9. Formulate Innovation Strategy

After engaging with this chapter, you will understand and be able to apply the following concepts to formulating innovation strategies.

- Innovation strategy

- Entrepreneurial orientation

- The importance of innovation

- The types of innovation

- Footholds

- The ways innovation relates to business-level strategies

- First movers and fast followers

- Product life cycle

- Crossing the chasm

- Cooperative moves

- Responding to innovation in the market

- Measuring innovation performance

- Why technology strategy is important to business graduates

Ultimately, this chapter equips you to analyze innovation strategy.

9.1 Introduction

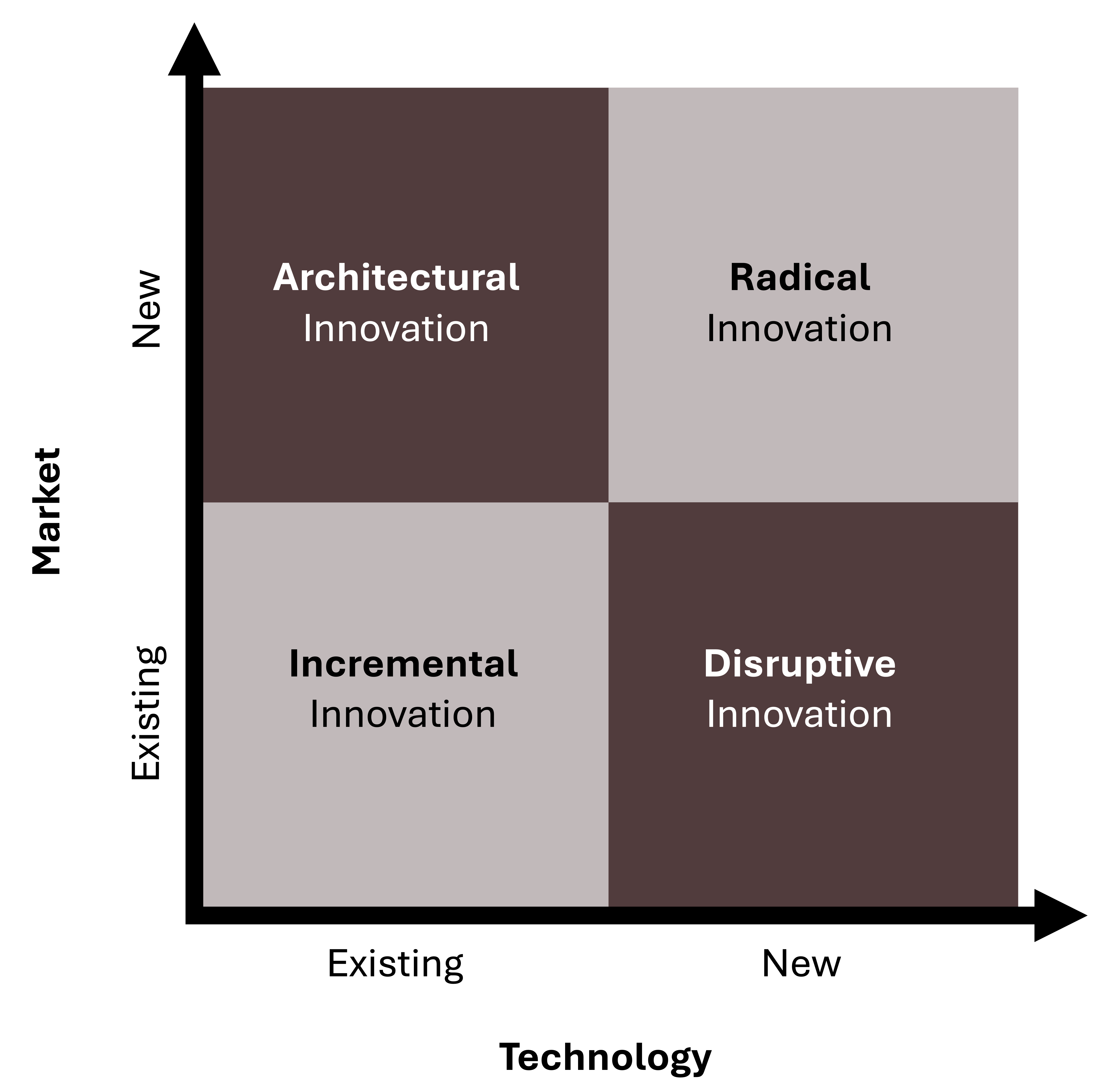

In this chapter, you first learn what innovation strategy is. Next you learn about entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and its role in innovation. This term is applied to both entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship, as well as to individuals. EO accounts for innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking. This chapter also discusses why innovation is important and the four major types of innovation. These differ along two dimensions. The first considers whether the company is innovating by creating a new market or addressing an opportunity in an existing market. The second dimension of innovation considers whether the innovation uses a new technology or takes advantage of existing technology. Incremental innovation involves entering an existing market with existing technology; disruptive innovation enters an existing market with new technology; architectural innovation enters a new market with existing technology; and radical innovation enters a new market with new technology. After considering the four types of innovation, you learn that first movers are those firms that enter a market first and fast followers enter the market after first movers pave the way. Then you learn how the four types of innovation and first movers and fast followers apply to a product’s life cycle (introduction, growth, maturity, and decline).

As this chapter continues, you learn the five stages of a company’s product adoption cycle or an industry’s technological advancement. These five stages are innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. You learn the importance of crossing the chasm as a means of sustaining a product’s growth in the market. You revisit internal development, strategic alliances, joint ventures, and mergers and acquisitions as means of cooperating with other firms. Next you learn ways of responding to innovation in the market, including multipoint competition, responding to disruptive innovations, fighting brands, co-location, and co-opetition. Then you learn how to measure a firm’s performance through the lens of innovation. Finally, you learn how to analyze innovation strategy.

9.2 Innovation Strategy

Like all strategy formulation, innovation strategy formulation answers the question “Where are we going?” Innovation strategy addresses where a firm is going as it relates specifically to innovation. All firms need to address innovation and innovation strategy.

Innovation strategy is the first strategy you learn that is embedded in business-level strategy at the strategic business unit level of a firm. Strategies that are embedded in business-level strategies address the “Right to win?” question. All companies have the ambition to win in their chosen markets. They want to gain market share, increase revenue and profit, and enter new markets and regions, among other barometers of success. However, strategy is more than a wish list of what a company would ideally want to do and achieve. Strategy is a company-specific roadmap for navigating in its industry, directing how a firm moves from its current state toward the firm’s vision.

Like all strategy, innovation strategy focuses on an outside-in perspective. Companies need to carefully monitor their external environments. They need to analyze trends and formulate strategies that are forward-looking. Robust innovation strategy takes into account the volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) nature of the firm’s external environment, where change and disruption have become the new normal.

A firm’s approach to innovation plays a crucial role in shaping its competitive advantage. A strong commitment to innovation, often reflected in a firm’s entrepreneurial mindset, drives the development of new products and services while refining existing offerings. This process of continuous improvement not only enhances the company’s market position but also expands its reach into new, often untapped, markets.

Like all strategy formulation, innovation strategy formulation answers the question of where a firm is going. Innovation strategy addresses where a firm is going as it relates specifically to innovation. All firms need to address innovation and innovation strategy. Innovation strategy is embedded in business-level strategy at the strategic business unit level of a firm. Strategies that are embedded in business-level strategies address the “Right to win?” question. A firm’s approach to innovation plays a crucial role in shaping its competitive advantage.

9.3 Entrepreneurial Orientation

An essential part of innovation, entrepreneurial orientation (EO) is a fundamental concept in strategic management and entrepreneurship, capturing the essence of how firms innovate, take risks, and proactively engage with the market to seize new opportunities. At its core, EO reflects a firm’s willingness to embrace change, challenge the status quo, and explore uncharted territories, which can drive growth and competitive advantage. By embodying a mindset that prioritizes bold strategic moves, agility, and a forward-looking perspective, companies with strong EO are better positioned to navigate uncertainty, respond to shifting market dynamics, and sustain long-term success. Understanding EO offers valuable insights into how firms can cultivate a culture of entrepreneurship to thrive in today’s dynamic business environment.

Entrepreneurial orientation is characterized by three core traits: innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking. Innovativeness represents a company’s willingness to experiment with new ideas, products, or processes. Proactiveness refers to a firm’s ability to anticipate and act on future opportunities rather than simply reacting to external changes. Risk-taking involves the willingness to invest in uncertain ventures and explore new territories, even when the outcomes are unknown. Although EO has traditionally focused on these three characteristics, two additional traits, competitive aggressiveness and autonomy, have been proposed as part of EO. However, these have sparked debate in academic circles and are excluded from this discussion so that we may focus on the core dimensions of EO that are universally recognized.

