5 Inclusive Teaching

Stacy K. Vincent and Donna Westfall-Rudd

Setting the Stage

In the early 1970s, Dr. Henry Schmitt asked, “Will middle-class White Anglo-Saxon Protestant vocational agriculture teachers accept minority youth and adults enrolled in vocational education in agriculture?” (1971). Schmitt posed this question to agricultural education institutions soon after the desegregation of public schools, the creation of consolidated school districts, and the merger of the New Farmers of America (NFA) and the Future Farmers of America (FFA). His corresponding study focused on designing “professional experiences that will prepare teachers for urban and rural minority children, youth, and adults” (p. 20). The chapter is grounded in the multicultural education literature (Banks, 2008) that coincidentally began to emerge at the same time Dr. Schmitt published his dissertation. Since Schmitt’s study, secondary and postsecondary agricultural educators have had sporadic discussions about the learning needs and experiences of underrepresented minority students in local programs. Still today, we, as educators, face the challenges of including all students in local agricultural education experiences.

Objectives

The purpose of this chapter is to provide readers with the opportunity to:

- Discover the importance of developing knowledge of individual cultures and identities to support and engage students in agricultural education.

- Investigate how to connect intersecting student and teacher identities within agricultural education courses to obtain multicultural autonomy.

- Apply multicultural and inclusive teaching practices in an agricultural education classroom.

Introduction

Unfortunately, society constructs an identity about an individual without ever getting to know them. For some individuals, this may be a positive construction of identity; however, it may never reflect who one truly is, nor how they want to be known. Social identifiers, as listed in table 5.1, are dispositions that are integrated into one’s identity and therefore dictate their interactions with other individuals. On the other hand, personal identifiers are distinguished characteristics for which the individual personally recognizes who they are and whom they associate with based on commonalities.

Overview

Addressing the needs of all students can seem like a daunting task for early-career educators. This chapter is intended to help educators begin the process of purposefully planning courses, FFA opportunities, and Supervised Agricultural Experiences (SAEs) to be inclusive of all student cultures and identities that may be present in the local program. While this may initially seem too big of a challenge, this chapter intends to offer a foundation of knowledge and recommended practices to support the implementation of multicultural and inclusive teaching practices.

| Social Identifiers | Personal Identifiers |

|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | What Makes You Unique |

| Language | Talents |

| Gender Identity | Likes |

| Geographic Location | Peculiarities |

| Socioeconomic Status | Ways of Doing Things |

| Religion | Personality Type |

| Age | Introvert/Extrovert |

| Sexual Orientation | Skills |

| Education | Passions/Compassions |

| Body Type | |

| Ability | |

| Family Structure |

Table 5.1: Social and personal identifiers.

Multicultural Autonomy

Are we good teachers? Of course, we want to be good teachers and desire to make a positive difference for students. But what does it take to make a positive difference in the lives of students? Though perhaps surprising to our noneducation friends, we would all agree that simply providing the details for learning a particular task does not reflect a methodology that inherently creates a positive life-long connection.

When examining our reason for considering the profession of educating others about agriculture, our inspiration comes from a myriad of approaches, such as respect toward a previous instructor, a passion for helping youth, or our deep inquiry within the content area. Coincidentally, whichever approach, our vision of who we will deliver the content to is skewed by what we know. To simplify this understanding, let’s examine your palette. Let’s say that your entire life, the only meal you had consumed and visually recognized was pizza; how could you envision, understand, and relate to the taste, smell, and visual of sushi? It cannot happen. The same visualization for our attempt to educate others is biased toward only what we have seen, experienced, and exposed ourselves to.

This process is called the Apprenticeship of Observation (Lortie, 1975). We gain efficacy in our ability (in this context, teaching) based on our observations and experiences in the past. Therefore, it is difficult to identify what our classroom, and who the students we will educate, will become if we have never exposed ourselves to anything different. While the diversification of exposure does not predict your ability to be a quality educator, it limits the overall volume and diversification of whom you positively impact.

