1. Introduction to Strategic Management

Chapter 1 ensures that you understand and are able to apply the following key strategic management concepts:

- How the terms organization, business, company, firm, and industry are used in the textbook

- How the terms strategic management concepts and theories and analytical frameworks and tools are used in the textbook

- What strategic management is

- The analysis, formulation, implementation (AFI) framework

- Intended, deliberate, emergent, realized, and unrealized strategies

- Why strategic management is important

- The history of strategic management

- Contemporary critique of strategic management

- Why strategic management is valuable to you in all career settings and at all career stages

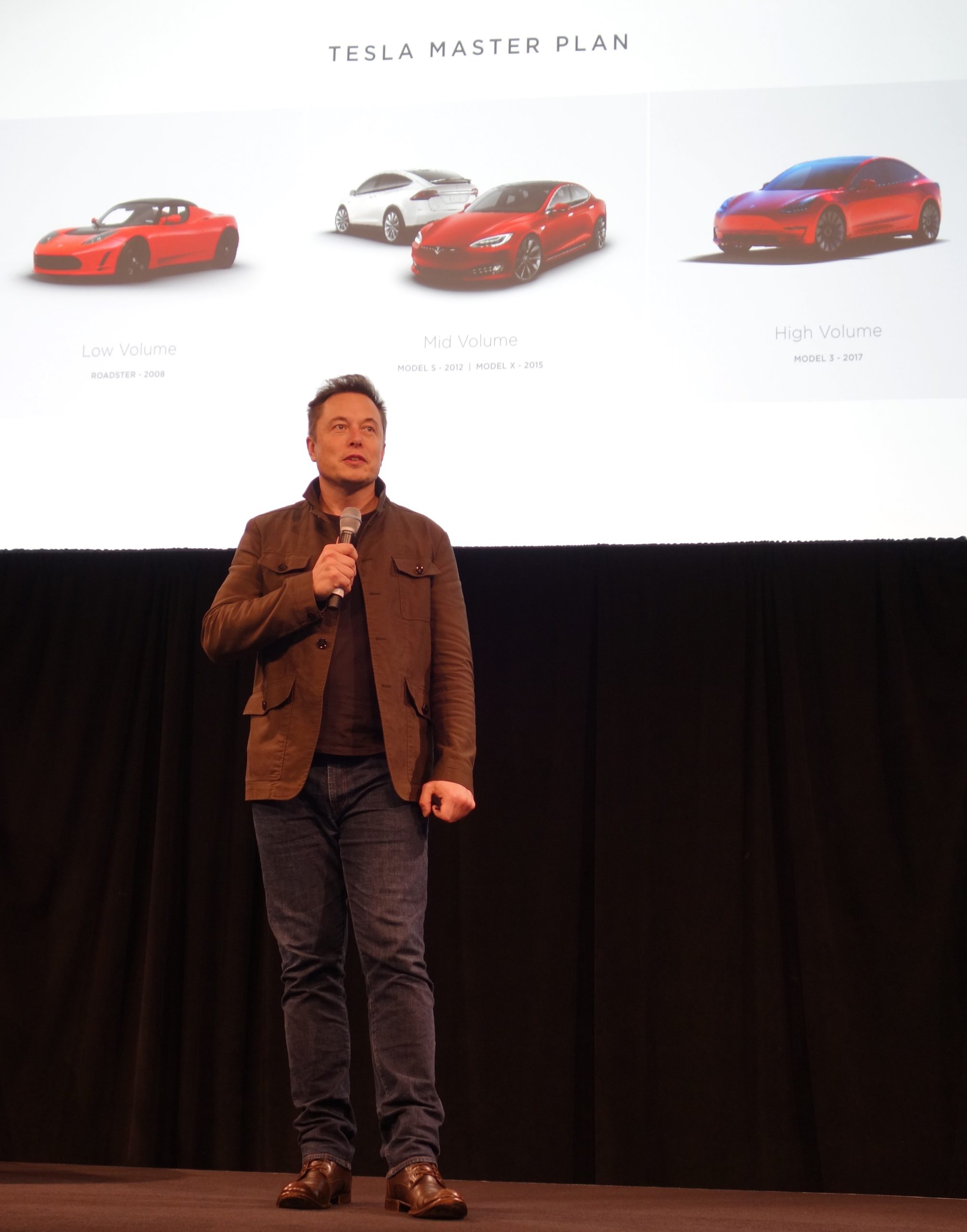

Tesla’s Market Share Growth

Perhaps best known to many consumers as a producer of electric vehicles (EVs), Tesla has beaten well-known legacy automotive companies like Ford and GM in the U.S. market to become the most profitable automaker in U.S. history despite the intense competition in the U.S. automotive sector. With a valuation of over $81 billion, Tesla is more than an automaker. Founded as Tesla Motors in 2003 in San Carlos, California, by Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning, today Tesla is a successful multinational company headquartered in Austin, Texas, that also specializes in renewable energy solutions, such as energy storage devices and solar panels, in addition to EVs. An early investor, Elon Musk became CEO in 2008. Tesla continuously innovates in many areas, especially in sustainable technology. This is evident not only in its products but also throughout its production, which includes the advanced use of robotics.

Despite its outstanding accomplishments, Tesla has encountered a number of external and internal challenges. Infrastructure has been slow to support long-distance EV travel, making traveling beyond a vehicle’s range a challenge due to a lack of readily available charging stations, especially in remote and rural areas. Some consumers express concerns over the capacity of the power grid to support the increase in EVs.

An industry characteristic of automakers is that they can face long-term reliability challenges—to greater and lesser degrees, of course. While automakers new to the industry may have a brief honeymoon period before long term reliability issues are evident, Tesla vehicles have now been on the market long enough for these issues to become evident.

Elon Musk is known for being outspoken about his views, especially through his social media posts mostly on X. The successor to Twitter, Inc., X is a wholly owned subsidiary of X Holdings Corp., which is mostly owned by Musk. In a display of his influence, on May 1, 2020, when he posted that Tesla’s stock price was too high, the company’s stock price immediately dropped.

Within the organization, persistent challenges have included employee dissatisfaction, loyalty issues, and retention problems. These internal problems, which frequently result from highly demanding work environments, high standards, and leadership concerns, have made it difficult to attract and retain a steady and loyal employee base and have impacted the company’s work culture.

Bibliography

Allsup, M. (2024, July 24). The quiet success of Tesla’s energy business. Latitude Media. https://www.latitudemedia.com/news/the-quiet-success-of-teslas-energy-business

Anderson, S., & Rosenston, M. (2024, March 27). The story behind Tesla’s success (TSLA). Investopdia. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/personal-finance/061915/story-behind-teslas-success.asp

Botsvadze, V. (2024, June 18). Tesla ranks no1 most valuable brand within automotive sector by brand value in 2024 thanks to Elon Musk’s personal brand. Medium. https://medium.com/@VladimerBotsvadze/tesla-ranks-1-most-valuable-brand-within-automotive-sector-by-brand-value-in-2024-thanks-to-elon-e95c62c6408b

Kolodny, L. (2024, June 21). Tesla internal data shows company has slashed at least 14% of workforce this year. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2024/06/21/tesla-has-downsized-by-at-least-14percent-this-year-internal-number-shows.html

Higgins, T. (2021). Power play: Tesla, Elon Musk, and the bet of the century. Doubleday.

Pulliam, S., & Ramsey, M. (2016, August 15). Elon Musk sets ambitious goals at Tesla – and often falls short. The Wall Street Journal.

1.1 Introduction

The problems mentioned in the example above about Tesla raise significant questions:

- Will relating and supporting industries, such as charging stations and power grid capacity, grow to meet the demand of EVs?

- To what degree will Tesla integrate with these industries to control them or partner with them to influence their growth?

- How will Tesla address the emergence of reliability issues in its vehicles?

- How will Elon Musk’s leadership style influence company success?

- How will Tesla address its talent attraction and loyalty concerns?

- Will Tesla be able to maintain its position as the leading electric vehicle manufacturer with the biggest market share in the United States?

- What emphasis will Tesla place on its EVs and other product lines, such as energy storage devices and solar panels, in the future?

- How will the company sustain its competitive advantage in the automotive industry and its success in renewable energy industries as the business expands?

As the market evolves and competition increases, the answers to these questions will depend on how well Tesla navigates its challenges, applies the right strategies, adapts to changing consumer preferences, and continues to innovate. These concerns, which are not unique to Tesla, are a few of the questions and issues addressed by strategic management.

1.2 Organization, Business, Company, Firm, Industry

Before we introduce strategic management, it is important to understand how the terms organization, business, company, firm, and industry are used in the book. Organization is the broadest term used to describe a specific entity and applies to entities in all sectors: private (for-profit), governmental (public), and not-for-profit (including nonprofit, nongovernmental organizations [NGOs], and voluntary organizations). Strategic management is important to all sectors. As a business textbook, the book focuses primarily on organizations in the private sector. A few examples of organizations in other sectors are given throughout the book, as you may work in the governmental and not-for-profit sectors at some stage in your career.

Organizations in the private sector are also referred to as businesses, companies, and firms. Therefore, all four terms can be correctly applied to entities in the private sector that engage in commerce and aim to make a profit. The terms organization, business, company, and firm are used interchangeably in the book.

Industry is a group of organizations, businesses, companies, or firms that offer similar products and services while competing in the marketplace for profit. The term industry is used to indicate this group of competing organizations, businesses, companies, or firms.

