12. Formulate Multinational Strategy

After engaging with this chapter, you will understand and be able to apply the following concepts.

- The motivations for going global

- The risks of going global

- Theories of multinational business

- The CAGE distance framework

- The integration responsiveness framework

- Methods of entry available to firms that seek to compete in international markets

- Why multinational strategy is important to business graduates

You will be equipped to analyze a firm’s

- Opportunities and threats in different global markets using the CAGE distance framework analysis instrument

- Corporate multinational strategy using the integration-responsiveness framework

12.1 Introduction

You have learned about the innovation, sustainability and ethics, and technology strategies embedded in business-level strategy at the strategic business unit level of a firm. Successful companies address each of these areas.

In this chapter, you learn about the next embedded strategy: multinational strategy. This involves a review of the history of global commerce. You learn the motivations and risks associated with choosing a multinational strategy. Next you learn key theories of multinational business. Then you learn a framework for analyzing the attractiveness of foreign markets, the CAGE distance framework, which assesses foreign markets along four dimensions: cultural, administrative, geographical, and economic. The chapter explains how to use the CAGE distance framework analysis instrument to analyze the attractiveness of proposed foreign markets.

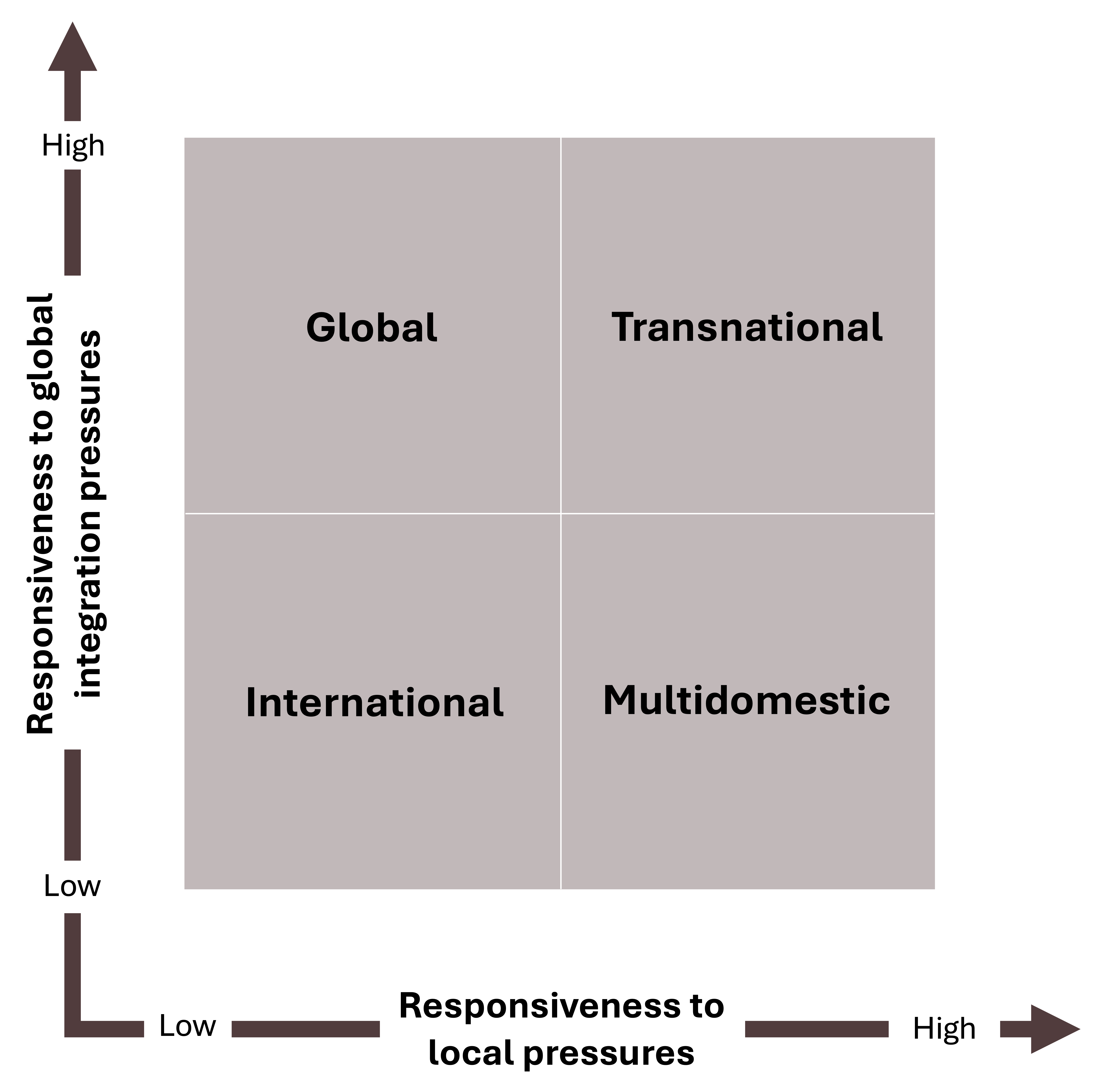

Next you learn a framework for types of multinational strategy, the integration-responsiveness framework. This framework analyzes multinational strategy along two dimensions, whether the strategy is responsive to global integration pressures and whether the strategy is responsive to local pressures. An international strategy combines a low responsiveness to global integration pressures with a low responsiveness to local preferences. A multidomestic strategy combines a low responsiveness to global integration pressures with a high responsiveness to local preferences. A global strategy combines a high responsiveness to global integration pressures with a low responsiveness to local preferences. A transnational strategy combines a high responsiveness to global integration pressures with a high responsiveness to local pressures.

Then you learn about a firm’s choices when entering foreign markets, as well as issues and strategies related to exporting, licensing and franchising, joint ventures, strategic alliances, wholly owned subsidiaries, and foreign direct investment. Finally, you learn how to analyze multinational strategy when you conduct a case analysis.

12.2 Multinational Strategy

Like all strategy formulation, multinational strategy answers the question “Where are we going?” Multinational strategy addresses where a firm is going as it relates specifically to its commerce in foreign markets.

Like innovation, sustainability and ethics, and technology strategy, multinational strategy is formulated at the strategic business unit level of a company and embedded in business-level strategy. It addresses how a firm is going to win or compete in its chosen markets and market segments.

A multinational corporation (MNC) is a firm that has operations in more than one country. Not all companies compete internationally. Multinational corporations formulate multinational strategy. Mutinational strategy focuses on the ways multinational corporations compete in global markets.

Like all strategy, multinational strategy focuses on an outside-in perspective. Companies carefully monitor their external environments, analyze trends, and formulate strategies that are forward-looking. Robust multinational strategy considers the volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous nature of the firm’s external environment.

Multinational strategy is a critical component of a company’s strategy. Multinational strategy focuses on expanding operations beyond domestic markets to drive profitable growth and manage risks effectively. This approach involves strategic decision-making about how best to enter and compete in foreign markets, whether and to what degree to adapt products or services to local consumer preferences and cost pressures, and how to manage multinational risks and secure competitive advantage on a global scale. By pursuing multinational strategy, companies can tap into larger consumer bases; distribute risk across diverse industries, markets, market segments, and businesses; enhance operational efficiencies; and leverage global resources, capabilities, and core competencies. As part of a broader business-level strategy, multinational expansion enables firms to achieve scale, optimize resource allocation, and capitalize on new growth opportunities, all while bolstering their resilience in an increasingly interconnected marketplace.