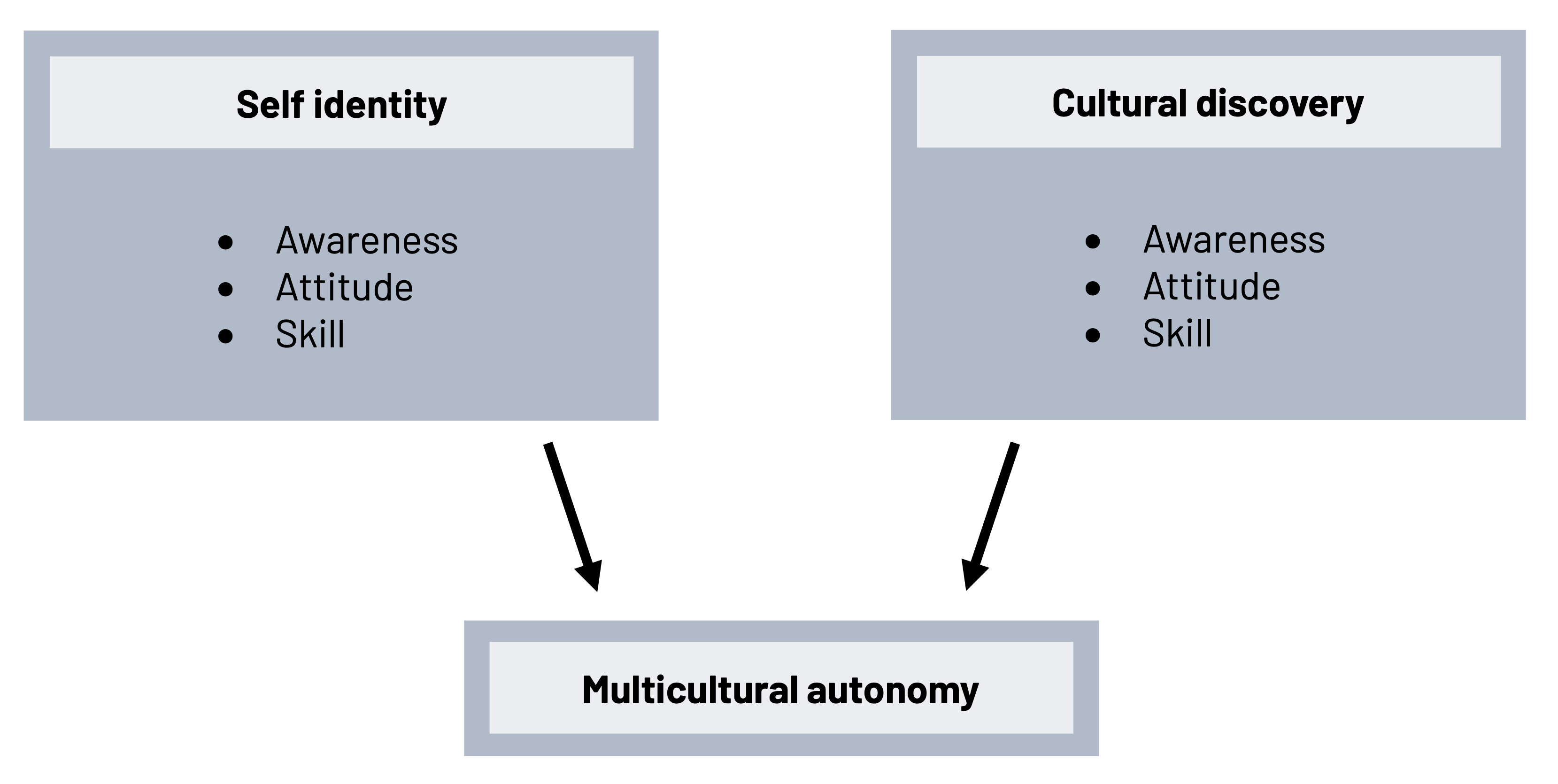

But what if we were knowledgeable in the pizza community as well as the sushi community? And what if the more we expand in the pizza and sushi community, our awareness, knowledge, and attitude grow and expand? Now we have the ability to connect the two communities so they can find ways to work together. Similarly, a teacher can gain students’ trust from various cultural backgrounds without letting go of their own identity. In doing so, we must immerse ourselves in the different cultural communities to expand our competence levels. When an individual can competently work and communicate with multiple cultural groups and be accepted within the groups, we call this ability multicultural autonomy (Vincent & Westfall-Rudd, 2022). The individual would not have to change their core identity to fully obtain multicultural autonomy. An individual cannot simply wake up and determine that they have multicultural autonomy. This concept takes work and patience and is ongoing. To reach the point that autonomy is possible, a teacher must begin with self-reflection of (a) awareness, (b) attitude, and (c) skills. For a visual of multicultural autonomy, see figure 5.1.

