3. Analyze Organizational Performance

After engaging with this chapter, you will understand and be able to apply the following concepts.

- Mission, purpose, vision, and values

- Performance measures and benchmark measures

- A range of organizational performance measures

- Balanced scorecard

- Competitive advantage

You will be equipped to analyze a firm’s

- Mission, purpose, vision, and values

- Financial position

- Market position

- Other relevant quantitative data

- Balanced scorecard

3.1 Introduction

In Part I, you were introduced to strategic management and case analysis. This chapter continues to follow the AFI framework, expanding on the case analysis process and teaching you how to analyze a firm’s organizational performance.

You now know that strategic management’s foundations rest in three questions:

- Where are we?

- Where are we going?

- How are we going to get there?

You also know that these three questions align with the three major stages of strategic management according to the AFI framework: strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation. Strategic analysis addresses the broad question “Where are we?” Strategy formulation begins to answer “Where are we going?” Strategy implementation addresses the final question, “How are we going to get there?”

In this chapter, you learn key organizational performance measures and how to analyze them. You learn what mission, purpose, vision, and values mean to a company, why they are important, and how to analyze them. This chapter also discusses the difference between performance measures and benchmark measures and the importance of considering a range of measures to ensure a thorough and robust analysis. Therefore, you learn multiple approaches to analyze a company’s organizational performance, focusing on and analyzing a firm’s financial position, market position, and other relevant quantitative measures. You also learn a model for measuring organizational performance, the balanced scorecard, and how to analyze it to provide a more comprehensive view of a firm’s organizational performance. Finally, you learn what a competitive advantage is and why it is central to strategic management.

This is step one in case analysis.

1. Analyze a firm’s organizational performance.

- Use the organizational performance analysis instrument to analyze a firm’s organizational performance.

- Analyze, interpret, and evaluate the firm’s mission, purpose, vision, values, and goals.

- Evaluate line of sight and congruence among the firm’s mission, purpose, vision, and values.

- Analyze, interpret, and evaluate the firm’s financial position.

- Analyze, interpret, and evaluate the firm’s market position.

- Analyze, interpret, and evaluate additional relevant quantitative measures of organizational performance.

- Analyze, interpret, and evaluate a firm’s balanced scorecard.

- Evaluate line of sight and congruence among the measures in the balanced scorecard.

- Analyze, interpret, and evaluate the firm’s mission, purpose, vision, values, and goals.

- Common-size data and present trends to ensure the analysis is meaningful.

Throughout the text, we introduce analysis instruments to support your analysis. Use the organizational performance analysis instrument to analyze a firm’s organizational performance.

Organizational performance analysis instrument

Download an editable version or view this resource in Appendix 1.

3.2 Analyze Mission, Purpose, Vision, and Values

Collectively, a firm’s mission, purpose, vision, and values set clear organizational direction that guides all firm decisions and strategies. Organizational leaders define these factors for the firm and then express them in statements for their stakeholders. It is important that there is a clear line of sight and congruence among these essential organizational elements. If there is no congruence or weak congruence between any or all of these, the organization will not have clear direction, and this can lead to poor decisions, weak strategies, and overall poor organizational performance. Of course, strong guiding statements do not guarantee superior firm performance. A company may have excellent mission, purpose, vision, and values and still make misguided strategic leadership decisions. However, this does not make it any less important for those four elements to be strong, clear, and congruent.

It is not enough for strategic leaders to just ensure that an organization’s mission, purpose, vision, and values are aligned; they also need to align their leadership approach with these factors. Strategic leadership that is aligned to a company’s mission, purpose, vision, and values has the potential to inspire employees, who feel the firm’s leadership is authentic and that they are empowered to contribute meaningfully to the firm’s performance. This powerful authenticity has the potential to lead an organization toward excellent performance.

Collectively, an organization’s mission, purpose, vision, and values serve as the foundation for all strategic decisions. They inform every aspect of a business, both external and internal. For example, among other things, they inform marketing approaches, asset management approaches, and decisions to cooperate with other organizations. They also influence organizational structure, human resource policies, and organizational culture.

The primary emphasis for a firm defining and expressing these guiding factors is to capture the organization’s distinctiveness. Missions, purposes, visions, and values that are both distinct and authentic have the potential to drive excellent performance.

The first step in analyzing a firm’s organizational performance is to assess its mission, purpose, vision, and values. In analyzing them, the first important question to ask is whether they are effective. Then consider whether there is a clear line of sight among them and whether they are congruent. If the answer to either is no, recommend that the company revisit these and bring them into alignment.

Not only does there need to be a clear line of sight and congruence among the mission, purpose, vision, and values, strategies must align with them as well. If strategies do not align, they either need to be adjusted or dropped, or in some cases, the mission, purpose, vision, and values should be revised to stay relevant.

It is important to understand how mission, purpose, vision, and values relate and how they are distinct. It is most important to understand the concepts behind each and what each aims to accomplish because not all organizations consider and communicate through all four of the guiding statements. Some companies combine the ideas behind two of the factors, and sometimes companies use different names for the same ideas. When analyzing a company, it is more important to assess whether each broad concept is dealt with and communicated than whether a company uses each of these exact terms.

We now review each of these in turn.

Analyze Mission

Missions and mission statements are important for all firms. They are essential for industry leaders who seek to maintain their positions and drive continued success. When working to revitalize an organization, leaders often focus on reaffirming its commitment to a clear mission.

A mission statement explains why an organization exists. A well-crafted mission statement captures the essence of the organization and answers the questions “Why do we exist?” and “What is our purpose?” For example, a nonprofit might have a mission “to provide access to clean water in underserved communities,” which clearly expresses why it exists. The mission defines the organization’s role within society. Just as important as the firm’s purpose is its identity, addressed in questions like “What defines us?” and “Who are we?” A mission is rooted in the firm’s past foundation and current identity. Since a mission statement captures the essential elements of the company’s identity from its founding to its reason to exist in the present, mission statements are often written in the present tense.

In practice, a mission statement also serves to inform key stakeholders why they should invest their trust, resources, and support in the organization. For an organization to succeed, it must gain the support of key stakeholders such as employees, owners, suppliers, partners, and customers.

For example, Google’s mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” (Google.com). Early on, Google pursued this mission by developing a widely popular search engine. Today, the company continues to align with its mission through various strategic efforts, such as providing the Google Chrome browser, offering free email services through Gmail, and making books available for online browsing.

Deloitte offers professional services such as consulting, auditing, and advising to assist businesses in resolving difficult problems and accomplishing their objectives. In this regard, it is clear Deloitte has concentrated on its mission statement: “To make an impact that matters by delivering measurable, sustainable results to clients and communities” (Deloitte).

