Representative Randomness: The Case for a Randomly Weighted Voting System

Adam Cooper

Free and fair elections are a powerful tool of representative democracy, providing citizens with a unique opportunity to express their political ambitions. Yet, the United States’ current electoral process for federal congressional elections often leads to the selection of members of Congress who are elected only by a small portion of those eligible to vote and who are often woefully uneducated about the candidates they are voting upon. This article proposes a novel institutional reform to the United States’ federal congressional electoral process. To improve voter representation, the article argues for the institution of a randomly weighted voting system that would help achieve better democratic outcomes in federal congressional elections. The suggested voting system would increase voter turnout, involve more informed voters, select more representative politicians, and would ultimately improve the democratic autonomy of elections.

1. Introduction

The Washington Post’s chief correspondent Dan Balz (2014) once wrote: “To too many Americans, the system appears broken, rigged against them or both.” Free and fair elections are a powerful tool of representative democracy, providing citizens with a unique opportunity to express their political ambitions. Yet, the United States’ current electoral process for federal congressional elections leads to unrepresentative members of Congress who are elected by a small portion of those eligible to vote (FairVote) and who are often woefully uneducated (Glynn 2017) about the candidates they are voting upon. During midterm elections, this problem is pronounced, with voter turnout rates remaining under 50% since 1914 (FairVote). The idea of voting might be a cultural cornerstone for many Americans, but our current electoral system has placed this process in jeopardy.

Since the United States Supreme Court’s decisions in Citizens United (Lau 2019) and Samples (2012), money has played an increasingly prominent role in American elections. These two cases led to the rise of super Political Action Committees (PACs) that can contribute unlimited amounts of money to political efforts (Kreig 2012), so long as none of these efforts are coordinated with the campaigns that they are supporting (Martin 2008). Given the high correlation between money spent on political campaigns and electoral victories, political contributions have become the de facto identifier of political success in many races. Currently, “for House seats, more than 90 percent of the candidates who spend the most win” (Koerth 2018). In the words of Lawrence Lessig (2019), we have a system of “Tweedism” in which those with power (in the form of money or political capital) effectively choose which candidates voters can select.

Hyper-focused online campaign advertisements, particularly on social media platforms, have also allowed those with money to dramatically influence how their fellow citizens vote (Wong 2018). In the 2020 general election, $2.1 billion were spent on these type of advertisements (OpenSecrets). ‘The people’ might be voting for whom they want as their representatives, but not before their choices have been pre-selected by political elites and further manipulated by powerful campaign material online.

Additionally, in races where money does not predict success (eg. Jamie Harrison’s 2020 election loss to incumbent Lindsey Graham in South Carolina), the race is already so uncompetitive that it is futile to even attempt to defeat the incumbent (Kinnard 2020). Indeed, “senate races are often predetermined, with over 80 percent of incumbents reclaiming their seats since 1964” (OpenSecrets). This scarcity of competitiveness is prominent. The Cook Political Report claims that “417 of 435 congressional races were uncompetitive as of 2016” (Kleinfeld 2018).

With such a predictable system that continuously leads to suboptimal democratic outcomes, some have thought that elections might not be the best tool for choosing representatives in representative democracies. Instead, democratic theorists such as Guerrero (2014) and van Reybrouk (2013), among others, have proposed a new system, or rather have argued for reinstituting an ancient one: random selection of legislative bodies from the citizenry. Whether functioning in place of all elected bodies or in a supplementary role, randomly selected legislative bodies would be lawmakers, either completely removing or weakening the role of elected politicians in democracies.

Despite its growing popularity, sortition is fraught with many potential problems. Yet, this movement has introduced an important tool that might be used to improve the election process, rather than replace it: randomness. More specifically, the uncertainty that arises from random situations. Uncertainty is a powerful attribute of any system because it actively works against those trying to ‘game the system.’

Intuitively, uncertainty already plays an important role in our democratic procedures: uncertainty in electoral results drives voter participation (albeit insufficiently) and uncertainty in policy outcomes encourages political debate, among other things. However, uncertainty could also be used in our elections through a randomly weighted voting system.

The way elections currently function is problematic. However, this is not a judgement on whether elections per se are problematic. Rather, the way in which they currently function is democratically insufficient. Just because elections currently lead to suboptimal democratic outcomes (in terms of representativeness of those elected, etc.) does not mean they are not a viable mechanism for democratic selection. Elections are an important tool of representative democracy. They encourage participation in civic culture, function as a means of individual and group expression, supply legitimacy to those in power, and ensure government responsiveness at least during the time of elections (Victor 2018). Accordingly, randomly weighted voting best achieves the advantages of the randomness of sortition without losing the democratically important tool of elections. While gaining the benefits of randomness, this system also utilizes elections to “ensure that individuals remain a normative priority for those currently serving in government” (Jackson 2021).

