Epistemic Vulnerability and Tolerance in Society

Maddox Larson

The question of church-state separation has haunted America since her founding. James Madison and select founding fathers suggest that religions and states are better off when they minimize (or altogether eliminate) their interactions. Many Muslims in Iran, for instance, believe the opposite—aligning state functions with religious motives results in the most effective state. In this article, I propose a model of thinking about church-state separation in which states and religions must maintain epistemic vulnerability to allow legal, political, and socio-religious change. Simply put, epistemic vulnerability is an attitude of susceptibility to new sources and instances of knowledge. I present institutions as sets of constraints which interact with shared mental models. In this way, I explain how cultural institutions limit and shape individuals’ susceptibility to new knowledge. A religion being more accommodating to self-assessment when confronted with new knowledge aids in forming institutions that are reliable, efficient, and robust for groups to grow and adopt new ideas. This results in a model of state-religion relationship that highlights the impact on epistemic vulnerability when either religious organizations or state governance expand their responsibilities outside of their proper functions.

1. Introduction

Pioneer of early-American law and father of the U.S. Constitution James Madison ([1822] 1910, 102) once wrote, “I have no doubt that every new example, will succeed, as every past one has done, in shewing that religion [and government] will both exist in greater purity, the less they are mixed together.” As an authority on the matter of church-state relations (Muñoz 2003), Madison’s words ring loud 200 years after his death. During his life, Madison was regarded as a secretive man with respect to his thoughts on religious governance. Access to his personal correspondence has made his stance clearer. To Madison, the functions of the state and the motives of religion were to be kept separate for the betterment of both groups.

In the intervening years, thinkers have taken varied stances on this complex issue. The variance in answers to the question of religious governance comes, in part, due to different definitions of state authority. One’s understanding of the authority of the state shapes their willingness to allow it to align its means or ends with a religion. Marx, for example, refers to religion as a compensator for the heartlessness of the world (Surin 2013; Toscano 2010). Thus, the very presence of religion means that liberation is required for those who believe, and, per Marx’s account, this ought to be carried out by the state (Surin 2013, 10). Shī’a Muslim scholars in Iran have advocated for an Islamic state since long before the Iranian Revolution of 1979 (Tamadonfar 2022; Farmanfarma 1954). This view stems from their strong religious belief in the sovereignty of the Prophet Muhammad’s Qur’ānic writings and the universality of the sharī’ah (Islamic law).

Islam and Christianity are the most popular world religions. The Pew Research Center (2015) reports that in 2010 approximately 31% of the world population identified as Christian and 23% identified as Muslims. It is expected that the Muslim population will grow to about 30% by 2050 and the Christian population will stagnate at 31%. While the attitudes of individual religious persons vary, patterns emerge generally. Baker (2015, 399) writes that American-Christians:

[S]truggle with the sense that the nation [the United States] owes something to God. It owes him love and respect. It owes him obedience. They still fear as men of old did that God is a jealous god and that he will hold us accountable for refusing to acknowledge his blessings and for flouting his law. They want to save souls, yes, but they also want to bring the nation back to him as they suppose it once hewed more tightly to the Father.

While this contrasts sharply with Madison’s view, it has become a staple of the modern American political sphere.

Intuitively, the interdisciplinary nature of the issue of church-state relations has yielded varied results in myriad disciplines. Political scientists, historians, sociologists, and economists have all sought to provide a perspective from their respective disciplines. Approaches from political scientists focus on religion’s impact on public policy responses to cultural issues and other political outcomes such as general elections (Greenawalt 2001; Horwitz 2008; Minkenberg 2002). Economic perspectives focus on the ways in which culture and religion affect economic outcomes such as GDP and economic growth (Guiso et al. 2006; McCleary and Barro 2006) as well as public finance outcomes (Kuran 1994).

Within political economy, Gill (2021) works considers the institutional durability of religion while Zelekha et al. (2014) identify a connection between certain religions and economic entrepreneurship. Limited philosophical works, such as the work of Guyer (2018), have provided grounding for arguments in support of religious liberty. However, no such literature has taken into account the psychological (specifically epistemic) consequences of varied forms of state-religion alignment.

To add to existing literature on church-state separation and state-religion interaction, I offer a psychological model of state-religion interaction which utilizes literature from multiple disciplines to develop a holistic approach. This approach expands on the tension between religions and state governance beyond the simple informal and formal distinction because it offers a micro-foundational approach toward the psychology of human interaction to define the interaction between these two categories.

The term “epistemic vulnerability” (Gilson 2011) is an important part of understanding how “shared mental models” (Denzau and North 1994) work to resist or embrace change. The more accommodating a religion is to self-assessment when confronted with new knowledge aids in forming institutions that are reliable, efficient, and robust for groups to grow and adopt new ideas. This results in a model of state-religion that highlights the impact on epistemic vulnerability when either religious organizations or state governance expand their responsibilities outside of their proper functions.