Self-Awareness

Harris (2001) recognized that a lot goes into the identity of self. We are labeled and identify ourselves, whether it is correct or not, by social identity (i.e., race/ethnicity, language/dialect, religion, age, sexual orientation, educational level, body type, socioeconomics, ability, family structure, geographic location, etc.). Social identifiers can be helpful and harmful in the perceptions of those around us. One of this chapter’s authors, Stacy, recalls a time social identifiers impacted him:

“I recall, as a child, on a weekend trip out of my home state, my parents sent me to get extra towels from the hotel staff. The hostess loved my accent, and when she discovered I was from Kentucky, she looked over the counter and said, “Wow, you have shoes!” My social identity, in this instance, personified a negative stereotype.”

However, our self-identity also encapsulates an area many individuals never see or value if it is not recognized in our workplace, also known as personal identity. Our identity (i.e., talents, likes, peculiarities, personality, political beliefs, ways of doing things, introversion/extroversion, skills, uniqueness, etc.) also plays a major role in defining who we are.

Before we can ever have more than a minimal impact in our classroom, we must become aware of who we are. While our lives continue to experience memories and our interactions diversify, so should our continued reflection and awareness, which inadvertently changes our self-identity.

As teenagers, we grew in our self-awareness, but it didn’t keep adults from telling us to check our attitude. It is good advice (although probably not in the tone or format they were referring to). Gay and Kirkland (2003) believe it is crucial to self-reflect on our attitude during critical cultural moments. These critical moments often occur in the presence of major global events that may be happening. Although we may ignore many of the issues, we must take a second to reflect on our attitude as to why we are choosing to ignore it. The same reflection must occur when we are experiencing anger, sadness, excitement, happiness, and disappointment (Vincent & Drape, 2019). It is very important to note that the reflection of these attitudes is explicit and should not be confused with implicit attitudes (Benaji & Greenwald, 2013). Still, this chapter will not be expanding into it.

Self-Attitude

As Stacy was entering high school, the rapper (at that time, now better known as an actor) Ice Cube, released a song titled “Check Yo Self,” and one of the lines that always stuck with him in the song was So come on and chickity check yo self before you wreck yo self. Cube (as Stacy refers to him, because they’re buds) understood self-identify’s second construct: self-attitude. In this area, we begin to examine our attitudes.

It is not difficult to determine our attitude by simply taking a stroll through our social media outlets and examining what we like, share, post, read, and follow when a topic of controversy comes across our feed. Now, we may not follow a lot on social media, but we do speak with colleagues on occasional topics or read articles regarding the mishandling of particular issues. In these instances, do you ever find yourself reading the comments that some brave souls posted? During your read, you will find yourself shocked by the ludicrous statements or nodding your head to the realization that someone else believes the same thing. At that instant, we should begin to restate, reflect upon, or simply rap Ice Cube’s lyrics and simply “check yo self.”

Attitude is crucial in how others perceive us and how we interpret someone else’s attitude. Of course, we all have our peeves, but by not keeping your attitude in check, you begin to “wreck yo self.” Let’s go through an example together.

Silvia is having a difficult day on her way to school. There are relationship issues between her and her boyfriend, and her mother just told her that she could not stay after school due to parental assistance needed once she returns home to her adolescent siblings. At the same time, you are having a difficult day as well. You arrived a few minutes late and spilled coffee on your pants a few minutes before class began. In expressing herself only as she understands, Silvia walks into your classroom, slams her books on her desk, and storms out, muttering explicit words (also from an Ice Cube song).

How do you react? Do you go after her, express your feelings toward her methods, and ask that she share her feelings with the school principal? Do you take a second to realize that you (a) have a coffee-stained pair of pants and (b) are not in the right attitude to come to grips with how her day is crumbling? Most of us have seen how option one plays out. The teacher and the student go into an embarrassing shouting match where the student, the student’s guardian, and the student’s siblings will have a very bad day, and you end up on a video blasted on social media. Did you win? Maybe you got a shot in the ego arm, but you gained nothing in your ability to examine your self-attitude and continued to make impulse decisions no matter the spirit of your attitude. Honestly, attitude can be an endangering or a strengthening tool.