Another example is Peloton. Peloton makes fitness accessible by providing the most effective tools, software, content, and guidance. With its linked stationary bikes and streaming fitness classes, they engage in interactive at-home workouts and fitness technology. In efforts to strengthen its brand and direction, Peloton has focused on its mission statement: “Peloton uses technology and design to connect the world through fitness, empowering people to be the best version of themselves anywhere, anytime” (Peloton.com).

Mission statements are often brief and easy to remember. In the past, they tended to be much longer, sometimes spanning several paragraphs, which made it difficult for employees and other stakeholders to recall or recite them. Over time, companies have simplified their mission statements, making them shorter and more memorable. When employees know and embrace their organization’s mission, it boosts their engagement and overall satisfaction. For instance, Nike’s simple mission “to bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world” (Nike.com) is easy for employees to internalize and work toward.

When you analyze a firm’s mission statement, consider to what degree it addresses the criteria of a strong mission statement. It is not necessary that the mission statement meets every one of these criteria. After all, strong mission statements are short. Use this list as a guide to make your own assessment:

- Does the mission statement explain why the organization exists?

- Does the mission statement define the organization’s role within society?

- Is the mission statement rooted in the firm’s past foundation and current identity?

- Does the mission statement capture the essential elements of the company’s identity?

- Is the mission statement written in the present tense?

- Does the mission statement inform key stakeholders, such as employees, owners, suppliers, partners, and customers, why they should invest their trust, resources, and support in the organization?

The mission of an organization serves as a foundation for its purpose, vision, and values. We now turn our attention to an organization’s purpose.

Analyze Purpose

In recent years, many organizations have increasingly embraced the concept of using a purpose statement to articulate their reason for existence beyond just profit-making, which differentiates them from mission statements.

Purpose statements are designed to inspire and unite stakeholders, ranging from employees to customers, around a central purpose. Unlike mission statements, purpose statements often focus on the broader impact an organization seeks to have on society or its industry. By highlighting the company’s contributions beyond its products or services, purpose statements can help organizations foster trust, loyalty, and a sense of shared responsibility. Purpose statements often reflect a company’s stance toward sustainability. Sometimes a company will publish a separate sustainability statement. Sustainability is reviewed in detail in Chapter 10.

A well-crafted purpose statement also serves as a strategic guide, helping organizations navigate complex decisions by providing a clear framework for evaluating opportunities and challenges. When a company’s actions and initiatives are aligned with its stated purpose, it ensures consistency in decision-making. This alignment fosters long-term success, as organizations are more likely to prioritize initiatives that resonate with their purpose and contribute to their broader goals. In turn, this can enhance the firm’s reputation and attract not only customers but also partners and talent who share a similar vision for the future. With this focus on the current actions the company is taking, purpose statements are usually written in the present tense.

For example, PwC’s purpose is to “build trust in society and solve important problems” (PwC.com). This statement reflects the company’s commitment to addressing critical challenges facing global communities, positioning itself as a trusted partner in fostering societal progress. By aligning their operations and goals with a clearly defined purpose, organizations like PwC are better able to engage their workforce, attract like-minded clients, and create lasting, meaningful impact.

Not every company defines a purpose separate from its mission. Some companies address their purpose beyond profit-making in their mission statements. When analyzing a firm’s broad guidance as it is communicated through its missions, purpose, vision, and values, it is most important to assess whether the company defines and articulates its purpose in addition to profit-making, whether this is expressed separately in a purpose statement, presented as part of the mission, or even included in another statement.

When you analyze a firm’s purpose statement, consider to what degree it addresses the criteria of a strong purpose statement. As with your analysis of the firm’s mission statement, it is not necessary that the purpose statement meets every one of these criteria. Use this list as a guide to make your own assessment:

- Does the purpose statement articulate a firm’s reason for existence beyond just profit-making?

- Does the purpose statement focus on the broader impact an organization seeks to have on society or its industry?

- Is the purpose statement written in the present tense?

- Does the purpose statement inspire and unite stakeholders?

- Does the purpose statement foster trust, loyalty, and a sense of shared responsibility?

- If a company has not articulated a separate purpose statement, has it addressed the criteria above somewhere else?

With mission and purpose defined, company leaders define their vision and communicate this through a vision statement.

Analyze Vision

An organizational vision statement is a forward-looking or aspirational statement that captures what a company wants to achieve in the long run. It’s meant to inspire and guide the organization, offering a clear sense of direction. A good vision paints a picture of a hopeful future, helping to align everyone around the same vision. Vision statements are usually concise, easy to understand, and motivate people by showing them what they’re working toward. Unlike mission and purpose statements, they are usually written in the future tense.

A compelling vision statement can be a powerful tool that leaders can use to energize and align the organization toward where it wants to be. A clear vision defines what the company aspires to become and helps to shape its strategies. For instance, LinkedIn’s vision is to “[c]reate economic opportunity for every member of the global workforce” (LinkedIn.com). This succinct yet ambitious vision highlights the company’s aspirations to reach every member of the global workforce and assist them by creating economic opportunities. Consequently, one might expect LinkedIn to feverishly pursue expansion of its offerings around the globe.

One might question the importance of vision statements. How much effect could they have, after all? More than fifty studies have demonstrated a relationship between vision statements and achieving desired outcomes (Kirkpatrick & Locke, 2012). Not all vision statements are good, and not all lead to success. Effective vision statements are generally clear, future focused, abstract and challenging, idealistic, concise, unique, and define success (Hauser, House, Kirkpatrick, & Locke, 2017).

While a well-defined vision can inspire employees, customers, and other stakeholders, strong and effective visions are relatively uncommon. Vision is the starting point of strategy. Strategy defines the roadmap of how an organization will move from where it is today to where it wants be according to its vision.

An organization can’t thrive if its mission and vision are not aligned. When a company’s mission and vision point in different directions, confusion and inefficiency affect the strategy. For example, early in the development of some companies in the tech industry, their missions were focused on providing accessible and innovative products for consumers. However, as they grew, some shifted their visions toward dominating markets or expanding into unrelated areas, creating a conflict between what they originally stood for and what they aspired to become.

A more recent example comes from higher education. Many universities started with missions centered around providing quality education to students. As the need for research and innovation grew, the visions of some universities shifted to prioritize global research prestige. This created confusion among faculty: should they focus on teaching, as the mission suggests, or on research, as the vision demands? Even today, some institutions struggle to reconcile this tension, as the different emphases create competing priorities for faculty and staff.

Ultimately, organizations are most successful when mission and vision are aligned. A tech company that aims for both customer-centric innovation and market leadership, for example, will be more effective if its mission and vision work together to guide employees in the same direction despite having two potentially conflicting goals.

When you analyze a firm’s vision statement, consider to what degree it addresses the criteria of a strong vision statement. As with your analysis of the firm’s mission and purpose statements, it is not necessary that the purpose statement meets every one of these criteria. Use this list as a guide to make your own assessment:

- Is the vision statement a forward-looking or aspirational statement that captures what a company wants to achieve in the long run?