Application

- Research three multinational corporations in three different market sectors.

- Describe their product lines.

Multinational strategy addresses where a firm is going as it relates specifically to its commerce in foreign markets. Like innovation, sustainability and ethics, and technology strategy, multinational strategy is another strategy focus that is formulated at the strategic business unit level of a company and embedded in business-level strategy. A multinational corporation (MNC) is a firm that has operations in more than one country. Not all companies compete internationally. Multinational corporations formulate multinational strategy. Mutinational strategy focuses on the ways multinational corporations compete in global markets.

12.3 The History of Global Commerce

The evolution of multinational strategy has followed significant historical events that shaped global commerce. The Silk Road facilitated early trade between Asia and Europe. Prior to European contact, many indigenous nations, such as First Nations in the Americas, had elaborate federations and complex trade agreements (Blackhawk, 2023). Colonialization has rightly come under serious critical scrutiny for its impacts on indigenous populations. European colonial expansions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries laid the groundwork for modern multinational trade. In the twentieth century, multilateral institutions like the World Trade Organization (WTO) and economic blocs such as the European Union played pivotal roles in reducing trade barriers and promoting cross-border trade. Trade agreements, such as the North America Trade Agreement, support trade between countries, while trade tariffs, such as those between the U.S. and China, can discourage or limit commerce across borders.

Today, technological advancements, improved communication, and the rise of free trade agreements have created a more interconnected global economy, offering companies diverse opportunities for strategic multinational expansion and the ability for some companies to be “born global” at their founding. Globalization provides companies with unprecedented strategic opportunities, including access to new industries, markets, market segments, and businesses. Multinational firms gain economies of scale and the advantage of being able to source talent globally.

However, globalization also poses challenges that require careful planning. Multinational businesses must manage cultural differences, mitigate political risks, and handle the complexities of global supply chains. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the vulnerabilities of international supply chains, but it also underscored the importance of agility and innovation in multinational strategy, which must be able to adapt quickly to changing circumstances.

One example of successful international strategy is the German mobility startup Tier Mobility. Originally focused on micromobility solutions in its home market, Tier expanded its operations across Europe, capitalizing on the increasing demand for sustainable urban transport solutions. By 2023, Tier had expanded into new cities such as Oslo and Rome, offering electric scooters and bicycles. Tier’s multinational strategy involved building strong relationships with local municipalities and tailoring its offerings to fit specific urban needs, including adapting to different regulatory environments. This tailored approach helped Tier successfully navigate the complexities of international expansion, grow its brand, and enhance city partnerships for sustainable transportation solutions.

Another recent example is the case of Swedish oat milk producer Oatly. Oatly strategically expanded from Europe into North America, recognizing a shift in consumer preferences toward plant-based dairy alternatives. The company’s multinational strategy is built on its ability to convey a clear message about sustainability, climate change, and healthy lifestyle choices. By focusing on these attributes and partnering with notable coffee chains such as Starbucks, Oatly expanded its market presence in the United States and Canada. By 2023, Oatly had not only increased its market share but had also successfully navigated distribution challenges by setting up local manufacturing facilities and minimizing the logistical issues and tariffs that often arise with international shipments.

These examples illustrate the importance of understanding local market dynamics, aligning products with consumer trends, and forming strategic partnerships as part of an effective multinational strategy. Success lies in being agile and building robust relationships, which are key factors for any company aiming to thrive on the international stage.

The evolution of multinational strategy has followed significant historical events that shaped global commerce, beginning with the Silk Road that facilitated early trade between Asia and Europe and the elaborate federations and complex trade agreements of many indigenous nations prior to European contact. Today’s trade agreements support trade between countries, and trade tariffs can discourage or limit commerce across borders.

Bibliography

Blackhawk, N. (2023). The rediscovery of America, native peoples and the unmaking of U.S. history. Yale University Press.

Buckley, P. J. (2009). Business history and international business. Business History, 51(3), 307–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790902871560

Dormanesh, A., Majmundar, A., & Allem, J.-P. (2020). Follow-up investigation on the promotional practices of electric scooter companies: Content analysis of posts on Instagram and Twitter. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(1), e16833–e16833. https://doi.org/10.2196/16833

Fechter, M. (2023). Miami-based Bird Global, which sells and rents electric bicycles and scooters, bought out Skinny Labs from Berlin-based TIER Mobility for $19 million. Florida Trend, 66(9), 41.

Jones, G. (2004). Multinationals and global capitalism: From the nineteenth to the twenty first century (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199272093.001.0001

McCarthy, D. M. P. (1994). International business history: A contextual and case approach. Praeger.

Oatly shares fall 20% after “quality issue” warning and delivery delays; Swedish oat milk producer blames “temporary headwinds” in production and distribution for increased losses. (2021, November 15). The Guardian (London).

Oat-milk brand Oatly chooses Philly site for North American product-development labs. (2020, July 11). The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Shieber, J. (2020). Blackstone’s growth investors lead a $200 million investment into Oatly, the oat-milk juggernaut. TechCrunch.

TIER Mobility raises U.S. $60 million in its Series B led by Mubadala Capital and Goodwater Capital. (2019). Health & Medicine Week, pp. 723.

Durbin, D. (2021). Warm welcome for oat milk maker Oatly in Wall Street debut. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/europe-lifestyle-health-business-f5bf285bf70e1bf73d050656d110aa7e

12.4 Motivations and Risks when Choosing a Multinational Strategy

Companies that choose a multinational strategy share common motivations and also share similar risks.

Motivations for Choosing a Multinational Strategy

Companies pursuing international expansion are often driven by multiple motivations, each tied to enhancing competitiveness, increasing profitability, and positioning themselves strategically within the global market. However, going global comes with its share of complexities and challenges. This section delves into both the motivations behind international expansion and the drawbacks companies face when they decide to operate globally.

Market Seeking

One of the foremost motivations for international expansion is market seeking. Companies often look to expand into new geographic areas to find additional customers, especially when their domestic market is either saturated or shows limited growth potential. By tapping into larger or faster-growing international markets, businesses can significantly increase their revenue streams. For instance, French electric vehicle manufacturer Hopium expanded into the North American market in 2023 to capture the growing demand for electric vehicles in the United States, spurred by favorable government policies and shifting consumer preferences toward green technologies. By gaining a foothold in a lucrative and evolving market, companies like Hopium aim to build stronger brands and secure their shares of new revenue opportunities.

An important driver of finding more robust growth opportunities abroad is the emergence of middle classes in developing countries. Strong population growth in developing countries and emerging middle classes provide untapped growth opportunities that haven’t been present in the past, when only a small percentage of the population had enough buying power to purchase consumer products from U.S. global players. For example, in the past, the majority of Indian consumers used bar soap to wash their hair and laundry. Now, hundreds of millions of consumers in India’s emerging middle class have the buying power to buy hair shampoo and laundry detergent, which represents huge market opportunities for companies like the U.S. consumer giant Procter & Gamble or Dutch/British consumer giant Unilever. Emerging countries like China, Brazil, India, and Russia have now become growth engines for U.S. companies, and the former BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China) have now become BRIC+ with the addition of countries like Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates.