Innovativeness

Innovativeness refers to the drive to embrace creativity and experimentation. Some innovations are incremental, building on existing skills to make small improvements, while others are more radical, demanding new skills and potentially rendering old ones obsolete. The goal of innovativeness is to develop new products, services, or processes. Companies that excel in innovation typically outperform those that fail to prioritize it, gaining a competitive edge and enhancing overall performance.

Renowned for its commitment to efficiency, UPS introduced its ORION system, an innovative technology that optimizes delivery routes in real time, saving fuel and reducing delivery times. This type of advancement is particularly valuable for businesses handling time-sensitive goods, such as pharmaceuticals or fresh produce. But how do companies come up with such innovations that address their customers’ specific and complex needs?

Companies like Apple and Atlassian offer some insights. Apple frequently sends its design teams into consumer environments to better understand user pain points and needs, resulting in products that anticipate market demand. Atlassian, known for its project management tools, allows employees to dedicate a portion of their work hours to passion projects, leading to the creation of new features like Jira’s customizable workflows. These examples highlight how encouraging employee autonomy can fuel innovation, demonstrating how multiple dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation, such as autonomy and innovativeness, can work together to drive breakthrough ideas.

Proactiveness

Proactiveness refers to the ability to anticipate and act on future needs rather than merely responding to events as they unfold. Proactive organizations are opportunity-driven, identifying and capitalizing on emerging trends before competitors.

Take, for example, Tesla’s early investment in electric vehicles. Long before the market for EVs was fully established, Tesla anticipated a shift toward sustainable transportation and positioned itself as a leader in the industry.

Similarly, Shopify, recognizing the growing trend of e-commerce, rapidly adapted to the needs of small businesses by offering easy-to-use, scalable solutions before many other platforms could catch up. These companies embody proactiveness by actively seeking out opportunities in changing technological, environmental, and market conditions, allowing them to stay ahead of the curve and build strong competitive advantages.

Risk-Taking

Risk-taking involves pursuing bold actions rather than opting for conservative or cautious strategies.

A strong example of this can be seen in Netflix’s decision to transition from DVD rentals to streaming services, a move that required significant investment and foresight at a time when streaming technology was still in its infancy. This bold shift not only redefined how people consume media but also established Netflix as a global entertainment powerhouse, none of which would be possible if Netflix had not taken the risk of changing its entire business model.

While entrepreneurs and companies are often portrayed as habitual risk-takers, research shows that many do not perceive their actions as inherently risky. Instead, they employ careful planning and forecasting to mitigate uncertainty.

For instance, when Tesla decided to build its Gigafactory, the company faced massive financial and logistical challenges. However, detailed planning and strategic partnerships helped reduce the uncertainty, enabling Tesla to scale up production and dominate the electric vehicle market. Yet, as with any venture, uncertainty can never be entirely eliminated.

When BP decided to expand its oil exploration operations in the Gulf of Mexico, the company exemplified risk-taking by investing heavily in a venture fraught with political, environmental, and technical challenges. Despite the potential for high returns from gaining access to vast oil reserves, the move exposed BP to unpredictable risks, which ultimately materialized during the Deepwater Horizon disaster, which caused the largest marine oil spill in history. This incident highlighted the inherent dangers of risk-taking, as the pursuit of strategic opportunities can lead to substantial gains but also significant losses.

These examples show that, while risk-taking is essential for growth, successful entrepreneurs and firms should balance bold action with strategic foresight to increase the likelihood of long-term success.

| EO dimension | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Innovativeness | Tendency to engage in and support new ideas, experimentation, and creative processes that lead to the development of new products, services, or processes | Apple’s Apple Watch, developed through a culture of innovation and cross-functional experimentation, blending health tracking, communication, and design to redefine wearable technology |

| Proactiveness | The ability to anticipate and act on future needs rather than merely responding to events as they unfold | Tesla’s early investment in electric vehicles. Long before the market for EVs was fully established, Tesla anticipated a shift toward sustainable transportation and positioned itself as a leader in the industry. |

| Risk-taking | Involves pursuing bold actions rather than opting for conservative or cautious strategies | Netflix’s decision to transition from DVD rentals to streaming services, a move that required significant investment and foresight at a time when streaming technology was still in its infancy |

Figure 9.3: The three dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation

Intrapreneurship

Entrepreneurship is often synonymous with trailblazers who build empires from scratch—figures like Whitney Wolfe Herd, who revolutionized online dating with Bumble, or Melanie Perkins, who simplified graphic design with Canva. But the spirit of entrepreneurship is not confined to startups or garage-born businesses. In fact, some of the most impactful innovations come from individuals working within large organizations who challenge the status quo, pushing for the development of groundbreaking products or services. These employees may not be founders, but they act with the same determination and creativity to bring their ideas to fruition, often reshaping the company’s future in the process.

This form of entrepreneurship within an organization is known as intrapreneurship. Unlike traditional entrepreneurship, intrapreneurs innovate from within, navigating the complexities of large organizational structures to drive change.

For instance, 3M’s famous invention of Post-it notes didn’t come from external R&D but from an employee experimenting with new uses for a weak adhesive. Similarly, Netflix’s shift from DVD rentals to streaming content came from internal visionaries who saw the potential long before streaming was a mainstream concept.

Companies that foster intrapreneurship often gain a competitive advantage by leveraging their existing resources, capabilities, and core competencies to develop new products and services without needing to acquire or merge with external firms. Rather than solely seeking growth through acquisitions, firms like Apple and Google have created cultures that encourage employees to think and act entrepreneurially, resulting in innovations like the iPhone and Google Maps, both developed internally.

Moreover, thinking entrepreneurially isn’t just beneficial for organizations; it’s a powerful tool for personal career growth. Employees who adopt an entrepreneurial mindset often excel in navigating corporate landscapes, identifying opportunities others overlook, and positioning themselves as valuable innovators within their firms. Those who think outside the box and take initiative often find that they can climb the corporate ladder faster, all while making meaningful contributions to the company’s success.

Intrapreneurs, much like their entrepreneurial counterparts, blend creativity with strategic risk-taking, showing that entrepreneurship isn’t confined to new ventures but is also thriving within the walls of some of the world’s largest corporations.

EO Applied to Individuals

Entrepreneurial orientation applies not only to organizations but also to individuals. Traits such as risk-taking, innovation, and competitiveness, key characteristics of entrepreneurial companies, are equally important for individuals. Those who embrace creativity, are comfortable with uncertainty, and thrive in competitive environments tend to score higher in EO, which often translates to greater success when starting a business. While EO is frequently associated with high-tech startups, it is equally valuable for more traditional ventures like lawn care services or hair salons. For anyone interested, online tools are available to assess EO and better understand entrepreneurial potential.

Building an Entrepreneurial Orientation

Executives can take deliberate steps to cultivate stronger entrepreneurial orientation across their organizations, just as individuals can develop more entrepreneurial mindsets in their own roles. For executives, it’s critical to align organizational systems and policies with the key dimensions of EO. For example, compensation structures should be designed to encourage entrepreneurial behavior. Are employees rewarded for taking calculated risks, even if those risks don’t always pay off? Or does the system discourage risk-taking by penalizing failures? Corporate debt levels also play a role in shaping EO, as high levels of debt might stifle innovation by making the organization more risk averse. Thoughtfully structured debt, however, can provide the financial flexibility needed to support innovation and risk-taking.

Executives can assess their organizations’ EOs by examining various performance measures that reflect key dimensions of entrepreneurial behavior. For example, to gauge autonomy, they might track employee satisfaction and turnover rates, as organizations that encourage autonomy often see higher satisfaction and lower turnover. Innovativeness can be evaluated by measuring the number of new products or services introduced as well as the patents secured in a given year, offering tangible evidence of how effectively the company promotes creativity and experimentation.

For individuals, developing a stronger entrepreneurial orientation requires reflecting on personal attitudes and behaviors. Are you taking proactive steps rather than reacting to competitors? Are you offering fresh ideas for products or processes that could drive value for the company?

An individual employee can play a key role in enhancing EO by consistently thinking ahead, proposing new ideas, and making decisions that align with the company’s strategic goals. By doing so, they not only support the organization’s entrepreneurial culture but also position themselves as valuable contributors to its growth and success.

Application

- On a scale of 1–10, with 1 being low and 10 being high, rate yourself on innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking.

- Of these three key areas of EO, are there any you would like to challenge yourself to expand?

- Considering your ratings, how likely are you engage in entrepreneurial activity at some point in your career?

- Considering your ratings, how likely are you engage in intrepreneurial activity at some point in your career?

