10. Formulate Sustainability and Ethics Strategy

After engaging with this chapter, you will understand and be able to apply the following concepts:

- Sustainability and ethics strategy

- Disruptive megatrends and how they impact business strategy

- The drivers of climate change as the defining megatrend and approaches to fight the climate crisis

- The concept of sustainability and the stakeholder-driven business case for companies to implement business sustainability strategies

- The pros and cons of companies embracing a social responsibility beyond the profit motive

- The triple bottom line approach.

- The concept and content of corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategy

- Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) strategies as the latest and most relevant concept of sustainability

- The elements of a robust ethics strategy

- Contemporary issues of corporate ethics that are shaping the business strategy agenda

- Why sustainability and ethics strategy is important to business graduates

When you finish Chapter 10, you will be equipped to analyze sustainability and ethics strategy.

10.1 Introduction

This chapter covers sustainability and ethics strategy. This entails you learning about megatrends, including climate change, that drive sustainability and ethics strategy. Then you learn about sustainability strategy in more detail, including its history and evolution. You learn about the continuing impact of the triple bottom line approach. The chapter covers two crucial sustainability strategies: corporate social responsibility (CSR) and today’s most current framing of sustainability strategy, the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) approach. Next you learn about ethics strategy and contemporary questions of corporate ethics. Then you learn how to analyze sustainability and ethics strategy. Finally, the chapter concludes with a discussion of why sustainability and ethics strategy is important to business graduates.

10.2 Sustainability and Ethics Strategy

Like all strategy formulation, formulating sustainability and ethics strategy answers the question “Where are we going?” This form of strategy addresses how a firm can use sustainability and business ethics to establish a competitive advantage over its competitors by better meeting evolving customer demands and the expectations of important business stakeholders. All firms need to address sustainability and ethics.

Like innovation, sustainability and ethics is another strategy focus that is formulated at the strategic business unit level of a company and embedded in business level-strategy, answering the strategic question of how specifically a firm is going to win or compete in its chosen markets and market segments.

Like all strategy, sustainability and ethics strategy focuses on an outside-in perspective. Companies need to carefully monitor their external environments. They need to analyze trends and formulate strategies that are forward-looking. Robust sustainability and ethics strategy takes into account the volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous nature of the firm’s external environment, where change and disruption have become the new normal.

This chapter analyzes how changes in the external environment of the firm drive strategic responses with companies embracing their corporate social responsibility, developing environmental, social, and governance strategies and treating corporate business ethics as a possible source of winning in the market versus just a legalistic approach to stay compliant.

Like all strategy formulation, formulating sustainability and ethics strategy answers the question “Where are we going?” and addresses how a firm can use sustainability and business ethics to establish a competitive advantage. All firms need to address sustainability and ethics strategy. Like innovation, sustainability and ethics is another strategy focus that is formulated at the strategic business unit level of a company and embedded in business-level strategy, answering the strategic question “Right to win?”

Bibliography

Senge, P. M., Smith, B., Kruschwitz, N., Laur, J., & Schley, S. (2010). The necessary revolution: How individuals and organizations are working together to create a sustainable world. Crown.

10.3 Megatrends and Climate Change

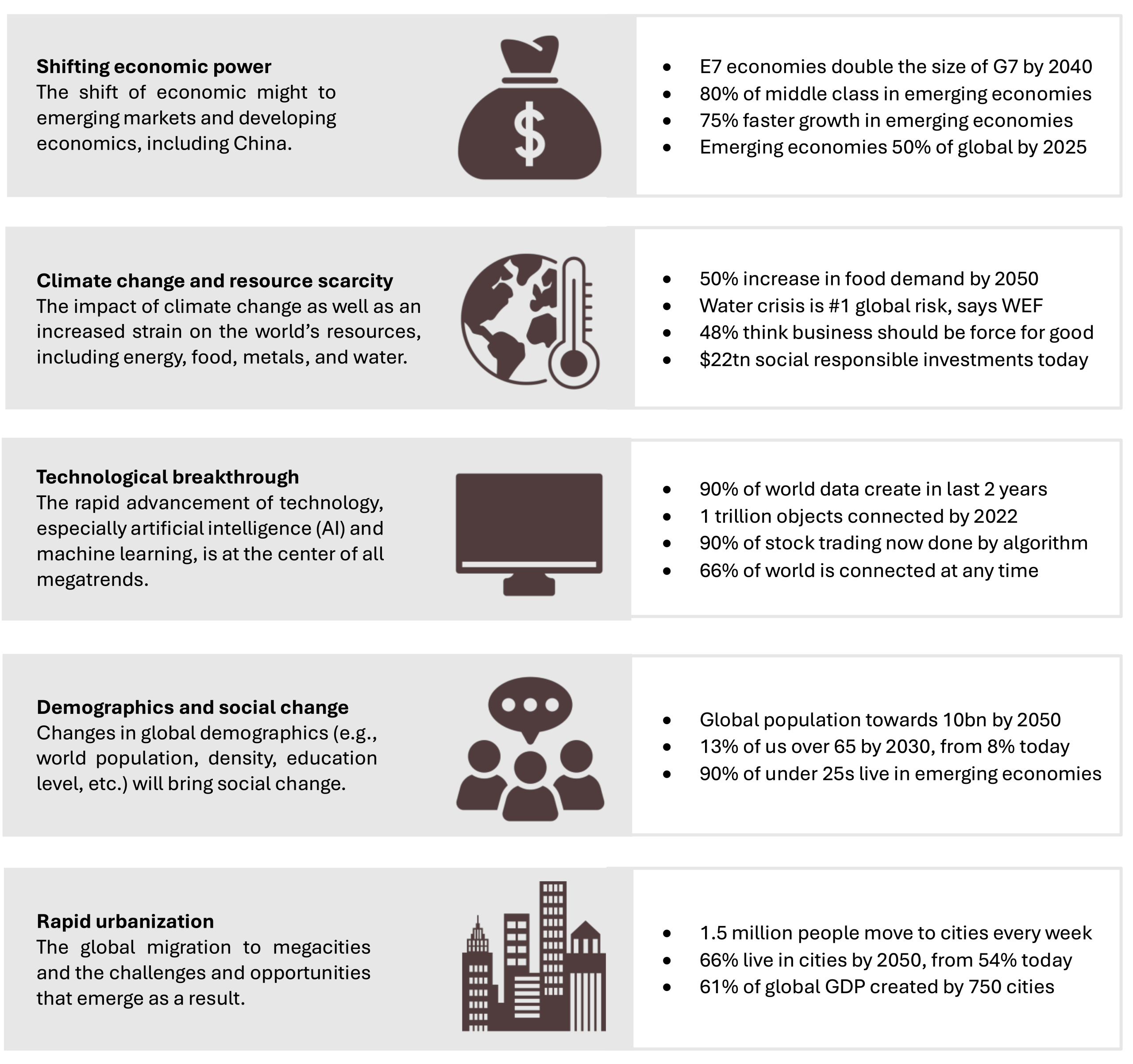

Positioning a business strategically for success requires a thorough analysis of disruptive megatrends, which are deep and profound trends that are global in scope and long term in effect. These must be considered for strategy formulation. Important disruptive megatrends relevant for business rest in technological transformation (for example, AI, cloud and quantum computing, big data, and automation) as well as shifts in economic power to emerging countries, rapid urbanization, global population growth, supply chain disruptions in an increasingly globalized business environment, aging Western populations, young populations in emerging countries, geopolitical tensions, social change, climate change, and resource scarcity.

Figure 10.1 provides an overview of disruptive megatrends that companies need to consider in their strategy development and implementation.