Resource Seeking

Another major driver for international expansion is resource seeking, which involves accessing cheaper or higher-quality inputs for production. Businesses, particularly those in manufacturing or industries dependent on natural resources, expand internationally to secure better access to raw materials or labor. Finnish renewable energy company Neste, for example, moved into the Asia-Pacific region in 2022 to secure sustainable feedstocks for renewable diesel production. By situating closer to essential resource bases, Neste aimed to reduce logistical costs and ensure a consistent supply, providing a competitive edge in the renewable energy market.

Efficiency Seeking

Efficiency seeking is also a core motivation for internationalization, where companies expand to improve their operational efficiency and profitability. This typically involves leveraging economies of scale or shifting certain operations to regions where costs are lower.

Asset Seeking

Strategic asset seeking is another important motivator, driving companies to pursue international expansion to acquire knowledge, technology, or unique resources, capabilities, and core competencies that are critical for growth. This often involves forming partnerships or acquiring firms with advanced technological assets or market expertise. South Korean conglomerate SK Group, for example, expanded into the U.S. market by acquiring stakes in American battery technology firms, positioning itself favorably within the growing electric vehicle industry. By accessing cutting-edge battery technology through strategic partnerships, SK Group aimed to secure its place at the forefront of a rapidly changing market.

While international expansion offers opportunities for market growth, access to resources, operational efficiencies, and strategic assets, it also involves significant risks that require careful planning and strategic management to avoid and mitigate.

Risks of Choosing a Multinational Strategy

Companies must weigh the potential benefits of choosing a multinational strategy against the potential challenges, such as complex regulations, economic instability, supply chain vulnerabilities, cultural differences, and the need for brand consistency. A successful multinational strategy involves not only leveraging the motivations that drive expansion but also anticipating the challenges that come with entering diverse global markets.

Expanding internationally brings a variety of risks that companies must understand and mitigate to ensure success. While international markets offer opportunities for growth, cost savings, and strategic positioning, they also expose businesses to diverse and often unpredictable risks. Some of the risks that accompany international business operations include political risk, economic risk, operational risk, cultural risk, legal and regulatory risk, competitive risk, financial risk, and reputational risks.

Political Risk

One of the most prominent international risks is political risk, which arises from the uncertainty of government actions in foreign countries. Political risk can include sudden changes in government policies, the nationalization of industries, civil unrest, or unexpected changes in trade regulations. These factors can significantly affect a company’s ability to operate effectively. For instance, in 2022, dozens of Western companies faced difficulties in Russia due to increased government scrutiny and economic sanctions, leading some to halt operations or exit the market entirely. Such political dynamics can disrupt operations and create unexpected costs, making it critical for companies to assess the political climate before investing heavily in a foreign market.

Economic Risk

Economic risk is another significant consideration for companies operating internationally. Exchange rate fluctuations can have a major impact on profitability, especially when earnings from foreign operations need to be repatriated. Sudden currency devaluations can erode profit margins, while currency appreciation in a company’s home country can make its exports less competitive. The recent volatility in the Turkish lira, for instance, has had a profound impact on foreign businesses operating in Türkiye, leading to increased costs and challenges in managing price stability. Additionally, inflation rates, interest rates, and overall economic stability in the target market can affect consumer purchasing power and the overall business environment.

Operational Risk

Operational risk also plays a significant role in international expansion. These risks include logistical challenges, supply chain vulnerabilities, and difficulties in maintaining consistent quality standards across borders. Global supply chains are vulnerable to various disruptions, such as natural disasters, strikes, or changes in trade agreements. The COVID-19 pandemic exemplified the impact of such disruptions, with companies experiencing significant delays and increased costs as global supply chains were interrupted. Companies need to build resilient supply chains by diversifying suppliers and creating contingency plans to mitigate these operational risks. Firms must also acknowledge that managing and coordinating international businesses in various countries increases costs and the complexity of a business.

Cultural Risk

Cultural risk is another aspect that can directly affect the success of an international strategy. Differences in consumer behavior, language, business practices, and societal values require careful consideration. Failure to understand these cultural dynamics can lead to marketing blunders, poor customer engagement, or even reputational damage. For instance, some fast-food companies have faced backlash in certain regions when their advertising or product offerings did not align with local cultural norms and expectations, such as promoting beef products in predominantly vegetarian countries or using advertising themes that conflict with local values. Another example is Walmart’s failed market entry into the German retail market. Walmart almost lost a billion dollars as a result of not fully understanding very different German consumer shopping habits. These missteps highlight the importance of tailoring products and messaging to resonate with diverse cultural contexts, ensuring a more successful international strategy. Successfully mitigating cultural risks requires in-depth market research, cultural sensitivity training, and often local talent who can provide valuable insights into consumer preferences and behaviors.

Legal and Regulatory Risk

Legal and regulatory risk also poses a challenge when operating in multiple jurisdictions. Each country has its own set of laws and regulations related to labor, environmental standards, taxation, and data privacy, which can be complex and costly to navigate. Companies need to comply with these laws and regulations to avoid fines, legal disputes, and reputational harm. For instance, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has strict requirements regarding the collection, use, and storage of consumer data, impacting how companies do business in Europe. Legal compliance is a matter of not only adhering to laws but also ensuring that operations align with evolving regulatory landscapes across different markets. Another risk is the difficulty of protecting intellectual property in some countries, especially when the company enters a partnership, like a joint venture, with local partners. Lastly, tariffs and other trade barriers may change, leading to a loss of profit and market access.

Competitive Risk

Competitive risk arises from the uncertainty of entering new markets where existing players may have a substantial advantage. Local competitors often have a deeper understanding of the market, established customer relationships, and more agile responses to changes in the local environment. This can create challenges for new entrants who are still learning to navigate the complexities of a foreign market. For instance, many Western e-commerce companies have struggled to compete in China, where local giants like Alibaba and JD.com dominate the market through their local brand image, extensive logistics networks, and consumer loyalty programs.

Financial Risk

Financial risk is another crucial factor to consider, especially when dealing with markets that have limited access to financing or higher capital costs. Businesses may face challenges in accessing affordable funding to support their international operations, or they may encounter higher interest rates, making investments more costly. Moreover, inconsistent cash flows due to delayed payments from international customers can pose liquidity challenges. Companies expanding into emerging markets must particularly assess the financial stability of the market and the availability of credit to ensure they can effectively fund their operations.

Reputational Risk

Lastly, reputational risk can arise from operating in multiple regions, where different standards and expectations may lead to perceptions of unfair practices. International businesses are increasingly scrutinized for their impact on the environment, working conditions, and the ethics of their business practices. A misstep in any of these areas can lead to significant backlash and harm to a company’s global reputation. For example, clothing brands have faced criticism for poor working conditions in overseas factories, leading to protests, boycotts, and long-term damage to their brand images. As a response to this risk, many companies implement robust environmental, social, and governance strategies that are covered in greater detail in section 10.7.

The risks of operating internationally are interrelated. For example, Nestle has faced economic, cultural, and reputational risks from claims of selling substandard products in low-income countries like India due to rising costs in their supply chain. Nestle has also been slow to respond to consumer preferences for more sustainable packaging. They are now addressing their packaging and receiving a positive consumer response.

Application

- Consider one of the three multinational corporations you researched above.

- Discuss how market seeking, resource seeking, efficiency seeking, and asset seeking may have been motivators for the MNC to enter global markets.