Section 2 defines states and religions as formal and informal institutions, respectively, using the framework provided by Douglass North and explain how institutions can affect mental models. Section 3 identifies previous attempts to define epistemic vulnerability and, expanding on Erinn Gilson’s account, further clarifies the role of tolerance in an individual’s epistemic self-assessment. Finally, Section 4 models state-religion interactions in a two-by-two matrix and explains the development of entrenched, captured, and malleable states and concludes with implications.

2. States and Religions as Institutions

In order to engage in a philosophically rigorous discussion of the consequences of state-religion alignment, I must first define what I mean by the terms ‘state’ and ‘religion’. After all, each term takes on different denotations in different discipline and I hope to offer an interdisciplinary approach. This section will provide an overview of existing definitions of states and of religions. Specifically, using Douglass North’s definition of institutions, I define religions as informal institutions and states as formal institutions. This disambiguates our terminology before entering into a discussion of the ways that institutions affect mental models.

Jonathan Smith (1998, 281) writes:

It was once a tactic of students of religion to cite the appendix of James H. Leuba’s Psychological Study of Religion (1912), which lists more than fifty definitions of religion… The moral of Leuba is not that religion cannot be defined, but that it can be defined, with greater or lesser success, more than fifty ways.

Further, some refer to religions as systems that generate certain social goods based on supernatural assumptions (Stark and Bainbridge 1980, 125). This definition, however, yields a certain degree of reductionism. The same problem exists when trying to define states (or governments). Each example that one can identify behaves in idiosyncratically different ways that creates difficulty when trying to generalize—in part due to the diverse array of political philosophies at play within these state structures.

I refer to each of the aforementioned structures—states and religions—as institutions. In Douglass North’s seminal account of institutions, North (1991, 97-98) writes:

Institutions are the humanly devised constraints that structure economic and social interaction. They consist of both informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights) … institutions reduce transaction and production costs per exchange so that the potential gains from trade are realizable.

Demarcating informal institutions from formal ones affords insight into human-institution interaction and comparative institutional structure. Variance in the degree of formality of constraints bifurcates human interactions into two categories: public (constrained by formal rules) and private (constrained by informal sanctions). North (1986, 231) also identifies organizations: “Within this institutional framework, individuals form organizations in order to capture gains arising from specialization and division.”

North helps sort religions within this taxonomy: “In the absence of a state that enforced contracts, religious precepts usually imposed standards of conduct on the players” (North 1991, 99). Stark and Bainbridge (1980, 123) explain this social phenomenon by defining religion as “systems of general compensators based on supernatural assumptions.” Psychological reasoning furthers North’s conception if one considers that religions exist to provide “existential resources”—e.g., love, community, and/or a meaning for life (Ballard 2017). I consolidate these approaches and consider religions to be the informal, humanly devised constraints and rules that provide existential resources for their members and are based on supernatural assumptions.

In order to consider how religions interact with individuals, norms and customs must be considered. Cristina Bicchieri’s Norms in the Wild (2017) is among the most recognized recent accounts of norms. While customs are behavioral patterns that individuals prefer to conform to because they meet a need (Bicchieri 2017, 15 and 35), a social norm is a rule of behavior that “individuals prefer to conform to … on condition that they believe that (a) most people in their reference network conform to it (empirical expectation), and (b) that most people in their reference network believe they ought to conform to it (normative expectation).”

Using their spiritual texts for guidance, religions are able to create behavioral rules (norms), which are enforced at three levels: the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and institutional levels. For example, the Jewish faith maintains specific dietary restrictions in accordance with their scriptures (Leviticus 11). A norm is created that members of the faith should abide by these rules and subsequent empirical and normative expectations form over time as faith members adhere to the rules. This rule is enforced (i) intrapersonally in so far as individuals hold themselves accountable for their norm violation, (ii) interpersonally when congregation members seek to hold others accountable (typically in the form of taboos), and (iii) institutionally if Jewish faith leaders (e.g., rabbis) were to hold a constituent accountable for their violation.

My model would be for naught if I were not to account for the existence of formal religious organizations. Though religions in and of themselves operate informally, it is not unheard of for their members to create formal organizations in order to further their values or beliefs. The religious people are able to exercise both informal constraints and formal constraints on their members. One of the clearest and most well-known examples of this is the Roman Catholic Church.

The Magisterium and Holy See were established to oversee the functioning of the religion in a very formal sense. The Magisterium refers to the authority vested in the Bishop of Rome (the Pope) and other bishops in communion (or aligned) with him and is responsible for scriptural interpretation (Catechism of the Catholic Church, ¶85, 100). The Holy See is the administrative body that governs the Catholic Church and, supervised by the Pope, makes decisions relating to Catholic faith and morality.