In the example of Tesla above, Tesla may be referred to as an organization, business, company, or firm. Tesla competes in at least two industries: the automotive industry and the renewable energy industry. Large multinational firms often compete in more than one industry.

Unlike businesses like Tesla, units in the governmental or public sector, such as departments in the federal government like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), are referred to as organizations. This also is true for not-for-profit organizations, like the Red Cross.

Organization is the broadest term used to describe a specific entity and applies to entities in all sectors: private (for-profit), governmental (public), and not-for-profit (including nonprofit, NGOs, and voluntary organizations). Organizations in the private sector are also referred to as businesses, companies, and firms. Therefore, all four terms can be correctly applied to entities in the private sector that engage in commerce and aim to make a profit. Industry is a group of organizations, businesses, companies, or firms that compete in the marketplace for profit.

1.3 Strategic Management Concepts and Theories & Analytical Frameworks and Tools

As a multidisciplinary field of study, strategic management incorporates concepts and theories from many disciplines. Concepts are ideas. Theories are collections of concepts that explain something. Common examples include the concept of gravity, which is an idea that is part of the theory of relativity; likewise, the concept of genetic mutation is a part of the theory of evolution. In business, theories are collections of concepts that explain something that occurs in the business world. For example, the concept of power is a part of leadership theories, such as shared leadership theory.

An analytical framework provides a structured format for analyzing data. Continuing with the example of the concept of power as an essential building block of leadership theories, there are multiple analytical frameworks that support analyzing power dynamics, such as French and Raven’s five bases of power—legitimate, reward, expert, referent, coercive power—that can be used to evaluate how leaders influence others.

Strategic management frameworks provide a structured format to analyze company data as it relates to a major area of strategic management. Strategic management analytical frameworks may also be referred to as strategic management tools.

Strategic management concepts and theories inform the analytical frameworks and tools used in strategic management. The terms frameworks and tools are used interchangeably in the textbook.

You learn many strategic management concepts and theories throughout the book, with frequent opportunities to apply multiple strategic management frameworks to analyze companies.

Application

- Think of additional examples of concepts, theories, and analytical frameworks. How many more examples can you identify?

Concepts are ideas. Theories are collections of concepts that explain something. An analytical framework provides a structured format for analyzing data. Strategic management frameworks provide a structured format to analyze company data as it relates to a major area of strategic management. Analytical frameworks for strategic management may also be referred to as strategic management tools.

1.4 What is Strategic Management?

Just as it is important to understand what strategic management is and how to apply its concepts and theories, analytical frameworks and tools are central to successful strategic management. The process of applying the concepts and theories through analytical frameworks and tools is known as case analysis. This chapter introduces you to the subject of strategic management; the next chapter teaches you how to apply the concepts, theories, and tools of strategic management through the process of conducting case analysis.

Strategic management is an area of business that is grounded in research. Like most areas of business, strategic management is both a focused area of business practice and a field of study supported by robust research. In this introductory chapter to strategic management, you first learn about strategic management in the context of business practice, and then you learn about strategic management as a field of study. The remainder of the book approaches strategic management as a research-grounded field of business practice.

Strategic management is a multidisciplinary subject, relying on and synthesizing all areas of business expertise, such as accounting and information systems, business information technology and cybersecurity, finance, insurance and business law, hospitality and tourism management, human resource management, business management, management consulting and analytics, entrepreneurship, innovation and technology management, marketing, and real estate. The primary aim of strategic management is to continuously apply evidenced-based analysis to formulating and implementing strategies that allow a firm to differentiate itself in the market. Strategic management uses many frameworks and tools that are based on many interrelated concepts and theories. To support you in learning these interrelated complex ideas and effectively applying them, we introduce you to the broad landscape of strategic management so that you can see the big picture of how the ideas fit together and then break them down in more detail so that you can apply them.

To understand the broad field of strategic management from both business practice and field of study perspectives, you need to understand the terms strategic leadership, strategic management, strategy, strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation. We introduce each of these below as a way for you to see the big picture of strategic management before addressing them in greater detail.

Strategic Leadership

Think about leadership and management. How are they similar? How are they different? One way to consider these different roles is that leaders define the direction the organization is going, while managers identify the roadmap for getting there. In practice, many employees both lead and manage, depending upon the size of a company and whether the management style of the firm is centralized or decentralized. When it comes to strategic management, both strategic leadership and strategic management are important.

Strategic leadership includes the responsibility, talent, capacity, power, and actions necessary to steer an organization strategically though a dynamic market to create and sustain a competitive advantage and to become and remain an industry leader. Strategic leaders direct the strategic management process.

Strategic leadership is an essential focus for top leaders in a company, such as those in the C-suite and the board of directors. Elon Musk, his colleagues in the C-suite, and Tesla’s board of directors provide strategic leadership for Tesla. However, strategic leadership is not always the exclusive focus of those at the very top of an organization, depending on whether a firm relies on a centralized or decentralized leadership style. In companies with a decentralized leadership style, leadership may be shared among more company leaders.

Strategic Management

Strategic management is the dynamic and ongoing process of managing a firm’s approach to strategy. Strategic management follows a structured process to methodically and thoroughly analyze the environment, industry, and firm as well as to formulate and implement strategy.

Large companies often have departments or teams focused exclusively on leading strategic management. Managers in a firm also participate in strategic management. To support their data driven decisions, managers solicit data from areas of business expertise such as accounting and information systems, business information technology and cybersecurity, finance, insurance and business law, human resource management, and marketing.

You will likely be asked for data that supports strategic management early in your career. Demonstrating that you understand how this data can support broader strategic management efforts can accelerate your career. Below, we explore exactly how competency in strategic management is a vital skill to all business majors in all career settings and at all career stages, an assertion that will be explained in greater detail later in the book.

Strategy

Think about the strategies you use to be successful in your coursework. They may include studying, time management, and remaining up to date on assignments.

Strategic management focuses on strategy. Strategy is a collection of organizational plans and processes that focus on creating and sustaining superior firm performance relative to a company’s competitors, which creates a sustainable competitive advantage. Strategies are broad and long range, with few specifics. They do not typically address actions.

The strategies this book covers in detail include corporate-level strategy, business-level strategy, innovation strategy, sustainability and ethics strategy, technology strategy, and multinational strategy. We introduce those in section 1.5 and cover them in detail in their own dedicated chapters.

Strategic Analysis

In firms, strategic analysis is the process of applying strategic management concepts and theories with analytical frameworks and tools to conduct a thorough 360-degree analysis of a firm. This enables strategy managers to make evidenced-based decisions about strategy formulation and strategy implementation in all areas of the company’s operations.

You conduct strategic analysis of a company by conducting a case analysis, which the next chapter describes in detail so that you may apply the knowledge throughout the remainder of the book.

When you graduate, you likely will be involved in strategic analysis either immediately or very early in your career, depending on the size company you join and its management style, whether you serve as an internal or external consultant or you begin an entrepreneurial venture of your own. Competency in strategic analysis is essential to both navigating a career and to starting your own business.

Strategy Formulation

Strategy formulation is the process of designing strategies throughout all levels and areas of an organization. Successful strategy formulation relies on evidenced-based decisions that are grounded in strategic analysis.

Strategic leaders and managers in firms formulate strategy. You analyze the company strategies when you conduct a case analysis. As with strategic analysis, you learn exactly how understanding strategy formulation is important for your career as you progress though the book.

Strategy Implementation

Strategy implementation is the process of executing the strategies that a company has formulated.

Employees at all levels of a firm are responsible for implementing the company’s strategies. You will be involved in strategy implementation immediately in your career. Knowing how strategy is analyzed and formulated gives you an advantage in implementing strategy.

Application

- Think of the jobs you have had.

- Were there people that engaged exclusively in leadership and people that engaged exclusively in management, or did the same person both lead and manage?

- Describe the responsibilities leaders had.

- Discuss the tasks managers did.

- What do you see as the primary differences in leadership and management from your experience?

- Can you identify a specific strategy that the company was implementing? Why do you think it was or was not visible to you?

Strategic management is both a focused area of business practice and a field of study supported by robust research. Strategic leadership includes the responsibility, talent, capacity, power, and actions necessary to steer an organization strategically though a dynamic market to create and sustain a competitive advantage and to become and remain an industry leader. As a focused area of business practice, strategic management is the dynamic and ongoing process of managing a firm’s approach to strategy. Strategic management follows a structured process to methodically and thoroughly analyze the environment, industry, and firm as well as to formulate and implement strategy. Strategy is a collection of organizational plans and processes that focus on creating and sustaining superior firm performance relative to a company’s competitors, which creates a sustainable competitive advantage. Strategy formulation is the process of relying on evidence-based decisions that are grounded in strategic analysis to design strategies throughout all levels and areas of an organization. Strategy implementation is the process of executing the strategies that a company has formulated.

Bibliography

Carpenter, M. A., & Sanders, W. G. (2009). Strategic management. Pearson/Prentice-Hall.

Porter, M. E. (1996, November–December). What is strategy? Harvard Business Review, 74(6), 61–79.

Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. Free Press.