- Describe the ways political, economic, operational, cultural, legal and regulatory, competitive, financial, and reputational risks may have been affected the MNC when entering global markets.

Bibliography

Alterra. (2024). Alterra, Neste and Technip Energies collaborate to offer standardized solution to build chemical recycling plants. PR Newswire.

Baker, K. (2012). Not lovin’ it. (McDonald’s vegetarian restaurants in India). Newsweek, 160(12), 8.

Beckmann, J., & Czudaj, R. L. (2023). The role of expectations for currency crisis dynamics – The case of the Turkish lira. Journal of Forecasting, 42(3), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/for.2940

FMCG demand sluggish in urban India on account of food inflation, commodity costs: Nestle chairman. (2024, October 23). The Economic Times.

Hansen, Z. (2024, May 24). Feds chip in $75M for semiconductor plant: SK Group’s $600M facility will create jobs for 410 workers. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Hopium concretizes its technological lead and files 10 patents for the Hopium Machina. (2022, July 19). PR Newswire.

Hopium partners with Bridgestone to develop bespoke tyres for hydrogen-powered Hopium Machina. (2022, May 12). PR Newswire.

Hopium chooses Normandy for its first industrial site. (2022, September 23). PR Newswire.

Khan, S. (2020). Walmart’s failed entry into Germany: Were cultural gaffes to blame? SAGE Publications: SAGE Business Cases Originals.

Nestle conducts recycling trial converting liquefied tires into high-quality products. (2024, April 24). Waste360.

Nestle’s crude oil refinery in Finland to be gradually transformed into a renewables and circular solutions refining hub. (2023, December 20). PR Newswire.

Nestle, PepsiCo sell substandard products in low-income countries like India, claims report. (2024, November 10). The Hindustan Times.

Nestle cuts sales targets after backlash against price rises (2024, October 17).The Times (London, England).

Nowinska, A., & Roslyng Olesen, T. (2025). Inter-state war dynamics and investment: Insights from the Russia-Ukraine war. Journal of Business Research, 186, 114911–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114911

Otar, E., Salikzhanov, R., Akhmetova, A., Issakhanova, A., & Mukhambetova, K. (2024). Former Soviet Union middle class: How entrepreneurs are shaping a new stratum and pattern of socio-economic behavior. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-023-00356-2

SK Group named to TIME’s list of 100 Most Influential Companies of 2023. (2023, June 21). PR Newswire.

South Korea’s SK Group to enhance cooperation with Taiwan’s TSMC. (2024, June 7). Taiwan News (Taipei, Taiwan).

Vegetarians have beef with McDonald’s fries. (2001). The Food Institute Report.

Wood, Z. (2024, October 9). Plastic tub gets the snub as Nestlé tests paper container for Quality Street. The Guardian (London).

12.5 Theories of Multinational Business

Theories exploring multinational business provide essential insights into why companies expand across borders, how they select foreign markets, and the strategies they employ for success. These theories help shape the decisions that businesses make as they navigate the complexities of international markets.

Comparative Advantage Theory

Comparative advantage theory (Ricardo, 2004a; Ricardo, 2004b) is one of the oldest and most fundamental theories that explains international trade and business. The theory posits that countries should specialize in the production of goods where they have a lower opportunity cost relative to other nations. This specialization allows countries to benefit from trade by producing what they make most efficiently and trading for what they are less efficient at making. This theory has formed the basis of modern trade policies, explaining why nations and businesses trade in goods and services that maximize their efficiency and productivity. For companies, understanding comparative advantage is crucial when deciding which products or services to produce domestically and which to outsource or import, thereby allowing them to optimize costs and competitiveness. For example, Brazil specializes in coffee due to its climate and the U.S. in machinery due to its advanced technologies. By trading, both benefit in terms of efficiency and cost savings.

OLI Paradigm

The OLI paradigm, also known as the eclectic paradigm (Dunning, 1977), is a comprehensive framework that explains why firms choose to engage in foreign direct investment (FDI) rather than licensing or exporting. OLI stands for ownership, location, and internalization. Ownership advantages refer to unique resources, capabilities, and core competencies that a company possesses, such as technology, brand reputation, or proprietary knowledge, which give it a competitive edge in foreign markets. A firm’s resources, capabilities, and core competencies are analyzed using a VRIO framework, a tool that helps evaluate the “ownership” element of the OLI paradigm. Location advantages pertain to the attractiveness of a foreign market, which may include lower labor costs, favorable regulations, or access to natural resources. Internalization advantages focus on the benefits of maintaining control over operations rather than licensing out technology or the brand. The OLI paradigm thus offers a holistic perspective on why firms decide to establish a physical presence in foreign markets, helping guide decisions on selecting the most appropriate multinational strategy.

Uppsala Model

The Uppsala model of internationalization (Johanson & Vahlne, 2017) provides a gradual, staged approach to multinational expansion. Developed by Swedish researchers, this model suggests that companies begin by entering markets that are culturally and geographically close to their home countries, thereby reducing the uncertainties and risks associated with foreign markets. As firms gain experience and learn from their initial ventures, they expand into markets that are more distant and dissimilar. The Uppsala model emphasizes learning and experiential knowledge, suggesting that firms develop their multinational strategy incrementally, based on the level of knowledge they accumulate over time. It explains the cautious approach often seen in international business, where companies prefer to move step-by-step, increasing their market commitment progressively as they become more confident in their understanding of foreign environments. The CAGE framework discussed in section 12.6 is a useful tool that assesses the cultural (C) and geographical (G) distance between the home country and target foreign markets; it also assesses the administrative (A) and the economic (E) distance.

Porter’s Diamond Model of National Competitive Advantage

Porter’s Diamond Model of National Competitive Advantage (O’Connell, Clancy, & van Egeraat, 1999; Porter, 1991; van den Bosch, van Prooijen, & Porter, 1992) provides an explanation for why certain industries within specific countries are more internationally competitive than others. Michael Porter identified four key factors that provide a competitive advantage for one national economy or business over another. These factors interact to create favorable environments that support the development of competitive industries in international markets. These same factors also influence whether a firm chooses a cost leadership or differentiation business-level strategy. This demonstrates the interconnectedness of business-level strategies and the strategies embedded into them.

The focus of Porter’s Diamond Model is on the industry. The ability of the firms in an industry to be successful in global business is shaped by four factors: (1) factors of production, (2) consumer demand, (3) strategy, structure, and rivalry, and (4) related and supporting industries.

Factors of Production

Factors of production refers to the nature of the resources that firms need to create goods and services in an industry in their home country. Examples include labor, capital markets, and land. Businesses with good access to factors of production are more likely to be successful, and they face challenges when they lack this access. Understanding the factors of production an industry needs and has access to in the home country allows a company to assess the factors of production in foreign markets and make strategic decisions about potential global markets to consider for expansion. For example, India has a large, educated workforce with a high level of English proficiency. When a company understands that the industry needs a workforce like that in India, expanding into India may be a smart option.