- Does the vision statement inspire and offer a clear sense of direction?

- Does the vision statement paint a picture of a hopeful future?

- Is the vision statement concise and easy to understand, with the potential to motivate people by showing them what they’re working toward?

- Is the vision statement written in the future tense?

- Is the vision statement aligned with the mission statement?

Once a company has confirmed their current position with strong mission and purpose statements and articulated their aspirations for the future through their vision, they can then consider their values. A company’s vision serves as the foundation for its values and goals, which in turn guide the organization toward achieving that vision.

Analyze Values

In addition to crafting mission, purpose, and vision statements, companies also create corporate value statements that define the core principles they stand by and expect their employees to uphold. These values are often showcased on company websites to communicate what the organization believes in and strives for.

Value statements are important because they not only guide internal culture but also influence how the company is perceived by stakeholders. Employees are expected to align with these values, and those who don’t may find their tenure short-lived. Customers often choose companies whose values resonate with their own and firms that clearly communicate their principles. When Nike faced backlash over labor practices, the company revised its value system to emphasize fair labor conditions, showing how values impact both internal policies and public image. Likewise, Ben & Jerry’s commitment to social justice can build strong brand loyalty. Values statements are usually written in the present tense.

Values are also tightly intertwined with strategic management. When formulating strategies and goals, companies must ensure alignment with their value statements. For example, if a strategy conflicts with a core value like sustainability, it must be reconsidered or adjusted. Companies like Tesla, which prioritizes environmental sustainability (Tesla.com), would likely reject strategies that compromise that value, even if profitable in the short term. Adhering to corporate values ensures that companies maintain their integrity while progressing toward their long-term goals.

| Company | Values statement |

|---|---|

| KPMG | Integrity: We do what is right. Excellence: We never stop learning and improving. Courage: We think and act boldly. Together: We respect each other and draw strength from our differences. For Better: We do what matters. |

| Wells Fargo | We want to satisfy our customers’ financial needs and help them succeed financially. |

| RSM | Respect and uncompromising integrity Succeeding together Excellence Impactful innovation Acting responsibly |

Figure 3.2: Values and values statements

Companies like Microsoft emphasize values such as innovation (Microsoft.com), while others, like Patagonia, are known for promoting sustainability and environmental responsibility (Patagonia.com).

Some companies articulate both purpose and values statements, and some only define one. Purpose and values are similar and distinct. Purpose statements articulate the firm’s reason for existence beyond just profit-making, instead focusing on the broader impact an organization seeks to have on society or its industry, such as AT&T’s purpose statement, “Connecting people to greater possibility—with expertise, simplicity, and inspiration.” Value statements define the core principles that companies stand by and expect their employees to uphold, such as RSM’s value of impactful innovation. While purpose statements may explain the goals of the firm, the value statement explains why those goals are important. When analyzing a company, it is more important to assess whether the firm addresses the broader impact it seeks to have on society or its industry (purpose) and defines the core principles it stands by (values) than it is to focus on where exactly this is communicated.

When you analyze a firm’s values statement, consider to what degree it addresses the criteria of a strong values statement. As with your analysis of the firm’s mission, purpose, and vision statements, it is not necessary that the values statements meet every one of these criteria. Use this list as a guide to make your own assessment:

- Does the values statement define the core principles the firm stands by and expects its employees to uphold?

- Does the values statement have the potential to guide organizational culture and also influence how the company is perceived by stakeholders?

- Does the company articulate a separate sustainability statement?

- Is the purpose statement written in the present tense?

A company’s values reflect their current commitment to a set of guiding principles. Values focus on where the company is headed by setting the parameters for the firm’s goals. The company defines and executes its goals by remaining true to its values.

Complete the section titled “Mission Purpose Vision Values” in the organizational performance analysis instrument.

Application

- The same principles that guide successful organizations in defining their mission, purpose, vision, values, and goals can be just as useful for individuals. Thinking strategically about your personal aspirations and how you plan to achieve them can offer new insights and approaches. Consider applying these concepts to your own life to help clarify your goals, stay focused on your purpose, and map out the steps needed to move forward effectively.

Organizational leaders define the firm’s mission, purpose, vision, and values then express them in statements for their stakeholders. These are usually published on company websites and easy to find. A mission statement explains why an organization exists. A firm’s purpose statement articulates the reason for the company’s existence beyond just profit-making. A vision statement is a forward-looking or aspirational statement that captures what a company or organization wants to achieve in the long run. Value statements define the core principles that companies stand by and expect their employees to uphold. It is important that there is a clear line of sight and congruence among these essential organizational elements. When analyzing an organization’s mission, purpose, vision, and values, the first important question to ask is whether they are effective. Then ask whether there is a clear line of sight among them and whether they are congruent. If not, recommend that the company revisit these and bring them into alignment.

Bibliography

Bart, C. K. (1997). Industrial firms and the power of mission. Industrial Marketing Management, 26(4), 371–383.

Bart, C. K. (2001). Measuring the mission effect in human intellectual capital. Journal of Intellectual Captial, 2(3), 320–330.

Bart, C. K., & Baetz, M. C. (1998). The relationship between mission statements and firm performance: An exploratory Study. Journal of Management Studies, 3(6), 823–853.

Carton, A. M., Murphy, C., & Clark, J. R. (2014). A (blurry) vision of the future: How leader rhetoric about ultimate goals influences performance. Academy of Management Journal, 57(6), 1544–1570. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0101

Deloitte. (n.d.). Our shared beliefs. Deloitte. https://www.deloitte.com/lu/en/about/story/purpose-values/culture-beliefs.html

Dili, A. (n.d.). Vision, values, and strategy. Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/az/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/vision-values-strategy.html

Hauser, M., House, R. J., Kirkpatrick, S. A., & Locke, E. A. (2017). Understanding the role of vision, mission, and values in the HPT model. Performance Improvement, 56(3), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405164047.ch18

Kirkpatrick, S. A., & Locke, E. A. (2012). Lead through vision and values. In Handbook of principles of organizational behavior: Indispensable knowledge for evidence‐based management, 367–387. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119206422.ch20

Deloitte. (n.d.). Making an impact that matters, together. Deloitte. https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/about/story/purpose-values.html

Quigley, J. V. (1994). Vision: How leaders develop it, share it, and sustain it. Business Horizons, 37(5), 37–41.

Rogers, B. (2013). ‘Culture of purpose’ is key to success according to new research from Deloitte. Forbes.

3.3 Performance Measures and Performance Benchmarks

Once you have analyzed a firm’s mission, purpose, vision, and values, next consider the firm’s performance in others critical areas using comparative measures—specifically performance measures and performance benchmarks.