Block, S. R., & Miller-Stevens, K. (2021). Power and control. In Founders and organizational development (1st ed., pp. 27–50). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003057628-2-2

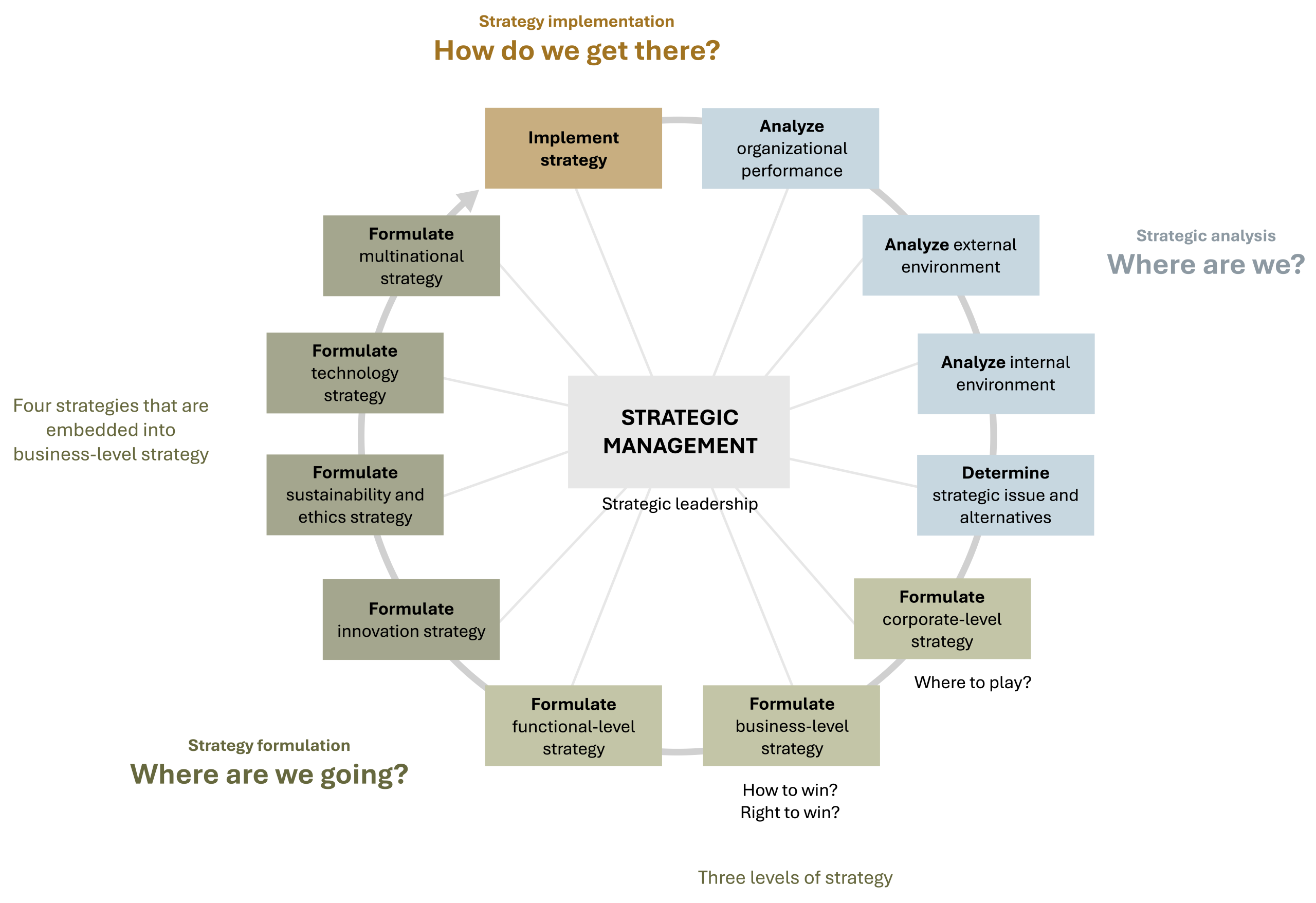

1.5 The Analysis, Formulation, Implementation (AFI) Framework

The practice and research of strategic management includes the three pillars of strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation. These are represented in the analysis, formulation, implementation (AFI) framework that guides the focus and structure of this book.

Figure 1.3 shows the AFI framework. We cover each element below.

At the center of the AFI framework are strategic management and strategic leadership, with which you are now familiar.

Below you learn more about the three stages of the strategic management process—strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation—and the three essential questions that guide each stage. Next you learn what you’re specifically analyzing in the strategic analysis stage and in what order. Then the chapter focuses on strategy formulation, which is addressed at three organizational levels of strategy (corporate-level strategy, business-level strategy, and functional-level strategy) and by the more focused strategies that are embedded into business-level strategy (innovation strategy, sustainability and ethics strategy, technology strategy, and multinational strategy). Finally, you consider strategy implementation.

Strategic management’s foundations rest in three essential questions that align with the three stages of strategic management:

- Where are we?

- Where are we going?

- How are we going to get there?

Strategic analysis addresses “Where are we?” Strategy formulation begins to answer, “Where are we going?” And strategy implementation addresses “How are we going to get there?”

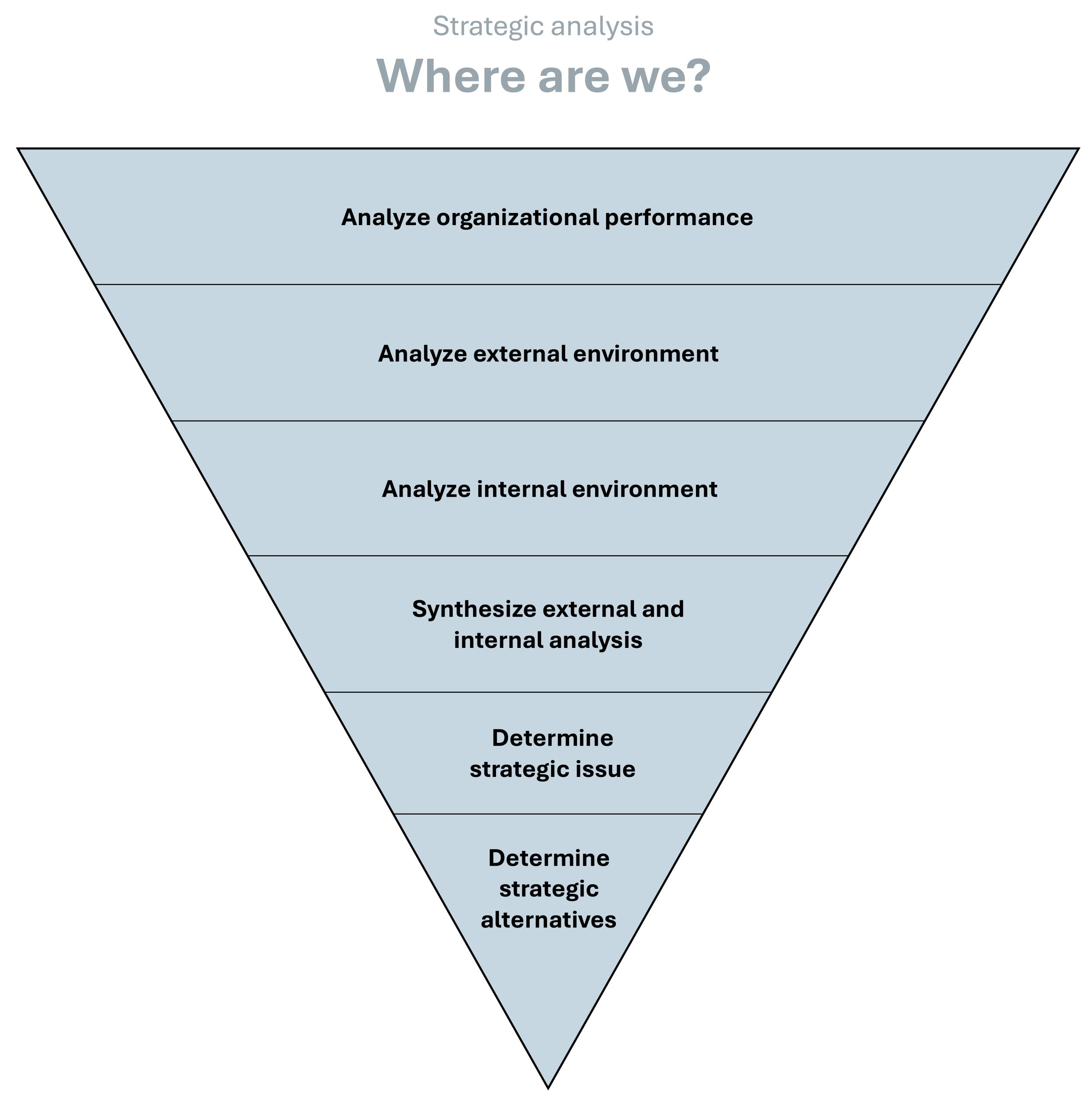

Strategic Analysis

Strategic analysis addresses the broad question “Where are we?” and includes multiple steps. In this section, we review the steps to strategic analysis so that you can see the overall approach to strategic analysis. Later chapters discuss what is involved in each step of strategic analysis. You learn how to conduct a strategic analysis when you conduct a case analysis using strategic management tools.

The order of the steps is important. First, analyze organizational performance, which assesses the robustness and congruence of a firm’s mission, purpose, vision, values, and goals as well as its financial position, its market position, and other relevant quantitative data. This step also includes a review of the firm’s balanced scorecard. Next, review the external environment of the firm, which considers the company’s general, industry, and competitive environments. Then analyze the internal environment of the firm, which assesses a firm’s resources, capabilities, core competencies, and value chain. Once you have analyzed an organization’s organizational performance and its external and internal environments, synthesize the analysis using a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis. Finally, identify a strategic issue and strategic alternatives.