For example, the Holy See has issued the Catechism of the Catholic Church which contains all the official Roman-Catholic theological positions on a diverse array of issues. Through the creation and enforcement of the official Catholic doctrine, the Roman Catholic Church maintains both informal and formal characteristics. Doctrine and theology are still enforced at the parish and reference network levels. The Roman Catholic Church is simply a formal extension of the informal religious institution.

A religion is the collection of institutions, and the organizations which arise from such. The institution is the rules, and the organization is the rule enforcer. This further clarifies the role of the Catholic Church: the Catechism and Canon Law are the institution, and the Holy See is the organization.

Contrary to religions, states are formal institutions that use their constraints to create and maintain social, political, and economic order. As societies expand, they reach a point where “[they] need effective, impersonal contract enforcement, because personal ties, voluntaristic constraints, and ostracism are no longer effective as more complex and impersonal forms of exchange emerge” (North 1991, 100). As communities grow, they need impersonal mediation and clear and consistent rule enforcement in order to structure political, economic, and social interactions and make gains from trade realizable. States are created for precisely this purpose. States structure interactions by creating a universal set of rules by which all constituents must abide lest they face formal constraints.

The ambiguity of this conception of states allows for a plethora of interpretations, which is how different political theories and economic systems emerge. Lawson and Clark (2010) build on this understanding of states through analysis of what they call the “Hayek-Friedman hypothesis.” They derive this understanding from the works of Friedrich von Hayek and Milton Friedman that attempt to reconcile the relationship between economic theory and political philosophy at play to answer whether or not economic freedom precedes political freedom or vice versa.

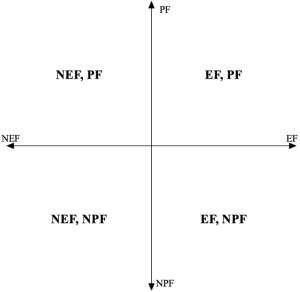

This consideration implies that the relationship of different states to each other can be understood through a simple illustration using a Cartesian graph. In Figure 1, the x-axis shows economic freedom and the y-axis shows political freedom. A point in the first quadrant would denote a state that is both politically and economically free, while a point in the third quadrant would represent a state that is neither politically nor economically free.

Insofar as states structure social, political, and economic interactions, they organize themselves in myriad ways. States often separate into multiple branches, divisions, and departments to accomplish their varied goals (consider the United States, United Kingdom, Mexico, China, etc.). All state variations in this respect can be represented on Figure 1. States represented by points further in the positive direction on the political freedom (PF) axis allow for more political freedoms such as press, association, religion, speech, etc. States further in the positive direction on the economic freedom (EF) axis allow for private property rights, market privatization, etc.

It is commonplace for the state to be regarded as an organization, body, or entity that has a monopoly on violence—or the legitimate use of force.[1] This differs from how I have regarded states. While it is apparent that states have a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, this is not all they are. Rather, they are both the institutional and organizational structures which use their constraints to create and maintain social, political, and economic order. Not only are states the rules (institutions), but they are the rule-makers and rule-enforcers (organizations). Yes, one such means of enforcement is physical violence.

Institutions create markets. In economics, markets describe the structured socioeconomic situations in which individuals are able to exchange goods and services (Herzog 2021; Rothbard 2007). Since states ipso facto structure the interactions between constituents, it follows that they structure the process by which individuals engage in commerce—in turn, creating markets. In the same way that institutions create economic markets, they can create an epistemic market of sorts where knowledge (specifically ideas and information) are traded instead of goods and services. Some have called this the “marketplace of ideas.”[2]

The role of epistemic markets is clarified by referencing knowledge that is traded in terms of general schemas (in the psychological sense). Denzau and North (1994) refer to a similar idea called “shared mental models.” On their account, these are “myths, dogmas, ideologies and ‘half-baked’ theories” which “arise in peer-based conversations … [and] that can become embedded in the institutions that shape interactions” (Denzau and North 1994, 3; Shugart et al. 2020, 371). By referencing ideological and dogmatic beliefs as ‘models,’ Denzau and North are creating a ‘cognitive bundle theory of ideas.’ We group ideas, beliefs, and knowledge together in order to more accurately describe the ‘models’ at work within particular groups and nations. Recalling the ways in which institutions structure interactions and, subsequently, create and structure economic markets, it is clear that they also create and structure epistemic markets.

3. Vulnerability and Tolerance

Recent years in American politics have seen greater degrees of polarization along political lines (Mason 2018). One consequence of polarization is its effects on information consumption. When higher degrees of polarization are present, people are less likely to evaluate mental models from individuals and organizations of similar ideological backgrounds thoroughly before adopting them. One’s ability to critically examine their mental models is crucial for their participation in a society (especially democratic societies), but also in their ability to tolerate others. Convergence toward a tolerant, pluralistic society requires epistemic vulnerability or susceptibility to new knowledge and mental models. This can only be reached through critical self-assessment.