Performance measures are metrics used to track an organization’s progress, such as profits, stock prices, or sales figures. These metrics provide insights but only offer a partial view of overall performance.

Performance benchmarks, on the other hand, provide context by comparing an organization’s metrics to its previous results or to those of competitors. For example, a company showing a profit margin of 20 percent in 2024, might seem like a strong performance. However, if that same company had a profit margin of 35 percent in the previous year, and the industry average for 2024 was 40 percent, this new result would indicate a decline.

Application

- Consider the ways your performance is measured. How is your academic success measured? For example, your grades and GPA are performance measures. Your class standing is a measure of your academic standing as measured against other students in your class.

- Think of other ways your performance is measured. Do you work out or play sports? Do you play a musical instrument or sing? Do you have a job? How is your performance measured in non-academic settings? What is the value of using both performance measures and performance benchmarks in evaluating your work?

Performance measures are metrics used to track an organization’s progress, such as profits, stock prices, or sales figures. Performance benchmarks are standards or reference points used to evaluate an organization’s metrics by comparing them to historical data, industry standards, or the performance of competitors. You can analyze a firm’s performance using both performance measures and performance benchmarks.

3.4 Analyze a Firm’s Financial and Market Positions and Other Relevant Quantitative Data

Once you have analyzed a firm’s mission, purpose, vision, and values, the next step is to analyze a firm’s financial and market positions and other relevant quantitative data.

We begin by analyzing a firm’s financial position.

Analyze a Firm’s Financial Position

An essential measure of organizational performance is a firm’s financial landscape, which is visualized through analysis of financial data from the industry, competitors, and the firm.

Conducting a financial analysis of a firm is not always straightforward. The method and calculations are simple enough, and the key measures are reviewed below. The complexity lies in finding useful data, deciding which data is meaningful in this context, and presenting the data in an easily digestible format.

The challenge of grasping the complex nature of organizational financial performance stems from the conflicting views that can arise from using different benchmarks and metrics. For instance, the Fortune 500 ranks the largest U.S. companies based on sales, but these companies are not necessarily the best performers in terms of stock price growth. Due to their size, companies like Apple (as of 2024) would find it nearly impossible to double their revenue, whereas a smaller pharmaceutical company launching a new drug could see exponential revenue growth. In the late 1990s, many internet-based businesses experienced rapid sales and stock price growth despite posting losses. Investors who focused solely on sales growth suffered significant losses when the market shifted its attention to profits and stock prices plummeted.

Despite the problems with these metrics, almost all publicly traded companies discuss measures such as revenue and net income (Certo, Jeon, Raney, & Lee, 2024). This demonstrates the need for executives to carefully select a balanced yet manageable set of performance indicators to focus on, ensuring they capture a comprehensive picture without being swamped by excessive data.

Financial measures are key tools for evaluating an organization’s profitability and overall effectiveness. These include essential metrics like return on assets (ROA), which measures how effectively a company turns its assets into profit. A high ROA suggests efficient asset use, while a low or negative ROA signals inefficiency. Additional financial measures include return on equity (ROE) and return on investment (ROI), which offer insight into how efficiently a company is using its resources.

Other popular financial indicators include earnings per share (EPS), net profits, and stock price, which together help answer the crucial question “How do we appear in the eyes of our shareholders?”

These financial metrics are typically featured in annual (10-K) and quarterly (10-Q) reports, providing stakeholders with a transparent snapshot of the organization’s fiscal health. For these numbers to be meaningful, they need to be paired with relevant comparisons, such as the company’s performance over time or industry benchmarks. For instance, in Tesla’s 2022 annual report, the company highlighted its financial performance over the past five years, focusing on revenue growth, operating margins, and cash flow, which allowed shareholders to gauge the company’s progress and future potential.

This method of financial analysis revolves around ratio analysis, which enables comparisons across companies or time periods, regardless of size or scale. Ratios like profit margins, debt-to-equity ratios, and asset turnover provide an even playing field for comparing firms across different operational scales.

| Types of measures | Ratio | Formula | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquidity measures | Current ratio (CR) | Current assets / Current liabilities | Indicates ability to pay short-term obligations | Target uses CR to assess its ability to cover short-term obligations with its available assets. |

| Leverages measures | Debt ratio (DR) | Total liabilities / Total assets | Shows the proportion of assets financed through debt | Apple evaluates its DB to understand how much its assets are financed through debt. |

| Profitability ratios | Gross margin (GM) | Gross profit / Total revenue | Percentage of revenue remaining after direct costs | Starbucks uses GM to see the percentage of revenue left after covering direct costs like coffee beans and milk. |

| Net profit margin (NPM) | Net profit / Net revenue | Shows profit earned per dollar of revenue | Netflix examines its NPM to determine profit per dollar after all expenses. | |

| Return on equity (ROE) | Net profit / Shareholder equity | Measures profitability relative to equity financing | Goldman Sachs reviews ROE to gauge how effectively it uses shareholders’ equity to generate profits. | |

| Return on assets (ROA) | Net profit / Total assets | Assesses efficiency in using assets to generate profit | Tesla checks ROA to measure how efficiently it uses assets like factories to produce profits. | |

| Return on investments (ROI) | (Net profit / Investment cost) x 100 | Assesses profitability relative to the cost of investment | Apple measures ROI for evaluating the success of new products. | |

| Efficiency ratios | Inventory turnover (IT) | Cost of goods sold (COGS) / Average inventory | Indicates how efficiently inventory is managed | Walmart tracks IT to understand how quickly it sells and restocks products. |

| Accounts receivable turnover (ART) | Net credit sales / Average accounts receivable | Assesses efficiency of accounts receivable management | Microsoft tracks ART to evaluate how quickly it collects payments from customers. | |

| Market value | Market capitalization (MC) | Shares outstanding × Share price | Reflects the overall market value of the company | Amazon uses MC to understand its overall market value based on stock prices and shares. |

| Earnings per share (EPS) | Net income / Number of outstanding shares | Shows the profitability attributed to each share of stock | Amazon tracks EPS to evaluate its profitability per shareholder. | |

| Net profit | Total revenue – Total expenses | Reflects the overall profit a company generates | Netflix analyzes net profits to evaluate a company’s financial health. | |

| Stock price | The market valuation of one share of the company | Indicates how investors perceive the company’s future performance | Microsoft monitors its stock price to track shareholder sentiment. |

Figure 3.4: Finance ratios (bolded items indicate glossary terms)

Complete the section titled “Financial Position” in the organizational performance analysis instrument.

Analyze a Firm’s Market Position

Analyzing a firm’s market position assesses how a firm compares to its competitors within the market. Two common measures for evaluating a company’s market position are market share and price–earnings (PE) ratio.