Entrepreneurial orientation, an essential part of innovation, is characterized by three core traits: innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking. Innovativeness refers to the drive to embrace creativity and experimentation. Proactiveness refers to the ability to anticipate and act on future needs rather than merely responding to events as they unfold. Risk-taking involves pursuing bold actions rather than opting for conservative or cautious strategies. Intrapreneurship refers to individuals acting entrepreneurially within a company. Entrepreneurial orientation applies not only to organizations but also to individuals. Executives can take deliberate steps to cultivate a stronger entrepreneurial orientation across their organizations, just as individuals can develop more entrepreneurial mindsets in their own roles.

Innovation is essential for firms to maintain a competitive edge. Companies that continuously innovate are better positioned to capture new markets, improve products, and outpace competitors, while firms that remain stagnant risk losing customers and market share. A strong EO helps firms continuously seek out new opportunities and innovate, which is crucial for staying competitive in dynamic markets.

Bibliography

Certo, S. T., Connelly, B., & Tihanyi, L. (2008). Managers and their not-so-rational decisions. Business Horizons, 51(2), 113–119.

Certo, S. T., Moss, T. W., & Short, J. C. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation: An applied perspective. Business Horizons, 52(4), 319–324.

Choi, A. S. (2008, April 16). PCI builds telecommunications in Iraq. Bloomberg Businessweek. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2008-04-15/pci-builds-telecommunications-in-iraq

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172.

Muthaiyah, S. (2023). Entrepreneurial orientation and open innovation promote the performance of services SMEs: The mediating role of cost leadership. Administrative Sciences, 13(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13010001

Pisano, G. P. (2015, June). You need an innovation strategy. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/06/you-need-an-innovation-strategy

Simon, M., Houghton, S. M., & Aquino, K. (2000). Cognitive biases, risk perception, and venture formation: How individuals decide to start companies. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(2), 113–134.

9.4 Why Innovate?

Innovation is a critical strategy for maintaining a competitive edge in rapidly evolving industries. Companies that become complacent risk losing market share to more agile competitors who are constantly pushing boundaries. An innovation-driven approach, paired with a strong entrepreneurial orientation, helps companies keep customers engaged and returning for the latest products or services.

Consider the tech industry, where companies like Apple and Samsung consistently release new versions of their smartphones with enhanced features like more powerful processors, better camera quality, or advanced software capabilities. This approach drives consumer demand, encouraging people to upgrade regularly to the latest model. In a similar fashion, streaming platforms like Netflix continuously innovate by adding interactive content and personalized recommendations, keeping users engaged and attracting new subscribers.

The automotive industry also relies heavily on innovation to stay relevant. Each year, manufacturers introduce updated models with improved designs, advanced safety features, and cutting-edge technology like electric powertrains or autonomous driving capabilities. Tesla, for example, has revolutionized the car market with its electric vehicles and over-the-air software updates, making continuous innovation a cornerstone of its success.

Even in fields like pharmaceuticals, innovation is essential. Companies invest heavily in research to develop new treatments for chronic diseases, such as cancer or Alzheimer’s, ensuring they remain at the forefront of life-saving medical advancements. Without continuous innovation, companies risk falling behind and losing their competitive positions, regardless of the industry.

Innovation is often the backbone of strategy for new startups across various industries, particularly in tech and consumer services. For instance, companies in renewable energy or electric mobility may develop groundbreaking battery technologies or new charging infrastructures that solve consumer needs and disrupt existing markets. These innovations are the engines that propel companies forward, allowing them to carve out new spaces in competitive markets.

While innovation is critical, it doesn’t negate the need for a clear business-level strategy, whether that takes the form of focused cost leadership, broad cost leadership, focused differentiation, broad differentiation, best cost, or blue ocean. A firm must still define its competitive approach to ensure the success of its innovative offerings. There is a success-critical role for innovation in all business-level strategy.

Startups introducing unique, high-demand products or services often employ a differentiation strategy, setting premium prices due to limited competition. For instance, Tender Food, founded in 2020, specializes in plant-based meat alternatives that closely mimic the taste and texture of traditional meats. By utilizing innovative fiber-spinning technology, Tender Food creates a unique and healthier plant-based meat, such as beef short ribs and chicken breasts, appealing to consumers seeking sustainable and health-conscious options. This distinct technology allows Tender Food to position itself as a leader in the plant-based food industry, justifying premium pricing for its products.

The famous saying “He who hesitates is lost,” credited to the eighteenth-century writer Joseph Addison, holds significant truth in today’s fast-moving business landscape. Executives often face overwhelming choices, but hesitation can be costly, especially in environments where rapid decision-making is crucial. Many industries now operate in conditions of hyper-competition, where the speed of competitive moves and countermoves makes it difficult to sustain a lasting competitive advantage. Under these circumstances, it is better to make a timely, reasonable decision than to wait for the perfect one, which might never materialize.

In addition, the value of continuous learning emphasizes the importance of a “take action” mindset. Business success often depends not on executing flawless moves but on learning from a series of strategic decisions and adjusting along the way. Sometimes decisive action can yield advantages, even when the decisions are made with incomplete information. Startups like Zoom capitalized on this during the pandemic by quickly scaling their services, seizing the opportunity before competitors had fully adapted to the surge in demand. These companies exemplify how timely decisions, combined with innovation, can lead to significant market gains in fast-paced industries.

Innovation is a critical strategy for maintaining a competitive edge in rapidly evolving industries. Companies that become complacent risk losing market share to more agile competitors who are constantly pushing boundaries. An innovation-driven approach, paired with a strong entrepreneurial orientation, helps companies keep customers engaged and returning for the latest products or services. Many industries now operate in conditions of hyper-competition, where the speed of competitive moves makes it difficult to sustain a lasting advantage. Under these circumstances, it is better to make a timely, reasonable decision than to wait for the perfect one, which might never materialize. The value of continuous learning emphasizes the importance of a “take action” mindset.

Bibliography

Futterknecht, P., & Hertfelder, T. (2023). Data, disruption and digital leadership: How to win the innovation game (1st ed.). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-41601-0

Kreiterling, C. (2023). Digital innovation and entrepreneurship: A review of challenges in competitive markets. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-023-00320-0

Lee, J., Park, J. S., & Lee, J. (2020). The impact of multimarket competition on innovation strategy: Evidence from the Korean mobile game industry. Journal of Open Innovation, 6(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6010014

9.5 First Movers and Fast Followers

In the competitive landscape, companies must decide how best to approach new market opportunities. Two common strategies are being a first mover or a fast follower. A first mover is a company that enters a new market or launches a new product before any competitors, aiming to establish an early advantage. A fast follower is a firm that enters the market immediately after the first mover.

First movers are the pioneers who introduce new products or services to the market, aiming to capture customer attention and establish strong market position before competitors emerge. This approach requires significant investment and a willingness to face uncertainty, as these firms must educate the market as to what they are offering and navigate uncharted territory. In contrast, fast followers enter the market after the first movers have paved the way, learning from their experiences and improving upon the original offering. Each strategy comes with its own set of advantages and challenges, and the choice between them depends on a firm’s resources, capabilities, core competencies, and risk tolerance.

The concept of first-mover advantage draws parallels from military strategy, where the objective is to strike first and gain a dominant position before competitors can respond. In business, this means entering a new market or launching a new product before others, capturing customer attention and shaping market expectations. However, the decision to be a first mover also carries risks, as early entrants must face skepticism or challenges that later entrants can avoid.

The well-known saying “the early bird gets the worm” suggests that acting early can offer distinct advantages. In business, being the first mover into a market can help a company gain a competitive edge that may be difficult for later entrants to overcome. First-mover advantage occurs when a firm’s initial move allows it to dominate the market by establishing strong brand recognition, customer loyalty, or technological leadership.

For example, Apple’s early introduction of the user-friendly personal computer in the 1980s built a reputation for creativity and innovation that continues to this day. Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) was the first Western fast-food chain to enter China, building strong relationships with local officials, which allowed it to become the top fast-food chain in that market. Genentech, a biotechnology company focused on using DNA to produce medicine, played a pioneering role in biotechnology, which helped it overcome traditional barriers to entry in the pharmaceutical industry and become highly profitable. In each of these cases, being the first mover gave these firms a distinct advantage that contributed to their long-term success.

Being a first mover is inherently risky, and companies cannot be certain consumers will embrace their offerings. Being first to the market can still yield valuable organizational learning and competitive insights, even if the product itself fails. For instance, Apple’s Newton, an early attempt to enter the personal digital assistant market, ultimately failed financially, as did Google’s initial foray into digital glasses. However, Apple and other first movers gained crucial knowledge about market demands, technological hurdles, and consumer behavior, which they could leverage in future innovations. Apple, for example, applied insights from the Newton to later products, eventually leading to the groundbreaking success of the iPhone and iPad. By learning from earlier missteps, first movers can refine their approaches, potentially leading to new and successful entries as first movers in other markets. Meanwhile, later entrants benefit from observing both the failures and successes of first movers, enabling them to refine or replicate these innovations more affordably. For example, companies like Sony and Samsung quickly followed Apple’s AirPods with their own wireless earbuds, building on Apple’s initial market insights and successes to create competing products.