While epistemic vulnerability is new to the literature, its presence is seen in writings on tolerance such as Locke’s A Letter Concerning Toleration and Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments. Johnson (2020) uses the term to describe a theory of epistemic obligations using Eva Kittay’s (1999) ethics of care. Sullivan et al. (2020) use epistemic vulnerability to explain the formation of varied epistemic groups based on theories of group polarization—though they leave epistemic vulnerability to be defined by the reader’s intuition. It is in her investigation of the role that ignorance plays in the endurance of oppressive systems that Erinn Gilson (2011) clearly defines epistemic vulnerability as a heightened sense of openness toward unfamiliar facts and sources of knowledge. Put another way, epistemic vulnerability is “openness to unplanned and unanticipated change” in one’s own knowledge or approach to knowledge (Gilson 2011, 313).

Gilson’s (2011, 313) argument for epistemic vulnerability arises from her opposition to its antecedent: an intentional state of ignorance because it appears to be in one’s favor to be so, called “willful ignorance.” Gilson (2011, 325) thus offers the following five criteria for epistemic vulnerability:

-

- Openness to not knowing, which is the precondition of learning.

- Openness to being wrong and venturing one’s ideas, beliefs, and feelings, nonetheless.

- Possessing the ability to put oneself in and learn from situations in which one is the unknowing, foreign, and perhaps uncomfortable party.

- Openness to the ambivalence of our emotional and bodily responses to reflecting on those responses in nuance ways.

- Openness to altering not just one’s beliefs, but oneself and sense of oneself.

Epistemic vulnerability opposes willful ignorance in specifying that the respective individual must be able and willing to put themselves in uncomfortable situations (3) and to be wrong and venture their beliefs nonetheless (2). These two criteria in particular directly oppose the willfully ignorant person’s attitude toward knowledge which contradicts or threatens to contradict their own previously acquired knowledge. While Gilson certainly offers the most complete account of epistemic vulnerability, I build off of this account to clarify the process by which the epistemically vulnerable person behaves in order to allow for a more generalizable conception. In particular, I seek to answer the following question: How does the epistemically vulnerable individual evaluate knowledge?

To maintain the same kind of vulnerability of which Gilson writes, one must recognize the different forms and sources of knowledge and the trade-offs that exist among them. Truncellito differentiates between ‘a priori’ (non-empirical) and ‘a posteriori’ (empirical) knowledge—a common bifurcation in philosophy. A priori knowledge is knowledge which can be known with reason alone, while a posteriori knowledge can be known through the utilization of the traditional human senses (experience) in addition to reason.

From these two sources, knowledge emerges in three forms: knowledge-that, knowledge-what, and knowledge-how (Hetherington). Knowledge-that (or propositional knowledge) is knowledge with the understanding “that such-and-such is so.” Examples of knowledge-that would be that Germany is a country in Europe, that water is an element represented by the chemical symbol H2O, and that B is the second letter of the English alphabet.

Knowledge-what (or knowledge-how) is representative of specific forms of knowledge-that that can be characterized by the standard “what,” “whether,” or “why” interrogatives. For example, “knowing whether it is 2 p.m.; knowing who is due to visit; knowing why a visit is needed; knowing what the visit is meant to accomplish” (Hetherington; original emphasis). Knowledge-how (or practical knowledge) is knowledge of how to do something: how to ride a bike, how to pack a suitcase, etc. (Pavese 2022).

Further, with this understanding of knowledge, we consider the evaluative process of epistemically vulnerable individuals. Specifically, we consider John Hardwig’s account of epistemic self-assessment. Hardwig (1991, 699-700) argues that in order for an individual, B, to enter into a trust-based relationship with another, A, on a particular matter, p, “B must not have a tendency to deceive herself about the extent of her knowledge, its reliability, or its applicability to whether p.” This introspective act allows one to consider their knowledge’s source and form in order to determine its scope, accuracy, reliability, and applicability to a given situation. By determining whether their knowledge is a priori or a posteriori, one must determine its accuracy and reliability.

In other words, when identifying whether a claim or belief is justified by reason alone or by senses in addition to reason, one must make a judgment of when this knowledge can be applied or if it requires additional work to justify—therefore determining its accuracy and reliability. Applicability is similarly determined by the categorization of knowledge. When one determines whether their knowledge is know-how, know-that, or know-what, they determine under what circumstances it can be used—in this case, which interrogative one might be able to answer with that form of knowledge. One’s ability to identify and categorize their own knowledge is essential to Hardwig’s account of epistemic self-assessment.