Market Share

Formula: Firm’s Total Product Revenue / Total Revenue in the Industry

Market share reflects the percentage of the market controlled by a company. For example, if Netflix generates 35 percent of the total revenue in the global streaming industry, then its market share in that sector is 35 percent.

Price–Earnings (PE) Ratio

Formula: Stock Price / Earnings per Share (EPS)

The PE ratio shows how much investors are willing to pay for $1 in earnings. If a company’s stock is priced at $50 per share and generates $5 in annual earnings per share, the PE ratio is 10. A lower PE ratio suggests better value, while a higher PE ratio might indicate strong market confidence in the company’s future growth prospects. For instance, a company like Tesla often has a high PE ratio due to market optimism about future earnings growth.

Complete the section titled “Market Position” in the organizational performance analysis instrument.

Analyze a Firm’s Other Relevant Quantitative Data

Other data sets and trends can offer valuable insights. Trend analysis, for example, can reveal year-over-year changes in production volume or help forecast economic conditions. Insight can come from company-related data like customer satisfaction rates derived from surveys, employee satisfaction, strength of the brand, and innovation strengths (measured in new patents and new products launched). Demographic data can also be useful, such as forecasts for population growth. Analyzing the age and gender forecasts in a population can give important insights into potential new customers. Additionally, industry-specific data can offer useful benchmarks, enabling the analysis of a company’s performance relative to average sector growth or innovation rates. By focusing on these different areas—financial, market-based, and general quantitative measures—organizations ensure they have a well-rounded view of their performance and are positioned for long-term success.

Complete the section titled “Other Quantitative Measures” in the organizational performance analysis instrument.

Video 3.1: What Is Organizational Performance? [01:56]

The video for this lesson explains how some organizations assess their organizational performance.

Analyze a firm’s financial and market positions and other relevant quantitative data. Analyze financial data from the industry, competitors, and the firm. Competence with the finance measures in figure 3.4 is essential to conducting a financial analysis of a firm when you conduct a case analyses. Analyzing a firm’s market position assesses how a firm compares to its competitors within the market. Two common measures for evaluating a company’s market position are market share and price–earnings (PE) ratio. Also consider all other quantitative data that is relevant to the case, such a brand strength, employee satisfaction, or innovation.

Bibliography

Certo, S. T., Jeon, C., Raney, K., & Lee, W. (2024). Measuring what matters: Assessing how executives reference firm performance in corporate filings. Organizational Research Methods, 27(1), 140–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/10944281221125160

Marketing Business Network. (2019, March 18). What is Organizational Performance? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLXuPgbagJY

3.5 Use a Range of Measures to Address the Complexity of Organizational Performance

Analyzing firm performance is crucial in strategic management, as leaders need to understand how well their organization is performing to determine if any adjustments are necessary. However, there are many ways to measure performance, and opinions vary on which metrics matter most. The complexity lies in not just choosing the right measures but also interpreting outcomes, which may not always reflect the quality of decisions made. Sometimes, good decisions can lead to poor results due to unexpected circumstances, such as external crises. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted many solid strategies that were previously thought to position organizations for success.

Using a range of performance measures and benchmarks is essential, as each provides different perspectives on how the organization is functioning. Without considering multiple angles, organizations risk missing key insights, which can lead to a skewed understanding of their true performance. To get an accurate picture, leaders must analyze performance from a variety of perspectives, ensuring they grasp both the strengths and weaknesses of their organization’s progress.

With so many potential performance metrics and benchmarks, understanding an organization’s performance can feel overwhelming. A study of restaurant companies’ annual reports, for example, identified 788 different combinations of performance metrics and benchmarks used within just that one industry in a single year (Short & Palmer, 2003).

Leaders analyze their firm by evaluating their current position, focusing on trend examination, and comparing themselves with industry benchmarks or competitors. For example, return on assets (ROA) measures how effectively a company turns its assets into profit. A high ROA suggests efficient asset use, while a low or negative ROA signals inefficiency. This analysis goes beyond financial metrics, incorporating other performance indicators like product quality, employee satisfaction, retention, productivity, and customer satisfaction. For instance, Software as a Service (Saas) is a cloud-based software delivery model where applications are hosted by a service provider and made available to users over the internet. Instead of purchasing and installing software on individual computers or servers, users subscribe to the software on a pay-as-you-go basis, often through monthly or annual plans. In SaaS companies like Netflix or Steam, monthly active users (MAU) is a crucial metric. Assessing various factors from multiple angles enables companies to gauge their overall performance.

Figure 3.5 shows a few additional key performance measures that are helpful when analyzing a company’s organizational performance.

| Metric | Formula/Definition | Purpose | Example use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly active users (MAU) | Total individual users engaging with the service in a month | Tracks customer engagement and product stickiness | Netflix monitors MAU to gauge customer activity. |

| Customer acquisition cost (CAC) | Total cost of acquiring new customers / Number of new customers | Measures the efficiency of customer acquisition | Steam evaluates CAC to optimize marketing spending. |

| Churn rate | (Customers lost during a period / Total customers at the start) × 100 | Identifies customer retention issues | Spotify analyzes churn to improve customer retention. |

| Lifetime value (LTV) | Average revenue per user (ARPU) × Average customer lifetime | Assesses the total value a customer brings | Slack uses LTV to understand long-term profitability. |

| Recurring revenue | Revenue from subscription services | Tracks stable, recurring income | Dropbox measures monthly recurring revenue (MRR). |

| Retention rate | (1 – Churn Rate) × 100 | Measures customer loyalty over time | Zoom focuses on retention to maintain a steady user base. |

Figure 3.5: Key measures for organizational performance

When you analyze organizational performance as part of conducting a case analysis, you use a range of measures, requiring a thorough knowledge of the case or company to select the measures that will be most useful. This also requires judgment.

When you analyze organizational performance as part of conducting a case analysis, you use a range of measures. Selecting the most useful measures requires a thorough knowledge of the case or company. It also requires judgment. Competence with the measures in figure 3.5 is essential to conducting an analysis of a firm for a case analysis.

3.6 Analyze a Firm’s Balanced Scorecard

Understanding organizational performance requires a multidimensional approach. Just as a pilot must monitor multiple gauges, such as altitude, airspeed, and fuel level, managers must track various performance metrics to ensure their organizations stay on course. While various financial performance measures are essential indicators, they are only one component of the bigger picture.

To help managers assess performance beyond just financial measures, Harvard professors Robert Kaplan and David Norton developed the balanced scorecard. This tool encourages a broader evaluation of an organization’s performance by focusing on multiple key areas. The balanced scorecard framework emphasizes a balance between financial indicators and other critical measures that influence long-term success.

The balanced scorecard suggests that managers track performance across four perspectives: financial, customer, internal business processes, and employee learning and growth. We reviewed the financial measures in section 3.4. Here we focus on the additional measures in the balanced scorecard: customer measures, internal business processes measures, and employee learning and growth measures.