First movers must also commit sufficient resources to following through on their initial advantage. For example, RCA and Westinghouse were early leaders in LCD display technology, but they failed to invest in the development and commercialization of their innovations. Today, they are not significant players in the flat-screen market, which supplies displays for everything from laptops to medical devices. Instead, companies such as Samsung, LG Display, and BOE Technology have emerged as top leaders in LCD display technology, dominating the market with their advanced research, production capabilities, and global distribution networks.

Research offers mixed conclusions about the benefits of being a first mover. Some studies suggest that a first mover typically enjoys an advantage for about a decade, while others argue that the advantages are minimal or short-lived. The key for executives is to assess whether a first move will create a sustainable competitive advantage. First moves that leverage strategic resources, such as patented technologies, are harder for competitors to replicate and thus are more likely to succeed. For example, Pfizer’s patent on Viagra gave it a monopoly in the erectile dysfunction market for five years, and even after rivals entered the market, Viagra remains a significant revenue generator for the company, earning about $1.9 billion annually.

Conversely, first movers that do not rely on strategic resources are more easily imitated. E-Trade Group’s introduction of the portable mortgage, which allowed customers to transfer a mortgage when buying a new home, lacked protection from imitation by larger banks. As a result, even if the idea had gained traction, it could have easily been replicated, limiting E-Trade’s ability to profit from being the first mover.

Application

- Describe a product that you like that is the result of a company following a first mover strategy. Discuss the advantages the company has by being a first mover.

- Describe a product that you like that is the result of a company following a fast follower strategy. Discuss the advantages the company has by being a fast follower.

| Benefits | Risks |

|---|---|

| First mover | |

| Early market dominance, establishing strong brand recognition | High investment costs (R&D, marketing, education) |

| Technological leadership or innovation | Uncertainty and risk of market rejection or failure |

| Customer loyalty and potential for a long-term competitive edge | Competitors can learn from mistakes and avoid early pitfalls |

| Ability to shape market expectations and industry standards | Must educate the market and create demand from scratch |

| First-mover advantage (for example, intellectual property or exclusive contracts) | Early products may fail, resulting in financial loss or missed opportunities (for example, the Apple Newton) |

| Fast follower | |

| Lower risk, as they learn from the mistakes and successes of first movers | Lack of market leadership and potentially weaker brand recognition |

| Can improve upon existing products, offering enhanced features or lower costs | Risk of being perceived as imitative or lacking innovation |

| Reduced development costs from the adoption of proven technology and models | May face strong competition from the first mover or other followers |

| Faster market entry with established demand | Less control over market direction and customer perception |

| Ability to benefit from first-mover insights without bearing the full cost of market creation | Missed opportunity to set industry standards or gain early brand loyalty |

Figure 9.8: First mover and fast follower strategies

A first mover is a company that enters a new market or launches a new product before any competitors, aiming to establish an early advantage. A fast follower is a firm that enters the market immediately after the first mover. There are benefits and risks to both approaches. The decision to be a first mover should be carefully evaluated based on whether the move offers the potential for a lasting competitive advantage. Without the right resources and strategic planning, first-mover status may offer only a temporary edge.

Being the first to enter a market can offer significant benefits, such as brand dominance and customer loyalty. However, it also comes with risks, including the costs of educating the market and the uncertainty of whether the product will be widely accepted. Later entrants can learn from a first mover’s mistakes and refine their own offerings.

Bibliography

Leiberman, M. B., & Montgomery, D. B. (1998). First-mover advantages. Strategic Management Journal, 9, 41–58.

9.6 Innovation Framework: Four Types of Innovation

In this section, you learn an innovation framework that considers four types of innovation that firms can leverage to drive growth and competitive advantage: incremental, disruptive, architectural, and radical innovation. Each type varies based on two key factors: whether it addresses an existing market or creates a new one and whether it utilizes existing technology or introduces new technology. Understanding these distinctions helps companies strategize how to innovate effectively, depending on their goals and market conditions.

Incremental Innovation

Incremental innovation involves enhancing an existing product or service by making improvements based on current technology and targeting the existing market. In the automotive industry, for example, incremental innovations take the form of yearly updates to car models, such as improved fuel efficiency, updated safety features, or minor design tweaks. These changes don’t create new markets but instead refine the product using established technologies to offer a better version to existing customers.

| Company | Example |

|---|---|

| Toyota | Toyota continuously updates its vehicles, such as by adding advanced driver-assistance systems or improving hybrid engine performance. |

| Samsung | Samsung’s Galaxy smartphones are incrementally improved with better screen technology, faster processors, and enhanced camera capabilities. |

| Coca-Cola | Coca-Cola introduces new variations of its drinks, such as Coca-Cola Zero Sugar and smaller, more convenient packaging sizes. |

Figure 9.10: Incremental innovation examples

Disruptive Innovation

According to a 2015 article by Christensen, Raynor, and McDonald, disruptive innovation occurs when a product or service initially enters a market by catering to an often underserved segment, often offering a simpler, more affordable solution than existing options. Over time, this innovation improves, eventually displacing established competitors. The key aspect of Christensen’s definition is that disruptive innovations begin by targeting overlooked or low-end consumers before challenging mainstream markets.

However, the term disruptive innovation has often been misunderstood or misapplied. Many products labeled as disruptive are not. According to Christensen, true disruptive innovations initially underperform in comparison to established products but appeal to customers who value new dimensions, such as simplicity or lower cost.

A classic example is Netflix. When it first launched, Netflix’s mail-order DVD rental service catered to a niche of customers who valued convenience over visiting brick-and-mortar video rental stores like Blockbuster. Over time, as internet speeds improved and streaming technology developed, Netflix moved upmarket, disrupting the entire entertainment industry and leading to the downfall of video rental stores.

In contrast, products like Apple’s iPad, often cited as disruptive, don’t fully align with Christensen’s definition. The iPad was a high-end, well-performing product at launch. While it impacted the laptop market, it didn’t follow the typical path of targeting low-end or overlooked consumers before dominating the mainstream.

Christensen’s perspective emphasizes that disruptive innovations don’t succeed by merely being better than existing products; they succeed by reshaping the competitive landscape, starting in less-demanding markets and moving upward. For example, digital cameras began with lower-quality images and slower performance compared to traditional film, appealing mainly to niche market segments. As the technology advanced, they improved in quality and convenience, ultimately surpassing film cameras and transforming the photography industry. This shift led to the decline of film giants like Kodak, who struggled to adapt. True disruptive innovations can challenge and replace incumbents by fundamentally altering how businesses and customers operate within the industry.

Below are several examples of disruptive innovation.

- The rise of tablet computers has affected laptop sales due to their greater portability and multifunctionality. While reading books on traditional computers can be uncomfortable, devices like the iPad, Nook, and Kindle offer a more convenient experience and have become favored by textbook publishers.

- Numerous stores that depended on compact disc (CD) sales closed when downloadable digital media revolutionized the music industry. Prior to this, CDs had replaced vinyl records and cassette tapes because of their better durability and sound quality. Now, music subscription services like Spotify and Apple Music are taking the place of digital downloads. What emerging technology might eventually replace these subscription models?

- Digital cameras transformed the photography industry by providing immediate results and removing the need for film development. More recently, high-quality cameras on smartphones have disrupted the digital camera market.

- The rise of personal computers challenged the supremacy of mainframes, allowing individuals to own computers in their homes.

- LED lights, a more recent technology, are gradually replacing incandescent bulbs by capturing the existing market.

Typically, disruptive innovations start with a small, niche audience of early adopters and gradually gain traction as the product improves. For example, digital cameras were initially slow and produced lower-quality images compared to traditional film, limiting their appeal. However, as the technology advanced, digital cameras gradually won over even the most loyal film users. The iPad serves as another example, but with a different trajectory. Unlike most disruptive innovations, the iPad was an immediate success, quickly gaining widespread popularity across various demographics. Its intuitive design, portability, and versatile functionality allowed it to create a new category of devices (tablets), appealing to consumers, professionals, and educational institutions from the outset.

For companies considering disruptive innovation, patience and resilience are key. Growth may be slow at first, but the ability to navigate the initial period of low adoption is crucial to long-term success. Firms need to ensure they have the resources, capabilities, and core competencies to weather this slow build while improvements are made and a broader customer base develops.

Architectural Innovation

Architectural innovation is about transforming familiar technologies into new formats, often unlocking markets that didn’t previously exist. By reimagining the structure or configuration of a product or service, companies can create offerings that appeal to entirely new audiences. A notable example is the smartwatch, which repurposed existing smartphone technology into a wearable device, creating a new consumer category. By integrating product capabilities like fitness tracking, notifications, and health monitoring into a compact, wrist-worn format, companies like Apple and Samsung redefined the potential of wearable tech and broadened the appeal of digital connectivity.