Climate Change

Addressing climate change is the defining challenge of our time and is one megatrend that threatens to disrupt modern society. Climate change is a significant variation of average weather conditions (warmer, wetter, or drier) over several decades. When the earth absorbs the sun’s energy, or when atmospheric gases prevent heat released by the earth from radiating into space (the greenhouse effect), the planet warms. Global warming refers to the increase in the planet’s overall average temperature in recent decades. Global warming is part of climate change and is driven by greenhouse gases (GHGs), with carbon dioxide (CO2) being the main driver of global warming. The burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas for electricity, heat, and transportation is the main root cause of the huge increase of CO2 emissions. CO2 concentration is now at its highest level in 800,000 years, leading to a rapidly increasing global temperature which is causing draughts, rising sea levels, extreme weather events, food shortages, the reduction of biodiversity, lack of fresh water and climate refugees, among other issues. In his opening remarks to COP27 on November 7, 2022, United Nations (UN) Secretary Antonio Guterres had some very clear, powerful, and concerning messages to the world regarding climate change:

“We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator.”

“We are in the fight of our lives, and we are losing.”

“Greenhouse gas emissions keep growing, global temperatures keep rising, and our planet is fast approaching tipping points that will make climate chaos irreversible.”

To limit the negative effects of climate change, almost all countries in the world committed to a reduction of CO2 emissions in the Paris Agreement in 2015. The target of the Paris Agreement is limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial level. To achieve this, countries committed to a net-zero CO2 target by 2050.

These commitments have implications for all businesses around the world, leading to strategic questions like:

- What does my industry and market look like in a net-zero world?

- How do I transform and decarbonize my business model?

- How do I identify, mitigate, and address climate risk in my operations?

- How do I climate-proof my operations?

- How do I manage my global supply chain, and how do I cooperate with suppliers around the world who contribute to my firm’s greenhouse gas footprint?

- How do I stay legally compliant with current and emerging climate regulations and laws?

- How do I report on the environmental (and social) performance of my firm?

Application

- Refer to figure 10.1. Choose one of the disruptive megatrends that interests you the most.

- Explain how the disruptive megatrend impacts strategy formulation and implementation.

Megatrends are deep and profound trends that are global in scope and long term in effect. Important disruptive megatrends relevant for business involve technological transformation, shifting economic power to emerging countries, rapid urbanization, global population growth, supply chain disruptions, aging Western populations, young populations in emerging countries, geopolitical tensions, social change, climate change, and resource scarcity. Positioning a business strategically for success requires a thorough analysis and integration of disruptive megatrends.

Addressing climate change is the defining challenge of our time and is one megatrend that threatens to disrupt modern society. Climate change is a significant variation of average weather conditions over several decades. When the earth absorbs the sun’s energy, or when atmospheric gases prevent heat released by the earth from radiating into space (the greenhouse effect), the planet warms. Global warming refers to the increase in the planet’s overall average temperature in recent decades.

Bibliography

Agrawal, R. (Ed.). (2023). Industry 4.0 and climate change. CRC Press.

Bash, C., Faraboschi, P., Frachtenberg, E., Laplante, P., Saracco, R., & Milojicic, D. (2023). Megatrends. Computer (Long Beach, Calif.), 56(7), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2023.3271428

D’Cruz, P., Du, S., Noronha, E., Parboteeah, K. P., Trittin-Ulbrich, H., & Whelan, G. (2022). Technology, megatrends and work: Thoughts on the future of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 180(3), 879–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05240-9

Hauge, J. (2023). The future of the factory: How megatrends are changing industrialization (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198861584.001.0001

Lebedeva, M. M., & Kuznetsov, D. A. (Eds.). (2023). Megatrends of world politics: Globalization, integration and democratization. Routledge.

United Nations. (2022). Secretary-General’s remarks to high-level opening of COP27. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2022-11-07/secretary-generals-remarks-high-level-opening-of-cop27

United Nations. (2015). The Paris Agreement. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement

10.4 Sustainability Strategy

Addressing the issues of climate change, resource scarcity, biodiversity, human rights, social issues, and social justice are covered by the term sustainability. Sustainability is defined by the UN Commission for Sustainable Development (Brundtland Commission) as meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Sustainability strategy is a company’s strategy to reduce adverse environmental and social impacts resulting from business operations while still pursuing profitable growth. Strategies that fall under this umbrella include corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) strategies. Sustainability is a business imperative and should be at the core of every business’s strategy and operations.

Figure 10.2 shows a few examples of firms’ sustainability statements.

| Company | Sustainability statement |

|---|---|

| Ford | Vision For The Future: We aim to reach carbon neutrality no later than 2050. This encompasses our entire impact on the planet – from the emissions from our vehicles to the power in our factories, to our suppliers. |

| McDonald’s | Our Planet: We’re helping to drive climate action, protecting natural resources, reducing waste, and transitioning to more sustainable packaging and toys. |

| Oatly | So, you may be wondering why a company needs a to-do list or how long a company’s to-do list might be. Hopefully, this explains it or leaves you with your own questions. Anyway, it’s our to-do list to take important steps toward our vision for a food system that is better for people and the planet. But it’s not just a to-do list! It’s our sustainability plan outlining the actions we will take to meet our sustainability ambitions. |

| Tesla | Tesla’s mission is to accelerate the world's transition to sustainable energy. Sustainability is integral to Tesla, and it is central to its mission. |

| Avon | We’re open to all. Every member of our team has the right to personal self-expression such as dress, hair, or other forms of body adornment. We believe in inclusive beauty and support self-expression by challenging stereotypes, supporting freedom of expression, and representing a wide range of people. |

Figure 10.2: Sustainability statements from companies

Do Companies Have a Social Responsibility beyond Profit?

There is a decades-long controversy over whether business should (or even must) support environmental and social issues or whether they should just focus on generating profits. The strongest supporter of the profit focus is American economist and Nobel Prize Winner in Economic Sciences, Milton Friedman. He stated that “the business of business is doing business.” He believed that there is one and only one social responsibility of business: “To use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud” (Forder, 2019).

On the other hand, Theodore Levitt, American economist and professor at the Harvard Business School stated, “Although profits are required for business just like eating is required for living, profit is not the purpose of business any more than eating is the purpose of life” (Levitt, 1983).

There is a strong argument to be made that companies do have an ethical and moral obligation to give back to society and support environmental and social issues. With great power, there comes great responsibility. Companies have the resources available to make a positive difference, and it seems to be the right and ethical thing to do.

Business Case for Sustainability Strategy

As you have just seen, there are different perspectives on whether the purpose of business includes a social responsibility beyond just making profits. We now want to go beyond an ethical assessment toward a clear financial business case in favor of sustainable business management. This business case is driven by the expectations of business’ main stakeholders: customers, employees, investors, and regulators.

Customers

- Eighty percent of consumers are more likely to buy from a company that stands up for environmental issues (PWC, 2023).

- Ninety percent of Gen-Zs believe companies should act on social issues, and 90 percent of millennials in the U.S. would switch brands to those championing a cause (BCG, 2021).

- Eighty-seven percent of Americans will purchase a product because a company advocated for an issue they care about, whereas 76 percent will refuse to purchase a company’s product from a company supporting issues contrary to their beliefs (Cone Communications CSR Study, 2017).

While customers have always supported sustainability to a high degree, the current game changer is the customers’ willingness to pay more for sustainable products and solutions, basically voting with their wallets in support of sustainability. Offering sustainable solutions helps companies to win with their customers and in their chosen markets and market segments.

Employees

- Forty percent of millennials state that sustainability was a consideration in their job choice (BCG).

- Over 40 percent of Gen-Zs and millennials would switch jobs over climate concerns (Segal, 2024).

- Eighty-three percent of employees are more likely to work for a company that addresses environmental and social issues in their business (PWC, 2021).