With this system in place, voters would go to the polls on election day fully informed that their vote might be weighted more heavily than the normal one person, one vote. To be clear, neither voters nor campaigns would know which votes would be weighted more heavily until after the election. Once all the votes are cast, some votes would receive the weighting, others not, all on a random basis. The candidate with the most votes in total, summing both the weighted votes (‘supervotes’[1]) and non-weighted votes, would be declared the winner. Those who received the random weighting in past elections would not be disadvantaged in receiving the random weighting in subsequent elections. There would be no calculation of the vote if the election were to happen without the random weights assigned, as this might serve to undermine the system.

In considering randomness as a tool of electoral reform and not replacement, this article argues that utilizing a randomly weighted voting system would help achieve better democratic outcomes in federal congressional elections. The suggested voting system would increase voter turnout, involve more informed voters, select more representative politicians, and would ultimately improve the democratic autonomy of elections.

2. Traditional Theories of Representation

Traditional theories of representation do not adequately “ensure that individual voters remain a normative priority for those currently serving in government” (Jackson 2021). More specifically, by tracing a view of Jane Mansbridge’s (2003) models of representation, it is clear that insufficient attention is given to the equal consideration of all citizens.

Mansbridge (2003, 515) writes, “the traditional model of representation focused on the idea that during campaigns representatives made promises to constituents, which they then kept or failed [to] keep.” She refers to this type of representation as “promissory representation.” Yet, this model of representation rests upon the assumption of a “unidirectional responsiveness” (Disch 2011, 112) from representatives to constituents. Disch (2011, 100) refers to this as a “bedrock” norm, “the common-sense notion that representatives in a democratic regime should take citizen preferences as the ‘bedrock for social choice’.” Yet, it is unclear that these citizen preferences, often described in some form of Rousseau’s volonté générale (general will) exist exogenous to the institutions in which they are expressed (Jackson 2020).

Beginning in the early 1990s, as Disch notes (2011, 102), “research in public opinion and political psychology has taken what researchers call a ‘constructionist’ or ‘constructivist’ turn,” which “contends that preferences are constituted in the communication that occurs during decision making, implying that choice is as much something that institutions effect as it is something that an individual makes.” Indeed, the benchmark of “transcribing the will of the people” (Jackson 2021) that the traditional model relies upon seems highly dubious.

Mansbridge’s (2018, 517) “anticipatory representation” that is “filled with reciprocal attempts at the exercise of power and communication, much of it instigated by the representative,” is also problematic. This model does not offer a cohesive strategy to deal with the risk of “manipulation”, and accordingly lacks explanation for why politicians would engage in educative, rather than manipulative, communication.

In later work, Mansbridge (2017, 2-21) outlines a concept of “recursive representation,” arguing that we should stop thinking of the “representative’s main job as policy-making and re-conceptualize it as communicating.” Indeed, “running for election and winning is a better test of capacity to communicate than it is a test of policy expertise. A restructured division of labor, in which the elected representative did more communicating with both constituents and other legislators while the staff did more policy-crafting, would make recursive communication more possible.”

Although Mansbridge’s notion of “representative as interlocutor” which seems to be a distinct extension from her formulation of anticipatory representation, gives more consideration to the communication between constituents and representatives, there is still concern that “recursive communication” would not occur on a “genuinely equal basis.” Put simply, some citizens, whether through pressure groups, political donations, etc. have greater ability to exert influence in this relationship. Mansbridge notes of these “massive structural and political inequalities” that hinder this equality of communication.

In sum, most traditional theories of representation fail to equally consider the interests of all citizens. By focusing on “the will of the people” at large instead of individual equality, these models (i) overlook the structural conditions that contribute to the unequal consideration of citizens and (ii) provide inadequate examination of the role of individual citizens in contributing to democratic representation.

This article proposes to address directly these issues through a new voting system that introduces more uncertainty in elections than traditional voting systems, which incentivizes equal consideration of each citizen in the electoral process.

3. Equal Consideration and Randomness

3.1 Representation Through Democratic Autonomy

What seems most desirable is representation that not only maximizes communication between constituents and representatives, but also gives equal respect to each citizen in this relationship. Under this notion of representation, electoral reforms should focus on “procedures that allow us to understand ourselves as contributing equally in policymaking” (Jackson 2020) and provide us with an equal opportunity to have our preferences (however formed) taken into consideration. More specifically, Urbinati and Warren (2008, 395) classify representation as fulfilling the norm of “democratic autonomy” if “(a) individuals are morally and legally equal and (b) individuals are equally capable of autonomy with respect to citizenship—that is, conscious self-determination — all other things being equal.”

Furthermore, in order to treat citizens as equals, the quality of exchange between constituents and representatives should be dependent on “mutual education, communication, and influence,” rather than manipulation (Mansbridge 2017, 23). Although no institutional arrangement can guarantee this type of communication, aspiring to incentivize its possibility is reasonable.