It follows that if epistemic vulnerability is a cognitive disposition to take in new information, then that one must consider knowledge’s accuracy, reliability, and applicability is a prerequisite. In order to do this, the individual must identify the knowledge’s source. Categorizing knowledge in this way requires the individual to make a judgment about its accuracy and reliability. That is, when determining whether a fact is known my reason alone or by perception, one judge’s the attributes of this fact in order to categorize it. For example, when Person A meets Person B, some of the facts about B that A will have will be reasoned from body language, speech, and other heuristics while others will be directly acquired from what B tells A. This means that in order to determine what A knows about B, they must delineate a priori judgments from a posteriori.

To perform an epistemic self-assessment is a necessary but insufficient condition of epistemic vulnerability. One cannot simply maintain an evaluative disposition when interacting with others in order to be considered “vulnerable.” The very notion of vulnerability requires more. The final, and most important, criterion of epistemic vulnerability is that which can also confront and prevent polarization: tolerance. Tolerance is not just allowing the existence or practice of beliefs/knowledge that one does not wish to partake in (Oxford English Dictionary), but also the acceptance of such behaviors or beliefs (Cambridge Dictionary).

To accept a mental model is not to approve of one. One is not after all required to approve of all behaviors which they understand that others partake in. To accept a mental model is to recognize and understand without necessarily agreeing. The epistemically vulnerable individual is tolerant by assessing their knowledge when confronted by foreign mental models, examining the mental model, and, even if the mental model is incoherent or logically invalid, the epistemically vulnerable individual tolerates these beliefs, and those that belief them, nonetheless. This toleration does not mean that society is unable to engage in critical discourse. On the contrary, epistemically vulnerable individuals discuss critically not just the seemingly incoherent and invalid mental models among themselves, but also those which seem to be the most robust. In a manner akin to Descartes and Hume, epistemically vulnerable individuals subject their knowledge to reasonable doubt in order to continually improve as societies and as a species.

4. Modeling State-Religion Interaction

To engage in a philosophical discussion, one must clearly understand all the terms at work. At this point, I have defined states as formal institutions and organizations which structure social, economic, and political interactions through the creation and enforcement of laws, penal codes, and other formal constraints. Religions are informal institutions and organizations based on supernatural assumptions which also structure social interactions, but by the generation and enforcement of customs, traditions, and norms. Mental models are the bundles of knowledge, ideas, and beliefs which arise from cultural institutions like religions and are subject to institutions. Epistemic vulnerability is a characteristic that describes those who are willing and able to carry out self-assessment of their knowledge when confronted with foreign mental models and, subsequently, maintain general susceptibility to new knowledge while being tolerant of mental models which they themselves do not adopt.

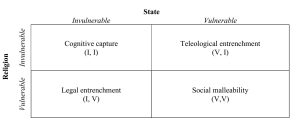

This section develops the theoretical framework to four variations in outcomes that follow from vulnerability in states and religions, each as collections of institutions and organizations. When both structures are invulnerable, there is little competition between various mental models and the incumbent group will have a monopoly or cognitive capture. Invulnerability leads to path-dependency and little growth. On the other extreme where both structures are maximally vulnerable, growth only occurs through arbitrage of existing mental models, often from the outside. I contrast the role for technological change and legal adaptation in the off-diagonals of my two-by-two matrix to show where there are meaningful trade-offs in state-religion vulnerability.

How can institutional structures be epistemically vulnerable? Recall Gilson’s (2011) five criteria of epistemic vulnerability: (1) openness to not knowing, (2) openness to being wrong, (3) putting oneself in and learning from situations in which one is the unknowing party, (4) openness to the ambivalence of our emotional and bodily responses, and (5) openness to altering not just one’s beliefs, but oneself and sense of oneself. Each of these criteria can be applied to the institutional structures we have seen by viewing the sets of rules which they utilize in their constraint of behaviors. Largely, we consider these structures to be epistemically vulnerable insofar as they allow arbitrage between mental models.

States may be epistemically vulnerable in the policies they produce and enforce. The first two criteria (openness to not knowing and to being wrong) are among the simplest for states to implement. While a state is a combination of laws, codes, and agencies, it may allow itself to be open to not knowing by failing to make claims which go beyond its scope—that is, beyond the social or political. This leaves room for cultural institutions to create additional rules for specific conduct within the private sphere of individuals’ lives.

Similarly, states can be open to being wrong by retracting legislation or regulations which have been enacted based on knowledge that the state has been shown not to have—despite past actors believing the state to have had such knowledge (also called legal change or adaptation). A state’s adherence to the fourth criterion—openness to the ambivalence of our emotional and bodily responses—will be considered its responsiveness to its member agencies. Any given policy or legislative act will have consequences for any given government agency, so openness to the responses of legislation allows a state to prevent scotosis.[3]

To a certain extent, it would be unreasonable to expect religions to maintain total epistemic vulnerability. Religions typically require the dissemination of their assumptions and conversion of other individuals. Religions exempt themselves from being maximally vulnerable for fear of, in their eyes, delegitimizing themselves. In Islam, the Qur’ān recognizes the similarity of the ontological claims of Judaism and Christianity yet draws a sharp distinction between the eschatological fate of the Muslim versus the Jew or the Christian (4:159). Christianity has similar scriptural passages to the general “unbeliever” (2 Cor. 6:13-15).