Factors of production, such as labor, land, capital, and infrastructure, play a critical role in shaping a company’s multinational strategy. The availability and quality of these resources in a target country also influences whether a company pursues a cost leadership or differentiation strategy, which is part of its business-level strategy. Determining a firm’s strategic market position is based on the characteristics of the target market and market segments. For example, if a country offers low-cost labor, a multinational strategy that focuses on cost leadership strategy may align with target markets or market segments seeking affordability, as companies may be able to remain profitable while paying locally competitive wages. Conversely, if a country has a highly skilled workforce and advanced infrastructure, companies may choose a multinational strategy that focuses on differentiation strategy to create unique products or services that appeal to consumers willing to pay a premium for innovation and quality. Additionally, access to natural resources, supportive governmental laws, regulations and policies, or efficient logistics networks can influence how companies position themselves to meet specific market demands, shaping their competitive approach in each international setting.

Consumer Demand

Consumer demand refers to the nature of domestic customers. Industries in home countries that have demanding consumers produce higher-quality products domestically and are better positioned to compete internationally. For example, Japanese customers demand high-quality, aesthetically pleasing, and reliable vehicles. Japanese automakers produce automobiles in Japan that meet these high customer demands, and this increases their success in foreign markets. Unlike Japanese customers, French customers of automobiles have low demands, and as a result, the reputation of French automobiles is low, and they do not sell well in foreign markets.

Consumer demand is another critical aspect in determining multinational strategy. Companies must understand the nature of consumer demand in each international market to tailor their offerings effectively. For example, emerging markets with large populations and growing middle-class populations often present opportunities for a multinational strategy that includes a cost leadership strategy focused on affordability. On the other hand, sophisticated and demanding consumers can drive companies to innovate and develop high-quality products, pushing them toward a differentiation strategy. Understanding local demand conditions is essential for companies to align their products and services with consumer expectations and gain competitive edge in international markets.

Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

Together, strategy, structure, and rivalry refer to how challenging it is to survive domestic competition. When an industry in a home country has intense rivalry, competition drives quality up and creates a domestic industry of competing high-quality products. Producing high-quality products domestically increases the likelihood the industry will be successful in international markets.

Strategy, structure, and rivalry also play a crucial role in determining how businesses compete internationally. In highly competitive markets, companies need to develop distinctive strategic approaches to succeed. When entering markets with intense local competition, companies may have to adopt innovative practices or find unique ways to differentiate themselves to appeal to consumers. Conversely, in markets with limited local rivalry, firms might find opportunities to achieve cost leadership more easily due to reduced pressure on price competition. The strategic decisions that firms make regarding market positioning, investments, and value propositions are often influenced by the competitive dynamics of each international market.

Related and Supporting Industries

It is common for an industry to rely on related and supporting industries to make products and services for use in its own business. For example, Italians are known for high quality leather goods. Access to an extensive and high-quality leather production industry is essential to the high-end leather goods industry. Being reliant on an industry with few or low-quality products puts an industry at risk. An extensive supporting industry gives an industry more choices when events influence the supporting industry, and it increases competition within the supporting industry to ensure high-quality goods.

The presence of related and supporting industries also influences a company’s business-level strategy in international contexts. When a country has strong supporting industries, such as suppliers, distributors, or specialized service providers, companies can leverage these relationships to enhance efficiency or product quality. This interconnectedness often results in more innovation and efficiency, providing companies with competitive advantages. For example, the automotive industry in Germany benefits significantly from a strong network of supporting industries, including engineering firms, component manufacturers, and R&D institutions. Companies that expand into such environments can use the advanced capabilities of these related industries to support their differentiation strategies by offering superior products or processes. In contrast, when related industries are underdeveloped, companies may opt for a simpler cost leadership strategy due to limited support for advanced innovation or premium offerings.

To be successful at the business level, companies expanding internationally must consider how these factors of production; demand conditions; firm strategy, structure, and rivalry; and related and supporting industries shape the opportunities and constraints of each market. By aligning their business-level strategy with these foundational elements, companies can better position themselves to meet local market needs, capitalize on competitive advantages, and achieve sustainable success in international operations.

Porter’s Diamond Model helps explain why some nations have clusters of highly competitive industries, such as Germany’s automotive sector or Silicon Valley’s tech industry in the United States, providing insights into the strategic advantages companies may gain from operating within these clusters. These elements directly influence how companies craft and implement their strategies to achieve competitive advantage in foreign markets.

Together, these theories (among many others) offer a framework for understanding the motivations behind international business and provide a roadmap for companies seeking to expand across borders. By understanding and applying these theories, companies can make informed decisions about market selection, entry strategies, and how to compete effectively in the global landscape. Each theory offers a unique perspective that helps businesses navigate the opportunities and challenges of operating internationally, whether through focusing on efficiency, leveraging unique capabilities, learning through gradual expansion, or capitalizing on national competitive advantages.

Bibliography

Dunning, J. H. (1977). Trade, location of economic activity and the MNE: A search for an eclectic approach. The International Allocation of Economic Activity.

Fang, K., Zhou, Y., Wang, S., Ye, R., & Guo, S. (2018). Assessing national renewable energy competitiveness of the G20: A revised Porter’s diamond model. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 93, 719–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.05.011

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (2017). The internationalization process of the firm—A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. In International business (pp. 145-154). Routledge.

O’Connell, L., Clancy, P., & van Egeraat, C. (1999). Business research as an educational problem-solving heuristic—The case of Porter’s diamond. European Journal of Marketing, 33(7/8), 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569910274357

Porter, M. E. (1991). A conversation with Michael Porter: International competitive strategy from a European perspective. European Management Journal, 9(4), 355–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0263-2373(91)90096-9

Ricardo, D. (2004a). [1815] An essay on the influence of a low price of corn on the profits of stock. In Piero Sraffa (Ed.). The works and correspondence of David Ricardo: Vol. IV Pamphlets and papers 1815-1823 (pp. 1–41). Liberty Fund.

Ricardo, D. (2004b) [1817] On the principles of political economy and taxation. In Piero Sraffa (Ed.). The works and correspondence of David Ricardo: Vol. I. Liberty Fund.

van den Bosch, F. A. J., van Prooijen, A. A., & Porter, M. (1992). The competitive advantage of European nations: The impact of national culture—A missing element in Porter’s analysis?; A note on culture and competitive advantage: Response to van den Bosch and van Prooijen. European Management Journal, 10(2), 173–177.

12.6 CAGE Distance Framework

The CAGE distance framework (Ghemawat, 2001) is a tool for companies evaluating international opportunities and understanding the challenges involved in entering new global markets. Developed by Pankaj Ghemawat, it helps a company analyze the cultural, administrative, geographic, and economic distances between its home country and target foreign markets. This requires a thorough understanding of the home county as well the target countries, calling for extensive research.

These dimensions represent potential barriers to international expansion that can impact product acceptance, operational efficiency, and overall market success. By assessing these factors, companies can make informed decisions about which markets to enter, how to adapt their strategies, and what entry modes are most appropriate.

As you now know, the Porter’s Diamond Model of National Competitive Advantage focuses on the industry. The CAGE distance framework focuses on countries.

Cultural Distance

Cultural distance refers to differences in language, values, social norms, and consumer behavior between countries. Cultural differences can impact how products and services are perceived, the effectiveness of marketing messages, and the way businesses interact with customers and stakeholders. For instance, advertising campaigns that resonate in one country may not be suitable in another due to differing values and traditions. A strong understanding of cultural preferences allows companies to tailor their approaches to meet the expectations of each market, ensuring that their branding and customer interactions are culturally sensitive and effective.