Doing so might require an expansion of who and what matters in describing representation. As noted by Disch (2011, 107), “Pitkin (1967) sets the dyadic model [focusing only on those represented and representatives] aside to propose that political representation should be conceived as a “public, institutionalized arrangement,” one where representation emerges not from “any single action by any one participant, but [from] the overall structure and functioning of the system.” Although analyzing the communication between constituents and representatives is crucial in determining the democratic quality of the representation being provided, Pitkin’s conception recognizes that the entire “political environment,”[2] in which representation functions, including the political institutions, is also of upmost importance.

It is within this broader scope that Urbinati and Warren’s (2008, 395) concept of “democratic autonomy” becomes all the more important, recognizing that democratically legitimate representation not only “instantiates the principle that all affected by collective decisions should have an opportunity to influence the outcome,” but also that this opportunity is grounded in equality. With this in mind, we can examine institutional arrangements, and in the case of this article—randomly weighted voting—by analyzing if they uphold democratic autonomy or not.

To note, it seems clear that our current system of representation, and the electoral system that underlies it, does not satisfy this norm. Whether through special interest groups, political donations,[3] or gerrymandered districts, among many others,[4] citizens in the United States are not afforded equal opportunity for participation within our elections, effectively hindering the opportunity for democratically legitimate representation to occur.

The preceding discussion of representation should explicate the ideal of equality of consideration through maximized, equal, and educative communication as fundamental to legitimate representation in representative democracy. This article proceeds with the understanding that representation in representative democracy can be considered democratically legitimate if citizens enjoy “democratic autonomy” (as defined by Urbinati and Warren 2008, 395) in the “overall structure and functioning” (as established by Pitkin 1967) of the political system. Although no proposed reform will perfectly uphold this standard, reforms that improve on our current system merit at least some examination.

Considering both the voter-side and candidate-side impact of randomly weighted voting will demonstrate how the proposed system would help advance the norm of “democratic autonomy” in our electoral process.

3.2 Voter-Side Impact

The potential power afforded to each individual voter would incentivize higher voter turnout in federal congressional elections. Currently, voters’ individual power is infinitesimal in elections. As such, justifications for voting cannot rely on the instrumental value of a single vote. Instead, voting motivation often employs some vague platitude related to democracy—’voting is an opportunity for change’ or ‘vote to make your voice heard’—requiring individuals to engage in a quasi-suspension of disbelief on election day. Randomly Weighted Voting (RWV) introduces an important change to the voting calculus of each individual.

Consider Texas’ 24th Congressional District, in which Beth Van Duyne (R) beat Candace Valenzuela (D) by a margin of 4,584 votes in the 2020 election (The New York Times 2021). To give an example under the proposed system, an individual who received a supervoter weighting of 1,000x to their vote might actually be the deciding vote in this election. Now, although a voter who received the 1,000x weight might be the deciding vote in a close election, it is not clear that the expected instrumental value of an individual vote would increase substantially.[5] If a congressional district had 400,000 voters in a given election, and 10% of those voters received a 1,000x supervoter weighting, any one of the 40,000 voters who received the 1,000x weight could have been the deciding vote, in addition to the voters who did not receive the weighting. Thus, to claim that RWV significantly increases the potential instrumental value to an extent that would impact voter turnout is tenuous at best.

Yet, the preceding argument regarding the instrumental value of one’s vote is still valuable because of RWV’s impact upon the perceived, albeit actually insignificant, increase in the instrumental value of one’s vote. Indeed, there is a tendency of voters to “overestimate their own probability of being pivotal,” (Dittmann 2014, 36) and studies also have found that certain citizens (given cognitive biases, such as self-efficacy beliefs) are “prone to overestimate the impact of their actions” (Darmofal 2010, 167). Although RWV makes no mathematical difference in the voter’s calculus, perceived instrumental value may increase, and accordingly drive voter turnout.

Contrastingly, Alvin Goldman and Richard Tuck (in Brennan and Sayre-McCord 2016, 500-1) argue that this notion of “causal efficacy,” which implies that “one’s vote counts as causing the outcome if, but only if, one’s vote is pivotal — only if, one was to vote differently, the outcome would be different,” is highly questionable. Goldman and Tuck argue, “what matters in thinking about whether one’s vote might be the cause of the victory is not whether it is necessary for the outcome, but whether it is a part of what is, in the appropriate way, sufficient for it.” Accordingly, one’s vote can cause electoral victory even if that individual vote is not necessary for victory to occur. In opposition to the public choice account, “what is important is the ex-ante probability that one’s vote will be among those that are, in the appropriate way, sufficient for electoral victory.” RWV does not simply increase the instrumental value of a single vote. Rather, it increases the probability that a voter ends up in the casually determinate group of voters, in Goldman and Tuck’s view. The potential of a 1,000x weighting would dramatically increase this probability.