Religions must then maintain an amount of epistemic vulnerability which is efficient so as to attain the benefits of vulnerability while not incurring the costs of threatening their ontological and metaphysical claims. Unfortunately, this ambiguity is both unavoidable and required by the observer-relativity of epistemic vulnerability. This means that the religious individual’s epistemic self-assessment is different in that they must also factor in a cost-benefit analysis towards the ontological claims of their religion when attempting to maintain epistemic vulnerability.

Now, I introduce the following four variations in outcomes that follow from the epistemic vulnerability of state and religious institutions: cognitive capture, entrenchment (teleological and legal), and maximum social arbitrage. These are seen in relation to the vulnerability of the two institutions in Figure 2.[4]

On the off-diagonal, first consider an invulnerable state paired with vulnerable religion. This results in legal entrenchment. On constitutional entrenchment, Callais and Young (2022) write that a constitution is entrenched when procedural barriers make constitutional amendment more onerous than ordinary policy change. Therefore, in a scenario where religious structures are willing and able to adopt new mental models, but state structures are not, the legal system is entrenched. In this context, systemic legal change is made more onerous than religious cultural change by means of invulnerability.

Following the off-diagonal, when states are vulnerable while religions are not, society is susceptible to teleological entrenchment. Under these conditions, invulnerable religions each seek to capture (or monopolize) the epistemic marketplace and to purport their mental models while expelling all others. From their perspective, this would increase the religion’s growth. When coupled with a vulnerable state, the result is a society which is capable of political and economic change, but is held back by the over-enforcement of religious norms that will come with attempts to capture the epistemic market.

The first box along the main diagonal in Figure 2 reveals that invulnerability on the part of both state and religious structures creates cognitive capture. As alluded to previously, “cognitive capture” is the process by which an individual, group, institution, or organization attempts to monopolize the promulgation or acceptance of their mental model (Thomas 2019). Due to their invulnerability, states and religions pursue two paths under these circumstances: mutual reinforcement or exclusive enforcement. If they opt to become mutually reinforcing, the newfound “state-religion” will be able to use both informal and formal constraints to enforce rules.

This means that when an individual is faced with violation of a religious norm, for example, they face the expected informal constraints from their religious peers (e.g., taboos, ostracism, etc.) but also face formal constraints from the state. Their shared invulnerability will severely limit or entirely halt the exchange of ideas. If the two opt for exclusive enforcement, they operate separately with each imposing strict rules and consequences for violation; however, violation is limited to the sphere of formality of the institution.

Following the main diagonal, as indicated in Figure 2, social malleability is the opposite of cognitive capture. Wherein a cognitively captured society neither institution is susceptible to new knowledge and therefore change, both are susceptible to new knowledge and change in a socially malleable society. When each of these structures allows for maximum arbitrage between mental models, they create an epistemically open and unregulated society. Effectively, this means that mental models can be traded freely with severely limited enforcement of formal or informal constraints. In a society of pure arbitrage, constant change would be occurring which would leave no room for consistency or legitimacy of these structures to develop. While change is often good and needed, too frequent change undermines the process.

Resulting from previous discussion of the four variations of state-religion interactions, consider the subsequent optimization problem. This problem is best framed as a question: What degrees of vulnerability/invulnerability for state and religious institutions are optimal for the growth of society? The answer is simple—in theory. Convergence along the main diagonal achieves a free and flourishing society. A society of this type allows for religions to maintain a certain degree of invulnerability (as would states), while also requiring clear processes with limited barriers to change when necessary.

5. Conclusion

In order to offer an explanation for James Madison’s ([1822] 1910, 102) famous claim that both religions and states will be better off given their separation, I have provided a psychological, micro-foundational approach to explain the consequences of four variations of state-religion interaction. This approach builds on political, economic, and philosophical approaches to the notion of church-state separation. Political approaches focus on the negative outcomes of mutually reinforcing state-religions on political judgments, election results, and general policy responses (Greenawalt 2001; Horwitz 2008; Minkenberg 2002), while economic approaches focus on economic outcomes such as GDP and economic growth (Guiso et al. 2006; McCleary and Barro 2006) as well as public finance outcomes (Kuran 1994).