Self-Skill

Before having a classroom of our own, we determine the teaching style that works best for us and the students we are teaching. How do we know, though? Of course, our peers tell us it was a great lesson, but they have had similar classes from the same professors and received the information exactly like you did. The students to whom we provided the lessons may have seemed engaged, but were they from the best practicum of classes with students who are passionate about the content? Even our professor could inform us that it was structurally a sound lesson, but they are now removed from the culture in the classroom that you are about to enter. Bottom line, the group that we have provided lessons to thus far reflects very similar awareness levels, attitudes, and cultural beliefs to those that we have; therefore, we have to ask ourselves “does our pedagogical skill work in a classroom of students who think, look, and behave differently than those coming from the cultures to which we have ourselves been exposed?” Sometimes, we never fathom the extent of this question until we enter our classroom.

Creating a Multicultural Agricultural Classroom

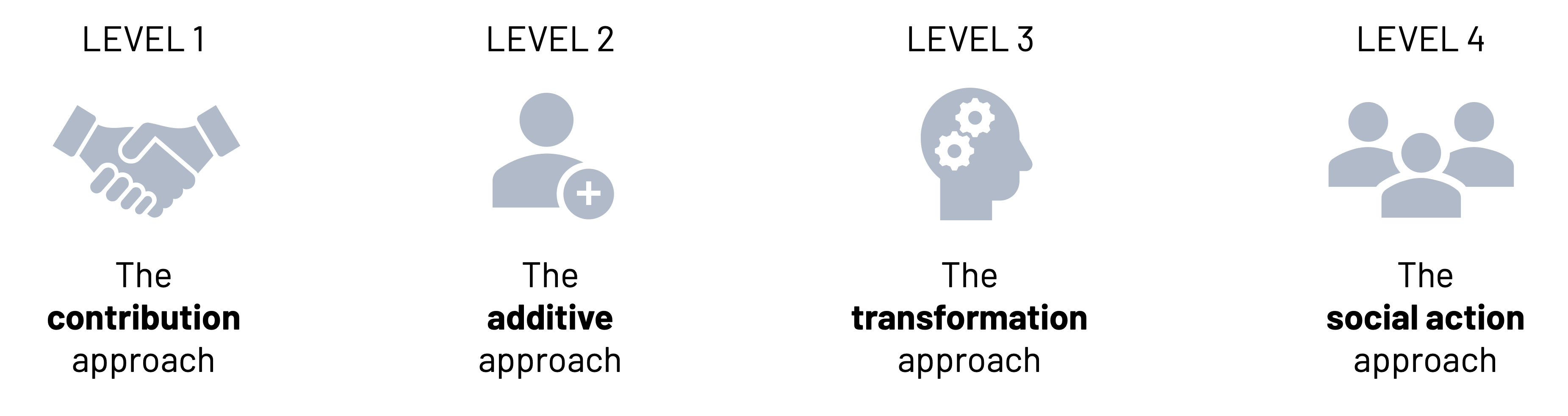

There are multiple approaches that a teacher considers as they craft their lessons for the upcoming school year. One of the most important approaches is developing a curriculum that encompasses a multicultural path. Banks (2008) introduced four levels to approaching a multicultural curriculum (see figure 5.2) that can provide a scaffolding on which teachers can build their pedagogical skills and knowledge when creating a multicultural classroom and agricultural education program.

Throughout the country, schools and classrooms are finding methods to integrate cultural differences inside and outside the community. One of the approaches, level 1, the contribution approach, occurs when teachers integrate holidays and cultural celebrations into the course activities, such as African American History Month, Cinco de Mayo, Women’s History Week, and Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. The contribution approach is an initial step that compliments the other three strategies, primarily focusing on heroes, holidays, and discrete cultural elements. In the agricultural education curriculum, teachers can incorporate these cultural items into many of the courses in a local program. (See table 5.2.)

| Subject | Level 1 Implementation |

|---|---|

| Floriculture | Introduce cultural holidays and images of floral designs seen in cultural holidays. |

| Animal Science | Identify the geographic origins of livestock breeds. |

| Food Science | Develop a bulletin board displaying the production and processing of foods specifically for various cultural markets to meet the diversity of cultural food traditions of holidays. |

Table 5.2: Contribution approaches in agricultural education.