Analyze Customer Measures

Customer measures reflect how well a company attracts, satisfies, and retains customers. These measures answer the question “How do customers view us?” Examples include metrics like new customer acquisition rates, customer satisfaction scores, and repeat customer percentages.

For instance, Amazon emphasizes customer retention by offering services like Amazon Prime, which encourages loyalty through faster shipping, exclusive content, and personalized shopping experiences. Additionally, Amazon gathers extensive customer data to anticipate consumer needs and adapt its offerings accordingly.

Analyze Internal Business Process Measures

Internal business process measures focus on organizational efficiency and answer the question “What must we excel at?” Internal business process measures include production times, delivery efficiency, and new product development speed.

For example, Toyota’s commitment to lean manufacturing focuses on reducing waste in its production processes. By streamlining assembly lines and improving supply chain coordination, Toyota continuously works to reduce the time it takes to manufacture vehicles while maintaining quality standards.

Analyze Learning and Growth Measures

Learning and growth measures provide insights into how an organization can continue to innovate and create future value. These metrics answer the question “Can we keep improving and adding value?” They often focus on employee development, innovation capabilities, and adapting to changing market conditions.

A company like Google, for example, prioritizes learning and growth by offering employees continuous opportunities for training and skill development. This not only keeps the workforce agile and innovative but also ensures that the company remains competitive in a fast-evolving tech landscape. Metrics in this category might include the number of new technologies introduced or the percentage of employees who undergo skill upgrades annually.

| Scorecard dimension | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Financial measures | How a firm is performing financially | Return on assets (ROA) Return on equity (ROE) Return on investment (ROI) Stock price Profits |

| Customer measures | How well a company attracts, satisfies, and retains customers | Number of new customers Number of repeat customers Percentage of repeat customers |

| Internal business process measures | How efficient the organization is | Production times Delivery efficiency New product development speed Speed serving a customer |

| Learning and growth measures | How a business can continue to innovate and create future value | Average number of new skills learned by each employee every year |

Figure 3.6: Analyzing organizational performance using the balanced scorecard

Complete the section titled “Balanced Scorecard” in the organizational performance analysis instrument.

Adding the measures considered in the balanced scorecard to those reviewed in the preceding sections offers a more thorough analysis of organizational performance.

Application

- The balanced scorecard provides a well-rounded view, helping managers understand where the organization stands and where improvements can be made. Similarly, individuals can apply this framework to evaluate their personal performance and growth across these same dimensions. Complete the following table for yourself.

| Scorecard dimension | Ask yourself |

|---|---|

| Financial measures | After graduation, what are my initial strategies to improve my personal wealth? Do I have student loans to repay? Do I have cash reserves, for example in a savings account? Do I have good credit and the ability to assume new debt to start a business or buy a home? Do I have current investments? What is my strategy to begin saving for retirement? |

| Customer measures | How strong is my professional network? How might I strengthen this and use it more effectively? What contacts can I make and strengthen while I am still attending university? How can I use my online professional network more effectively? |

| Internal business process measures | What have I learned from my university education and current work experience about completing work efficiently to a high standard? How has the time it takes me to complete assignments and work tasks improved? How could I improve this time further? What is my plan to accomplish this? What have I learned about myself when working with others and in teams? How could I improve my teamwork further? What is my plan to accomplish this? |

| Learning and growth measures | What new skills do I plan to develop now for the future? What licenses and certifications do I plan to obtain? Am I planning to earn a graduate degree? What growth and development goals do I have that relate to living a well-rounded life that may indirectly influence my career, such as emotional, mental, behavioral, and physical health goals or hobbies and friendships? |

Figure 3.7: Apply the balanced scorecard to yourself

The balanced scorecard offers a comprehensive framework for executives to evaluate their organization’s achievements across four critical dimensions: financial, customer, internal processes, and learning and growth.

Bibliography

Jargon, J. (2009, August 4). Latest Starbucks buzzword: “Lean” Japanese techniques. The Wall Street Journal, A1. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB124933474023402611?reflink=desktopwebshare_permalink

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard: Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, 70(1), 70–79. https://hbr.org/1992/01/the-balanced-scorecard-measures-that-drive-performance-2

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (2007, July–August). Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic management system. Harvard Business Review, 85(7).

Levy, S. (2011). In the plex: How Google thinks, works, and shapes our lives. Simon & Schuster.

Miller, C. (2010, June 15). Aiming at rivals, Starbucks will offer free Wi-Fi. The New York Times, 1B.

Norreklit, H. (2000). The balance on the balanced scorecard – A critical analysis of some of its assumptions. Management Accounting Research, 11, 65–88.

Short, J. C., & Palmer, T. B. (2003). Organizational performance referents: An empirical examination of their content and influences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 90(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00530-7

Starbucks. (2011). Our company. Starbucks. http://www.starbucks.com/about-us/company-information/mission-statement

3.7 Competitive Advantage

Although financial metrics like accounting measures and stock market returns provide insight into a firm’s short-term performance, they often fail to capture long-term success. These indicators can be misleading, as they are influenced by random market fluctuations. A company might experience a stroke of good fortune that results in high profits despite having a weak strategic position. On the other hand, a company with solid business fundamentals may suffer temporary setbacks and report disappointing profits. Another limitation of relying solely on these measures is that some companies, especially in growth phases, intentionally reinvest profits to fuel future expansion. This means their financial statements may not reflect their true health, even if they are thriving.

In strategic management, the focus often shifts from these financial measures to the concept of competitive advantage. This can be better understood through economic value creation (EVC), a concept that measures the difference between what a customer is willing to pay for a product (WTP) and the cost of producing that product.

EVC = WTP – Cost

In this equation, WTP is the maximum amount a customer would pay, while cost represents the expense the firm incurs to produce the product. The price a consumer actually pays is not included in this calculation.

Economic value creation can vary between companies, even when they sell similar products. This is because production costs and customers’ willingness to pay may differ from one firm to another. Consequently, some firms generate more economic value than their competitors, leading to differences in competitive standing.

A company is said to have a competitive advantage when its economic value creation exceeds that of its competitors. For example, if Firm A and Firm B produce similar goods, but Firm A creates more economic value (either through lower production costs, higher customer willingness to pay, or both), then Firm A holds a competitive advantage over Firm B. The magnitude of this advantage is the difference in the economic value created by each firm.

Competitive advantage is valuable for several reasons. Unlike profits and stock prices, which are influenced by market volatility, competitive advantage reflects deeper, more stable dynamics. If a firm increases its competitive advantage, it means either its costs have decreased, consumers’ willingness to pay has increased, or both, signaling true strategic improvement.