Indeed, “how voters behave is ultimately an empirical question. Yet, there exists no consensus” (Spenkuch 2017, 73). Building on Tuck and Goldman’s preceding argument, this article posits that what matters to citizens who choose to vote is not whether their individual vote will be decisive, but rather that the candidate they voted for will win, and thus their existence within the causally determinate group of voters.

This framing of the individual voter’s reasoning within the context of being part of the winning group of voters is not an abstract concept, but rather at the core of our current discussions surrounding elections. The 1,000x weighting is less important in terms of instrumental value, and much more crucial in terms of causal value, when considered in Goldman and Tuck’s view. RWV can thus be seen as motivating the individual within the context of participation in a group, significantly amplifying the potential for the individual to be in the winning group of voters, and ultimately empowering voter turnout.

Increased voter turnout, although important, is not the only benefit that this system would provide. Under RWV, individual voters would also be incentivized to become more educated about who they are casting their vote for.[6] Of course, further empirical work is needed to substantiate this claim, but when trusted with more agency, we can expect that the majority of voters would take their duty more seriously. With a greater potential to have their vote be part of the causally determinate group of voters, and, for example, if one voter could potentially make the difference in deciding their representative in the House, it is plausible to assume that voters would take that responsibility more seriously.

Perhaps the single voter would still vote along her party lines, but the impact on the electorate would be significant. Armed with the potential that their vote could be randomly weighted, each individual would be prepared to justify their votes — whether because their votes may have swung the election or because it had a much greater impact than others’ votes.

By providing more agency and power to each individual voter to impact the “causal relation between the preferences of an actor regarding an outcome and the outcome itself” (Nagel 1975, 29)—in this case, between vote preference and election outcome—and utilizing powerful psychological tendencies, RWV would have a significant positive impact on voters, both in terms of turnout and education, in federal congressional elections.

Importantly, these two changes are crucial in view of Urbinati and Warren’s norm of “democratic autonomy.” With increased voter turnout, candidates are forced to give more consideration to a larger subsection of the population, furthering the idea of equalizing the contribution of each citizen in influencing political outcomes. With more informed voters, the benefit to the norm of “democratic autonomy” can be regarded in two ways. First, more informed voters are able to engage in more “considered judgement” of their own interests. When voters have more knowledge about the choices they are making in an election, they exercise more autonomy—they are better able to undertake “conscious self-determination” (Urbinati and Warren 2008, 395)—in fulfilling their individual interests in the decision-making process. Second, more informed voters are better able to engage in consideration of other voters’ interests. With more information about the interests of others (ex. how climate change disproportionately impacts citizens of lower socioeconomic status), voters can give more respect to other citizens when they vote.

Both of these changes are crucial elements of the proposed system: voters themselves contribute to representation that better fulfills the norm of “democratic autonomy” under RWV.

3.3 Candidate-Side Impact

The power of RWV lies in its ability to return power to voters during elections. As such, the impact of RWV upon candidates and their campaigns is significant. Primarily, by hindering candidates’ ability to predict where their votes will come from, campaigns will be at a substantial disadvantage if they cater to a select group or only focus on their base during elections. The uncertainty that random weighting gives rise to makes it far more difficult for candidates to know how best to win (where to physically campaign, where to spend advertising money, how to appeal to their base, etc.). With this system, every voter is now afforded much more potential power, forcing candidates to appeal to a broader range of voters in hopes of better improving their odds of winning.

Currently, political activity around elections is hyper-focused in the areas, or states in the case of presidential elections, where votes ‘really matter.’ The average voter in Michigan, for example, saw a substantially larger portion of the advertisements for both candidates in the 2020 general election (MLive Media Group 2020). This targeted campaigning is similar to focused advertising campaigns from large corporations. With an incredible amount of information about consumers, large corporations are not only able to influence consumer preferences, but actually dictate them (Kuenzler 2017). This erosion of what economists generally refer to as “consumer sovereignty” (Argarwal 2018) allows large corporations much more control in the producer-consumer relationship. Similarly, politicians are often able to dictate the “tastes” of their potential voters through highly targeted advertisements. Whether through detailed geographic data about where their potential voters are most likely to reside or microtargeting, broadly defined as “a marketing strategy that uses people’s data—about what they like, who they’re connected to, what their demographics are, what they’ve purchased, and more—to segment them into small groups for content targeting” (Nott 2020), modern campaigns and super PACs have an unprecedented ability to engage in the manipulation that Mansbridge (2018, 519) cautions against. Moreover, as Robbins (2020) notes, for competitive races, “more money will be spent by the candidates…but also by those who would like to influence the outcome.” She adds that super PACs tend to spend “for more calculated effect, focusing on competitive races.” With more money dedicated to these races, more highly targeted advertisements are produced.