To unite many of these political and economic approaches, I have defined states and religions as formal and informal institutions, respectively. That is, understanding institutions as humanly devised constraints which structure various aspects of our interactions (North 1994), both states and religions set out to govern our social, political, economic, and religious interactions in different respects. Regardless of the ways in which they do this, both institutions have an effect on the exchange of ideas. Collections of ideas, knowledge, and beliefs can be called “mental models.” Each respective institution, through their own enforcement of their rules, shapes the ways in which mental models are exchanged in the epistemic marketplace.

When institutions shape epistemic exchange, they also impact individuals’ epistemic vulnerability. Epistemic vulnerability is used in the contemporary literature by Johnson (2020) as a term which describes her theory of epistemic obligations stemming from Kittay’s (1999) ethics of care and it is used by Sullivan et al. (2020) to explain the creation of various epistemic groups based on theories of group polarization. Gilson (2011) provides an account of epistemic vulnerability in response to the place of ignorance in the maintenance of oppressive systems. Gilson’s account is worthwhile in its clear provision of criteria of epistemic vulnerability. I amend her account to argue epistemic vulnerability is susceptibility to new knowledge, willingness to put oneself in uncomfortable epistemic situations, willingness and ability to critically examine one’s knowledge (self-assessment), and ability to pursue and maintain tolerance of foreign mental models.

Institutional structures (i.e., collections of institutions and organizations) can be epistemically vulnerable as well. Recall that institutions are sets of rules used to constrain behaviors. Organizations are sets of individuals who organize to realize gains from trade within a particular institutional framework. To allow arbitrage between mental models is to be epistemically vulnerable for institutional structures. And so, I introduce four variations of state-religion vulnerability: cognitive capture, teleological entrenchment, legal entrenchment, and social malleability.

A society is cognitively captured when both state and religion are invulnerable and mutually or exclusively enforce their rules in monopolistic ways. Cognitive capture results in a limited or zero-arbitrage society. When states are vulnerable and willing to support change and religions are invulnerable, teleological entrenchment occurs and religions maintain their monopolistic tendencies to capture society while states are capable and willing to carry out political and economic change. Legal entrenchment occurs when invulnerable states prevent political and economic change through increasingly onerous legal barriers, while religions are able and willing to support change. Either form of entrenchment results in little to no change in social procedures. When both are vulnerable and support change, achieving social or legal change becomes trivial, so much so that the credibility of each institution is severely limited. Too much change results in a lack of stability.

The resulting optimization problem is solved when we consider convergence from cognitive capture to social malleability. That is, optimal capacities for change are achieved by allowing states and religions certain degrees of entrenchment while maintaining epistemic vulnerability. Limited (but still present) barriers to social and legal change ensure that these processes are able to maintain checks-and-balances and proper evaluation before change is adopted. As a result, entrepreneurial and opportunistic behaviors are still encouraged such that change of any variety can occur when necessary.

Acknowledgements

This research was completed under funding through the Gail Werner-Robertson Research Fellowship in the Menard Family Institute for Economic Inquiry. The author is grateful to Creighton University Professors Michael D. Thomas, Elizabeth Cooke, and J. Patrick Murray, who provided valuable comments and insights.

References

Baker, H. (2015). Is Christian America Invented? And Why Does It Matter? Journal of Markets and Morality, 18(2), 391-400.

Ballard, B. (2017). The Rationality of Faith and the Benefits of Religion. International Journal of Philosophy of Religion, 81, 213-227. DOI 10.1007/s11153-016-9599-5.

Bicchieri, C. 2017. Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure, and Chance Social Norms. New York: Oxford University Press.

Catechism of the Catholic Church. Second edition. Washington: United States Council of Catholic Bishops, 1997.

Callais, J., and Young, A.T. (2022). Does Rigidity Matter? Constitutional Entrenchment and Growth. European Journal of Law and Economics, 53, 27-62. DOI 10.1007/s10657-021-09715-4.

Denzau, A.T., and North, D.C. (1994). Shared Mental Models: Ideologies And Institutions. Kyklos, 47(1), 3-31. DOI 10.1111/j.1467-6435.1994.tb02246.x.

Farmanfarma, A. (1954). Constitutional Law of Iran. American Journal of Comparative Law, 3(2), 241-247, https://www.jstor.org/stable/837742.

Gill, A. (2021). The Comparative Endurance and Efficiency of Religion: A Public Choice Perspective. Public Choice, 189, 313-334. DOI 10.1007/s11127-020-00842-1.

Gilson, E. (2011). Vulnerability, Ignorance, and Oppression. Hypatia, 26(2), 308-332, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23016548.

Greenawalt, K. (2001). Religion and American Political Judgments. Wake Forest Law Review, 36, 401-421.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., and Zingales, L. (2006). Does Culture Affect Economic Outcomes? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 23-48. DOI 10.1257/jep.20.2.23.