Each of these steps in strategic analysis is the subject of a chapter, ensuring that you learn them in much greater detail as you make your way through the book.

Consider figure 1.4. The order of the steps in strategic analysis is important, as each step progressively narrows the focus until you can define a strategic issue and how to address it.

A firm’s strategic issue and strategic alternatives are central to strategic management. They are introduced here and elaborated upon in detail in subsequent chapters.

A firm’s strategic issue is the most important, urgent, broad, long-term matter that the company is facing. Strategic issues are the result of multiple causes in multiples areas of a business and require significant organizational talent and resources to resolve. Addressing a strategic issue moves a firm toward its mission, purpose, and vision, and it should therefore be congruent with the firm’s values and goals. A strategic issue focuses on the present and specific organizational context, addressing what is happening with this firm at this time, in this place, and under these circumstances. What a strategic issue is and how to determine it is elaborated on in subsequent chapters.

A strategic alternative is an action that addresses and has the potential to resolve every aspect of a strategic issue. Strategic alternatives are also explained in greater detail in later chapters.

Strategy Formulation

Once strategic analysis is complete, strategy formulation begins. This process addresses the broad question “Where are we going?” Strategy formulation is presented in order from broadest to narrowest (in relation to the level of the organization where it is addressed).

Figure 1.5 illustrates strategy formulation, and the text below explains each element in the figure.

There are three levels of strategy in an organization: corporate-level strategy, business-level strategy, and functional-level strategy. Strategy is formulated at all levels of a company.

Corporate-Level Strategy

The corporate level of a company consists of senior executives in the C-suite, and if the company is large enough, it includes the board of directors. Corporate-level strategy is a companywide strategy that focuses on creating and maintaining a firm’s competitive advantage by creating synergy within and between multiple industries, markets, market segments, and businesses, across multiple industry value chains, and in different geographical locations. Corporate-level strategy is the responsibility of senior executives and the board of directors.

When you conduct a case analysis, you may analyze a company’s corporate-level strategy.

Business-Level Strategy

Business-level strategy focuses on how to compete within an organization’s chosen market and market segments to create and sustain competitive advantage. Business-level strategy addresses a firm’s strategic market position (cost leadership and differentiation) and strategic market size (whether it competes in a focused market segment or a broad market).

Business-level strategy is the strategy of a strategic business unit. A strategic business unit is a fully functional unit of a business that has its own vision and direction and may be part of a larger organizational unit like a division. The unit’s focus and structure may be based on factors such as markets served, products offered, or regions served. Smaller firms may have only one strategic business unit, and large corporations may have more than one strategic business unit.

Strategic business units focus on one business-level strategy. Smaller firms that have only one strategic business unit have only one business-level strategy. In large companies with more than one strategic business unit, different strategic business units may have different business-level strategies. Therefore, large corporations that have more than one strategic business unit potentially have multiple business-level strategies.

All strategy should be specific and differentiating. Though business-level strategies include a finite number of strategies that are common to all companies, companies implement them in ways that reflect their specific company conditions.

In addition to each strategic business unit’s business-level strategy, there are additional strategies that are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level. The four embedded strategies that are covered in this text are innovation, sustainability and ethics, technology, and multinational strategy.

When you conduct a case analysis, you may analyze a company’s business-level strategy and its innovation, sustainability and ethics, technology, and multinational strategies.

Innovation Strategy

All companies of all sizes and stages of development and growth must address innovation and formulate innovation strategies. Innovation strategies are strategies that are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level that focus on a firm’s approach to innovation so that it can create and sustain a competitive advantage.

Sustainability and Ethics Strategy

Sustainability strategies are strategies that are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level that focus on a company’s approach to reducing its adverse environmental and social impacts while establishing competitive differentiation through the firm’s positive environment and social performance (usually measured against environmental, social, and governance [ESG] metrics).

Business ethics strategies are strategies that are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level that focus on a company’s approach to increasing ethical behavior and remaining legally compliant.

Technology Strategy

Technology strategies are strategies that are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level that focus on a company’s approach to using technology as a source of competitive differentiation and that align the firm’s use of new and emerging technologies with the firm’s roadmap to reach its vision and overall business objectives.

Multinational Strategy

Multinational corporations (MNCs) are firms that have operations in more than one country.

Though all successful companies formulate innovation, sustainability and ethics, and technology strategies, not all businesses are MNCs and therefore not all companies formulate multinational strategies. Multinational corporations formulate multinational strategies, which are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level, and are strategies that address different ways to position the company in multinational markets. They include international, multidomestic, global, and transnational strategies.

Three Critical Strategic Questions

Strategy can be described as a firm’s answer to three strategic questions that are critical for every organization:

- Where to play?

- How to win?

- Right to win?

The first two questions (“Where to play?” and “How to win?”) are addressed at the two broad levels of strategy. “Where to play?” is answered at the corporate level with corporate-level strategy. “How to win?” is addressed through business-level strategy at the strategic business unit level. The third question (“Right to win?”) is addressed by the specific strategies that are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level: innovation strategy, sustainability and ethics strategy, technology strategy, and multinational strategy. All three questions drive the firm’s formulation of a roadmap and action plan toward sustained superior performance.

Where to play?

This first question is addressed at the corporate level of a company and considers which industries, markets, market segments, businesses, and regions in which the firm wants to operate (play). The answers to the question are largely determined by the firm’s assessment of the attractiveness and profit potential of alternative markets, market segments, businesses, and synergies between them. The answers also provide important solutions to the allocation of limited company resources to different businesses. In this sense, it is also important for every organization to decide where not to play. Overall, the strategy that focuses on where to “play” can be described as the firm’s search for markets and market segments that are attractive today and in the future.

How to win?

After the first question has been addressed, the firm needs to decide how it will win in its chosen markets, and this is approached through business-level strategy at the strategic business unit level of a company. Answers to this question are largely determined by the firm’s ability to develop a winning strategy around its resources, capabilities, and core competencies that are superior to those of its competitors and that will create value for the firm’s customers. There are various drivers of how a firm can win in its chosen markets, like differentiation and cost leadership or whether the firm chooses to operate in a focused or broad market. Overall, the “How to win?” question addresses the firm’s search for a sustainable competitive advantage.

Right to win?

Once the question of where to play has been resolved at the strategic business unit level through business-level strategy, the question “Right to win?” can be considered. All companies have the ambition to win in their chosen markets. They want to gain market share, increase revenue and profit, and enter new markets and regions. However, strategy is more than a wish list of what a company would ideally want to do and achieve. Strategy is a company-specific roadmap for navigating its industry, directing how a firm moves from its current state toward the firm’s vision.

With this conception of strategy in mind, the company’s right to win is addressed by the specific strategies that are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level: innovation strategy, sustainability and ethics strategy, technology strategy, and multinational strategy. An organization needs a clear right to win in its chosen markets. This right is supported by truly differentiating and valuable resources, capabilities, and core competencies that are unique for the specific organization.

Let’s take the example of your university’s volleyball team. The team surely has the ambition to do well, win as many games as possible, and maybe even win the conference title. Going beyond just the hope to win requires a clear right to win. This right (or reason or justification) to win could be that the team has the best coach, the best training conditions, the best infrastructure, the best team captain, or outstanding individual players. Maybe it is not the superior quality of individual players but the superior chemistry and teamwork that makes the team win. Whatever it may be, without a true right to win, strategy just becomes wishful thinking— an exercise written on paper.

On a business level, the right to win needs to be clearly anchored in business-level strategy because it is in strategic business units where a firm decides how it wants to win in its chosen markets.

Functional-Level Strategy

The third level of strategy formulation is functional-level strategy. Functional-level strategy, or just functional strategy, focuses on implementing strategy in business support units. Business support units focus on single business functions, such as accounting, business information technology, business law, finance, human resource management, marketing and sales, supply chain management, operations, and procurement.

Many of you will join firms in business support units in your first professional positions after graduation. All types of strategy cascade down to business support units, influencing strategy implementation at each level. Because functional-level strategy is the focus of most courses in your major, it is not addressed in detail in this book.

Strategy Implementation

Once strategy formulation is complete, each type of strategy must be implemented. Strategy implementation addresses the question “How are we going to get there?” Unless it is concerning a new strategy area for a company, then strategy implementation often begins with analyzing the gap between the previous strategy and the newly formulated strategy. Strategy implementation involves setting goals, allocating resources to operationalize the strategy, communicating and cascading the strategy, ensuring the organizational design and control systems support the strategy, hardwiring the strategy throughout the organization, aligning culture to support the strategy, and managing the changes required to implement the strategy. Strategy implementation is the subject of Chapter 13.

Application

- Think about your career aspirations. Maybe you would like to join a large firm as a subject expert in an area such as accounting or marketing. Perhaps you plan to start an entrepreneurial venture (or already have) or maybe you want to work as a consultant. Now think about your career from the point of view of the AFI framework and the roles of strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation.

- What analysis are you conducting to support your strategy? Are you analyzing your strengths and preferences? Perhaps you are considering the job market and projected income growth over five years. What else is important to you?

- Based on your analyses, what strategy have you formulated to ensure are you are successful? State your strategy in one concise sentence.

- Have you begun implementing your strategy? What else do you need to do before implementing your strategy?