- Eighty-six percent of employees prefer to support or work for companies that care about the same issues they do (PWC, 2021).

Talent attraction, talent retention, and managing an engaged and committed workforce depends on the strength of companies’ sustainability strategies.

Investors

- Eighty-eight percent of investors believe companies that prioritize sustainability initiatives represent better opportunities for long-term returns than companies that do not (PWC, 2022).

- Beyond strong financial performance, institutional investors demand a strong environmental and social performance from the companies in which they invest. They see a lack of social commitment and a business model that doesn’t transform the company’s business toward sustainability as signs of a financial investment risk.

- In the words of Larry Fink, Chairman and CEO of the world’s largest asset management firm, BlackRock: “To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society. Companies must benefit all of their stakeholders.”

Access to capital and capital costs depends on a robust sustainability strategy that convinces private and institutional investors that the company is well positioned with a clear purpose and a meaningful management of climate risk in their business model.

Government and Regulators

- Governments and regulators have set the bold ambition for countries to become carbon-neutral by 2050. This is the direct consequence of countries committing to the Paris Agreement. Regulatory approaches to achieve this include regulation on the industry sector level designed to limit and continuously reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the implementation of a carbon tax to make the use of fossil energy more expensive, and tax breaks and financial subsidiaries in support of a business transformation toward a low-carbon business model.

- Regulators introduce carbon pricing and regulations on a sector level to reduce CO2 emissions. For example, California outlawed the sale of new fossil fuel cars as of 2035.

- There is significant pressure on businesses to comply with quickly evolving new environmental regulation and laws and a clear mandate to decarbonize companies’ business models.

A proactive approach to sustainability helps companies to stay compliant and ahead of the curve in terms of legislation and regulation. Instead of just passively reacting to new legislation and regulation, companies can proactively factor new laws and regulations into their business models, excel in reporting and disclosure, and transform their business models ahead of the competition.

Sustainability strategies drive positive performance by saving on costs through lower energy and water consumption, waste reduction, pollution control, improved employee recruitment, retention, and work productivity, improved corporate reputation and brand recognition, and the creation of new revenue-generating opportunities through innovation, new products, and new markets. Sustainability also supports cost savings through risk management in global supply chains, tax credits and subsidies, legal and regulatory compliance, positive community relations, and better access to capital.

Figure 10.5 summarizes the business case for sustainability strategies.

This positive financial business case of sustainable business models has also been supported by a large-scale meta-study of the New York University Center for Sustainable Business. The Center examined the relationship between ESG and financial performance in 245 research studies between 2015 and 2020. The results of this study showed that a majority of studies (58 percent) indicated a positive impact of ESG and business sustainability on financial performance, whereas only 8 percent show a negative impact (Whelan, Atz, Van Holt, & Clark, 2021).

Application

- Research the sustainability statements for three companies you admire. Discuss whether each company is following its sustainability commitments and how this impacts profits.

Sustainability is defined by the UN Commission for Sustainable Development (Brundtland Commission) as meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Sustainability strategy is a company’s strategy to reduce adverse environmental and social impacts resulting from business operations while still pursuing profitable growth. Strategies that fall under the umbrella of sustainable strategies include corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) strategies. Businesses need to balance economic, social, environmental, and legal and regulatory obligations in order to satisfy stakeholder desires and therefore must assume broad responsibilities that include complying with social norms and expectations. There is a clear financial business case in support of sustainability strategy driven by customers, employees, investors, and regulatory agencies.

Bibliography

Bell, M. J. (2021, March 9). Why ESG performance is growing in importance for investors. EY. https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/assurance/why-esg-performance-is-growing-in-importance-for-investors

Biela-Weyenberg, A. (2023, August 15). Improve supply chain sustainability. Oracle. https://www.oracle.com/scm/sustainability/improve-supply-chain-sustainability

Boston Consulting Group. (2021, April). Executive perspectives: Time for climate action. BCG. https://media-publications.bcg.com/BCG-Executive-Perspectives-Time-for-Climate-Action.pdf

Carroll, A. B., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2012). Business and society: Ethics, sustainability, and shareholder management. South-Western Cengage.

Carroll, A. B. (1991, July–August). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48.

Cone Communications. (2017). 2017 Cone Communications CSR study. Engage for Good. https://engageforgood.com/2017-cone-communications-csr-study

IBM. (n.d.). Business sustainability. https://www.ibm.com/topics/business-sustainability

Forder, J. (2019). Milton Friedman (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-38784-4

Fink, L. (2018). 2018 letter to CEOs. BlackRock. https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/2018-larry-fink-ceo-letter

Gelfand, A. (2024, May 2). Big investors say they use ESG to reduce risk, but mostly focus on the ‘E’. Stanford Graduate School of Business. https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/big-investors-say-they-use-esg-reduce-risk-mostly-focus-e-g

Lawrence, A. T., & Weber, J. (2011). Business and society: Stakeholders, ethics, public policy (13th ed.). McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Levitt, T. (1983). The marketing imagination. Free Press.

Office of Governor Gavin Newsom. (2020, September 23). Governor Newsom announces California will phase out gasoline-powered cars & drastically reduce demand for fossil fuel in California’s fight against climate change. CA.gov. https://www.gov.ca.gov/2020/09/23/governor-newsom-announces-california-will-phase-out-gasoline-powered-cars-drastically-reduce-demand-for-fossil-fuel-in-californias-fight-against-climate-change

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2023). On sustainability, consumers have made up their mind. PwC. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/c-suite-insights/the-leadership-agenda/on-sustainability-consumers-have-made-up-their-mind.html

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2022). Global investor survey 2022. PwC. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/esg/global-investor-survey-2022.html

Senge, P. M., Smith, B. Bryan, Kruschwitz, N., Laur, J., & Schley, S. (2010). The necessary revolution: How individuals and organizations are working together to create a sustainable world. Crown.

Segal, M. (2024, May 16). More than 40% of Gen Z, millennials would change jobs over climate concerns, Deloitte survey finds. ESG Today. https://www.esgtoday.com/more-than-40-of-gen-z-millennials-would-change-jobs-over-climate-concerns-deloitte-survey-finds

Stobierski, T. (2021, June 15). 16 important statistics about corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business School Online. https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/corporate-social-responsibility-statistics

United Nations. (2020). The sustainable development goals report 2020. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2020.pdf

U.S. Department of Energy. (n.d.). Decarbonizing the U.S. economy by 2050: National blueprint for the buildings sector. https://www.energy.gov/eere/decarbonizing-us-economy-2050-national-blueprint-buildings-sector

United Nations. (2015). The Paris Agreement. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement

10.5 Triple Bottom Line

Closely related to the positive financial business case of sustainable business is the triple bottom line concept. Business leader Sir Richard Branson once said, “Doing good is good for business.” This reflects a growing mindset in modern companies where social and environmental responsibility go hand in hand with profitability. This is often reflected in a firm’s purpose and values. It is also a focus of corporate social responsibility and environmental, social, and governance strategy.

Instead of asserting that doing positive things for the environment and society comes at the expense of profit, the triple bottom line states that a good environmental and social performance will support the financial performance of companies. There is no tradeoff between profit and people and the environment; in fact, there is a positive correlation. Companies use sustainability strategies to enhance financial performance, and sustainability becomes a driver of competitive differentiation.

The triple bottom line framework emphasizes a broader view that focuses on the three Ps: people, planet, and profits. These may also be referred to as social/societal, environmental, economic/financial. The triple bottom line ensures that organizations consider not only financial success but also their impact on society (people) and the environment (planet). Although the concept originated in the 1980s, it gained significant traction in the late 1990s as businesses began recognizing that sustainable and ethical practices lead to long-term success. Almost all companies have embraced this approach, prioritizing environmental sustainability and social responsibility alongside their financial goals.