Guyer, P. (2018). Mendelssohn, Kant, and Religious Liberty. Kant-Studien, 109(2), 309-328. DOI 10.1515/kant-2018-2005.

Hardwig, J. (1991). The Role of Trust in Knowledge. Journal of Philosophy, 88(12), 693-708, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2027007.

Herzog, L. (2021). Markets. In Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford: Stanford University, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/markets/.

Hetherington, S. Knowledge. In Johnathan Matheson (ed.), Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://iep.utm.edu/knowledg/#H1.

Horwitz, P. (2008). Religion and American Politics: Three Views of the Cathedral Section II: Other Works. University of Memphis Law Review, 39(1), 973-1035.

Johnson, C.R. (2020). Epistemic Vulnerability. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 28(5), 677-691. DOI 10.1080/09672559.2020.1796030.

Kittay, E. (1999). Love’s Labor: Essays on Women, Equality, and Dependency: Thinking Gender. New York: Routledge.

Kuran, T. (1994). Religious Economics and the Economics of Religion. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 150(4), 769-775, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40751766.

Lawson, R.A., and Clark, J.R. (2010). Examining the Hayek-Friedman Hypothesis on Economic and Political Freedom. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 74, 230-239. DOI 10.1016/j.jebo.2010.03.006.

Madison, J. ([1822] 1910). Letter to Edward Livingston. In Gaillard Hunt (ed.), The Writings of James Madison, vol. 9. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 98-103, https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/madison-the-writings-of-james-madison-9-vols.

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McCleary, R.M., and Barro, R.J. (2006). Religion and Political Economy in an International Panel. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(2), 149-175, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3838311.

Minkenberg, M. (2002). Religion and Public Policy: Institutional, Cultural, and Political Impact on the Shaping of Abortion Policies in Western Democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 35(2), 221-247.

Muñoz, V.P. (2003). James Madison’s Principle of Religious Liberty. American Political Science Review, 97(1), 17-32. DOI 10.1017/S0003055403000492.

North, D.C. (1986). The New Institutional Economics. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 143(1), 230-237.

North, D.C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspective, 5(1), 97-112.

Pavese, C. (2022). Knowledge How. In Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman (eds.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/knowledge-how/.

Pew Research Center. (2015). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050, https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2015/04/02/religious-projections-2010-2050/.

Rothbard, M.N. (2007). Free Market. In David R. Henderson (ed.), Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/FreeMarket.html.

Shugart, W.F., Thomas, D.W., and Thomas, M.D. (2020). Institutional Change and the Importance of Understanding Shared Mental Models. Kyklos, 73(3), 371-391. DOI 10.1111/kykl.12245.

Smith, J.Z. (1998). Religion, Religions, Religious. In Mark C. Taylor (ed.), Critical Terms for Religious Studies, London: The University of Chicago Press, 269-284.

Stark, R., and Bainbridge, W.S. (1980). Towards a Theory of Religion: Religious Commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 19(2), 114-128, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1386246.

Sullivan, E., Sondag, M., Rutter, I., Meulemans, W., Cunnigham, S., Speckman, B., and Alfano, M. (2020). Vulnerability in Social Epistemic Networks. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 28(5), 731-753. DOI 10.1080/09672559.2020.1782562.

Surin, K. (2013). Marxism and Religion. Critical Research on Religion, 1(1), 9-14. DOI 10.1177/2050303213476107.

Tamadonfar, M. (2002). Islam, Law, and Political Control in Contemporary Iran. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(2), 205-219. DOI 10.1111/0021-8294.00051.

Thomas, M.D. (2019). Reapplying Behavioral Symmetry: Public Choice and Choice Architecture. Public Choice, 180, 11-25. DOI 10.1007/s11127-018-0537-1.

Toscano, A. (2010). Beyond Abstraction: Marx and the Critique of Religion. Historical Materialism, 18(1), 3-29. DOI 10.1163/146544609X12537556703070.

Truncellito, D.A. Epistemology. In Jonathan Matheson (ed.), Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://iep.utm.edu/knowledg/#H1.

Zelekha, Y., Avinmelech, G., and Sharabi, E. (2014). Religious Institutions and Entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 42, 747-767. DOI 10.1007/s11187-013-9496-6.

- This is credited to Max Weber in his lecture “Politics as a Vocation” (1918). ↵

- Some credit the phrase to Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas in his dissenting opinion on Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494, 584 (1951) where he writes, “When ideas compete in the market for acceptance, full and free discussion exposes the false and they gain few adherents. Full and free discussion even of ideas we hate encourages the testing of our own prejudices and preconceptions. Full and free discussion keeps a society from becoming stagnant and unprepared for the stresses and strains that work to tear all civilizations apart.” ↵

- Scotosis refers to intellectual blindness or a hardening of the mind against unwanted wisdom. ↵

- I owe Jack Johnston for helping develop this figure. ↵