The analysis, formulation, implementation (AFI) framework represents the stages of the strategic management process: strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation. Strategic analysis addresses the question “Where are we?” Strategy formulation begins to answer “Where are we going?” Strategy implementation addresses the question “How are we going to get there?” Strategy formulation includes three levels of strategy in an organization: corporate-level strategy, business-level strategy, and functional-level strategy. This text discusses four specific strategies that are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level: innovation, sustainability and ethics, technology, and multinational strategy. Strategy addresses three critical strategic questions that every organization has to answer. “Where to play?” is addressed through corporate-level strategy. “How to win?” is addressed through business-level strategy in a strategic business unit. “Right to win?” is addressed through the four specific strategies that are embedded into business-level strategies at the strategic business unit level. Strategy implementation is executing strategy at all levels across a firm.

Bibliography

Finkelstein, S., Hambrick, D. C., & Canella, A. A. (2008). Strategic leadership: Theory and research on executives, top management teams, and boards. Oxford University Press.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. Free Press.

Ungerer, M., Ungerer, G., & Herholdt, J. (2016). Navigating strategic possibilities: Strategy formulation and execution practices to flourish (1st ed.). KR Publishing.

1.6 Intended, Deliberate, Emergent, Realized, and Unrealized Strategies

The AFI framework is a popular and useful model of strategic management. It is a top-down, rational model that is driven by managers focused on managing the strategic management process and by strategic leaders steering a firm strategically. It is planned and methodical.

There are other approaches to strategy, such as Mintzberg and Waters’s (1985) model that considers intended, deliberate, emergent, realized, and unrealized strategies. This view considers how strategies evolve over time.

The AFI framework and Mintzberg and Waters’s approach are two schools of strategic thought that business leaders often find complementary.

Intended Strategy

An intended strategy is the strategy that an organization plans to implement. The structured strategic management process described above produces intended strategies.

Deliberate Strategy

Many things can happen between planning a strategy and implementing it, potentially requiring changes to the intended strategy. A deliberate strategy is the strategy that a firm implements in such a situation. It is a planned response to alter, but not completely change, an intended strategy in the face of dynamic conditions. Sometimes the factors that lead to the difference between an intended and deliberate strategy are internal to the organization, such as talent and managerial capacity. Often these differences can come from sources external to the organization, like the COVID-19 global pandemic, climate change, and changing competition.

Emergent Strategy

An emergent strategy is a completely new and unplanned strategy that is formulated in response to an unexpected circumstance, which most often originates from a firm’s external environment (such as the emergence of a new technology). Emergent strategies are as important to a firm’s success as intended and deliberate strategies. Firms that are skilled at horizon scanning for new opportunities and are nimble in response to changing conditions are better positioned to take advantage of these dynamic conditions and formulate effective and profitable emergent strategies.

Companies formulate emergent strategies and deliberate strategies in response to changing circumstances. The distinction is that deliberate strategies alter, but do not completely change, the intended strategy. They tend to be dynamic tweaks to the intended strategy. Emergent strategies, on the other hand, are completely new strategies that are formulated in response to surprising and unforeseen conditions. An emergent strategy is completely different than the intended strategy and requires a change of strategic direction.

Realized Strategy

A realized strategy is the strategy that an organization follows over time. Realized strategies include a firm’s intended strategy and deliberate strategy if the company has altered but not completely changed the intended strategy in the face of dynamic conditions. Realized strategies may also include an emergent strategy if an unanticipated and completely new opportunity has arisen and the firm has been nimble and quick enough to capitalized on it by formulating an emergent strategy.

One way to think about intended, deliberate, and realized strategies is as an evolution of strategy over time. The company initially plans an intended strategy. A deliberate strategy is the part of the intended strategy a firm implements after taking into account dynamic conditions either in the company’s external environment, such as a new competitor, or in the firms’ internal environment, like a change in CEO. The deliberate strategy alters, but does not completely change, the intended strategy. A firm’s realized strategy is the strategy that an organization follows over time that includes the intended and deliberate strategies and also incorporates any emergent strategies that have been formulated in response to conditions that were unforeseen when the intended and deliberate strategies were formulated. A firm’s realized strategy can be different than the intended and deliberate strategy if the company has formulated an emergent strategy.

The Southern Bloomer manufacturing company is an example that illustrates intended, deliberate, emergent, and realized strategy. Managers of prison facilities believed that the underwear brands currently on the market were not suitable for harsh prison activities and constant laundry processes. Southern Bloomer saw this need and responded. They planned well and made an intended strategy to meet this market demand. This involved a structured approach to analyzing factors external to the company, such as a market assessment and competition analysis, as well as an evaluation of factors in their internal firm environment, such as talent and managerial capacity.

Southern Bloomer started selling underwear made from mostly cotton fabric to cope with prison activities and the institutional environment. They responded to customer feedback and market conditions and grew their business to a solid customer base within that market, eventually supplying institutional underwear to 125 prisons. This was Southern Bloomer’s deliberate strategy because it was closely aligned to their intended strategy and amended to respond to external and internal factors.

An emergent strategy arose from an unexpected challenge related to the excess scrap fabric produced during production. The company had been discarding the leftover fabric. One day, cofounder Don Sonner visited a gun shop with his son, where he spotted a potential use for his scrap fabric. The patches that the gun shop sold to clean the inside of gun barrels were of poor quality. According to Sonner, when he saw those flimsy woven patches that unraveled when touched, he thought, “That’s what I can do with the scrap fabric!” Unlike other gun-cleaning patches, the patches made by Southern Bloomer didn’t shed threads or lint, which can hurt a gun’s accuracy and reliability. Patches produced by Southern Bloomer quickly became popular with the military, police departments, and gun enthusiasts. Soon, Southern Bloomer was selling thousands of pounds of patches each month. A simple trip to a gun store unexpectedly led to a profitable new strategy (Wells, 2002).

In summary, the intended strategy of Southern Bloomer was to produce durable underwear for institutional settings like prisons. The company pursued this strategy closely and executed a deliberate strategy based on this intended strategy, amended to respond to dynamic conditions both in its external and internal environments. This strategy was successful and profitable, and the company continued to pursue this strategy. An emergent strategy arose that allowed Southern Bloomer to use the scrap fabric it had been sending to landfills. Southern Bloomer was quick to spot this new opportunity and nimble enough to capitalize on it. They seized the opportunity to produce gun-cleaning patches from their scrap material left over from their manufacturing of prison underwear, turning that into a second profitable line of business. Rather than sending this scrap fabric to landfills, the company found a new alternative way to make use of the material. They turned a challenge into an opportunity. Southern Bloomer’s realized strategy was formed from a combination of its intended strategy, deliberate strategy, and emergent strategy. They continued to manufacture and sell underwear to prisons and opened a new successful business line in a new market to sell patches to clean guns to a variety of customers.

Unrealized Strategy

An unrealized strategy is an abandoned part of the intended strategy. There are many reasons why parts of strategies are abandoned, creating a gap between strategy formulation and implementation. These are elaborated on in detail in Chapter 13.

Let’s now consider all the strategies with another example. David McConnell was an aspiring author who faced difficulty selling his books. He tried several strategies and conventional marketing methods before he discovered the idea of giving out free perfume to those who bought his books. This innovative approach not only attracted attention but also helped him find success, leading him to lay the foundation of what would become the California Perfume Company, which was formed to market perfumes. This company developed into the massive personal care goods company that is now known as Avon. Though McConnell’s dream of becoming a successful writer remained an unfulfilled plan, he created a successful strategy through Avon that was mostly driven by his capacity to seize the moment by adjusting to changing circumstances and making use of newly emerging tactics. Ultimately, his journey transformed a setback into a remarkable opportunity.

Let’s look at Avon’s story through the lens of intended, deliberate, emergent, realized, and unrealized strategies. David McConnell had an intended strategy to sell books he had written. He executed this intended strategy with little initial success. His books were not selling well, and his business was not profitable. In the face of this market information, McConnell decided to offer perfume as an incentive to buy his books. This was his deliberate strategy because he amended his original intended strategy of selling books to take into account lagging sales by adding the gift of perfume. His deliberate strategy altered but did not completely change his intended strategy. His focus was primarily on selling books and adding the gift of perfume was an innovation that tweaked his intended strategy. When the perfume sales proved to be a hit with customers, this provided a market opportunity that McConnell had not anticipated. The emergence of a market for the perfume independent of the books was new and unanticipated. McConnell acted quickly and decisively to take advantage of this new and unforeseen market opportunity and formulated a new emergent strategy of selling only perfume. The emergent strategy of selling only perfume was completely different than his original planned intended strategy of selling books and significantly different than his deliberate strategy of adding perfume as a gift to incentivize customers to buy his books. He capitalized on this emergent strategy that came from his own innovation. The strategy he followed over time, his realized strategy, is selling perfume. He discarded his original intended strategy of selling books and this became an unrealized strategy in the end because he abandoned that all together.

Application

- In section 1.5, you considered your career aspirations form the point of view of strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation. Now think about your career through the lens of Mintzberg and Waters’s model.

- What is your intended career strategy?

- Have you yet responded to any emergent strategies in your career plans?

- How will horizon scanning help you prepare for emergent opportunities?