This form of innovation thrives on reshaping existing technologies in creative ways. Companies don’t need to invent something entirely new; they just need to rethink how their current technologies can be used in different contexts. By doing so, firms can tap into new markets and meet the needs of consumers who may have been uninterested in the original product. Architectural innovation allows businesses to expand without reinventing the wheel—simply by giving old technologies a fresh, compelling new form.

Below are examples of effective architectural innovation.

- Peloton combines existing technologies such as bicycles, the internet, and communication tools to attract new customers who might not have purchased an exercise bike otherwise.

- Some companies have utilized solar cell technology to create small sources of rechargeable outdoor lighting, attracting a new group of consumers who use these eco-friendly lights to decorate their yards.

- Copiers were once large, costly machines designed for use in large offices. Canon and other companies redesigned these machines to be compact and desktop-friendly, opening up a new market for personal copier/printers.

Radical Innovation

Radical innovation occurs when entirely new technologies are used to create products or services that open up new markets. A prime example is the invention of the airplane, which revolutionized transportation by making long-distance travel feasible in ways that were previously unimaginable. Before air travel, a trip from New York to San Francisco could take weeks by car or train, but the airplane dramatically shortened this time, transforming the way people and goods moved across the world.

Radical innovation isn’t just about introducing something new; it’s about reshaping the landscape of what’s possible. By utilizing groundbreaking technologies, companies can reach new consumers and create markets that didn’t previously exist.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a defining innovation of the current business landscape. Companies that respond effectively to disruptive, new, and emerging technologies, such as AI, are engaging in radical innovation. NVIDIA’s CUDA platform opened up the parallel processing power of GPUs to general-purpose computing, enabling GPUs to complete complex AI and deep learning tasks. In healthcare, AI models analyze data to identify early signs of diseases before symptoms appear. AI in finance is used in algorithmic trading to analyze market data, predict market movements, and execute trades at optimal times.

Once a firm successfully launches a radically innovative product or service, they often shift to a strategy of incremental innovation, making continuous improvements to enhance performance and attract even more customers. For example, after the initial development of smartphones, which is an example of radical innovation, companies like Apple and Samsung used incremental innovation to add features like better cameras and faster processors, keeping consumers engaged and boosting sales. Radical innovations create the foundation, but it’s the steady stream of enhancements that ensures long-term success.

Below are examples of radical innovation in different industries.

- Pharmaceutical researchers frequently develop groundbreaking products through innovative combinations of chemicals designed to treat medical conditions, which in turn draw new customers. For example, Aricept, a medication co-marketed by Eisai and Pfizer for managing Alzheimer’s symptoms, has expanded market opportunities.

- Apple’s AirPods represent a radical innovation, as the company created a wireless earpiece capable of receiving Bluetooth signals. Today, it’s common to see people wearing AirPods, a shift from the past when wired earphones were more commonly used.

- The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine utilizes electromagnetic forces, rather than X-rays, to capture internal images of the body. This innovation created an entirely new market, with hospitals investing in these machines to expand their diagnostic abilities.

Application

- Incremental innovation involves enhancing an existing product or service by making improvements based on current technology and targeting the existing market.

- Describe a product that you like that is the result of a company following an incremental innovation strategy. Discuss the advantages the company has by following an incremental innovation strategy. Explain how the product is an existing product in an existing market.

- Disruptive innovation occurs when a product or service initially enters a market by catering to an often underserved segment, typically offering a simpler, more affordable solution than existing options.

- Describe a product that you like that is the result of a company following a disruptive innovation strategy. Discuss the advantages the company has by following a disruptive innovation strategy. Explain how the product is a new product in an existing market.

- Architectural innovation is about transforming familiar technologies into new formats, often unlocking markets that didn’t previously exist.

- Describe a product that you like that is the result of a company following an architectural innovation strategy. Discuss the advantages the company has by following an architectural innovation strategy. Explain how the product is an existing product in a new market.

- Radical innovation occurs when entirely new technologies are used to create products or services that open new markets.

- Describe a product that you like that is the result of a company following a radical innovation strategy. Discuss the advantages the company has by following a radical innovation strategy. Explain how the product is a new product in a new market.

There are four types of innovation that firms can leverage to drive growth and competitive advantage: incremental, disruptive, architectural, and radical. Each type varies based on two key factors: whether it addresses an existing market or creates a new one and whether it utilizes existing technology or introduces new technology. Incremental innovation involves enhancing an existing product or service by making improvements based on current technology and targeting the existing market. Disruptive innovation occurs when a product or service initially enters a market by catering to an often underserved segment, offering a simpler, more affordable solution than existing options. Over time, this innovation improves, eventually displacing established competitors. The key is that disruptive innovations begin by targeting overlooked or low-end consumers before advancing to challenge mainstream markets. Architectural innovation is about transforming familiar technologies into new formats, often unlocking markets that didn’t previously exist. Radical innovation occurs when entirely new technologies are used to create products or services that open up new markets.

Bibliography

Christensen, C. M., Raynor, M. E., & McDonald, R. (2015, December). What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation

9.7 Footholds

Just as rock climbers rely on footholds for stability and progress when ascending steep cliffs, firms use footholds to secure positions in markets where they are not yet established. In business, a foothold refers to a small but strategic entry point that a company deliberately creates in an unfamiliar market. This initial presence allows the firm to gather market insights, test the waters, and prepare for potential expansion. Footholds are factors in architectural and radical innovations, as they are the two types of innovation that involve entering new markets.

For instance, a company may acquire small local firms or open a limited number of stores in a new region as a way of gaining a foothold. This approach allows the company to understand local consumer behavior and competition without committing to large-scale operations right away. Once a foothold is secure, the firm can build from this position, gradually scaling up its presence and influence in the new market.

Below are examples that illustrate the use of footholds.

- When IKEA enters a new country, like Japan, it typically opens only one store initially. This first location serves as a showcase to build the brand’s presence, and additional stores are opened once the brand has gained recognition (Hambrick & Fredrickson, 2005).

- Pharmaceutical leader Merck gained a strong position by acquiring SmartCells Inc., a company working on a potential new treatment for diabetes.

- The concept of a foothold is also relevant in warfare, where armies establish new positions in previously unoccupied territories. During World War II, the Allied Forces used Normandy, France, as a strategic base to launch their advance against German forces.

Many companies strategically use footholds to gain small but intentional presences in new markets before making larger commitments. A foothold provides a low-risk way to explore market dynamics and refine offerings without fully diving in (Upson et al., 2012).

Tech companies also use footholds to explore emerging markets. Microsoft often enters new industries by acquiring smaller startups, as it did with its purchase of Mojang, the developer of the popular game Minecraft. This foothold allowed Microsoft to enter the gaming space more robustly, later expanding its Xbox offerings and gaming services. Similarly, Amazon initially secured a foothold in the grocery market by acquiring Whole Foods. This strategic entry allowed Amazon to explore the grocery industry with an established brand while integrating its own e-commerce and logistics expertise. By using these smaller, calculated steps, companies like Microsoft and Amazon can test the waters in new markets before fully scaling their operations.

Application

- Think about your own personal experience in school. When have you made a small but strategic entry point in an unfamiliar area?

- Describe a time when you have gained a foothold. Perhaps it was with a new social group of friends. Maybe you made it happen by playing club sports. Have you gotten a foothold in a new subject, such as strategic management?

- Discuss the advantages the foothold gave you.

Bibliography

Christensen, C. M., Raynor, M. E., & McDonald, R. (2015, December). What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation

Hambrick, D. C., & Fredrickson, J. W. (2005). Are you sure you have a strategy? Academy of Management Executive, 19(4), 51–62.

Johnson, S. (2010, September 25). The genius of the tinkerer. The Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703989304575503730101860838.html

Ketchen, D. J., Snow, C., & Street, V. (2004). Improving firm performance by matching strategic decision making processes to competitive dynamics. Academy of Management Executive, 19(4), 29–43.

Rosmarin, R. (2006, February 7). Nintendo’s new look. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/2006/02/07/xbox-ps3-revolution-cx_rr_0207nintendo.html

Upson, J., Ketchen, D. J., Connelly, B., & Ranft, A. (2012). Competitor analysis and foothold moves. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 93–110.

9.8 Innovation and Business-Level Strategy

We often think of innovation as applying to the products that high-tech companies produce, with innovation being a central focus for these companies. High tech companies typically follow a differentiation strategic market position and either a focused or broad strategic market size, choosing a broad differentiation business-level strategy or a focused differentiation strategy. However, those firms are not the only firms that focus on innovation. In fact, all companies need an innovation strategy. Innovation strategy is central to organizations that follow any type of business-level strategy.