Educators are also beginning to frequently use practices that reflect level 2, the additive approach (table 5.3). At this level, teachers add cultural content, concepts, and perspectives without implementing structural changes or adding a large amount of effort to the curriculum revision. Banks says, “The additive approach is often accomplished by adding a book, a unit, or a course to the curriculum without changing the framework” (p. 47). Although level 1 and level 2 are approaches that compliment effort, they do not challenge the curriculum, the cultural norms, or the thoughts or interpretation of the dominant culture.

| Subject | Level 2 Implementation |

|---|---|

| Introduction to Agriculture | • Integrate the history of agricultural practices of Native American cultures, including the origin of crop rotation and intercropping practices. • Integrate the history and movement of corn by Native communities from what is now called Central to North America. • Identify the history of crops originating in West Africa, including watermelon and peanuts. Break down the assumptions that only European settlers had the knowledge and skills to begin farming in North America. |

| Animal Science | • Have a discussion of enslaved West Africans chosen based on their animal husbandry experiences. • Have a discussion of animal husbandry practices from West Africa. |

| Food Science | • Examine the cuisine as it relates to global topography and geography—for example, the proximity of spicy food to the Equator. • Discuss how new food processing and preparation approaches were brought to the United States from West Africa. Dishes coined as Southern culinary cuisine, such as fried chicken, jambalaya, and barbecue, were first prepared by enslaved people. • Discuss how delicacies differ across the United States and the world. For example, “Cui,” or a Guinea pig, is a meat served on special occasions in Ecuador. • Examine the food processing requirements of different religions. |

| Leadership Development | • Encourage students to present speeches in their first language. |

Table 5.3: Additive approaches in agricultural education.

Level 3 fundamentally differs from the first two levels as it contains objectives that shift paradigms and question basic assumptions. By doing so, the curriculum allows students to see, hear, and comprehend different points of view. The level 3 transformation approach entails a structural change in the curriculum so that students are enabled to understand information from the perspective of diverse groups. Specifically, the aim of level 3 is to assist students in thinking critically and develop a skill set that empowers them to construct, document, and support their conclusions and generalizations. Table 5.4 provides examples of level 3 interaction in agricultural education.

| Subject | Level 3 Implementation |

|---|---|

| Landscape Architecture | Examine socioeconomic opinions by discussing “Which individuals desire a landscaped home?” Taking a community trip and visiting various neighborhoods of different socioeconomic levels allows students to see that similar care is put forth, but that financial earnings play a role in what is on display. Nevertheless, some plants, regardless of income level, have value or meaning to the owner; thus, landscaping is important to all income levels. |

| Animal Science | When exploring countries of origin, lead students to determining why an animal was brought to the United States. Which ethnic group decided the animal that would inhabit America? What diseases did it bring to the land and whom did these diseases affect? Which religion supported the movement of these animals? |

| Floriculture | During a floral identification lesson, engage students in identifying the country of origin for each of the major flowers sold in the United States. Use research and discussion to encourage students to determine the cost of each flower sold during its peak season and what an individual is paid to grow and harvest the flowers in the country of origin (e.g., roses grown in Ecuador). |

Table 5.4: Transformation approaches to agricultural education.

NOTE: As the curriculum moves into the transformation phase, the lesson becomes embedded and is fluid with what is being taught rather than a hard break to the curriculum.

When students begin to make decisions on important social issues by responding with action to help solve the problem, then the teacher has met level 4, the social action approach. We have the perfect opportunity for social action within agricultural education as our students are responsible for obtaining and managing an SAE project. In addition, agricultural education youth have the potential to be enrolled in our classes for multiple years, where social action can be built upon as students grow in their civic responsibility within their community. When the agriculture curriculum is being delivered in the social action approach (table 5.5), learning occurs, and proud moments are celebrated.

| Subject | Level 4 Implementation |

|---|---|

| General to the program | Students develop a comprehensive list of agricultural magazines from various ethnic backgrounds for the school library to purchase and display. |

| Landscape Architecture | Students develop an arboretum that entails plant information that engages readers to think about the pain and suffering that occurred for the plant to migrate from its country of origin to the United States. |

| Agricultural Business | Student create projects focused on investigating the impacts of farm labor laws and policies on the immigrant and nondocumented agricultural workforce. |

| Leadership Development | Because of the diversity of the membership, the chapter officers develop an end-of-the-year celebration or banquet that is inclusive of all religious and cultural considerations, taking care to consider the day of the week, avoid conflicts with all holidays, and ensure all are able to enjoy. Students choose public speaking topics that respond to social justice issues impacting members of the community and the agricultural industry of the region. |

| Agriculture Sales | Students work with the local farmer’s market so that the farmers are able to receive SNAP funding so low-income families can obtain fresh food. |

Table 5.5: Social action approaches to agricultural education.