Administrative Distance

Administrative distance involves differences in laws, regulations, governance, and political institutions that can create challenges for businesses entering foreign markets. This can include variations in legal systems, trade policies, tariffs, and regulatory requirements. Trade and tariff policies can both help and hinder the growth of MNCs. When there are changes in these policies, business and financial markets are disrupted. Companies may consider onshoring businesses or business operations that have been offshored. Immigration policies and enforcement can also have an influence on businesses and the economy, potentially disrupting labor markets.

Administrative differences significantly impact the ease of doing business, as firms must comply with distinct legal and bureaucratic procedures. For example, highly regulated markets may present barriers such as licensing requirements or ownership restrictions that complicate expansion plans. Companies must navigate these administrative differences effectively and adjust their strategies to comply with local laws and regulations while fostering positive relationships with local authorities.

Geographic Distance

Geographic distance considers not only the physical distance between the home country and the target market but also factors such as transportation infrastructure, time zones, and accessibility. Geographic distance can affect logistics, supply chain management, and the overall cost of moving goods and services across borders. Companies expanding into distant markets often face increased transportation costs, longer lead times, and challenges in managing the flow of goods and services. To succeed in geographically distant markets, businesses need robust supply chain strategies that can handle the complexities associated with longer shipping routes and potential logistical disruptions.

Economic Distance

Economic distance focuses on differences in income levels, consumer purchasing power, infrastructure, and overall economic development between countries. Economic distance influences how companies price their products, determine market positioning, and adapt their offerings to meet the needs of target markets. In countries with lower purchasing power, businesses may need to adjust their offerings to include more affordable options or features tailored to better match local needs. Differences in economic infrastructure, such as the availability of financial services or digital connectivity, can also impact a company’s ability to operate effectively. A deep understanding of economic distance helps companies identify which segments of the market to target and how to position their products accordingly.

You now understand how portfolio planning and the BGC matrix can be used in corporate-level strategy. MNCs use portfolio planning to make investment and divestment decisions across their portfolios of operations. For example, an MNC may decide to reinvest profits from one country into another country.

Use the CAGE distance framework analysis instrument to analyze the cultural, administrative, geographical, and economic distance between the home country and target foreign markets.

CAGE distance framework analysis instrument

Download an editable version or view this resource in Appendix 7.

The resource below provides a detailed analysis of the United States as home country and Bangladesh, Ghana, and Brazil as target foreign markets using the CAGE distance framework analysis instrument.

Download an editable version or view this resource in Appendix 7.

Application

- Use the CAGE distance analysis framework to assess two target foreign markets for potential global expansion. Use the detailed cage analysis for Bangladesh, Ghana, and Brazil as a guide. Choose two different countries to assess.

Bibliography

Carpano, C., Chrisman, J. J., & Roth, K. (1994). International strategy and environment: An assessment of the performance relationship. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(3), 639–656. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490216

Ghemawat, P. (2001). Distance still matters: The hard reality of global expansion. Harvard Business Review, 79(8), 137–147.

Miloloza, H. (2015). Differences between Croatia and EU candidate countries: The CAGE distance framework. Business Systems Research, 6(2), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1515/bsrj-2015-0011

Tokas, K., & Deb, A. K. (2020). CAGE distance framework and bilateral trade flows: Case of India. Management Research Review, 43(10), 1157–1181. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-09-2019-0386

12.7 Integration-Responsiveness Framework

Now that a firm has analyzed the opportunities and threats associated with different global markets using a tool such as the CAGE distance framework, it can use this analysis as it continues to formulate its multinational strategy. Careful consideration is necessary, as companies face diverse and conflicting environmental pressures when expanding into foreign markets.

Multinational corporations make two critical strategic decisions when formulating a multinational strategy. The first decision concerns whether the strategy is globally integrated. The second decision concerns whether the strategy is locally responsive. These two strategic decisions are captured in the integration-responsiveness framework shown in figure 12.1.

The first strategic decision addresses whether and to what degree the strategy is responsive to global integration pressures. Global integration pressures include the need to reduce costs through large-scale investments and the presence of global competitors in the firm’s target markets. Global integration pressures require firms to manage their business activities on a global basis.

The second strategic decision is whether and to what extent the strategy is responsive to local pressures. Local pressures include diverse governmental structures and differences in customer needs and preferences across countries. Local pressures compel firms to conduct their business activities on a country-by-country basis.

Combining the decisions made along these two dimensions—responsiveness to global integration pressures and responsiveness to local pressures—results in four multinational strategies: international, multidomestic, global, and transnational. An international strategy combines a low responsiveness to global integration pressures with a low responsiveness to local preferences; a multidomestic strategy combines a low responsiveness to global integration pressures with a high responsiveness to local preferences; a global strategy combines a high responsiveness to global integration pressures with a low responsiveness to local preferences; and a transnational strategy combines a high responsiveness to global integration pressures with a high responsiveness to local pressures.

International Strategy

An international strategy combines a low responsiveness to global integration pressures with a low responsiveness to local preferences. An international strategy involves expanding into foreign markets with minimal adaptation, relying on products and resources, capabilities, and core competencies developed in the home market to enter new regions with lower risk and investment. An international strategy focuses on leveraging existing resources to reach similar customer segments across borders. This approach is suited for industries where demand for local variation is low, allowing companies to maintain centralized control and achieve cost efficiencies. For example, luxury brands like Rolex use an international strategy by offering a consistent product line and brand experience worldwide, appealing to a global audience with uniform preferences. Red Bull is another brand that follows an international strategy. An Austrian brand, Red Bull is the leading energy drink, with more than $2 billion in sales every year.

Multidomestic Strategy

A multidomestic strategy combines a low responsiveness to global integration pressures with a high responsiveness to local preferences. A multidomestic strategy focuses on high local responsiveness by tailoring products, services, and business operations to meet the needs and preferences of each individual market. For example, food and beverage companies like Nestlé employ a multidomestic strategy to adapt their product offerings to local preferences, such as varying flavors and formulations based on regional tastes. Companies that adopt a multidomestic strategy treat each country as a unique market, often allowing local subsidiaries a great deal of autonomy to make decisions that align with the specific consumer expectations of that country. This strategy is particularly suitable for industries where local tastes, cultural preferences, and regulations vary significantly from one market to another. A multidomestic approach allows companies to better serve local customers by adapting their offerings; however, it may lead to higher costs due to the lack of standardized processes and economies of scale. A multidomestic strategy enables companies to closely align with local preferences, though it typically results in higher operational costs due to extensive customization.

Global Strategy

A global strategy combines a high responsiveness to global integration pressures with a low responsiveness to local preferences. A global strategy emphasizes high efficiency and the standardization of products and services across all markets. Companies employing this strategy produce and market their offerings in a highly uniform manner, seeking economies of scale and the benefits of a consistent brand image across all countries. By centralizing key functions like research and development, marketing, and production, companies can achieve cost advantages through efficiency and large-scale operations. A global strategy works best for industries where consumer needs and preferences are relatively homogeneous across different countries and where there is a significant cost advantage to producing standardized products. A global strategy achieves cost efficiencies through standardization but may overlook local consumer nuances. For example, technology companies like Apple use a global strategy by offering the same core products worldwide with little variation, ensuring consistency in quality and design while benefiting from the cost efficiencies of mass production.