Differentiation

For firms that follow a broad or focused differentiation strategy, innovation is typically more focused on product and service innovations. Innovation drives differentiation more externally through customers.

A part of the innovation strategy for firms that follow these strategies is high investments in R&D to fuel continuous product and service innovation. This is a clear choice, as they are operating in a business environment where customers want continuous upgrades to their products and services.

In high-tech industries, customers want new features and new product innovations. In the high-end fashion market segment for example, consumers want the latest fashion innovations. They also expect exceptional service and individualized attention.

Companies following focused or broad differentiation business-level strategies are able to demand higher prices for the latest products and services. They use the higher profit margins on their products and services to ensure a return on their R&D investments. Because of this, they can create new products and continuously introduce new or improved services to sustain their competitive advantage.

These firms focus on being the first to market with a new product or service. Firms that follow a differentiation strategy often aim to be first movers.

While all firms may use different types of innovation at different times, companies that approach strategic market position by targeting differentiation and cost leadership use the four types of innovation differently. Companies following a focused or broad differentiation business-level strategy use each type of innovation—incremental, disruptive, architectural, and radical—to innovate in customer-facing product and service innovation.

Cost Leadership

For firms that follow a cost leadership business-level strategy, either broad or focused, innovation is typically more internally focused on process optimization in support of lean operations that reduce costs.

Firms that follow a broad or focused cost leadership strategy focus on reducing costs in their firm value chains. To optimize operational efficiency and reduce costs, they focus on process innovation in their primary activities, such as in their inbound and outbound logistics and standardizing operations. They may also focus on doing the same in manufacturing, warehousing, and distribution. Because they have smaller profit margins, these companies must focus on enhancing operational excellence.

Firms that follow broad or focused cost leadership business-level strategies often aim to be fast followers. Their low investments in R&D do not generally support a first-mover approach. Industry leading cost leadership companies capitalize on innovations that other first movers have made by being fast followers.

All firms may use different types of innovation at different times. Companies that follow broad or focused cost leadership strategy use incremental, disruptive, architectural, and radical innovation to innovate internally, focusing on process innovation, operational efficiency, and cost reduction.

Application

- Describe how a value chain analysis would assist an analysis of innovation for a company following a cost leadership approach to strategic market position.

- Review figure 5.9 to refresh your memory of a value chain analysis. Explain which primary and support activities offer the most potential for process optimization in support of lean operations that reduce costs. Illustrate your answer with an example of a company and discuss your rationale.

For firms that follow either a focused or broad differentiation strategy, innovation is typically more focused on product and service innovations. Innovation drives differentiation more externally through customers. These firms focus on being the first to market with a new product or service. Firms that follow a differentiation strategy often aim to be first movers. For firms that follow cost leadership approaches, either broad or focused, innovation is typically more internally focused on process optimization in support of lean operations that reduce costs. Industry-leading cost leadership companies capitalize on innovations that other first movers have made by being fast followers.

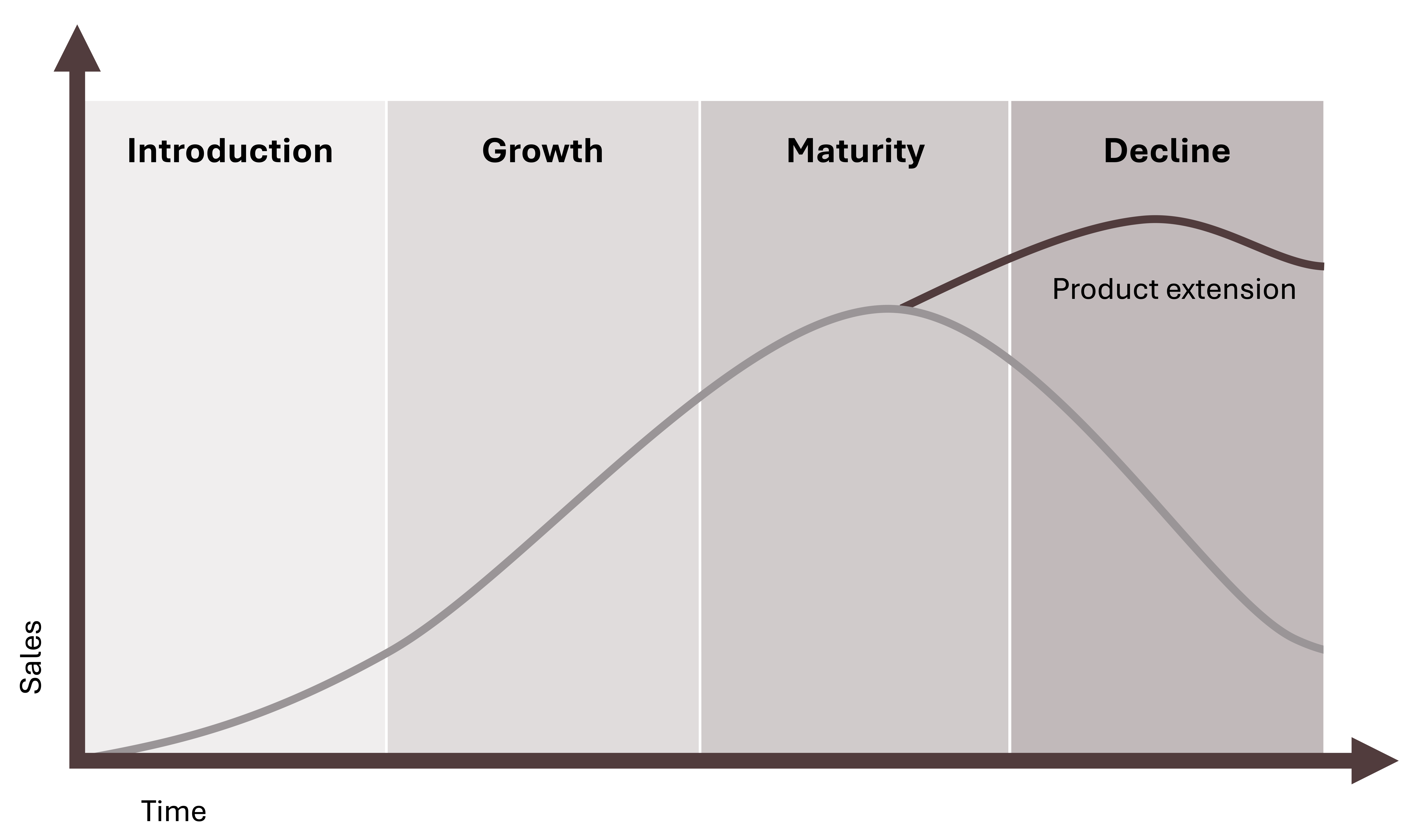

9.9 Product Life Cycle

When a new product is introduced to the market, it typically follows a progression through four distinct stages that represent the product life cycle. These stages are the same for all types of products, from high-tech gadgets like virtual reality headsets to everyday items like cleaning solutions. Product life cycle stages apply primarily to architectural innovation (a product in a new market that uses an existing technology), radical innovation (a product in a new market that introduces new technology), and disruptive innovation (a product introduced in a new market that uses new technology). The four product life cycle stages are introduction, growth, maturity, and decline.

Introduction

In stage one, the product is launched with hopes of gaining traction in the market. Sales are usually slow at this stage as customer awareness for the product builds.

When the product is new to consumers, companies follow a first mover’s approach, observing the first to introduce a product. Stage one of the product life cycle applies primarily to those types of innovation that introduce a product into a new market and/or uses new technology. This includes three types of innovation: architectural innovation, disruptive innovation, and radical innovation.

For example, the sustainable brand Patagonia, known for its eco-friendly outdoor clothing, introduced a line of clothing made from recycled materials, representing architectural innovation. The company entered a market of environmentally-conscious consumers by using existing materials but offering an innovative product that focused on sustainability. This approach helped Patagonia stand out as a leader in the sustainable fashion industry.

Growth

Then in stage two, as the product begins to gain popularity, sales begin to steadily increase. Competitors, including many fast followers, enter the market, though competition remains manageable, allowing room for growth. For both the original product designer and imitators, conducting a Porter’s Five Forces analysis at this stage is valuable to assess the threat of new entrants. This analysis helps the original designer understand how to maintain their competitive edge, while imitators can identify opportunities to differentiate or compete on cost. By understanding the dynamics of competition, barriers to entry, and the potential power of suppliers and buyers, both groups can strategically position themselves for sustained success in the growing market.

Maturity

Once a product market has grown rapidly and sales have increased in the growth stage, the product reaches maturity in the market. The early maturity stage is characterized by continued growth and sales. Then market saturation is reached, and sales reach their peak in the later phase of the maturity stage. By the end of the maturity stage, market growth slows as the market becomes saturated. Competition intensifies, and a shakeout occurs, where some competitors exit or merge with others. Conducting a Porter’s Five Forces analysis to analyze the threat of substitute products is also valuable at this stage.