The logic in support of the business case for sustainable business management and the triple bottom line approach can be summarized by the following statements:

- Doing well by doing good

- Making “doing the right thing” profitable

- Creating a better world through better business

Deloitte demonstrates its commitment to the planet and people through an integrated approach to sustainability and social impact. The company’s environmental pledge, embedded in its strategy, includes ambitious goals to achieve net-zero emissions by 2030 and drive climate-positive initiatives across industries. Deloitte doesn’t stop at environmental leadership; it also prioritizes the people aspect of the triple bottom line by focusing on creating equitable opportunities within the communities it serves. Through programs like its WorldClass initiative, Deloitte aims to empower 100 million individuals worldwide by 2030 through education and skills development, especially in underserved populations. Balancing these commitments with strong financial performance, Deloitte demonstrates how large organizations can be profitable while remaining socially responsible and environmentally conscious. Deloitte encourages its employees to learn skills that benefit both the firm and individuals through its Graduate School Assistance Program. The program helps to send high-performing consultants to top graduate schools. In doing so, Deloitte hopes to encourage top talent to choose employment with the firm. The program provides a reward for the high-achieving employees who it wishes to retain. This is evidence of Deloitte’s commitment to the people pillar of the triple bottom line.

The triple bottom line framework emphasizes a broader view that focuses on the three P’s: people, planet, and profits. There is no tradeoff between profit and people and the environment; instead there is a positive correlation. Companies use sustainability strategy to enhance financial performance, and sustainability becomes a driver of competitive differentiation.

Bibliography

Anderson, R. C. (2009). Confessions of a radical industrialist: Profits, people, purpose—Doing business by respecting the earth. St. Martin’s Press.

Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11), 1304–1320.

Bals, L., & Tate, W. (2017). Implementing triple bottom line sustainability into global supply chains (1st ed.). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351285124

Bowden, A. R., Lane, M. R., & Martin, J. H. (2001). Triple bottom line risk management: Enhancing profit, environmental performance, and community benefits. J. Wiley.

Henriques, A., & Richardson, J. (2004). The triple bottom line, does it all add up?: Assessing the sustainability of business and CSR. Earthscan Publications.

Jayachandran, S., Kalaignanam, K., & Eilert, M. (2103). Product and environmental social performance: Varying effects on firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 34(10), 1255–1264.

Norman, W., & MacDonald, C. (2004). Getting to the bottom of “triple bottom line.” Business Ethics Quarterly, 14(2), 243–262.

Willard, B. (2012). The new sustainability advantage: Seven business case benefits of a triple bottom line (10th anniversary ed.). New Society Publishers.

Senge, P. M., Smith, B. Bryan, Kruschwitz, N., Laur, J., & Schley, S. (2010). The necessary revolution: How individuals and organizations are working together to create a sustainable world. Crown.

Wang, T., & Bansal, P. (2012). Social responsibility in new ventures: Profiting from a long-term orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 33, 1135–1153.

10.6 Corporate Social Responsibility: A Sustainability Strategy

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is the idea that a business has a responsibility to the society in which it operates. CSR is an approach where a company operates in ways that enhance society and the environment while pursuing its profit goal. CSR can promote a positive reputation with stakeholders and a positive brand image for the company. With the parallel pursuit of environmental, social, and economic objectives, CSR shows many parallels with the triple bottom line approach (profit, people, planet). One of the main drivers and advantages of CSR is that it acknowledges and embraces the fact that business operates in a multi-stakeholder context.

Corporate social responsibility strategy is a sustainability strategy that focuses on the tenants of the CSR approach. Assuming corporate responsibility not only for a company’s financial results but also considering various stakeholders and their environmental and social interests strengthens a business’s social license to operate. It enhances relationships and drives support of various primary and secondary stakeholders whose support a company needs to stay successful in the long term.

Beyond allowing a company to thrive in a multi-stakeholder society, CSR encourages long-term thinking, drives innovation and cost savings, enhances brand differentiation, and furthers customer and employee engagement. Beyond customers and employees, investors and governmental regulators are additional important stakeholders. CSR improves business reputation and standing, provides access to investment and funding opportunities, and generates positive publicity and support by the general public and media, also known as the “court of public opinion.”

Let’s take Levi Strauss & Co. as an example of what companies do in support of their CSR strategies. Levi’s explains how it supports society and the environment through these specific activities:

- We had the courage to reject racial segregation: Our first desegregated sewing factory opened in Blackstone, Virginia in 1960.

- We championed corporate integrity through transparency: Our Terms of Engagement were instituted worldwide in 1991, ensuring worker protection at every point of the supply chain.

- We encouraged empathy in the face of fear: Our leaders and employees came together in 1982 to educate the public on issues facing the LGBTQ+ community.

- We’re making things better & thinking sustainability first.

- We’re collaborating with suppliers on programs that improve the lives of apparel workers.

- We’re committed to saving arts education (Levi’s, n.d.).

You can easily see how Levi’s targets various stakeholders, how it wants to improve social matters (improving the lives of apparel workers) and environmental matters (prioritizing sustainability). You can also easily see how consumers may identify with these activities and reward Levi’s with their business, which would then drive Levi’s financial performance as a result of brand loyalty and higher willingness to pay by consumers.

Other typical activities of a socially responsible company include making products that are safe, obeying laws and regulations in all aspects of business, promoting honest and ethical employee behavior, committing to a safe workplace for all employees, avoiding misleading or deceptive advertising and marketing practices, giving money to charitable causes, responding quickly to customer problems, and avoiding polluting the environment, among many other methods.

Specific company examples of robust CSR activities include:

- LEGO’s pledge to reduce its carbon impact: LEGO is the first and only toy company to be named a World Wildlife Fund Climate Savers Partner (lego.com).

- Salesforce’s 1-1-1 philanthropic model: Beyond being a leader in the technology space, cloud-based software giant Salesforce is a trailblazer in corporate philanthropy. Since its outset, the company has championed its 1-1-1 philanthropic model, which involves giving one percent of product, one percent of equity, and one percent of employees’ time to communities and the nonprofit sector (salesforce.com).

- Ben & Jerry’s social mission: At Ben & Jerry’s, positively impacting society is just as important as producing premium ice cream. As part of its overarching commitment to leading with progressive values, the ice cream maker established the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation in 1985, an organization dedicated to supporting grassroots movements that drive social change (benjerry.com).

- Starbucks’s commitment to ethical sourcing: Starbucks launched its first corporate social responsibility report in 2002 with the goal of becoming as well known for its CSR initiatives as for its products. One of the ways the brand has fulfilled this goal is through ethical sourcing. In 2015, Starbucks verified that 99 percent of its coffee supply chain is ethically sourced, and it seeks to boost that figure to 100 percent through continued efforts and partnerships with local coffee farmers and organizations (starbucks.com).

The different corporate responsibilities that business has are illustrated in the CSR pyramid in figure 10.10.

If you were to visualize CSR strategy as a hierarchy of different social responsibilities, the foundation would be composed of legal and regulatory compliance. All companies need to obey laws and regulations as the minimum social responsibility. While this sounds banal and obvious, the copious amount of ethics scandals shows that this is not always the case. Some companies may be able to disobey laws and regulations, pay a fine, and go on to recover their market share. On the other hand, lawsuits can bankrupt a business. Either way, customers want to do business with companies that obey all applicable laws and regulations.

The second level in the hierarchy of social responsibility of corporations is an economic and financial responsibility to the firm’s owners, shareholders, and other stakeholders. Without being financially healthy and without continuously generating profits, a company is not viable, disappearing from the market. A company cannot create social good without being profitable.