Yet as information about where a potential voter, or, more specifically, where electoral power, is located becomes unclear, campaigns and other political entities will have a more difficult task determining where to allocate advertising money. As will be explained in the following preliminary statistical analysis, RWV would only have an impact upon races that are decided by close margins. Since “parties and candidates do more to convince people and get them to the polls when races are closely fought” (Klarner 2015), making advertisements more difficult to target in these races (where the advertising is most likely to have an impact) will maximize the reduction in advertising efficacy, reducing opportunities for “manipulation” (Mansbridge 2018, 519). Put simply, money in politics is weaker without a sense of direction.

This notion of a weakened sense of where the candidates’ potential votes might lie, and the corresponding uncertainty about where to spend advertisement budgets, is a crucial feature of the proposed system. In this way, each individual voter is afforded more respect and consideration than under our current system, where candidates are looking to rally their voting bloc rather than appeal to a broader base of voters.

This uncertainty incentivizes candidates to broaden their appeal to a greater proportion of the population, effectively diffusing the power of money and privileged groups in elections and motivating candidates to be more inclusive in their campaigning efforts. The predictable, disproportionate influence of some voters over others—whether for geographical or issue-related reasons—is weakened under RWV. Both under RWV and our current electoral system, candidates will work to, obviously, attract as many votes as possible. Yet, RWV changes the way in which candidates would go about such a process.

Candidates’ confidence in the predictability of constituent behavior is significantly weakened under RWV. In close elections, some citizens might be, essentially, holding their representative accountable for actions which they do not approve. Politicians cannot rely on the diffusion of responsibility to hinder constituents’ ability to hold them responsible for broken campaign promises if any one of their constituents is able to do so. Thus, RWV directly reduces the collective action problem of holding representatives accountable, which currently enables politicians to remain predominantly free from constituency control for the majority of their time in office.

In short, the uncertainty of RWV encourages equal consideration of all voters. Candidates, campaigns, political groups, etc. will find it far more difficult to micro-target the potential electorate in any given race, forcing them to expand their campaigning efforts and engage in increased communication with more potential voters. This change would serve to further Urbinati and Warren’s norm of “democratic autonomy” in a considerable manner. By randomly weighting certain votes, RWV incentivizes candidates to expand their appeal to a broader base, campaigning in areas where, to voters who, and regarding interests that, they traditionally might ignore under our current electoral system. We can thus understand RWV as promoting an equally diffused, augmented enfranchisement, in the sense that it would encourage increased communication from candidates, specifically to a larger group of citizens, and equalize the value (from the candidate’s perspective) given to each vote, and hence the treatment of each citizen, in the electoral process.

4. Preliminary Statistical Modeling

Given the novel approach to electoral reform that this article takes—no system of randomly weighted voting has been seriously proposed before—preliminary statistical modeling is included to elucidate how RWV would function in practice.[7] This work also serves to temper concerns that such a system would lead to chaos or complete uncertainty. The data clearly shows that the proposed system (and any future variations that subscribe to similar justification) would only impact close races, defined as races won by less than 5% (Klarner).

We used Python programming software to develop models (included as appendices) that show how changing one of three variables impacts the effect of RWV.[8] The three variables under consideration are:

(1) Percentage of Supervoters (those voters who receive the random weighting).

(2) Size of Electorate.

(3) Magnitude of Supervoter Weighting.

In order to isolate the impact of each variable, we held the other two variables constant in each model:

First, given that (1) the average size of a congressional district based on the 2020 U.S. Census is 761,169 people (Epstein and Lofquist 2021) and that (2) “in recent decades, about 60% of the voting eligible population vote during presidential election years, and about 40% vote during midterm elections” (FairVote), we used a baseline electorate size of 400,000, unless otherwise noted.

Second, we used a baseline supervote weighting of 1,000x, unless otherwise noted.

Third, we used a baseline supervoter probability—the odds that any individual voter received the supervoter weighting—of 3%, unless otherwise noted.

The y-axis in each model indicates the probability (if multiplied by 100 to become a percentage) that the winner under our current voting system would still win if the election were to be conducted under the specific RWV conditions. One minus that value, and then multiplied by 100 to become a percentage, is the probability that the election, if conducted under the specified RWV conditions, would be ‘flipped’ (cause the candidate who won under our current voting system to lose).

The x-axis in each model indicates the margin of victory (as a percentage) under our current voting system. In each model, the rate of ‘flipping’ increases as the margin of victory becomes smaller.

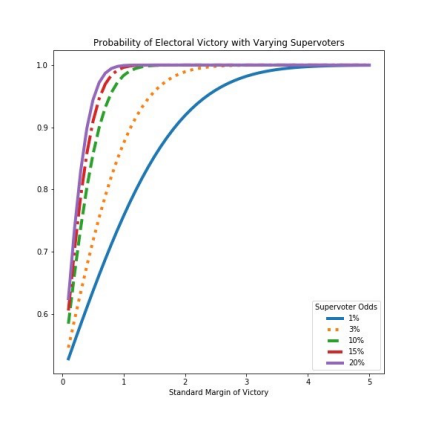

Figure A

Figure A shows five different RWV systems, altering the probability that any individual voter receives the supervoter weighting (1%, 3%, 10%, 15%, and 20%). Counterintuitively, the election becomes more random—we can observe a greater probability of election flipping over larger margins of victory—as the percentage of supervoters decreases. This effect can be attributed to the sample of supervoters displaying more randomness as it becomes smaller.