Decline

Finally, the product life cycle ends in a stage of decline. Sales start to drop as the product loses relevance or market demand decreases. Fewer competitors remain, and firms begin looking for exit strategies or ways to consolidate. During the decline stage, the product’s placement on the Boston Consulting Group matrix can give executives initial information about whether to divest the product line from their portfolio.

This life cycle can be visualized as a bell curve, with sales starting low during the introduction stage, rising during the growth stage, peaking during the maturity stage, and eventually falling during the decline stage. Notice the bell curve is not symmetrical, as the product life cycle curve for stage one, product introduction, rises much more slowly than stage two, the growth stage. First movers who introduce a new product must be prepared to weather stage one and continue to invest in the product and its production as well as marketing so that they reach stage two, growth, when the life cycle curve is much steeper. During stage one, companies must create capacity in all areas of both the firm and industry value chains to be ready to adequately deal with the growth stage of the product.

Product Life Cycle Extension

To avoid or delay the decline stage of a product’s life cycle, companies often relaunch their products by introducing updated or improved versions. This is an example of incremental innovation (introducing products in existing markets using existing technology), and it helps revitalize interest and effectively restarts the product life cycle. For example, Apple frequently updates its iPhone with new features to maintain consumer demand, and car manufacturers like Ford and Toyota regularly release improved models to keep their products competitive. This cycle of innovation helps extend the product’s lifespan in the market.

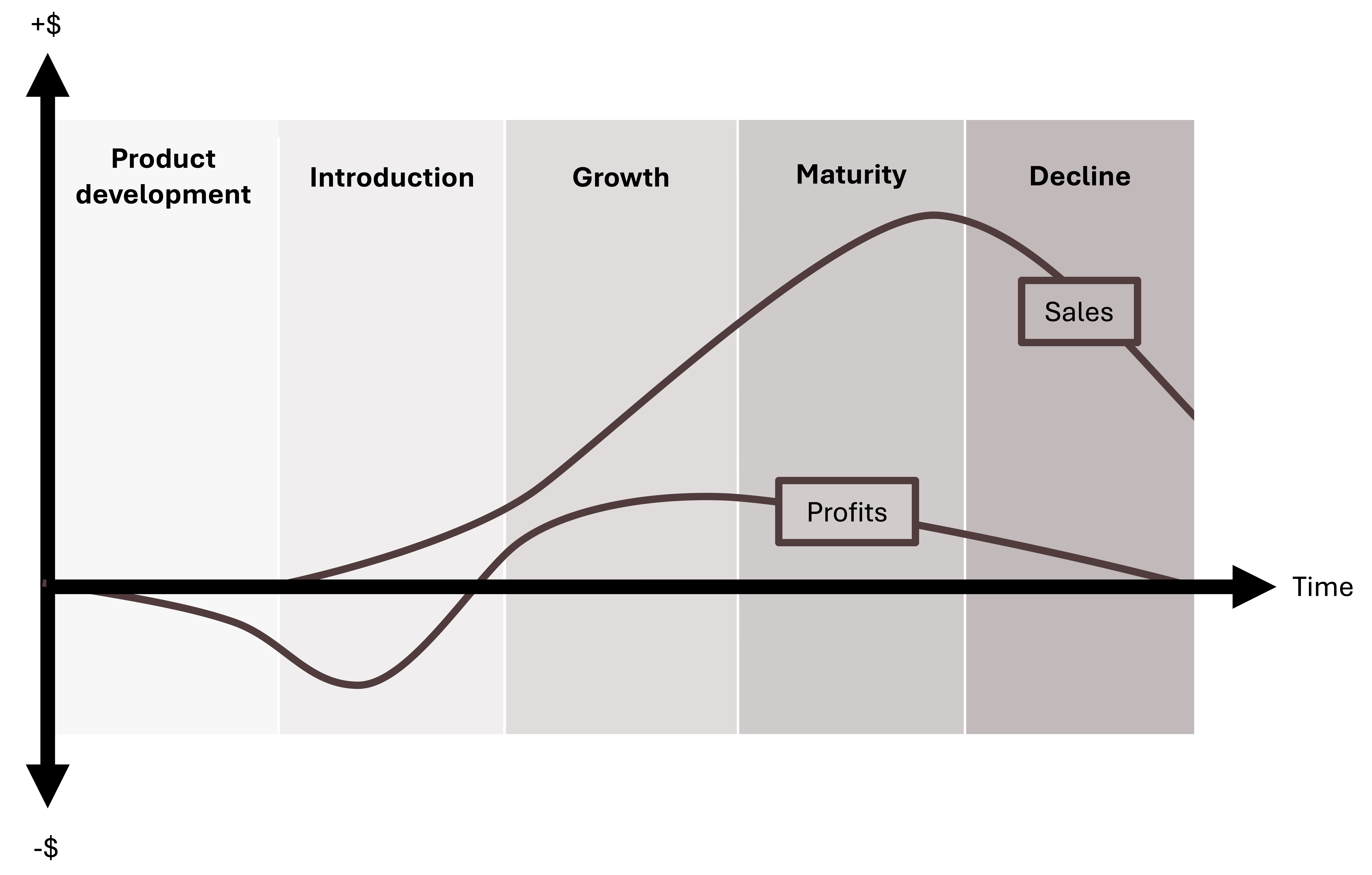

Profits During the Product Life Cycle

Profits throughout a product’s life cycle typically follow a predictable trajectory. In the early research and development (R&D) phase, a company invests heavily in developing the product, resulting in negative profits as costs outweigh revenue. This trend continues into the introduction stage, where sales are still low and significant marketing expenses are required to build awareness, further delaying profitability.

The turning point occurs in the growth stage, where increasing sales allow the firm to start recouping its initial investment in R&D and marketing. Profits usually peak at the beginning of the maturity stage as sales reach their highest levels. However, as competition intensifies during this stage, companies are often forced to lower prices, which erodes profit margins. By the time the product enters the decline stage, profits shrink significantly, and firms may begin looking for ways to exit or consolidate. This pattern highlights the importance of planning throughout the product life cycle to maximize profitability, especially during the growth and early maturity phases when the potential for returns is highest.

Application

- Think about a product you like and use frequently.

- Describe the product’s life cycle.

- What stage is the product in now?

- At what stage did you purchase the product?

When a new product is introduced to the market, it typically follows a progression through four distinct stages that represent the product life cycle. These stages are the same for all types of products, from high-tech gadgets like virtual reality headsets to everyday items like cleaning solutions. Product life cycle stages apply primarily to architectural innovation, radical innovation, and disruptive innovation. The four product life cycle stages are introduction, growth, maturity, and decline. To avoid or delay the decline stage of a product’s life cycle, companies often relaunch their products by introducing updated or improved versions. This is an example of incremental innovation, and it helps revitalize interest and effectively restarts the product life cycle. Profits throughout a product’s life cycle typically follow a predictable trajectory.

9.10 Crossing the Chasm

Now that you have learned about the four stages of a product’s life cycle, how that life cycle can be extended, and profits during a product’s life cycle, you can now learn a closely related idea—crossing the chasm. Crossing the chasm is a concept related to the stages of consumer adoption of a company’s new product or service. It can also apply to industrywide innovations, which are usually technology advancements, such as AI and media streaming services.

The point when a firm’s new product or an industry’s technological advancement crosses the chasm is the point when the success of a new product is more certain. To illustrate this, we review the five stages of a product’s or technology’s adoption life cycle and the related concept of crossing the chasm.

The five stages of a product’s, service’s, or technology’s adoption life cycle include innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. As you can see, the stages of the adoption life cycle correspond to consumer characteristics. These consumer characteristics influence many business aspects of the new product or technology, such as the firm’s marketing approach. Crossing the chasm happens between the early adopters and early majority stages.

Innovators

When a new product, service, or technology is introduced, it is typically adopted first by innovators—people eager to experiment with cutting-edge advancements. These are consumers enthusiastic about the new product, service, or technology. They are typically tuned into the product’s market and may even be eagerly awaiting the next advancement. They may be motivated by the need or want for the new product addresses by the desire to be one of the first to use the new product, or both. Innovators make up about 2.5 percent of the market potential of a product.

Early Adopters

Early adopters are a slightly larger group and follow closely behind innovators. Early adopters show early interest in trying out the product, service, or technology. Early adopters share some characteristics with innovators. These are consumers that are also enthusiastic about the new product or service. Early adopters make up about 13.5 percent of the market potential of a new technology.

Once innovators and early adopters are onboard with a new product or service, about 16 percent of the product’s potential market share is using the new product. This is still a small percentage of the potential for the new product.