The third level of social responsibility is being ethical. This goes beyond legal and regulatory compliance and is driven by robust voluntary corporate ethics programs, ethical culture, ethical leadership, and robust corporate governance.

The fourth level of the CSR pyramid is the social responsibility of being a good corporate citizen. This encompasses the firm’s social responsibility to give back to society through strategic philanthropy and to give back to the local and global communities with which the firm interacts. This level balances the firm’s financial performance with its environmental and social impact in the framework of a holistic approach to business that considers the needs of all stakeholders, not just shareholders.

CSR evolved over time and is now characterized by an integrated and transforming approach to CSR strategy. The strategic intent of CSR is value creation and social change rather than just legal and regulatory compliance. CSR is not just outsourced to a team or specialists in the organization; CSR is owned and driven by strategic leaders and managers with the support of business unit managers. It embraces a multi-stakeholder approach with partnership alliances, and it provides a high level of transparency through a full disclosure of CSR performance in specific CSR reports that the organization publishes on a regular basis. CSR went from something extra or even a greenwashing endeavor to a fully integrated strategy that is part of an organization’s culture, policies, operations, and strategy.

Video 10.1: Business Ethics: Corporate Social Responsibility [02:57]

The video for this lesson further explains corporate social responsibility.

Video 10.2: Insight: Ideas for Change—Michael Porter—Creating Shared Value [14:10]

The video for this lesson focuses on the differences between CSR and creating shared values (CSV).

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is the idea that a business has a responsibility to the society in which it operates. CSR is an approach where a company operates in ways that enhance society and the environment while pursuing its profit goal. CSR strategy as a hierarchy of different social responsibilities, including legal and regulatory responsibility, economic and financial responsibility, ethical responsibility, and corporate responsibility.

The social contract between society and business has changed. Companies are expected to assume much broader responsibilities in support of positive societal and environmental outcomes than ever before. As a result, companies are repositioning their business purposes in support of making a positive difference in the world instead of being motivated by profit alone. Stakeholders support companies that assume broader social responsibilities, which drives the positive correlation between doing something good for the planet and for people while increasing profits at the same time. Corporate social responsibility starts with the foundation of companies being compliant with all applicable laws and regulations while also acting economically and financially responsible to the firm’s owners, shareholders, and other stakeholders. Beyond that, companies are expected to be ethical, give back to society, and be good corporate citizens. Subsequently, strategic management is unsuccessful if it is performed in an ethical vacuum. An authentic and genuine commitment to CSR is rewarded by stakeholders and makes CSR a driver of value creation in the form of competitive differentiation that is business driven and stakeholder supported.

Bibliography

Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11), 1304–1320.

Carroll, A. B. (1991, July–August). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional, conceptual model of corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Cragg, W., Schwartz, M. S., & Weitzner, D. (2016). Corporate social responsibility. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315259222

Esty, D. C., & Winston, A. C. (2006). Green to gold: How smart companies use environmental strategy to innovate, create value, and build competitive advantage. Wiley.

Guerrero Medina, C. A., Martínez-Fiestas, M., Casado Aranda, L. A., & Sánchez-Fernández, J. (2021). Is it an error to communicate CSR Strategies? Neural differences among consumers when processing CSR messages. Journal of Business Research, 126, 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.044

Heal, G. (2008). When principles pay: Corporate social responsibility and the bottom line. Columbia Business School.

Haerens, M., & Zott, L. M. (2014). Corporate social responsibility. Greenhaven Press.

Henriques, A., & Richardson, J. (2004). The triple bottom line, does it all add up?: Assessing the sustainability of business and CSR. Earthscan Publications.

Hong, H., & Shore, E. P. (2022). Corporate social responsibility. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Jayachandran, S., Kalaignanam, K., & Eilert, M. (2013). Product and environmental social performance: Varying effects on firm performance. Strategic Management Journal 34(10), 1255–1264.

Lenssen, G., Perrini, F., Tencati, A., & Lacy, P. (2007). Corporate responsibility and strategic management (1st ed.). Emerald Group Publishing.

Levi’s. (n.d.). Our values: Sustainability statement. https://www.levi.com/US/en_US/features/our-values

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006, December). Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 80–92.

Study.com. (2013, December 31). Business Ethics: Corporate Social Responsibility. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xoE8XlcDUI8

Tariq, T., Farhan, H. M., & Rafique, A. (2024). Developing blueprints for sustainable excellence: The integration of green intellectual capital, green transformative leadership, entrepreneurial orientation, and cost leadership strategy. Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.52131/pjhss.2024.v12i2.2275

Wang, T., & Bansal, P. (2012). Social responsibility in new ventures: Profiting from a long-term orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 33(10), 1135–1153.

World Economic Forum. (2012, September 6). Insight: Ideas for Change - Michael Porter - Creating Shared Value. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xuG-1wYHOjY

10.7 Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG): A Sustainability Strategy

An organization’s sustainability practices are typically analyzed against environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics. Sustainability has environmental, social, and economic perspectives. In addressing sustainability challenges, almost all companies develop environmental, social, and governance strategy.

Although CSR strategy still holds relevance and importance, ESG has emerged as the leading concept for achieving or maintaining a sustainable and ethical organization. ESG has become a success-critical strategy element. ESG focuses on a company’s environmental performance, its support of social topics, such as social justice and human rights, and its corporate governance. Sometimes ESG is called “CSR with teeth” because ESG is more heavily regulated than CSR. There are far-reaching ESG disclosure and reporting requirements for companies that are not found under the CSR model. In the European Union, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) requires around 50,000 companies to report and disclose their environmental, social, and governance performances through audit-grade reporting. There is also a high level of transparency with ESG reports, and ESG ratings must meet formal transparency standards.

Stakeholders such as institutional investors place high importance on a company’s ESG performance. According to a PWC study:

- Eighty-three percent of consumers think companies should be actively shaping ESG best practices.

- Ninety-one percent of business leaders believe their company has a responsibility to act on ESG issues.

- Eighty-six percent of employees prefer to work for a company that cares about the same issues they do.

- More than 50 percent of all investments will be ESG-driven in the near future.

The large majority of investors believe that strong ESG practices can lead to better long-term returns (Deloitte Survey, 2023; Morgan Stanley Survey, 2024). Achievement of sustainability goals was the most cited business priority, identified by 75 percent of organizations as one of their five most important initiatives, well ahead of second-place digital transformation Initiatives at 56 percent (Honeywell study, 2023).

ESG strategy is a driver for value creation. The ESG-driven sustainable business transformation is collaborative, with various stakeholders like suppliers included along the value chain. A company defines its ESG strategy in support of its mission, purpose, vision, and values.

ESG is embedded in business-level strategy and contains the following strategic pillars.

- Environmental pillar: Addresses resource, land, and water use. Promotes a reduction of carbon emissions, pollution, and waste, the decarbonization of a firm’s business model, and biodiversity. Is aligned with the circular economy.

- Social pillar: Addresses labor management. Promotes the health and safety of employees, human capital development and talent management, supply chain labor standards for workers in the global value chain, social justice, consumer rights, product safety, privacy and data security, and the rights of communities affected by the business.

- Governance pillar: Promotes corporate business ethics, codes of conduct, advisory board oversight, tax transparency, anti-corruption and anti-bribery policies, and executive pay.

Environmental Pillar

The decarbonization of a company’s business model is the most critical element in fighting climate change and often the main element of the ESG environmental pillar. Companies need to define their journeys to become carbon-neutral by 2050 at the latest. As a consequence, companies are currently transparently assessing and measuring their emissions as the baseline for defining specific programs to reduce carbon emissions along their complete value chains. This is covered under corporate decarbonization strategy, which is a part of an overall sustainability strategy and includes measures like energy efficiency projects, the use of renewable energy, electrification, the use of life cycle assessments (LCA) to reduce the environmental impact of products, and partnerships with suppliers.