Teaching Practices for Multicultural and Inclusive Agricultural Education Classrooms

Changing teaching practices to create inclusive teaching strategies requires us to reflect on our current practices and classroom environment intentionally. Then, considering what we see and understand about our teaching and the spaces in which we teach, we can try new ideas. Once implemented, we must be courageous and ask our students for feedback on our changes.

Planning

- Review all IEP and 504 plans early to embed student needs within the curriculum rather than making targeted accommodations that can “single out” students.

- Identify English Language Learner students and their level of proficiency. Place them near the front of the room so targeted communication can occur.

- Designate a “Food Drawer” for students whose hunger needs are not being met.

- Develop a predetermined seating chart to assist and encourage student interaction and engagement rather than targeting disciplinary control.

- Obtain flags from the country of origin of your students and display them throughout the classroom.

- Develop bulletin boards that display the interests of every student and deliver a message that the classroom embraces a SafeSpace environment.

- Identify religious holidays during the school year and add them to your calendar as a reminder to bring attention to them.

As teachers, we all know that what things we say and how we say them matters. Students see us as leaders and role models in our classrooms. Therefore, to have positive and appropriate communication in our classrooms, we must ensure we do our part to make it happen.

Communicating with Students

- As part of activities on the first day of class, ask students to respond to the following questions on a worksheet you provide or an electronic format appropriate to the course:

- What name would you prefer we call you?

- What is something about yourself that you are proud of?

- What would you like me to know about you?

- What concerns you most about this class?

- What is your favorite music genre?

- Always use a student’s preferred pronouns and apologize when you misspeak.

- Post your preferred pronouns.

- Ensure classroom images and resources include representation of diverse cultures, races, ethnicities, genders, and abilities.

- Learn the cultural communication practices of the students in your program.

- Engage students in cocreating the classroom expectations.

- Ensure materials are ADA compliant.

Building relationships with students and their families through home visits has been a tradition in agricultural education. Over time, in many communities, teacher visits for SAE project supervision have been diminished or removed. As most of us agree, this is not a desirable change. We recommend renewing our efforts to make home or job site visits to strengthen the connections between our students’ families and our agricultural education programs.

Building Relationships with Families

- Be an advocate for the student and bring parent requests to the attention of committee members during a 504 planning meeting.

- Constitute student praise calls rather than calls regarding demerits.

- Develop a bilingual monthly email to parents that discusses previous successes and upcoming events.

- Invite families to events and trips.

- Obtain funding for meal function events that alleviates the cost of attending (e.g., banquet tickets).

- Provide childcare opportunities for parents who desire to meet with you or attend a school event for your student.

Learning Confirmation

What would you do? Work with a colleague or a team of colleagues to discuss the following two case studies. How do you respond to the questions? Remember to provide a discussion that allows everyone to speak openly and be sure that to implement listening skills.

Case Study #1

A student wants to join the livestock team, has worked intently in class, and is passionate about the subject. They find out that practices are held after school, and if practices are missed more than once, it would result in the removal from the team. Unfortunately, the student cannot attend most practices because of their responsibilities. Living with only one parent, they must ride the bus with their younger siblings and watch them until their mom arrives.

Behind the scenes, the teacher is known to only allow teams of two males and two females OR four students all of one gender due to a philosophy of money “wasted” on hotel rooms that would only hold one person. Unfortunately, there are already three students of the opposite gender on the team, and while the student’s talent is just as good, if not better than the current team members, they choose not to inform the teacher of their interest.

- Does the student have a chance of making the team?

- What amendments can be made to assist the (a) teacher, (b) student, (c) student’s family, and (d) team members?