An intended strategy is the strategy that an organization plans to implement. The structured strategic management process described above produces intended strategies. A deliberate strategy is a planned response to alter, but not completely change, an intended strategy in the face of dynamic conditions. An emergent strategy is a completely new and unplanned strategy that is formulated in response to an unexpected circumstance. A realized strategy is the strategy that an organization follows over time. Realized strategies include a firm’s intended strategy and deliberate strategy if the company has altered but not completely changed the intended strategy in the face of dynamic conditions. Realized strategies may also include an emergent strategy if an unanticipated and completely new opportunity has arisen and the firm has been nimble and quick enough to capitalized on it by formulating an emergent strategy. An unrealized strategy is an abandoned part of the intended strategy.

Bibliography

Avon. (n.d.). We believe in the beauty of doing good. Avon. https://www.avonworldwide.com/about-us/our-values/policies-positions/equity-inclusion

Chari, S. (2015). Market environment as a source of information: The effects of uncertainty on intended and realized marketing strategy. In M. Dato-on (ed.), The sustainable global marketplace. Developments in marketing science: Proceedings of the academy of marketing science. Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-10873-5_185

Mintzberg, H. (1978). Patterns in strategy formulation. Management Science, 24, 934–949.

Mintzberg, H., & Waters, J. A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6(3), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250060306

Mintzberg, H. (1993). The rise and fall of strategic planning: Reconceiving roles for planning, plan, and planners. Simon & Schuster.

Mintzberg, H. (1994, January–February). The fall and rise of strategic planning. Harvard Business Review, 72, 107–114.

Wells, K. (2002). Floating off the page: The best stories from the Wall Street Journal’s middle column. Simon & Schuster. pg 97.

1.7 Why Strategic Management Is Important

As you have learned, strategic management is a dynamic and ongoing process consisting of strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation. Strategic management is a critical business activity.

Strategy addresses the fundamental business question of how to create and sustain a competitive advantage by positioning a firm for superior performance relative to its competitors. This is a question all firms must ask throughout each step of the strategic management process.

Strategic leaders are responsible for ensuring their company has the human talent and organizational capacity to carry out robust and dynamic strategic management. They have the power to direct actions to ensure a sound, evidence-based strategy is formulated and implemented throughout all levels of the firm and in all areas of strategy. Strategic leadership is essential to successful strategic management.

Strategic management and strategic leadership are central to whether a company survives, grows, is successful, adapts to changing conditions, and becomes a market leader. Business success rests on strategy and its successful management and leadership.

Strategic management and strategic leadership are central to whether a company survives, grows, is successful, adapts to changing conditions, and becomes a market leader. Business success rests on strategy and its successful management and leadership.

Bibliography

Porter, M. E. (1996, November–December). What is strategy? Harvard Business Review, 74(6), 61–79.

1.8 The History of Strategic Management

When studying any field of study, it is important to understand its history and the pivotal events that shaped it. Strategy is a part of human history. Prior to written histories, indigenous nations employed strategy to form complex alliances. For example, before European contact in the Americas, many indigenous nations formed elaborate federations and complex trade agreements (Blackhawk, 2023).

Strategy appears in historical, religious, and literary texts:

- Published in the late spring and autumn period, which corresponds to approximately the fifth century BC, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War is an ancient Chinese treatise on military strategy that has influenced both Eastern and Western military strategy. Among its advice, is “to win without fighting is the best.”

- In the Latin poem the Aeneid (written between 29 and 19 BC), Virgil recounts the story of the Trojan Horse. After an unsuccessful ten-year siege of Troy, the Greeks build a large wooden horse that hides a military force; they station it outside Troy and then pretend to sail away. Intrigued, the Trojans roll the wooden horse into their city and unknowingly roll their enemy inside along with it.

- The Prince is a political treatise written by Florentine Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (1469–1527). It contains the famous maxim “the ends justify the means.”

Military strategy is also studied across all nations. A few examples include Napoleon’s military defeat at Waterloo in 1851, which illustrates how spreading resources too thinly can lead to defeat. In the American Civil War (1861–1865), although the Confederacy is credited with having better generals, the Union won. This is assessed to be due in part because the Union possessed better resources and employed them more successfully. Many battles of World War II (1939–1945) are still studied today. Among them is the D-Day invasion that aimed to liberate Europe from Nazi control. This is credited as bringing together many important factors for strategic success, including excellent intelligence, superior planning, and detailed preparation.

Strategic management as a field of study emerged over the last century, with several pivotal events focusing its formation.

- In 1911, Frederick W. Taylor publishedThe Principles of Scientific Management, which advocated “one best way” of performing important tasks. Although the merits of “one best way,” are largely disputed today, Taylor’s emphasis on maximizing organizational performance became the core focus of strategic management as the field developed.

- Building on ideas about efficiency from Taylor and others, Henry Ford pioneered assembly lines for creating automobiles. Lowering costs dramatically allowed a once luxury item to become much more affordable.

- In 1959, the Ford Foundation widely circulated a report that recommended all business schools offer a capstone course to integrate knowledge across different business fields. The aim was to teach students to address complex business problems by emphasizing critical thinking skills. This propelled strategic management to the foreground of business education.

- In 1962, Sam Walton opened the first Walmart in Rogers, Arkansas. A decade later, Walmart was the largest company in the world. Strategic management needed to adapt to address companies like Walmart.

- In 1980, the Strategic Management Journal was created, which facilitates research and focuses a community of scholars.

- Also in 1980, Harvard professor Michael Porter published Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. Porter is a significant thought leader in strategic management.

- In 1995, Jeff Bezos launched Amazon, changing the landscape of shopping to online. Strategic management needed to adapt to address the rise of companies like Amazon.

- In the early 2000s, a series of companies such as the Enron Corporation, WorldCom, Tyco, Qwest, and Global Crossing brought ethics to the foreground of business as executives were imprisoned, investors lost money, and jobs were lost.

- In 2005 Thomas L. Friedman published The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century, which argues that firms in developed countries are losing the advantage they had taken for granted. One implication is that these firms will need to improve their strategies if they are to remain successful. This brought the implications of multinational competition to the foreground for strategic management.

- Although the causes of climate change have been present since nineteenth century, it was not until 1938 that amateur scientist Guy Callendar collected records from 147 weather stations across the world, and doing all his calculations by hand, discovered that global temperatures had risen 0.3°C over the previous fifty years. He argued that carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from industry were responsible for global warming. In 1967, researchers Syukuro Manabe and Richard Wetherald produced the first accurate computer model of Earth’s climate. However, it was not until 2006, when former U.S. Vice President Al Gore published An inconvenient Truth, that climate change became a household phrase in the U.S. Climate change is a major force behind the rise of sustainability as an essential business focus. Strategic management needed to adjust to this change.

- In 2018, Apple became the first company to be worth $1 trillion.

- Leading technology company NVIDIA is well-known for its graphics processing units (GPUs). Today, NVIDIA continues to innovate through technology, integrating deep learning, artificial intelligence (AI), and gaming. Through its advancements in AI and gaming, the corporation has been important in bringing technology to the center of social media. As one of the biggest firms by market capitalization, NVIDIA has sometimes out-performed Apple throughout the years, showing its growing significance in the technology sector, particularly with the rise of AI-driven technologies. Strategic management needed to adapt to address companies like Apple and NVIDIA. It also needed to integrate the megatrend of technology as a primary focus.

When studying any field of study, it is important to understand its history and the pivotal events that shaped it. Strategy is a part of human history. Prior to written histories, indigenous nations employed strategy to form complex alliances. Strategy appears in historical, religious, and literary texts. Strategic management as a field of study has evolved and matured over the last century.

Bibliography

Blackhawk, N. (2023). The rediscovery of America, native peoples and the unmaking of U.S. history. Yale University Press.

Bracker, J. (1980). The historical development of the strategic management concept. Academy of Management Review, 5(2), 219–224.

Freedman, L. (2013). Strategy: A history. Oxford University Press.

Gore, A. (2007). An inconvenient truth. Penguin.

Taylor, F. W. (2012). The principles of scientific management. (1st ed.). The Floating Press.

Friedman, T. L. (2005). The world is flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century (1st ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. Free Press. (Republished with a new introduction, 1998.)

NVIDA. (n.d.). World leader in artificial intelligence computing NVIDIA. NVIDA. https://www.nvidia.com/en-us.

1.9 Contemporary Critique of Strategic Management

In addition to understanding a field of study’s history, it is also valuable to understand its criticisms. Strategic management is a dynamic and evolving field of practice. Along with the pivotal events presented in section 1.8, criticism of strategic management influences the direction in which the field continues to grow.

Criticism about strategic management as a field of study captures the ways in which scholars and business leaders think critically about the subject and process of managing strategy. Since strategic management is a field that requires critical thinking, scholars and business leaders embrace criticism as an opportunity to thoughtfully consider it and respond so that the field continuously improves.

Strategic management is a resource-intensive process. Some strategic leaders are concerned about the time and cost to focus on a thorough strategic management process. Firm executives can be skeptical whether strategic management achieves its intended outcome of formulating and implementing evidence-based strategies that are grounded in analysis. A few critics of strategic management suggest that it constrains firms from adapting rapidly to changing circumstances.

To be open to criticism is not to suggest that the value of strategic management is under question. The value of strategic management is well established. To be open to criticism reflects a confidence in the value of strategic management and a commitment to continuously improving it. Continuous assessment and improvement is not only central to strategic management; it is a primary focus of all areas of business practice and functional expertise, including accounting and information systems, business information technology and cybersecurity, finance, insurance and business law, hospitality and tourism management, human resource management, business management, management consulting and analytics, entrepreneurship, innovation and technology management, marketing, and real estate.