Another important and strategy-changing environmental element of ESG is the transformation to a circular economy. This contrasts with the current linear economy and linear business model, which follow a take-make-waste approach where resources are used to make products that are being consumed and then wasted.

Other important elements of the environmental pillar are the reduction of pollution and waste, responsible management of water, support of biodiversity, reduction of land use, opportunities in green building, renewable energy, and investment in green technology.

Social Pillar

The next pillar of ESG is the social pillar, which is related to the company’s impact on social issues and human rights. The social pillar focuses on the firm’s positive impact on different stakeholders.

The first stakeholder group is the firm’s own employees. The firm should create safe working conditions, provide appropriate compensation and development opportunities, support the continuous upskilling of its workforce, allow unionization, and have robust anti-discrimination and equal opportunity policies in place.

One success-critical element of the social pillar is the continued talent development of the firm’s workforce in the era of AI. AI, automation, and robotics are changing the way we live and the way we work. There are estimates that forecast that up to 40 percent of current jobs will disappear by 2030. Many employees will also work in jobs and positions in the future that don’t even exist today. Job families will rise and decline in the context of the transformation of industries and business models. This often requires fundamentally different and new skill sets for employees and new ways to organize work. Hence, the continued upskilling and reskilling of a company’s workforce is one of the success-critical elements of the social pillar.

Another important topic for a firm’s own workforce is the topic of “new work.” This concept encompasses all changes to work design initiated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Employees worked from home, and many continue to expect some kind of balance between in-office work and working from home. At the same time, many companies have requested employees to return full time to their offices. New hybrid work models are important challenges and critical success factors regarding a firm’s own workforce under the social pillar of ESG. Figure 10.14 shows some of the topics that are currently discussed with a high priority.

The second stakeholder group in the social pillar is workers in the firm’s global value chain. This element of ESG drives a significant paradigm change in business. The social responsibility of companies does not end at their factory gates or at borders. Firms are responsible for labor standards of workers in their global value chains. This means that companies assume responsibility for the working conditions, safety standards, work hours, and payment of workers who work for their suppliers abroad. This is a significant paradigm change that is accompanied by management and reporting challenges. Supply chain standards in global value chains need to be managed thoroughly, and companies must manage responsible sourcing practices with all of their suppliers, including auditing the human rights of their suppliers’ workers.

The third stakeholder group are communities affected by the firm’s business operations. The firm needs to respect the rights of local communities affected by the company’s operations and must provide remedies for any adverse impact of their operations.

The last stakeholder group are the firm’s consumers and end users who have the right to safe products, the absence of misleading marketing information, and especially important in the era of big data, privacy rights (for example, data protection and cybersecurity).

Patagonia, Inc., is an American retailer of outdoor recreation clothing, equipment, and food. It was founded by Yvon Chouinard in 1973 and is based in Ventura, California. Patagonia’s revenue is estimated at $1.5 billion, and the company has shown strong growth and robust success over time. However, the driver of this success is not just its high-quality products. The main differentiator and the source of Patagonia’s competitive advantage is its sustainable business model and its focus on its environmental, social, and governance performance, which is the core of ESG and CSR strategy. This is rewarded by key stakeholders like customers, who respond with brand loyalty and a higher willingness to pay for Patagonia’s sustainable products.

The company has three pillars—environmental programs, social programs, and business conduct—that follow the ESG structure. Patagonia explicitly addresses climate change in declaring “The climate crisis is our business.” Patagonia is radically reducing its carbon emissions and is transforming how they make products, using materials that cause less harm to the environment. Patagonia’s commitment goes beyond its own company and includes a goal to make a positive impact along the full global value chain, from suppliers to customers, which is one of the best practices for a robust ESG strategy.

Since 1985, Patagonia has pledged 1 percent of sales to the preservation and restoration of the natural environment. The firm awarded over $140 million in cash and in-kind donations to domestic and international grassroots environmental groups making a difference in their local communities. This is an example of strategic philanthropy, which is part of the CSR pyramid and part of the social ESG pillar.

Patagonia is a certified B Corp. Becoming a B Corp is another trend in sustainable business strategy. In business, a B Corporation is a for-profit corporation certified by B Lab, a global nonprofit organization. The certification is granted based on an assessment of a firm’s social and environmental performance.

Lastly, Patagonia is committed to the reuse and recycling of its products. Patagonia is letting go of virgin materials in support of post-consumer recycling, which refers to any finished product that has been used and then diverted from landfills at the end of its life. Patagonia ran an iconic marketing campaign in the form of a full-page advertisement in The New York Times discouraging customers from purchasing one of their jackets.

Patagonia stated in this advertisement that producing the jacket generated waste in an amount equivalent to two-thirds of the jacket’s weight. This included thirty-six gallons of water, which is the equivalent to fulfilling the daily needs of forty-five people, and twenty pounds of carbon dioxide emissions, which is twenty-four times the weight of the jacket. The advertisement ended with the plea: “Don’t buy what you don’t need.” This is an excellent example of Patagonia, like many other firms, moving from a linear to a circular economy to protect the planet’s scarce resources. A linear economy takes, makes, uses, and then wastes resources. Embracing the principles of the circular economy is an important element of the environmental pillar of ESG strategy. This replaces the linear economy with elements of reusing materials, repairing products, prolonging the product life cycle, refurbishing and remanufacturing, and recycling.

Governance Pillar

Corporate governance is the system of rules, practices, and processes by which a company is directed, managed, and controlled. The system guides a company’s relationships with its shareholders and stakeholders. Establishing and implementing these rules and practices involves balancing the interests of a company’s many stakeholders. Creating and implementing transparent rules and controls can guide leadership in aligning the interests of shareholders, directors, management, community members, and employees. Good corporate governance can benefit various stakeholders as well as the operations and reputation of a company. Bad corporate governance can destroy a company’s operations and ultimate profitability.

In large companies, a company’s board of directors is responsible for the direction and execution of the company’s corporate governance. The company’s shareholders appoint the directors to make sure that the organization has an appropriate governance structure in place.

An effective board plays a key role in various areas that are critical to an organization. Here are some of their roles:

- Appointment of corporate officers, including the CEO

- Executive compensation

- Setting company goals and approval of financial objectives

- Strategic leadership and oversight, including advising on strategic issues

- Ensuring internal controls are adequate

- Representation of shareholders and other stakeholders who have an interest in the long-term performance of the firm

- Ensuring legal compliance

- Business ethics and conduct, including anti-corruption and anti-bribery policies and tax transparency

- Providing external perspective, best practices from other industries, resources, and networking and strategic partnership opportunities, as board members are often senior executives in other companies

One of the most important roles and responsibilities of the board of directors is the representation of shareholder interest in the company. Corporate governance addresses the separation of ownership and control. Shareholders are the owners of the company, but it is not possible for individual shareholders who lack a large percentage of overall shares to have meaningful and reasonable oversight of how the company is managed by the CEO and other company officers. Hence, dispersed shareholders need a voice to speak for them and their interest—the board of directors.

A specific issue that requires robust corporate governance is conflict of interest. A company employee could possibly choose personal gain over duties to shareholders and could possibly abuse the position in the company for personal gain. This can happen when a person could receive personal benefit from decisions being made by a company employee in their official capacity. For example, a procurement manager has been tasked with identifying the best supplier to provide maintenance services for the company’s car fleet. One of the possible suppliers is owned by his brother-in-law, who would be happy to gain this significant business. However, the company operated by him does not provide the best offer in terms of quality and price for the organization that buys the maintenance services. The company’s procurement manager may have two conflicting interests. In his capacity as a professional procurement manager, he needs and wants to give the business to the most suitable supplier, which is not his brother-in-law’s business. On the other hand, he would love to help his brother-in-law, his sister, and their family to do well and gain the business. Obviously, the decision to give the business to the procurement manager’s brother-in-law is not in the interest of shareholders. Corporate governance needs to address conflict of interest issue and provide some clear policies and guidance.