Case Study #2

A student (male, Muslim, and visually colorblind student) at the school has a very hectic schedule and enrolled in a floriculture course after hearing that it was a good class for students who needed a break from bookwork and desired a course where you could work with their hands.

It is the middle of the Ramadan holiday, and the subject is learning color patterns. On this particular day, the color wheel was the focus of the learning objectives, and the teacher began by saying, “All right ladies, using icing, food coloring, and sugar cookies; whoever correctly displays the color wheel will receive a pass on the next daily quiz.” Unfortunately, the bottles of food coloring were not labeled, and once the student was midway through the assignment, the teacher approached and said, “Are you even trying?”

Once the class is finished and the assignments are graded, the teacher allows the students to eat their colorful cookies. The student offered their cookie to someone else and the teacher asked why they would give away something so delicious. Once the student tells the teacher their belief, the teacher simply says, “Oh, one cookie won’t hurt you.”

- What were the three comments that could have created a microaggression?

- How could the three comments have been avoided?

- How will you ensure that you, and your classroom, are accepting of a student in a similar situation?

Applying the Content

Use the following questions to guide your development in establishing a more inclusive agricultural education program. Check them off when you have completed.

- Do you know which students have an IEP and/or 504 plan?

- Are your members comfortable attending an overnight trip with a student who identifies themselves in the LGBTQ+ community?

- Does the program have an activity to participate in the community during Martin Luther King Jr. Day?

- Does the officer team reflect the demographics of the school and agriculture education program?

- Would your community be supportive of the program if the chapter president was an ethnic minority?

- Do quiet students have a place in the program?

- Would a vegan student feel comfortable talking to you?

- Do you have a plan to help students who cannot read?

- What will be the out-of-pocket cost for students to attend your most expensive trip?

- Do you have alternative seating in your classroom for an obese student? Where will it be located?

- What percent of your events will be outside the school day?

- What percent of your students rely on bus transportation?

- Do you have a liaison to assist you in the pronunciation of your students’ names?

- What music will you allow to be played in your classroom?

- Have you set your calendar to recognize international holidays?

- Have you created a “wish list” of places to visit, or list of places already attended, on every continent? Do you already know where to add your experience or “wish list” to the curriculum being taught?

- Do you have a safe and secure area for students to maintain an SAE?

- Can you identify a student who needs shoes and find the resources to provide?

- Besides the school community, do you know of ethnic restaurants to expose your students to during a school trip?

Reflective Questions

- How do you describe your individual identity and cultural background?

- How do you use your identity and background to engage students in your classroom?

- What multicultural and inclusive teaching practices will you implement in your classroom this semester?

Glossary of Terms

- additive approach: At this level of changing the curriculum to be more inclusive of all students, teachers adds cultural content, concepts, and perspectives without structural changes and with minimal effort to the curriculum revision

- apprenticeship of observation: One gains efficacy in their ability to teach based only on observations and experiences in the past as students, not on training received or practical teaching experience

- contribution approach: Occurs when teachers integrate cultural traditions, such as holidays, celebrations, and traditions, into the course activities, physical classroom visuals, or attempting to recognize through a sensory such as music playing on a particular day

- culture: All the complex aspects of a person or group’s world experiences, including food, traditions, beliefs, habits of social interaction, environment, personal and social identity, music, and language

- inclusive teaching practice: Purposeful planning and implementation of teaching strategies that engage all students in the learning process regardless of ability, background, individual identity, or social status

- multicultural autonomy: When an individual can competently work and communicate with multiple cultural groups and be accepted within the groups, while maintaining comfortability as their own identified self

- multicultural autonomous agricultural educator: An educator who has the ability to connect two diverse cultural groups to the curriculum and find methods that allow the two cultural groups to collaborate and respect the differences that each brings to the collaboration

- personal identifiers: Distinguished characteristics for which the individual personally recognizes who they are and whom they associate with based on commonalities

- social action approach: The final stage of multicultural teaching reform where students gain curriculum knowledge while engaged/empowered to transform their gained knowledge to an action that helps their community regarding a social issue

- social identifiers: A traits or characteristics that an individual possesses, which are the basis for how others categorize themselves within social contexts and groups

- transformation approach: A structural change in the curriculum so that students are enabled to understand information from the perspective of diverse groups

Commonly Used Resources

- List of Agricultural Education Magazine issues relevant to diversity and inclusion:

- Boone, H. N. (Ed.). (2014). Preparing the next generation of leaders. The Agricultural Education Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.naae.org/profdevelopment/magazine/archive_issues/Volume87/2014_09-10.pdf.