Additionally, competitive advantage accounts for the success of firms that reinvest their earnings; a company might report minimal accounting profits because it reinvests heavily in innovation or product development, yet it can still have a strong competitive position if its economic value creation remains high. For example, if Firm A reinvests most of its profits back into the business, it may report low accounting profits, but its competitive advantage could grow, as customers see more value in its product.

In practice, economic value creation is a more widely used and recognized concept than similar measures like economic value added (EVA), especially when discussing competitive advantage in strategic management. EVC focuses more directly on the relationship between customer value and production costs, making it a useful tool for understanding long-term strategic success.

Competitive advantage is the unique characteristics and capabilities of a firm that allow a firm to outperform its competitors.

In analysis carried out for strategic management, the focus often shifts from financial measures to the concept of competitive advantage. A company is said to have a competitive advantage when its economic value creation exceeds that of its competitors. Competitive advantage is the unique characteristics and/or capabilities of a firm that allow a firm to outperform its competitors. This advantage can be better understood through economic value creation (EVC), a concept that measures the difference between what a customer is willing to pay for a product (WTP) and the cost of producing that product (EVC = WTP – Cost).

Bibliography

Barney, J., & Hesterly, W. (2014). Strategic management and competitive advantage (5th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

Christensen, C. M. (2001). The past and future of competitive advantage. Sloan Management Review, 42(2), 105–109.

Peteraf, M. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 171–180.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. Free Press.

Christensen, C. M. (2001). The past and future of competitive advantage. Sloan Management Review, 42(2), 105–109.

3.8 Conclusion

By analyzing a wide range of areas related to organizational performance in this chapter, you are now able to provide a more comprehensive analysis of a firm’s organizational performance. The process begins with analysis of a firm’s mission, purpose, vision, and values. When analyzing organizational performance data, it is useful to consider a wide range of performance measures and benchmark measures to ensure you capture a thorough and robust picture of the firm. Analyze a firm’s financial position, its market position, and other relevant quantitative measures. Analyze a company’s balanced scorecard, including customer measures, internal business process measures, and employee learning and growth measures. This thorough review of an organization’s performance supports a more holistic view of their operations and informed evidenced-based decisions that promote sustained success. This approach helps managers understand where the organization stands and where improvements can be made. Analyzing a firm’s organizational performance produces analysis that relates to both the external and internal environments of the company. A company has a competitive advantage if its economic value creation exceeds that of its competitors. Competitive advantage reflects deeper, more stable dynamics.

Analyzing a firm’s organizational performance is the first step in case analysis. In the next chapter, we turn our attention to analyzing a company’s external environments.

Use these questions to test your knowledge of the chapter:

- Describe mission, purpose, vision, and values and how they are similar and distinct. Do companies always define each one? Discuss the most useful way to approach these when you conduct a case analysis.

- Explain performance measures and performance benchmarks. Give an example of each, and explain how your examples illustrate each.

- Review figure 3.4 to ensure you understand how to use each measure in case analysis. Test your knowledge by writing down each ratio and filling in the type of measure, the formula, and its purpose without referring to the figure. If there are any areas you need to study further, we encourage you to do this now, as they will be highly useful throughout the rest of the course.

- Describe market share and PE ratio. Explain how they are used to analyze a firm’s market position.

- What other types of relevant quantitative data may be useful when you conduct a case analysis? Explain their roles in case analysis.

- Discuss why using a range of measures is important when you analyze a case.

- Review figure 3.5 to ensure you understand how to use each organizational performance measure in case analysis. Test your knowledge by writing down each metric and filling in the formula and its purpose without referring to the figure. If there are any areas you need to study further, we encourage you to do so now.

- Describe what a company’s balanced scorecard measures and why this is a useful tool. Explain how considering alternative measures in addition to financial measures is useful and how this gives a broader measure of an organization’s performance.

- Discuss competitive advantage. Explain the concept, the formula, and its role in strategic management.

You are now competent at analyzing a firm’s organizational performance. Congratulations!