Another example is a CEO who pursues the acquisition of a competitor and who is willing to spend too much money on the acquisition. The reasons for the CEO’s willingness to overpay for the acquisition may be personal interest in gaining power and reputation, leading a larger company, and possibly receiving higher compensation for leading the larger company. This would be a conflict of interest in regards to what is best for shareholders compared to the CEO’s own personal ambitions.

The disconnect between the interests of the employees, manager, and CEO in the above examples and the interests of the owners (the shareholders), are described as the principal-agent problem or agency problem. The principal-agent problem is a conflict in priorities between a principal, here the shareholders, and the agent authorized to act on their behalf, company employees and especially leadership. An agent may act in a way that is contrary to the best interests of the principal.

The role of corporate governance is to identify and address possible conflicts of interest and possible principal-agent problems. This could be achieved by providing clear guidance on how possible conflicts of interest need to be handled in the company’s code of conduct.

Generally, the basic principles of good corporate governance are as follows.

- Accountability: The board must explain the purpose of a company’s activities and the results of its conduct. Both board and company leadership are accountable for the assessment of a company’s capacity, potential, and performance. It must communicate issues of importance to shareholders.

- Transparency: The board should provide timely, accurate, and clear information to all stakeholders.

- Fairness: The board of directors must treat shareholders, employees, vendors, and communities fairly and with equal consideration.

- Responsibility: The board is responsible for the oversight of corporate matters and management activities. It must be aware of and support the successful ongoing performance of the company. Part of its responsibility is to recruit and hire a CEO. It must act in the best interests of a company and its investors.

- Risk management: The board and management must determine risks of all kinds to shareholders and other stakeholders. It must provide guidance on how best to control and mitigate risks. It must act on those recommendations to manage risks and inform all relevant parties about the existence and status of risks.

The benefits of good corporate governance include building trust with investors, the community, and public officials. Good corporate governance helps an organization to operate more efficiently, and it promotes the long-term financial viability of the organization. It helps organizations to respond to stakeholder concerns swiftly and effectively. It improves access to capital, improves a company’s reputation and reduces the risk of business ethics violations. Finally, good corporate governance safeguards against mismanagement and the potential for financial loss.

Bad corporate governance can have the opposite effect, eroding relationships and trust with both internal and external stakeholders. This can damage a company’s reputation, create legal, regulatory, or ethical scandals, reduce both employee and customer retention, cause stock prices to fall, and ultimately eat away at a company’s profitability.

Corporate governance, particularly the role of boards of directors, has long been critiqued for its relative ineffectiveness in safeguarding ethical business conduct and ensuring long-term value creation. Boards are meant to provide oversight, ensure accountability, and represent shareholders’ interests, yet several inherent weaknesses often limit their effectiveness.

One primary critique is the problem of insufficient independence between board and firm. Many boards are composed of directors with close personal or professional ties to the CEO or other executives, leading to conflicts of interest and a lack of genuine oversight. This dynamic can result in management decisions being “rubber-stamped” rather than challenged, especially on ethical or controversial issues. Another criticism is the lack of broad perspective in expertise, perspective, and background among board members, which can narrow the scope of strategic discussions and blind boards to emerging risks, particularly around social, environmental, and ethical concerns.

Additionally, the infrequency of meetings and the often-superficial nature of board deliberations can prevent directors from fully understanding complex business operations and risks.

Ethical failures often stem from boards prioritizing short-term financial performance over long-term sustainability and ethical considerations, pressured by shareholder expectations or executive incentives tied to stock performance. This can lead to a focus on profit at the expense of social responsibility, environmental stewardship, or sound governance, undermining the board’s fiduciary duty to broader stakeholder groups.

Some of the most recent trends and hot topics in corporate governance are:

- Board composition with a broad background

- Executive compensation

- Making ESG an imperative

- Dealing with more conscientious consumers, with millennials and Gen-Z leading the change

- Ensuring boards are a strategic asset

- A focus on future-proofing companies in the face of disruptive change

- Companies implementing new technologies like AI in a responsible way using robust and meaningful data governance policies

CEO compensation and excessive retirement packages and severance agreements are issues in corporate America, where they are sometimes called “golden handshakes.” CEO-to-worker compensation has reached a multiple of around 350 in the U.S., a huge increase from a ratio of around forty until the 1980s and much higher than ratios in other countries and regions of the world. Obviously, it is not possible to determine a perfect ratio and the appropriate compensation for senior executives, which is a very complex, multifactor decision. The notion of self-serving executives is a criticism raised by stakeholders in the U.S. CEO compensation is the result of supply and demand, and executive leaders bring unique competencies and experience into the equation. However, excessive ratios have seen a lot of scrutiny in the governance pillar for assessing a company’s ESG performance.

Video 10.3: Role of the Board in Creating an Ethical Corporate Culture [06:48]

The video for this lesson describes the role of the board in creating an ethical corporate culture.

Application

- Choose your favorite company or your preferred future employer. Visit the company’s website, and explore the company’s ESG strategy.

- What are the specific initiatives and actions that the company takes in support of environmental and social issues?

- How does the company measure its performance?

- Which metrics and KPIs are being used?

- How does the company report on its ESG activities and ESG performance?

An organization’s sustainability practices are typically analyzed against environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics. Sustainability has an environmental, social, and economic scope. In response to addressing sustainability challenges, almost all companies develop ESG strategy.

A company must embed sustainability into the fabric of its business, corporate culture, and corporate strategy. A robust ESG strategy is the core of a company’s sustainability strategy, which enables new business models to support sustainability goals, increases operational efficiencies, complies with regulatory requirements, exposes innovation opportunities, and improves the customer experience while creating competitive advantage. Success-critical areas of ESG include the design of transparent and resilient global supply chains that embed ethical and sustainable practices and that support a circular supply chain. Firms must embark on transparent and high-quality legal and regulatory reporting that meets the demands of regulators and investors for financial-grade disclosure of ESG metrics. Firms engage with various stakeholders in the context of inclusive stakeholder management. Lastly and maybe most importantly, firms decarbonize their production and operations to manage the transition to clean energy and to map out a clearly defined path to net-zero business operations.

Bibliography

Anderson, R. C. (2009). Confessions of a radical industrialist: Profits, people, purpose—Doing business by respecting the Earth. St. Martin’s Press.

Atkins, B. (2022). The 4 eras of corporate governance. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/betsyatkins/2022/01/10/the-4-eras-of-corporate-governance

Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11), 1304–1320.

Esty, D. C., & Winston, A. C. (2006). Green to gold: How smart companies use environmental strategy to innovate, create value, and build competitive advantage. Wiley.

Gellis, D. (2021, Dec. 10). The Patagonia’s CEO’s mission: “Save the Planet.” The New York Times.

Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. (2013, November 26). Role of the Board in Creating an Ethical Corporate Culture. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kOm8SC8qI4w

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2024). Beyond compliance: Consumers and employees want business to do more on ESG. https://web.archive.org/web/20240102221025/https://www.pwc.com/us/en/services/consulting/library/consumer-intelligence-series/consumer-and-employee-esg-expectations.html

10.8 Ethics Strategy

One positive outcome of corporate scandals has been an increased focus on business ethics by firms. Business ethics covers the moral principles, policies, and values that govern the way companies and individuals engage in business activity. It is a form of applied professional ethics that examines ethical principles and problems that can arise in a business environment. Business ethics applies to all aspects of business conduct and is relevant to the conduct of individuals and entire organizations. At the minimum, companies need to stay compliant with all applicable laws and regulations to avoid lawsuits and fines, and they must also avoid violating regulation that will limit the business’s freedom to act. Strategy development should always occur through acceptable practices in the industry and in light of the firm’s own code of ethics and compliance.

