferences, and other learning experiences, and advice for agricultural educators from agricultural educators.

FFA New Horizons is a magazine published quarterly by the National FFA Organization. An archive of issues can be found at https://archives.iupui.edu/handle/2450/2473 courtesy of Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis University Library Ruth Lilly Special Collections & Archives.

The Agricultural Education Magazine, https://www.naae.org/profdevelopment/magazine/, is a professional journal published by the National Association of Agricultural Educators and provides an outlet for news, research, and other content appropriate for and pertinent to agricultural educators.

The Journal of Agricultural Education, published by the American Association for Agricultural Education can be accessed at https://jae-online.org/index.php/jae. A rigorous peer-reviewed publication outlet for agricultural education faculty at higher education institutions, it is a source of science-based recommendations for agricultural educators. Some relevant articles include:

- Martin, M. J., & Kitchel, T. (2015). Advising an urban FFA chapter: A narrative of two urban FFA advisors. Journal of Agricultural Education, 56(3), 162–177. http://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2015.03162

- Rose, C., Stephens, C. A., Stripling, C., Cross, T., Sanok, D. E., & Brawner, S. (2016). The benefits of FFA membership as part of agricultural education. Journal of Agricultural Education, 57(2), 33–45. http://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2016.02033

- Shellhouse, J. A., Suarez, C. E., Benge, M., & Bunch, J. C. (2021). Mentoring mentality: Understanding the mentorship experiences of FFA officers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 62(1), 29–46. http://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2021.01029

- Wakefield, D., & Talbert, B. A. (2003). A historical narrative on the impact of the New Farmers of America (NFA) on selected past members. Journal of Agricultural Education, 44(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2003.01095

The Friday Footnote, https://footnote.wordpress.ncsu.edu/, is a weekly blog written by Dr. Gary Moore, Professor Emeritus at North Carolina State University. His writing focuses on the history of agricultural education and rural America, including FFA, and includes a plethora of references to additional resources.

About FFA: https://www.ffa.org/about/

Agricultural Education Inside the Agrobox: https://www.ffa.org/ffa-new-horizons/agricultural-education-inside-the-agrobox/

Owl Chat: Educational Resources from National FFA: https://www.ffa.org/ffa/owl-chat-educational-resources-from-national-ffa/

SAE for All: Evolving the Essentials: https://saeforall.org/immersion-sae/

Town Hall Discusses Agricultural Education for All: https://www.ffa.org/agricultural-education-for-all/town-hall-to-discuss-agricultural-education-for-all/

Figure Descriptions

Figure 10.1: Three circle Venn diagram. Circle 1 represents classroom/laboratory. This is contextual, inquiry-based instruction and learning through an interactive classroom and laboratory. Circle 2 represents FFA. This is premier leadership, personal growth, and career success through engagement in FFA, PAS, or NYFEA programs and activities. Circle 3 represents SAE. This is experiential, service, and/or work-based learning through the implementation of a supervised agricultural experience program. All three circles meet in the center to represent school-based agricultural education. Jump to figure 10.1.

Figure 10.2: Circular diagram. Concrete experience points to observations and reflections points to formation of abstract concepts and generalizations points to testing implications of concepts in new situations. Points back to concrete experience. Jump to figure 10.2.

Figure References

Figure 10.1: Three Circle Model. Kindred Grey. 2023. Adapted under fair use from FFA, “The Three-Component Model.” https://www.ffa.org/agricultural-education/

Figure 10.2: Kolb’s experiential learning model diagram. Kindred Grey. 2023. Adapted under fair use from David A. Kolb, “Experiential Learning: Experience As The Source Of Learning And Development,” 1984. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235701029_Experiential_Learning_Experience_As_The_Source_Of_Learning_And_Development

References

Baker, M. A., Robinson, S., & Kolb, D. A. (2012). Aligning Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory with a comprehensive agricultural education model. Journal of Agricultural Education, 53(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2012.04001

Committee on Agricultural Education in Secondary Schools. (1988). Understanding agriculture: New directions for education. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/766

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Simon & Schuster.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Roberts, T. G. (2003). An interpretation of Dewey’s experiential learning theory. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED481922.pdf

The National FFA Organization. (2021). About FFA. https://www.ffa.org/about/

The National FFA Organization. (2019a, March 13). FFA Federal Charter. https://ffa.app.box.com/s/kpbbzar0hjej0i8odx9gg065vfow8boa

The National FFA Organization. (2019b, November 11). National FFA Constitution. https://ffa.app.box.com/s/m5882jqjl7cxhn5kr971xl57nib4r5le

Future Farmers of America Federal Charter, 36 U.S.C. §709. (2019). https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title36/subtitle2/partB/chapter709&edition=prelim