Figure Descriptions

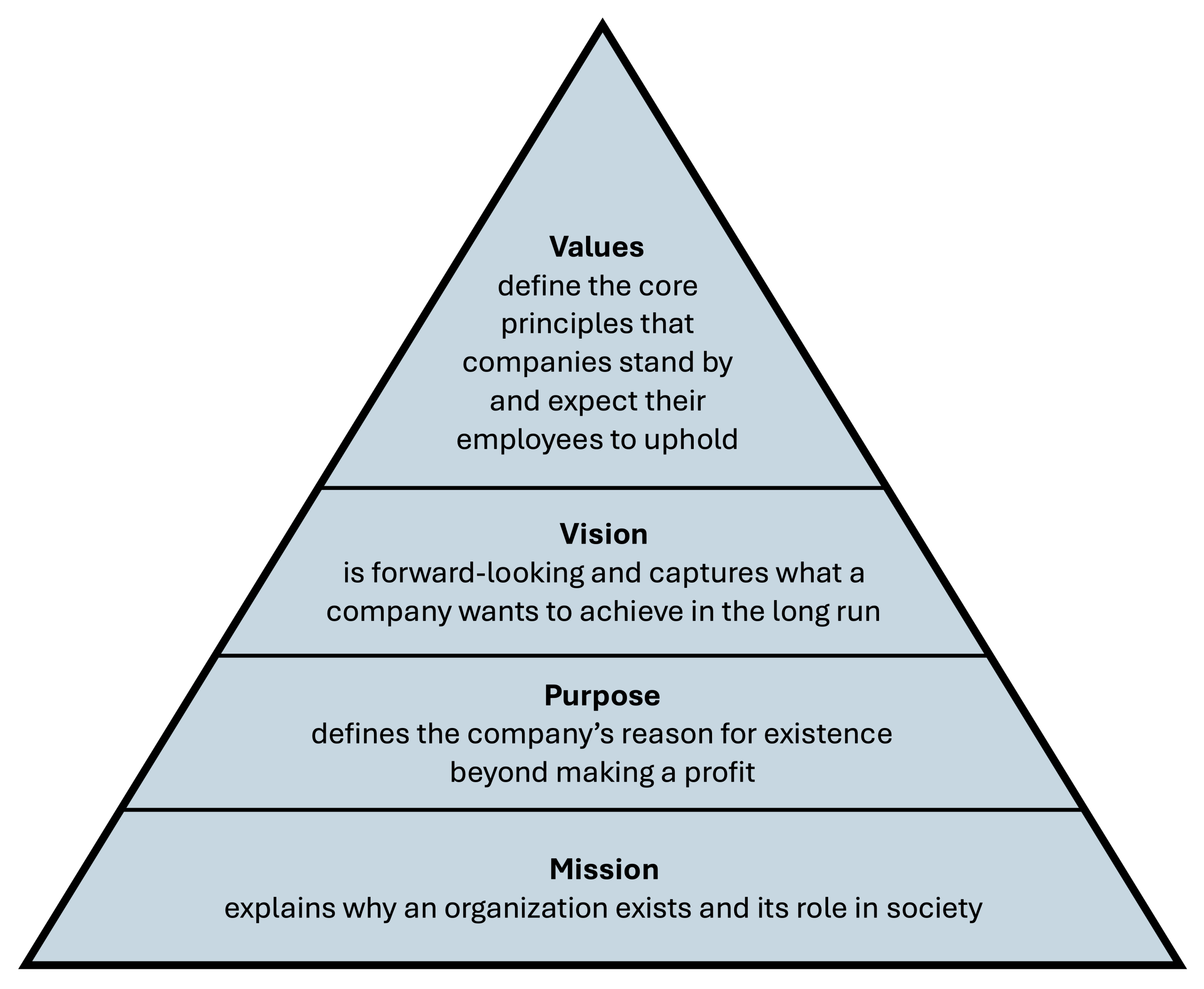

Figure 3.3: Blue pyramid divided into four horizontal sections. From top to bottom, the sections are labeled values, vision, purpose, and mission. Values define the core principles that companies stand by and expect their employees to uphold. Vision is forward-looking and captures what a company wants to achieve in the long run. Purpose defines the company’s reason for existence beyond making a profit. Mission explains why an organization exists, and its role in society.

Figure References

Figure 3.1: Peloton. Steve Jurvetson. 2017. CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peloton_HQ_reception_area.jpg

Figure 3.3: Analyze mission, purpose, vision, and values. Kindred Grey. 2025. CC BY.

Line of sight means there is a direct and clear logic connecting two or more concepts or ideas.

Congruence means there is a one-to-one relationship between two or more things. In case analysis, it refers to one-to-one reconciliation between steps in the case analysis process or across an entire strategic analysis.

A mission statement explains why an organization exists.

A firm’s purpose statement articulates its reason for existence beyond just profit-making.

A vision statement is a forward-looking or aspirational statement that captures what a company or organization wants to achieve in the long run.

Value statements define the core principles that companies stand by and expect their employees to uphold.

Performance measures are metrics used to track an organization’s progress, such as profits, stock prices, or sales figures.

Performance benchmarks are standards or reference points used to evaluate an organization’s metrics by comparing them to historical data, industry standards, or the performance of competitors.

Stock price reflects how investors perceive a company’s worth, making it a fundamental metric for market value.

Earnings per share is a metric that reflects how much profit is attributable to each share of stock, which is crucial for assessing a company’s value from an investor’s perspective.

Shares outstanding refers to the total number of a company’s shares currently held by all its shareholders.

Share price is the current market price of a single share of a company’s stock, determined by supply and demand in the stock market.

Market value measures indicate the overall value of a company as perceived by investors in the market. These metrics help assess the company’s worth based on its stock price and shares outstanding.

Net credit sales are the total sales a company makes on credit, minus any returns, allowances, or discounts.

Example: If a company has $100,000 in credit sales and allows $5,000 returns and discounts, the net credit sales would be $95,000.

The average amount of money owed to a company by its customers over a period, calculated by averaging the beginning and ending accounts receivable balances.

Example: If a company’s beginning accounts receivables $30,000 and its ending accounts receivable is $50,000, the average accounts receivable would be ($30,000 + $50,000)/2 = $40,000.

The cost of goods sold represents the direct costs of producing goods sold by a company, including materials and labor directly involved in production.

Example 1: For a bakery, COGS includes the cost of flour, sugar, and wages for the bakers.

Example 2: If a company manufactures bicycles, its COGS would include expenses for materials, labor, and manufacturing over-head used to produce the bicycles sold.

The typical amount of inventory a company holds over a period, calculated by averaging the beginning and ending inventories for that period.

Example: If a company’s beginning inventory is $50,000 and its ending inventory is $70,000, the average inventory would be ($50,000 + $70,000)/2 = $60,000.

Efficiency ratios assess how well an organization or individual manages resources. High efficiency means getting more out of assets, while low efficiency indicates waste or poor resource management.

Return on investment describes how effectively a company generates profit relative to the cost of investments, which ties directly to profitability.

Shareholder equity represents the ownership interest of shareholders in a company, calculated as the difference between a company’s total assets and total liabilities.

Example: If a company has $1 million in assets and $600,000 in liabilities, its shareholder equity would be $400,000.

Net profit is the amount of income remaining after all expenses, taxes, and costs have been subtracted from total revenue. It represents the company’s final profit.

Example: If a company’s total revenue is $100,000 and total expenses are $80,000, the net profit is $20,000.

Net revenue is the total revenue after subtracting returns, allowances, and discounts. It represents the actual income from sales.

Example: If a company’s total revenue is $50,000, but it gave $5,000 in discounts, the net revenue would be $45,000.

Gross profit refers to the revenue remaining after subtracting the cost of goods sold (COGS). It shows how much a company earns from its core operations before other expenses.

Example: If a company earns $100,000 in sales and its COGS is $60,000, the gross profit is $40,000.

The total income generated from sales of goods or services before any expenses are deducted.

Example: If a store sells $150,000 worth of products in a month, that amount is its total revenue for that month.

Profitability ratios focus on the ability to generate profit. These measures show how well an organization or individual is able to grow their income over time, which is essential for sustainable success.

A company’s total liabilities are made up of all its debts and financial obligations, such as loans taken from a bank.

A company’s total assets are everything it owns that has economic value, including both current and long-term assets. Buildings owned by the company, alongside cash, equipment, and inventory, all contribute to total assets.

Leverage measures evaluate the level of debt in relation to equity. These ratios show how much of a company’s or individual’s assets are financed by debt, providing insight into financial stability and risk.

Current assets are expected to be converted into cash or used within one year, such as cash in a company’s bank account.

Obligations or debts a company must pay within one year, such as accounts payable, which represents money owed to suppliers.

Liquidity measures help assess if an organization or individual can meet short-term obligations. For example, can a company or a person pay off immediate debts with readily available cash?

Balanced scorecard is a management system that evaluates a company using four measures: financial measures, customer measures, internal business processes measures, and employee learning and growth measures.

Customer measures on a balanced scorecard evaluate how well a company attracts, satisfies, and retains customers. Customer measures include new customer acquisition rates, customer satisfaction scores, and repeat customer percentages.

Internal business process measures are an element of the balanced scorecard that measure organizational efficiency. Internal business process measures include production times, delivery efficiency, and new product development speed.

Learning and growth measures are an element of the balanced scorecard that measure how an organization can continue to innovate and create future value. Learning and growth measures focus on employee development, innovation capabilities, and adapting to changing market conditions.

Competitive advantage refers to the unique characteristics and capabilities of a firm that allow it to outperform its competitors in economic value creation.