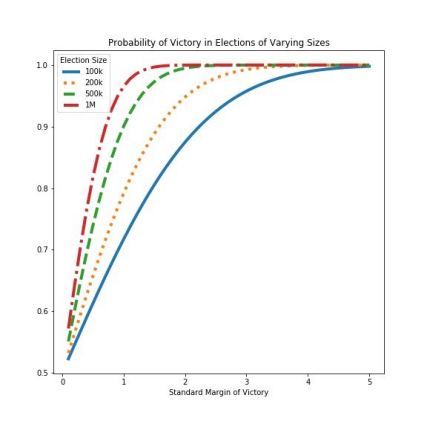

Figure B

Figure B shows four different RWV systems, altering the size of the electorate (100,000, 200,000, 500,000, and 1,000,000). With more total voters, the impact of any given random weighting is diluted. As demonstrated in the model, a 3% supervoter probability, 1,000x random weighting would have a much larger impact—a greater probability of election flipping over larger margins of victory—in an election with 100,000 total votes than an election with 1 million total votes. Thus, to preserve an equal impact upon various elections, the weighted system used would have to be a function of the size of the electorate. This scaled weighting, as determined by the size of the electorate, allows the proposed system to retain an equality of function—a consistent rate of ‘flipping’ an election outcome—across various electorate sizes.

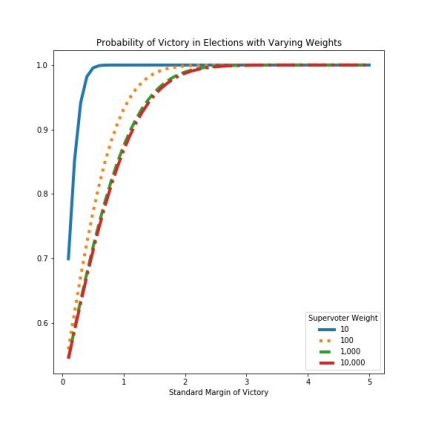

Figure C

Figure C shows four different RWV systems, altering the magnitude of the supervoter weighting (10x, 100x, 1,000x, and 10,000x the non-weighted vote). As the model shows, the greater the supervoter weighting, the greater the probability of election flipping over larger margins of victory. It is also important to note that the supervoter weighting has a diminishing effect at larger weighting values, as shown by 1,000x and 10,000x weighting curves being nearly indistinguishable from each other in the model.

The models presented in this article (for a mathematical explanation of the three models, please see the Appendix) should not be considered conclusive. None of this data is intended to specify the exact parameters of an RWV system. Rather, it is given to provide readers with a preliminary idea of how the proposed system would function in practice—under what conditions can we expect an election to result in a different outcome than under our current electoral system. Further research is necessary to find a weighting system that is:

1) Not too large as to offset the effect of the randomness or to make elections surrender completely to randomness. If the random 1,000x weighting were applied to 50% of all citizens, it would appear rational for candidates to proceed as normal in any election.[9]

2) Not too small as to have a negligible effect in all elections, and

3) Not too complicated for the general public to understand.

5. Conclusion

Randomly weighted voting does not claim to be a catch-all solution to the current problems in our democracy. Nevertheless, it offers an institutional reform that is deserving of further examination and may promote further inquiry into what other reforms might improve our electoral system. In this article, I have argued that more randomness and less certainty could make our democracy better off. However, more work is needed to fully substantiate this claim with regard to the democratic system of the United States. This article merely aims to provide a first step in a promising direction for democratic participation in elections.

Appendix

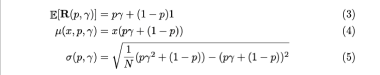

Let xi represent the vote of the ith member of the electorate. One candidate is represented by the positive votes (xi = 1) and the other by negative votes (xi = -1). The outcome of the election is the normalized sum of these vote values across all N voters:

This represents the true (non-random) margin of victory. The outcome of the randomized election is determined by randomly weighting individual votes according to a random supervoter variable R:

Where R is defined by two parameters p and g. p is the probability that a given vote will become a supervote, while g is the multiplier that supervotes receive. For example, a RWV election in which 3% of the votes are counted 1,000 times has R(.03, 1000). Using the expected value of R(p, g) we derive the mean and standard deviation of random election outcomes x̂ :

The probability of the negative candidate winning the election is the cumulative distribution function for the normal distribution N (µ (x, p, g), s( p, g)2) evaluated at a tied election (x̂ = 0).

The probability of the positive candidate winning the election is the complement probability 1-W (x, p, g).