Transnational Strategy

A transnational strategy combines a high responsiveness to global integration pressures with a high responsiveness to local pressures. A transnational strategy focuses on achieving both high local responsiveness and high global integration, representing a balance between the multidomestic and global strategies. Unlike purely multidomestic strategies that prioritize local adaptation or purely global strategies that emphasize standardization, the transnational strategy seeks to combine the best of both. Companies using this approach aim to standardize core operations, such as production, supply chain management, and R&D, to achieve cost efficiencies, while also allowing significant flexibility to adapt products, services, and marketing to local market needs. This dual focus requires careful coordination across diverse locations, enabling the company to respond to specific cultural and consumer preferences without sacrificing operational efficiencies. Although complex to implement, the transnational strategy can offer a competitive advantage by leveraging economies of scale alongside tailored market engagement, as exemplified by Unilever, which standardizes production but customizes product offerings and branding to suit regional tastes. Unfortunately for some, this approach requires a complex organizational structure and substantial coordination to effectively manage both global and local demands, making it challenging to implement successfully. For example, McDonald’s has thirty-six thousand locations in more than one hundred different countries, with menu items and prices that change based on the local market.

Each of these multinational strategies offers distinct advantages and challenges depending on the industry, market conditions, and overall business goals. Ultimately, the choice of multinational strategy is influenced by factors such as the degree of variation in consumer needs across markets, the intensity of competition, the nature of the industry, and the company’s resources and abilities. Successful multinational companies often align their chosen strategies with their overall competitive advantages, tailoring their approaches to achieve the best balance between global integration and local responsiveness to meet their strategic goals.

Application

- Discuss an example of a product line of a MNC that illustrates each of the four types of multinational strategy: international, multidomestic, global, and transnational. Explain in detail how each is high or low regarding global integration and local responsiveness.

Bibliography

Devinney, T. M., Midgley, D. F., & Venaik, S. (2000). The optimal performance of the global firm: Formalizing and extending the integration-responsiveness framework. Organization Science (Providence, R.I.), 11(6), 674–695. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.11.6.674.12528

Furusawa, M., & Ishida, S. (2024). Integration strategy formulation of foreign-owned R&D subsidiaries. Management Decision, 64(2). https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-08-2023-1398

Haugland, S. A. (2010). The integration-responsiveness framework and subsidiary management: A commentary. Journal of Business Research, 63(1), 94–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.03.002

Johnson, J. H. (1995). An empirical analysis of the integration-responsiveness framework: U.S. construction equipment industry firms in global competition. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(3), 621–635. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490189

Kedia, B. L., Nordtvedt, R., & Pérez, L. M. (2002). International business strategies, decision-making theories, and leadership styles: An integrated framework. Competitiveness Review, 12(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb046433

Lin, S.-L., & Hsieh, A.-T. (2010). The integration-responsiveness framework and subsidiary management: A response. Journal of Business Research, 63(8), 911–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.04.031

Morschett, D., Schramm-Klein, H., & Zentes, J. (2010). The integration/responsiveness-framework. In strategic international management (pp. 29–50). Gabler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-6331-4_3

Rao, P. (2016). Integration-responsiveness framework: Indian IT subsidiaries in Mexico. Journal of Indian Business Research, 8(4), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-10-2015-0111

Roth, K., & Morrison, A. J. (1990). An empirical analysis of the integration-responsiveness framework in global industries. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(4), 541–564. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490341

Taggart, J. H. (1997). An evaluation of the integration-responsiveness framework: MNC manufacturing subsidiaries in the UK. Management International Review, 37(4), 295–318.

Venaik, S., Midgley, D. F., & Devinney, T. M. (2004). A new perspective on the integration-responsiveness pressures confronting multinational firms. Management International Review, 44(1), 15-48.

12.8 Choice of Entry Mode

Choosing the appropriate entry mode is a crucial decision for firms expanding internationally, as it directly influences the level of control, risk, required investment, and overall potential for success. Entry modes vary in terms of risk and commitment, ranging from low-risk, low-investment options to high-risk, high-commitment strategies. Firms with limited resources or a low tolerance for risk may favor modes that require minimal capital and offer lower exposure, such as exporting, while those seeking greater control and long-term presence may opt for more committed approaches, like wholly owned subsidiaries. Common international entry modes, ordered from lowest to highest commitment, include exporting, licensing and franchising, joint ventures, strategic alliances, wholly owned subsidiaries, and foreign direct investment, each offering unique benefits and challenges depending on a firm’s strategic goals and market characteristics.

Exporting

Exporting is often the first step for many companies seeking to enter international markets. It involves producing goods domestically and shipping them to foreign markets for sale, allowing companies to expand without investing heavily in foreign facilities. Exporting offers a low-risk way to test the viability of foreign markets and allows companies to retain control over production processes. However, exporting can also lead to increased logistics costs and may expose companies to tariff and nontariff barriers in their target countries. Exporting is suitable for companies with limited international experience or for those wanting to test the waters before making more substantial investments abroad.

Licensing and Franchising

Licensing and franchising are popular entry modes for companies that want to leverage the capabilities of local partners without establishing a direct physical presence. Licensing involves granting a foreign entity the rights to use the company’s intellectual property, such as technology, patents, or trademarks, in exchange for a fee or royalty. This entry mode allows companies to expand with minimal investment and risk, as the licensee bears the cost of setting up operations in the target market. Similarly, franchising allows companies to license their business models, brands, and operational systems to foreign franchisees, who manage and operate the business locally. Franchising is commonly used by service-oriented firms, particularly in the hospitality and food service industries, such as McDonald’s and Marriott. While licensing and franchising help companies grow quickly, they often involve a loss of control over the quality of products and services, which can affect brand consistency across different markets.

Joint Venture

A joint venture is an entry mode where a company partners with a local firm to establish a new entity in the foreign market. This approach provides both parties with shared ownership, combining the local knowledge and market access of the domestic partner with the foreign firm’s expertise and technology. Joint ventures are particularly advantageous in countries with regulatory requirements that mandate local ownership or where navigating cultural and political environments is challenging for foreign firms. A notable advantage of joint ventures is the ability to reduce risk by sharing costs and to benefit from the established relationships of the local partner. However, managing joint ventures can be challenging due to potential conflicts of interest, differences in strategic objectives, and challenges in decision-making.

Strategic Alliances

Strategic alliances represent another entry mode that involves partnering with a foreign firm without forming a separate legal entity. Strategic alliances are often less formal than joint ventures and can include collaborations on specific projects, co-marketing agreements, or joint product development. These alliances allow companies to gain quick access to new markets, share expertise, and distribute costs and risks. For instance, tech companies often form alliances to collaborate on R&D initiatives, allowing both parties to benefit from shared technological advancements. However, strategic alliances may suffer from a lack of clearly defined control, and the success of the partnership often depends on the mutual trust and commitment of both parties.

Wholly Owned Subsidiaries

Wholly owned subsidiaries involve full ownership and control of foreign operations and can be established through either greenfield investments or acquisitions. In a greenfield investment, a company builds its operations from scratch in the foreign market, allowing for complete customization and control of the new facility. Alternatively, a firm may acquire an existing local company to gain immediate market access, existing customers, and operational capabilities. Wholly owned subsidiaries provide the highest level of control over international operations, allowing companies to fully integrate their culture, processes, and standards across borders. However, they are also the most resource-intensive and carry significant risk due to the large capital investment required. This entry mode is suitable for firms that prioritize control over their foreign operations and are willing to invest heavily in expanding their international footprints.