- Boone, H. N. (Ed.). (2012). Serving students in agricultural education with special needs. The Agricultural Education Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.naae.org/profdevelopment/magazine/archive_issues/Volume84/2012_05-06.pdf.

- Cano, J. (Ed.). (2012). Enhancing diversity. The Agricultural Education Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.naae.org/profdevelopment/magazine/archive_issues/Volume79/v79i1.pdf.

- Ewing, J. C. (Ed.). (2018). Diversity and inclusion in agricultural education programs. The Agricultural Education Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.naae.org/profdevelopment/magazine/archive_issues/Volume90/2018%2005%20–%20May%20June.pdf.

- Parham, E., & Vincent, S. K. (2018). Now is the time: effective strategies to connecting with African American students. The Agricultural Education Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.naae.org/profdevelopment/magazine/archive_issues/Volume90/2018%2005%20–%20May%20June.pdf.

- Vincent, S. K. (2018). Let’s create Cinderella stories. The Agricultural Education Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.naae.org/profdevelopment/magazine/archive_issues/Volume90/2018%2005%20–%20May%20June.pdf.

- Vincent, S. K., Harper, T., & Tyler, Q. (2018). Are we truly serving all? keys to making a positive difference in the lives of all students. The Agricultural Education Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.naae.org/profdevelopment/magazine/archive_issues/Volume88/2016%2005%20–%20May%20June.pdf

- Parent-Teacher Conferences: Strategies for Principals, Teachers, and Parents Global Family Research Project, 2019

- Livermore, D. A. (2013). Expand your borders: Discover ten cultural clusters. East Lansing, MI: Cultural Intelligence Center, LLC

Figure Descriptions

Figure 5.1: Self identity includes awareness, attitude, and skill. Cultural discovery includes awareness, attitude, and skill. Together, self identity and cultural discovery make multicultural autonomy. Jump to figure 5.1.

Figure 5.2: Level 1: The contribution approach. Level 2: The additive approach. Level 3: The transformation approach. Level 4: The social action approach. Jump to figure 5.2.

Figure References

Figure 5.1: Multicultural autonomy growth model. Kindred Grey. 2023. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.2: Approaches to multicultural curriculum reform. Kindred Grey. 2023. Adapted under fair use from James A. Banks, “Approaches to Multicultural Curriculum Reform,” 2008. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review/vol3/iss3/5

References

Banks, J. A. (1993). Approaches to multicultural curriculum reform. In J. A. Banks & C. A. McGee Banks (Eds.), Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives (2nd ed.), 195–214.

Banaji, M. & Greenwald, A. (2013). Blindspot: Hidden biases of good people. Delacorte Press.

Cube, I. (1993). Check Yo Self [Song]. On The Predator [Album]. Priority Records.

Gay, G. (2003). Becoming multicultural educators: Personal journey toward professional agency. Jossey-Bass.

Gay, G., & Kirkland, K. (2003). Developing cultural critical consciousness and self-reflection in preservice teacher education. Theory Into Practice, 42(3), 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4203_3

Harris, R. P. (2001). Hidden voices: Linking research, practice, and policy to the everyday realities of rural people. Journal of Rural Social Sciences, 17(1), 1–11.

Lortie, D. (1975). Schoolteacher: A sociological study. University of Chicago Press.

Schmitt, H. E. (1970). A model for preparing secondary teachers of agriculture for minority populations. Journal of the American Association of Teacher Educators in Agriculture, 12(2), 20–29. http://doi.org/10.5032/jaatea.1971.02020

Vincent, S. K., & Drape, T. A. (2019). Evaluating micro expressions among undergraduate students during a class intervention exercise. Nacta Journal, 63(2), 133–139.

Vincent, S., & Westfall-Rudd, D. (2022, May 16–19). A Philosophical Approach to Obtaining Multicultural Autonomy as an Agricultural Educator. American Association for Agricultural Education National Conference proceedings, Oklahoma City, OK. https://aaea.wildapricot.org/resources/Documents/National/2022Meeting/2022AAAEPaperProceedings.pdf