References

Achen, C. (1975). Mass Political Attitudes and the Survey Response. American Political Science Review, 69, 1218-1231.

Argarwal, P. (2018). Consumer Sovereignty. Intelligent Economist. https://www.intelligenteconomist.com/consumer-sovereignty/ (Accessed 4 April 2021).

Balz, D. (2014). Why So Many Americans Hate Politics. The Washington Post. 23 August 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/why-so-many-americans-hate-politics/2014/08/23/e56dbaf0-18d5-11e4-9e3b-7f2f110c6265_story.html (Accessed 5 May 2021).

Bartels, L. (2003). Democracy With Attitudes. In M. McKuen and G. Rabinowitz (Eds.) Electoral Democracy (48-82). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Brennan, G. and Sayre-McCord, G. (2016). Voting and Causal Responsibility. Oxford Studies in Political Philosophy, 1, 499-513.

Dahl, R. (1970). After the Revolution? Authority in a Good Society. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Darmofal, D. (2010). Reexamining the Calculus of Voting. Political Psychology, 31, 149-174.

Disch, L. (2011). Towards a Mobilization Conception of Democratic Representation. American Political Science Review, 105(1), 100-114.

Dittmann, I., Kübler, D., Maug, E., Mechtenberg, L. (2014). Why Votes Have Value: Instrumental Voting With Overconfidence And Overestimation of Others’ Errors. Games and Economic Behavior, 84(1), 17-38.

Epstein, B. and Lofquist, D. (2021). U.S. Census Bureau Today Delivers State Population Total For Congressional Apportionment. United States Census Bureau. 26 April 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/04/2020-census-data-release.html (Accessed 27 April 2021).

FairVote, Voter Turnout in the United States. https://www.fairvote.org/voter_turnout#voter_turnout_101 (Accessed 10 February 2021).

Glynn, J. (2017). American Voters: The Dumb, the Disinformed, and Disillusioned. Arts and Sciences Journal, 8, 1-4.

Goldman, A. (1999). Why Citizens Should Vote: A Causal Responsibility Approach. Social Philosophy and Policy, 16, 201-217.

Guerrero, A. (2014). Against Elections: The Lottocratic Alternative. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 42(2), 135-178.

Jackson, K. (2020). What Makes an Administrative Agency “Democratic?”. The Law and Political Economy Project. 11 November 2020. https://lpeproject.org/blog/what-makes-an-administrative-agency-democratic/ (Accessed 10 April 2021).

Key Jr., V.O. (1966). The Responsible Electorate: Rationality in Presidential Voting 1936-1960. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kinnard, M. (2020). Despite Massive Democratic Fundraise, Graham Easily Wins SC. AP News, 4 November 2020. https://apnews.com/article/senate-elections-jaime-harrison-campaigns-lindsey-graham-south carolina8e132424f3f468c8aaf9806ba2c2c965 (Accessed 5 February 2021).

Klarner, C. (2015). Competitiveness in State Legislative Elections: 1972-2014. Ballotpedia. 6 May 2015. https://ballotpedia.org/Competitiveness_in_State_Legislative_Elections:_1972-2014 (Accessed 2 May 2020).

Kleinfeld, R., et al. (2018). Renewing U.S. Political Representation: Lessons from Europe and U.S. History. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 12 March 2018. https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/03/12/renewing-u.s.-political-representation-lessons-from-europe-and u.shistory-pub-75758 (Accessed 5 March 2020).

Koerth, M. (2018). How Money Affects Elections. FiveThirtyEight, 10 September 2018. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/money-and-elections-a-complicated-love-story/ (Accessed 18 February 2021).

Kreig, G. (2012). What is a Super PAC? A Short History. ABC News. 8 August 2012. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/OTUS/super-pac-short-history/story?id=16960267 (Accessed 14 February 2021).

Kuenzler, A. (2017). Restoring Consumer Sovereignty: How Markets Manipulate Us and What the Law Can Do About It. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lau, T. (2019). Citizens United Explained. Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law. 12 December 2019. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/citizens-united-explained (Accessed 10 February 2021).

Lessig, L. (2019). They Don’t Represent Us: Reclaiming Our Democracy. New York: HaperCollins Publishers.

Madison, J. or Hamilton, A. (1788). The Federalist Papers: No. 57. The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. 19 February 1788. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed57.asp (Accessed 16 January 2021).

Mansbridge, J. (2017). Recursive Representation in the Representative System. Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series.

Mansbridge, J. (2003). Rethinking Representation. American Political Science Review, 97(4), 515-528.

Martin, M. (2008). Nonconnected Committees. https://www.fec.gov/resources/cms-content/documents/nongui.pdf. Federal Election Commission Campaign Guide (Accessed 10 September 2020).

McCann, A. (2020). States with the Most and Least Powerful Voters. WalletHub. 26 October 2020. https://wallethub.com/edu/how-much-is-your-vote-worth/7932 (Accessed 15 April 2021).