Strategic management is a dynamic and evolving field of practice. Criticism of strategic management influences the direction in which the field continues to grow.

Bibliography

Brown, S. L., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (1998). Competing on the edge: Strategy as structured chaos. Harvard Business School Press.

Burgelman, R. A., & Grove, A. S. (2007). Let chaos reign, then reign in chaos-repeatedly: Managing strategic dynamics for corporate longevity. Strategic Management Journal, 28(10), 965–979.

Fairbourn, M. (2002). Towards an organic perspective on strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 23, 561–594.

Kioll, M. J., Toombs, L. A., & Wright, P. (2000). Napolean’s tragic march home from Moscow: Lesson in hubris. Academy of Management Executive, 14(1), 117–128.

Raynor, M. E. (2007). The strategy paradox: Why committing to success leads to failure (and what to do about it). Currency. Doubleday.

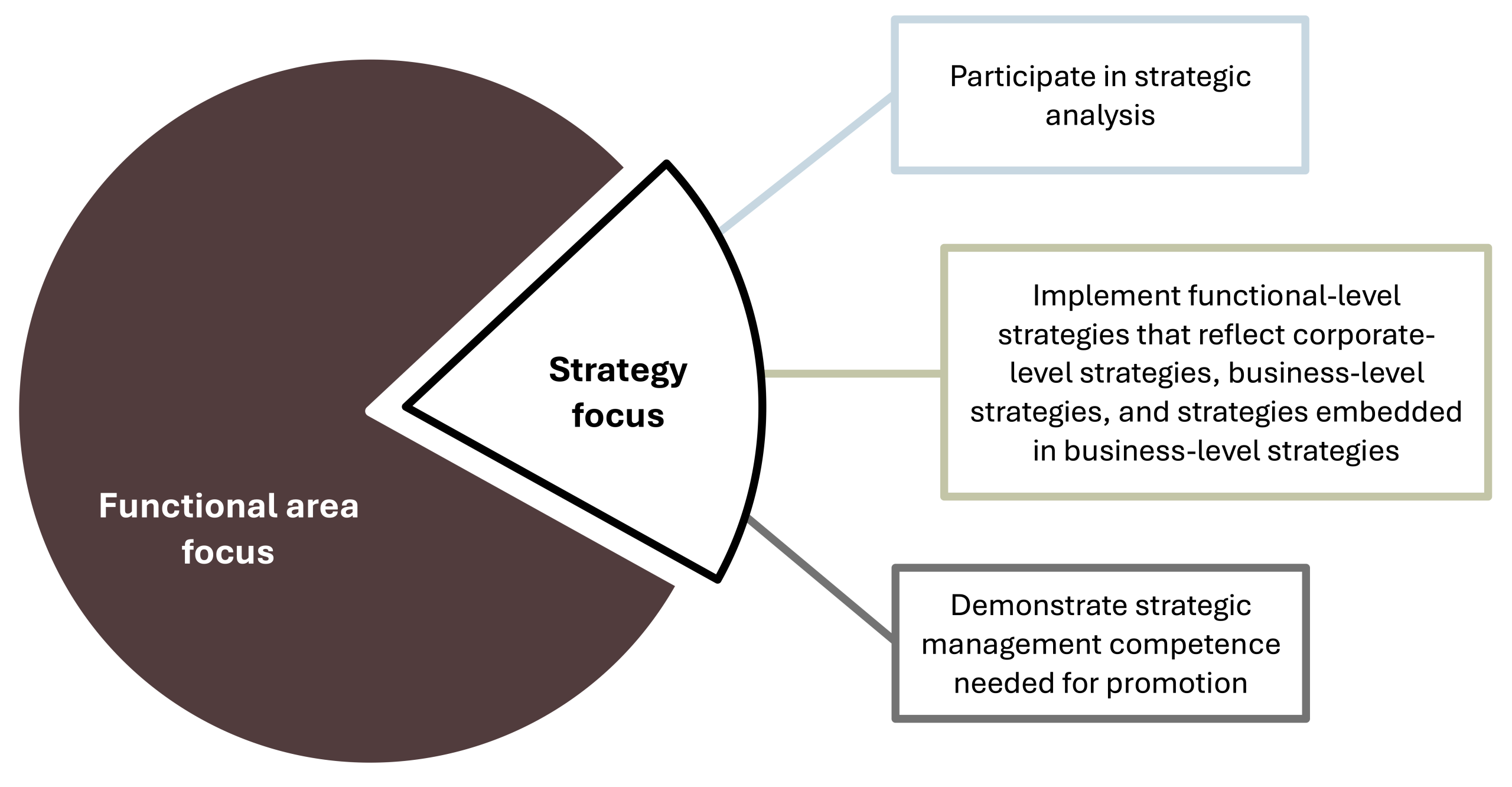

1.10 Why Strategic Management Is Valuable in All Career Settings and at All Career Stages

In section 1.9, you learned the importance of strategic management to business. It is also important to consider the ways in which strategic management is valuable to you. In doing so, we consider different career paths as well as varying career stages.

Students studying business usually obtain a broad business overview and then focus on a particular area of business. This means most business graduates are experts in a specific functional area such as accounting and information systems, business information technology and cybersecurity, finance, insurance and business law, hospitality and tourism management, human resource management, business management, management consulting and analytics, entrepreneurship, innovation and technology management, marketing, or real estate.

Many business graduates join large companies with formalized structures for strategic management. Although new business graduates in large companies usually focus on their functional areas of expertise early in their careers, there are multiple reasons that functional area experts need to understand strategic management when entering their first professional positions. In these roles, you immediately implement functional-level strategies, which address all areas of strategy, including corporate-level strategies and business-level strategies. You may also implement innovation strategies, sustainability and ethics strategies, technology strategies, and possibly multinational strategies. A thorough knowledge of each is essential to being successful as a functional expert in a functional business unit. Analysis in strategic management considers data at all levels of a company, so a functional expert such as yourself may be asked to participate in strategic management analysis as it relates to your functional area of expertise. When this opportunity arises, it is wise to demonstrate competence in strategic management, as this knowledge is needed even more in future positions.

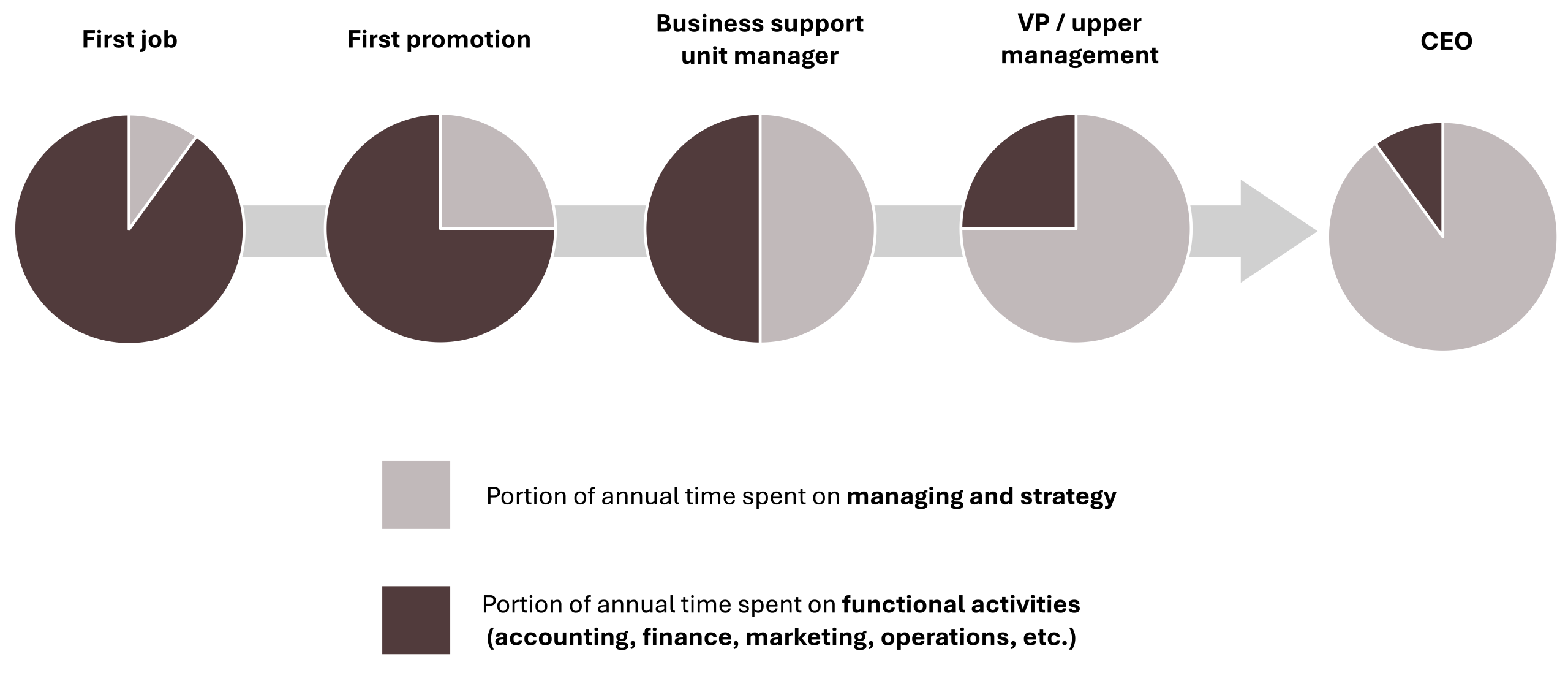

As your career progresses, the amount of time spent focusing on strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation increases. Therefore, it is important to demonstrate competence with strategic management early, placing you on the company’s radar for future promotions. To secure future positions, it is essential to demonstrate in your current position the strategic management ability needed for the next.