Corporate scandals:

- Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme: Madoff was a former chairman of the NASDAQ stock exchange and ran an investment firm that promised consistently high returns. Instead of using real investment profits, he paid earlier investors with money from newer investors, which created the illusion of success. His scheme lasted from the ’90s until its collapse in 2008, when the financial market downturn led to many clients withdrawing their money, exposing his fraud. Madoff’s scheme is considered the largest financial fraud in history.

- Volkswagen’s Dieselgate: In 2015, Volkswagen was caught in a scandal for installing illegal software and defeat devices in millions of diesel cars worldwide to cheat on their emissions tests. The software allowed the cars to pass emissions tests by temporarily lowering nitrogen oxide emissions to comply with regulations during testing. However, during regular driving, the cars emitted pollutants forty times greater than allowed, far exceeding legal limits. As a result, Volkswagen faced massive amounts of recalls, numerous legal actions, and fines, costing the company billions of dollars as well as severely damaging its reputation.

- Purdue Pharma and the U.S. opioid crisis: A pharmaceutical company founded in 1892 played a significant role in the U.S. opioid crisis by aggressively marketing OxyContin as a safe painkiller with a low addiction risk, despite a lack of evidence. Purdue’s misleading claims resulted in widespread overprescription, which led to many patients becoming dependent on the drug. As these addiction rates skyrocketed, OxyContin became extensively misused, meaning that Purdue Pharma played a huge role in the catastrophic opioid epidemic. The company then had to face numerous lawsuits, having to settle for over 4.5 billion dollars in 2021 and eventually filing for bankruptcy. The opioid crisis led to the overdose death of hundreds of thousands of victims.

- Boeing 737 Super Max airliner with two crashes: The Boeing 737 MAX was involved in two fatal crashes that resulted in 346 people losing their lives. These unfortunate crashes resulted from the malfunction in their Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, which caused the planes’ noses to be tilted down due to faulty sensor data. Investigations into the two flights exposed Boeing’s design flaws and its lack of pilot training and regulatory management by the Federal Aviation Administration. The 737 MAX fleet had to be grounded, and Boeing was met with countless lawsuits and reputational damage. The Boeing 737 MAX was able to be redeployed after software fixes and regulatory changes.

- Two million fake Wells Fargo accounts: This scandal was centered on Wells Fargo employees developing over two million unauthorized bank and credit card accounts without consent from customers, driven by extreme sales pressure to meet unrealistic quotas set by Wells Fargo Management. Customers were billed fees for these accounts, negatively affecting their credit scores and their wallets. Wells Fargo was ordered to pay $185 million and was subject to abundant lawsuits and investigations. Several Wells Fargo executives resigned, and the company was required to reform its unethical sales practices and corporate culture.

- Theranos case: Elizabeth Holmes founded Theranos in 2003, claiming its technology could change blood testing forever by only requiring a couple drops of blood. The company raised over $700 million, reaching a $9 billion valuation. However, in 2015, investigations showed that Theranos’s device, Edison, was unreliable and that the company was really using commercial machines for their tests. This led to lawsuits, federal charges, and the downfall of Theranos. In 2022, Holmes was convicted of defrauding investors.

As firms move from “doing right” to “doing good” and endorse ESG and CSR strategies, then employees, managers, customers, and other stakeholders take pride and satisfaction in the impact their company has on improving society. Further, as contemporary societal expectations have shifted toward companies embracing a responsibility beyond the profit motive, firms have witnessed new opportunities to turn corporate values and ethical decision-making into a competitive advantage within their marketplace.

Today, corporate business ethics goes beyond compliance and is not solely a reactive approach. Business ethics is part of an organization’s core values and corporate culture. Ethics is part of an organization’s foundation, incorporated into the organization’s business-level strategy and embedded in its daily decision-making. Failure to balance stakeholder interests can result in failure to maximize shareholders’ wealth. A robust corporate ethics strategy becomes a source of competitive differentiation and a source of sustainable competitive advantage.

Video 10.4: The ethics of business. Where and why it can go wrong [10:55]

This video explains the ethics of business and where and why it can go wrong.

Video 10.5: What is business ethics? [04:08]

The video for this lesson explains personal business ethics.

Video 10.6: What is Ethics? What is Business Ethics? [04:35]

This second video for the lesson focuses on business ethics.

Application

- Think about your own personal ethics. Describe the ways that “doing right” and “doing good” are different for you.

Business ethics covers the moral principles, policies, and values that govern the way companies and individuals engage in business activity. It is a form of applied professional ethics that examines ethical principles and problems that can arise in a business environment.

Bibliography

Agarwal, S., & Bhal, K. T. (2020). A multidimensional measure of responsible leadership: Integrating strategy and ethics. Group & Organization Management, 45(5), 637–673. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601120930140

Albeck-Ripka, L. (2020). Executives to step down after Rio Tinto destroys sacred Australian sites. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/11/business/rio-tinto-indigenous-sites.html

Carroll, A. B., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2012). Business and society: Ethics, sustainability, and shareholder management. South-Western Cengage.

Cranfield School of Management. (2010, July 13). The ethics of business. Where and why it can go wrong. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAtu_iBbknY

Global Ethics Solutions. (2019, November 1). What is business ethics? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IEmUag1ri6U

Hill, K. (2022). How Target figured out a teen girl was pregnant before her father did. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2012/02/16/how-target-figured-out-a-teen-girl-was-pregnant-before-her-father-did

Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. (2010, October 1). What is Ethics? What is Business Ethics? - Markkula Center for Applied Ethics [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmVu66Fpd9U

Singer, A. E. (2007). Integrating ethics with strategy: Selected papers of Alan E. Singer. World Scientific.

10.9 Contemporary Questions of Corporate Ethics

Businesses need to embrace a robust system of data governance to manage data responsibly.

For new technologies, there is clearly a regulation lag. Regulators and lawmakers struggle to grasp the ethical implications of new technologies, leading to a lack of regulation in this time of accelerating technology penetration.

At the same time, there is also an ethical lag that occurs when the speed of technological change far exceeds that of ethical development.

Consequently, ethical technological leadership is critical for businesses, which includes an appropriate level of self-regulation. The current business ethics “hot topic” is making responsible and ethical decisions as to what ethical principles will be programmed into AI and applied to machine learning. While there is no perfect solution, companies need to develop robust technology strategies and data governance strategies embedded in their ethics and CSR/ESG strategies.

Business Ethics in a Multi-Stakeholder Society and Shareholder Activism

Companies operate in an era of hyper-transparency and intensifying political and social disruptions. There are growing expectations from various stakeholders to support a more inclusive economy and sustainable environment. The U.S. has clearly moved away from a business social contract where the shareholder is the most important stakeholder and guiding star for business. We have moved away from a shareholder economy to an inclusive stakeholder economy. As a result, companies are reevaluating their purpose in society. Business assumes broader responsibilities in relation to society and serves a wider range of human values than ever before. Engagement with multiple stakeholders and the strategic management of public issues becomes critical not only for financial success but often for the survival of companies.

Another contemporary issue is the emergence and evolution of shareholder activism. Now, even smaller shareholders use their rights to position topics on the agendas of CEOs and boards of directors that go beyond financial topics. Social and environmental issues are aggressively pursued, and companies need appropriate strategies to interact with activist shareholders.