Miklosi, Z. (2012). Against the Principle of All-Affected Interests.” Social Theory and Practice, 38(3), 483-503.

MLive Media Group (2020). Political Groups Spend Millions on Ads to Turn Michigan Republicans Against Trump Over Coronavirus Response. 9 July 2020. https://www.mlive.com/public-interest/2020/07/political-groups-spend-millions-on-ads-to-turn-michigan-republicans-against-trump-over-coronavirus-response.html (Accessed 9 July 2020).

Mueller, D. (2003) Public Choice III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nagel, J. (1975). The Descriptive Analysis of Power. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Nott, L. (2020). Political Advertising on Social Media Platforms. American Bar Association: Human Rights Magazine, 46(3). 26 June 2020. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/voting-in 2020/politicaladvertising-on-social-media-platforms/ (Accessed 13 January 2021).

Open Secrets. https://www.opensecrets.org/online-ads.

Page, B. and Shapiro, R. (1992). The Rational Public: Fifty Years of Trends in Americans’ Policy Preferences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pitkin, H. (1967). The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Prokop, A. (2014). 40 Charts that Explain Money in Politics. Vox. 30 July 2014. https://www.vox.com/2014/7/30/5949581/money-in-politics-charts-explain (Accessed 3 May 2021).

Reelection Rates Over the Years. The Center for Responsive Politics: OpenSecrets. https://www.opensecrets.org/elections-overview/reelection-rates (Accessed 16 February 2021).

Robbins, S. (2018). Money in Elections Doesn’t Mean What You Think it Does. University of Florida News. 29 October 2018. https://news.ufl.edu/articles/2018/10/money-in-elections-doesnt-mean-what-you-think-it-does.html (Accessed 4 May 2020).

Samples, J. (2012). SpeechNow, the Decision that Made a Difference. Cato Institute. 20 January 2012. https://www.cato.org/blog/speechnow-decision-made-difference (Accessed 18 November 2021).

Spenkuch, J. (2018). Expressive vs. Strategic Voters: An Empirical Assessment.” Journal of Public Economics, 165, 73-81.

The New York Times (2021). 24th Congressional District. National Election Pool/Edison Research, in The New York Times. 22 February 2021, updated. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/11/03/us/elections/results texashouse-district-24.html (Accessed 8 March 2020).

Tuck, R. (2008). Free Riding. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Urbinati, N. and Warren, M. (2008). The Concept of Representation in Contemporary Democratic Theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 387-412.

Van Reybrouk, D. (2016). Against Elections: The Vase for Democracy. London: Random House UK.

Victor, J. (2018). What Good are Elections, Anyway? Vox. 30 October 2018. https://www.vox.com/mischiefs offaction/2018/10/30/18032808/what-good-are-elections (Accessed 24 March 2020).

Wong, J. (2018). ‘It Might Work Too Well’: The Dark Art of Political Advertising Online. The Guardian. 19 March 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/mar/19/facebook-political-ads-social-media-history onlinedemocracy (Accessed 26 January 2021).

- This term was suggested by Professor Colin Bird (University of Virginia). ↵

- As Disch (2011, 101) notes, “empirical researchers use the term ‘political environment’ to designate the ‘totality of politically relevant information to which citizens are exposed’ by various mediating institutions ... It functions for them as a way to speak of what normative theorists would call the 'public sphere,' without crediting that environment with the virtues of equality, openness, reasonableness, etc.” ↵

- According to Prokop (2014), in 2010, 0.26% of the population contributed 68% of the political donations to congressional campaigns, exerting disproportionate influence over these races. ↵

- There are also institutional de facto weightings that exist within the United States. For example, as McCann (2020) clarifies, “it’s extremely likely that a Republican senator from Kentucky and a Democratic senator from Delaware will both be re-elected. But voters’ choices for senators in swing states hold much more power because they determine which political party controls the Senate.” ↵

- The standard public choice account of voting focuses on the instrumental value of a vote. Mueller (2003, 305) writes, “voting is a purely instrumental act in the theory of rational voting. One votes to bring about the victory of one’s preferred candidate.” He continues, “thus, in deciding whether to vote, a rational voter must calculate the probability that her vote will make or break a tie…” ↵

- A thorough discussion of what ‘more educated’ means is beyond the scope of this article. However, we can understand “more educated voters” as having additional knowledge of the policy positions and relevant political information about the candidates in a given race and engaging in more educative processes (such as viewing debates, reading articles about the candidates’ platforms, and directly engaging with campaigns) before voting. ↵

- Although unused in political science, ensembled predictions and random weighting are commonly used in computer science to improve the accuracy of decision-making systems. ↵

- All modeling for this article was completed by the author and Jefferson Grigsby (a mathematics and computer science major). ↵

- This implication evolved from a discussion with Professor Alex Guerrero (Rutgers University). ↵