Some business graduates join smaller companies. In smaller firms, strategic management may be managed through more informal structures. In a smaller organization, there is an even greater chance that skills in strategic management are needed earlier in your career.

Other business graduates enter internal or external consulting roles that require competence with strategic management as a primary focus. Even if the consultation is not directly related to strategic management, consultants make presentations to business managers responsible for strategic management and organizational executives responsible for strategic leadership. It is essential to be fluent in strategic management to be competent in consulting roles.

Some business graduates already are or will become entrepreneurs. As an entrepreneur, you must understand strategic management because you may need to lead every stage of strategic management to ensure your startup is successful. It is necessary to create a competitive advantage immediately and keep that in focus as your entrepreneurial enterprise grows.

Of course, your career path may include several or all of these options. You may begin your career with a large company, then become a consultant, and then start your own business. Understanding how strategic management applies to you and your career is important to your success in any area of business throughout your career. Strategic management is not something someone else does. It will be your immediate focus in any business career.

Application

- You have now considered your career plans from the point of view of the AFI framework and through the lens of Mintzberg and Waters’s model. Now that you understand why strategic management is valuable to you in any career setting and at all stages of your career, consider:

- How specifically will you use your strategic management knowledge and skills in your first professional position after graduation?

As a new business graduate entering your first professional position at a large company, you need to understand strategic management because you will immediately implement functional-level strategies that reflect corporate-level strategy, business-level strategy, and strategies that are embedded into business-level strategy, such as innovation, sustainability and ethics, technology, and possibly multinational strategies; you may be asked to participate in strategic management analysis as it relates to your functional area of expertise; and it is wise to demonstrate competence in strategic management because this knowledge is needed in future positions. As your career progresses in a large company, the focus on strategic management increases. If you graduate and join a smaller company where strategic management is managed through more informal structure, you are likely to participate in more of the strategic management process immediately. Internal or external consultants require strategic management competence as the primary focus of your role. Entrepreneurial business graduates need to understand strategic management to ensure your startup is successful.

1.11 Conclusion

In this introduction to strategic management, you learned how a few essential terms are used in the book, including organization, business, company, firm, industry, strategic management concepts and theories, and analytical frameworks and tools. You considered what strategic management is and reviewed the analysis, formulation, implementation (AFI) framework, which guides the book. You learned an alternative and complementary approach to the AFI framework’s planned and methodical approach, involving intended, deliberate, emergent, realized, and unrealized strategies. You considered why strategic management is important to businesses. You reviewed the history of strategic management and the contemporary critique of the field. Finally, you learned how strategic management is valuable to you in all career settings and at all career stages. Now that you have learned what strategic management is, the next chapter introduces you to conducting a case analysis.

- Describe organization, business, company, firm, and industry and their relationships to each other. Give examples, and explain how your examples illustrate each.

- Explain concepts, theories, and analytical frameworks and tools and their relationships to each other. Give examples, and explain how your examples illustrate each.

- Define strategic management. How does this compare to what you expected strategic management to be before you began this course?

- Describe strategic leadership, strategic management, and strategy and their relationships to each other.

- Explain strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation and their relationships to each other.

- Describe the analysis, formulation, implementation (AFI) framework. How much of the framework can you recall without referring to the diagram? Now return to figure 1.3 and be sure you understand each element in the figure and their relationships.

- Explain the concepts of strategic issue and strategic alternative, giving an example of each. These are essential throughout the course, so understanding them now is important.

- Describe the three levels of strategy. Which level of strategy are you most likely to directly analyze, formulate, and implement in your first position after graduation?

- Explain Mintzberg and Waters’s (1985) model of strategy. How does this compare and contrast with the strategy in the AFI framework?

- Discuss why strategic management is important to businesses. What are the risks when firms do not manage strategy well?

- Describe several key events in the history of strategic management. Which events were familiar to you? Were there any that surprised you? Discuss why knowing the history of a subject important.

- Discuss a few of the critiques of strategic management. Why is a critiquing a field important?

- Describe how strategic management is relevant to you and your career.

By answering these questions robustly, you have demonstrated your thorough knowledge of this overview of strategic management. Well done!

Figure Descriptions

Figure 1.3: Circular flow chart illustrating different aspects of strategic management. The center of the circle is labeled strategic management and strategic leadership. Moving clockwise, the first category is strategic analysis (i.e., Where are we?) and includes 4 blue boxes: analyze organizational performance, analyze external environment, analyze internal environment, and determine strategic issue and alternatives. Second category is strategy formulation (i.e., Where are we going?) and includes three light green boxes representing three levels of strategy and four dark green boxes representing strategies that are embedded into business-level strategy. Light green: formulate corporate-level strategy (where to play), formulate business-level strategy (how to win/right to win), and formulate functional-level strategy. Dark green: formulate innovation strategy, formulate sustainability and ethics strategy, formulate technology strategy, and formulate international strategy. Third category is strategy implementation (i.e., How do we get there?) and includes one orange box: implement strategy.

Figure 1.4: Inverted blue pyramid that is divided into six sections. The title of the chart reads “Strategic analysis; Where are we?” From top to bottom, the sections are: analyze organizational performance, analyze external environment, analyze internal environment, synthesize external and internal analysis, determine strategic issue, and determine strategic alternatives.

Figure 1.5: Green flow chart titled “Strategy formulation: where are we going?” The chart is three levels. Topmost level represents corporate-level strategy (i.e., where to play?). Middle level represents business-level strategies and their associated strategic business units (i.e., how to win?). A list titled “Right to win?” is connected to one of the business-level strategy boxes. The list includes innovation strategy, sustainability and ethics strategy, multinational strategy, and technology strategy. The bottommost level represents functional-level strategies and their associated functional business units.

Figure 1.6: A large, gray arrow curving upward from left to right contains three labels. Left part of the arrow is labeled intended strategy. Middle part of the arrow is labeled deliberate strategy. Right part of the arrow is labeled realized strategy. A smaller purple arrow juts out from the “intended strategy” part of the original arrow and points away. It is labeled unrealized strategy. Another small purple arrow comes the right, seemingly from nowhere, and merges with the original arrow between deliberate strategy and realized strategy. This small arrow is labeled emergent strategy.

Figure 1.7: Purple pie chart illustrating two main segments titled functional area focus (roughly 75%) and strategy focus (roughly 25%). Three boxes jut out from strategy focus: (1) participate in strategic analysis, (2) implement functional-level strategies that reflect corporate-level strategies, business-level strategies, and strategies embedded in business-level strategies, and (3) demonstrate strategic management competence needed for promotion.

Figure 1.8: Five purple pie charts representing career progression from first job to CEO. Each chart shows the portion of annual time spent on (1) managing and strategy, and (2) functional activities including accounting, finance, marketing, and operations. First job shows 90% functional activities and 10% managing and strategy. First promotion shows 75% functional activities and 25% managing and strategy. Business support unit manager shows 50% functional activities and 50% managing and strategy. VP/upper management shows 25% functional activities and 75% managing and strategy. CEO shows 10% functional activities and 90% managing and strategy.

Figure References

Figure 1.1: Elon Musk follows through on Tesla’s Master Plan. Steve Jurvetson. 2016. CC BY 2.0. https://flic.kr/p/HJfr8c

Figure 1.2: Strategic leaders align strategic analysis, strategy formulation, and strategy implementation, much like fitting puzzle pieces together correctly. Kindred Grey. 2025. CC BY. Adapted from “Brain with a head outline and grey and blue puzzle pieces” by Raquel Mela (2019). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brain_with_a_head_outline_and_grey_and_blue_puzzle_pieces.jpg

Figure 1.3: The analysis, formulation, implementation (AFI) framework. Kindred Grey. 2025. CC BY.

Figure 1.4: Strategic analysis. Kindred Grey. 2025. CC BY.

Figure 1.5: Strategy formulation. Kindred Grey. 2025. CC BY.

Figure 1.6: Intended, deliberate, emergent, realized, and unrealized strategies. Kindred Grey. 2025. CC BY.

Figure 1.7: Amount of time spent on strategy in your first position as a functional area expert for a large company. Kindred Grey. 2025. CC BY.

Figure 1.8: Amount of time spent on strategy as your career progresses in a large company. Kindred Grey. 2025. CC BY.

Organization is the broadest term used to describe a specific entity and applies to entities in all sectors: private (for-profit), governmental (public), and not-for-profit (including nonprofit, nongovernmental organizations [NGOs], and voluntary organizations). Organizations in the private sector are also referred to as businesses, companies, and firms.

A business is a single company within an industry or an organization in the private sector that is engaged in commerce and aims to make a profit.

Organization in the private sector that is engaged in commerce and aims to make a profit.

Organization in the private sector that is engaged in commerce and aims to make a profit.

Industry is a group of organizations, businesses, companies, or firms that offer similar products and services and compete in the marketplace for profit.

Concepts are ideas. A collection of concepts is referred to as a theory.