Foreign Direct Investment

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is a critical aspect of multinational business strategy, involving the establishment of significant ownership in foreign markets. FDI allows companies to maintain a high level of control over their operations abroad, facilitating deeper market integration and the ability to adapt business strategies to local environments effectively. Unlike other entry modes, such as exporting or licensing, FDI requires a substantial commitment of resources and carries higher risks, including exposure to political, economic, and operational uncertainties. The benefits of FDI include greater access to local knowledge, increased control over production and distribution, and the potential for long-term growth in key international markets. FDI is an essential consideration for companies seeking to establish a robust presence in foreign territories and to leverage local advantages while building a sustainable competitive position.

Application

- Think of the companies you have studied in your business education. Feel free to conduct research if you need to.

- Discuss one example of a company that has used each of the entry modes to multinational business: exporting, licensing and franchising, joint venture, strategic alliance, wholly owned subsidiaries, foreign direct investment.

Bibliography

Ekeledo, I., & Sivakumar, K. (2004). International market entry mode strategies of manufacturing firms and service firms: A resource-based perspective. International Marketing Review, 21(1), 68–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330410522943

Liu, H. (2018). Foreign direct investment and strategic alliances in Europe (1st ed.). Routledge.

Schellenberg, M., Harker, M. J., & Jafari, A. (2018). International market entry mode—A systematic literature review. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 26(7), 601–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2017.1339114

Stoian, M., Rialp, J., & Dimitratos, P. (2017). SME networks and international performance: Unveiling the significance of foreign market entry mode. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(1), 128–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12241

Surdu, I., Mellahi, K., & Glaister, K. (2018). Emerging market multinationals’ international equity-based entry mode strategies: Review of theoretical foundations and future directions. International Marketing Review, 35(2), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-10-2015-0228

12.9 Analyze Multinational Strategy

When you conduct a case analysis, you analyze a firm’s multinational strategy. This is step six in the case analysis process.

6. As appropriate to the case, analyze strategies: Corporate-level, business-level, innovation, sustainability and ethics, technology, and multinational strategies.

- Use strategic management analytical frameworks to analyze, interpret, and evaluate strategies.

- Ensure line of sight and congruence within analysis of each strategy.

12.10 Why Multinational Strategy Is Important to Business Graduates

For business graduates starting as business support unit managers in support business units in large multinational companies (such as marketing managers), multinational strategy has a direct influence on the implementation of functional-level strategy. How the company will decide to what degree the company is responsive to global integration pressures and whether and to what extent the firm is responsive to local pressures has a direct impact on business support unit managers. Whether a company formulates an international, multidomestic, global, or transnational strategy, business executives and divisional or strategic business unit managers in large multinational businesses need data and data analysis the business support unit managers have direct access to.

Business graduates that enter either internal or external consulting roles require a high level of competence with multinational strategy to communicate with business executives in multinational firms how their consulting projects fit into the overall multinational strategy of the firm. When business graduates that serve as either internal or external consultants to companies that are currently not engaging in international business, competency with multinational strategy is important so they can work with company executives that may be consider taking their firms global. Many large consulting firms are multinational. For business graduates who are or will become entrepreneurs, fluency with multinational strategy is essential to establishing and growing a successful firm if the goal is international expansion.

12.11 Conclusion

Expanding into international markets is a complex but rewarding endeavor that requires careful consideration of strategic motivations, market conditions, and the potential barriers that could impact success. By employing a comprehensive approach that includes evaluating motivations for expansion and by selecting the most appropriate entry modes, companies can maximize their chances of thriving globally. Theories such as the OLI paradigm and frameworks like the CAGE distance framework and the integration responsiveness framework provide valuable insights to help firms assess which strategies and markets are best aligned with their objectives. Ultimately, successful international expansion requires balancing the need for local responsiveness with the pursuit of global efficiencies, navigating risks effectively, and making informed choices about where and how to enter new markets.

Use these questions to test your knowledge of the chapter:

- Describe multinational strategy and its relationship to business-level strategy. Do all firms formulate and implement multinational strategy?

- Discuss the history of global commerce.

- Discuss the motivations and risks associated with multinational strategy.

- Discuss the key elements of eight theories of multinational business. Which ones appeal to you the most and why? How can these theories inform multinational strategy?

- Discuss the CAGE distance framework and its four dimensions. Give examples of each dimension. How is the CAGE distance framework used in formulating multinational strategy?

- Discuss the integration-responsiveness framework. Explain the two critical strategic decisions that strategic leaders and managers make when formulating a multinational strategy and how these relates to four multinational strategies.

- There are multiple entry modes when considering global expansion. Discuss each of these, and give examples.

- Describe how competence with multinational strategy is relevant and important to you.

Now you are competent with multinational strategy. Your hard work has paid off! Only one more chapter to go!

Figure Descriptions

Figure 12.1: First quadrant of an X-Y axis with four purple boxes. The x-axis represents responsiveness to local pressures and the y-axis represents responsiveness to global integration pressures. Both axes range from low to high. Low responsiveness to local pressures and low responsiveness to global integration pressures is labeled international. High responsiveness to local pressures and high responsiveness to global integration pressures is labeled transnational. High responsiveness to local pressures and low responsiveness to global integration pressures is labeled multidomestic. Low responsiveness to local pressures and high responsiveness to global integration pressures is labeled global.

Figure References

Figure 12.1: Integration-responsiveness framework. Kindred Grey. 2025. CC BY.

Figure 12.2: Red Bull. Cefalophore. 2024. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:8.4_floz_can_of_Red_Bull_Energy_Drink.jpg

A multinational corporation is a firm that has operations in more than one country.

Multinational strategies are strategies that are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level that address different ways to position the company in multinational markets. These include international, multidomestic, global, and transnational strategies.

Opportunity cost refers to the loss of potential gain from alternative options that were not pursued.

For example: Idle cash balances represent an opportunity cost in terms of lost interest.

A multidomestic strategy combines a low responsiveness to global integration pressures with a high responsiveness to local preferences. Multidomestic strategy involves adaptation of products, services, and operations to align closely with the unique demands of each local market, prioritizing responsiveness over global standardization.

A global strategy combines a high responsiveness to global integration pressures with a low responsiveness to local preferences. Global strategy occurs when a company standardizes its products, services, and operations across all international markets to achieve efficiency and consistency.

Transnational strategy is a strategy involving the balance of global efficiency with local responsiveness by standardizing core elements while adapting others to meet the unique needs of individual markets.

Exporting occurs when a company produces goods and sells them in foreign markets.

Licensing is an entry mode in which a company allows a foreign company to purchase the rights to produce, sell, or use its products in exchange for royalties or a fee.

Franchising is an entry mode in which a company (the franchisor) grants a foreign partner (the franchisee) the right to use its proprietary business assets (e.g., products, brand, knowledge) in exchange for fees and ongoing royalties.

A joint venture is established when two parent companies establish a new shared entity, a child company.

A strategic alliance is a mutually beneficial contractual relationships between two independent organizations.

A wholly owned subsidiary is a company whose common stock is 100% owned by another company. In the context of multinational corporations, wholly owned subsidiaries involve full ownership and control of foreign operations. They can be established through either greenfield investments or acquisitions.

When a company builds its operations from scratch in the foreign market, allowing for complete customization and control of the new facility.

FDI refers to a company investing in a business in another country.