Crossing the Chasm

The real challenge for many companies and industries lies in moving beyond these innovators and early adopters and gaining traction with the broader, more mainstream consumer group. This leap to the mainstream is what’s referred to as crossing the chasm, and it often requires a different business and marketing approach to succeed. Innovators and early adopters represent about 16 percent of the overall market.

Early Majority

For the product, service, or technology to become a success, companies must strategize on how to reach the early majority, those customers who represent a larger majority of the market potential for the product. These customers are both enthusiastic about the new product and cautious enough to wait to be sure it is likely to catch on before buying it. They may respond to assurances the new technology is here to stay and is worth their investment. The early majority comprises about 34 percent of the potential market.

Failure to convince the early majority to adopt the product typically leads to the product’s demise. An example of a product that failed to cross the chasm is Google Glass. While it was highly innovative, offering internet-connected eyeglasses that could display information and take photos, its practical value was unclear. Despite generating interest among early adopters, the product did not resonate with the broader market, leading to its failure.

Electric vehicles represent a current example of an industry wide technology in the process of crossing the chasm to mainstream adoption. In recent years, EV adoption has accelerated significantly, with global EV sales accounting for 14 percent of all new car sales in 2023. However, despite this growth, there are still challenges preventing EVs from fully reaching the early majority. Key factors include concerns about charging infrastructure, range anxiety, and the higher upfront costs compared to traditional gas-powered cars. While automakers like Tesla, Ford, and Rivian have made significant strides in addressing these concerns by expanding charging networks and improving battery efficiency, many consumers remain cautious. For EVs to fully cross the chasm into mainstream adoption, these concerns must be further alleviated through more widespread infrastructure, lower costs, and greater education on the long-term benefits of electric vehicles.

As you can see, once early adopters embrace a product, service, or technology, the adoption life cycle peaks at the top of the bell curve. This now represents 50 percent of the potential market. Half the market remains to be attracted to a firm’s product. This is useful information for companies to plan for the next phase in the product life cycle, the late majority.

Late Majority

Consumers in the late majority stage of the adoption cycle of a product, service, or technology are more cautious than early majority adopters. There are many reasons consumers wait to adopt a product, and it is important for a firm to understand their consumer base so that they can tailor their marketing and other business approaches accordingly. The late majority represents 34 percent of the potential market. Once the late majority has joined other consumers in owning the product, the product is used by 84 percent of the potential market.

Laggards

Laggards represent the last group of consumers to come onboard with a new product, service, or technological advancement. Laggards represent the remaining 16 percent of the potential market.

Consumers in all stages of the adoption cycle may belong to their respective groups for multiple reasons ranging from values to affordability. Understanding the specific product adoption cycle of a firm’s products or services or of an industry’s technological advancement is essential to developing approaches that resonate with each group and ensure full market saturation.

Application

- Think about a company with a line of products, such as Apple or Amazon.

- Describe products that have crossed the chasm and ones that did not. Explain your rationale.

Crossing the chasm is a concept related to the stages of consumers’ adoption of new products or services. It can also apply to industrywide innovations. The point when a new product crosses the chasm is the point when its success is more certain. The five stages of a product’s adoption life cycle include innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. The challenge for many companies and industries lies in moving beyond the innovators and early adopters and gaining traction with the broader, more mainstream consumer groups. This leap to the mainstream is what’s referred to as crossing the chasm.

9.11 Cooperative Moves

Bill Gates once noted, “Our success has really been based on partnerships from the very beginning.” In today’s business environment, cooperation between firms is often just as critical as competition. While competition drives innovation and improvement, collaboration allows companies to tackle larger challenges, access new markets, and leverage each other’s strengths. Below, we explore four common cooperative strategies that firms use to enhance their market positions and achieve shared success. Beyond competing head-to-head, businesses can unlock significant advantages by working together.

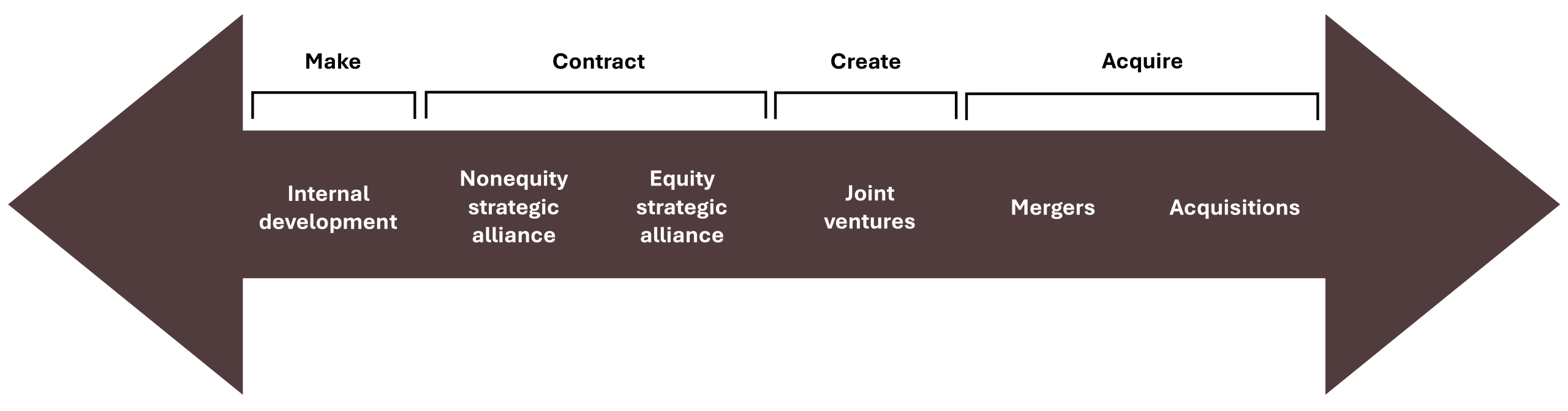

In Chapter 7, we introduced a make-contract-create-acquire continuum to show the ways a firm can diversify. This same framework can be used to cooperate with other firms.

Internal Development

Internal development occurs when firms can choose to build new capabilities and core competencies in-house. This strategy is more competitive than cooperative, as it relies on a firm’s own resources, capabilities, core competencies, entrepreneurial orientation (EO), and innovative culture to drive growth. As previously noted, Apple is an excellent example of a company that relies heavily on internal development.

Internal development taps into intrapreneurship, where employees within the organization use their entrepreneurial skills to create new products or services. Although internal development can take longer and require significant investment, it allows a company to retain full control over its innovations and processes.

Strategic Alliances

Strategic alliances occur when firms partner through an agreement to work together on a specific goal while maintaining their independence.

For example, Starbucks and Spotify formed a strategic alliance to blend coffee culture with music streaming. Through their partnership, Starbucks employees and customers gained access to exclusive playlists on Spotify, and Spotify gained increased visibility through Starbucks’ vast network of stores. Both companies maintained their separate operations, but their collaboration enhanced customer experiences and created mutual benefits.

Another example is the partnership between Nike and Apple, which led to the development of the Nike+iPod activity tracker. This strategic alliance blended Nike’s athletic expertise with Apple’s tech innovation, allowing users to track their workouts using iPods integrated with Nike shoes. It was a win-win for both brands. Nike became more tech-forward, and Apple strengthened its presence in the fitness world without the need for either company to merge or create a new business entity.

The pharmaceutical industry often relies on strategic alliances to drive innovation and growth. For example, Merck and PAREXEL International Corporation formed a strategic alliance to collaborate on biotechnology, specifically focusing on developing biosimilars—pharmaceutical drugs that have properties of other, pre-existing drugs. This alliance is crucial for Merck, as the global biosimilars market is expected to experience substantial growth in the coming years (PRWeb, 2011). Through partnerships like this, pharmaceutical companies can pool resources and expertise, accelerating advancements in medical technologies.

Joint Ventures

A joint venture is when two or more companies combine to create a separate, shared entity. Each partner has a stake in the new venture, involved in everything from decision-making to profits, creating a collaborative relationship with joint responsibility.

Take the collaboration between Google and Fiat Chrysler as an example. The two companies formed a joint venture to develop self-driving cars. Google brought its advanced technology in autonomous driving, while Fiat Chrysler contributed its expertise in vehicle manufacturing. Together, they created a new frontier in the automotive industry that neither could have tackled alone as effectively. By sharing their strengths, both companies could accelerate innovation in the race for autonomous vehicles.

In another scenario, Sony and Ericsson teamed up to form Sony Ericsson, a joint venture aimed at combining Sony’s expertise in consumer electronics with Ericsson’s strong background in telecommunications. The goal was to create cutting-edge mobile phones, which was a market both companies wanted to dominate. Although the joint venture eventually dissolved, during its time, it allowed both companies to compete more effectively against major players in the mobile phone industry.

Collaboration through joint ventures or strategic alliances can open doors to opportunities that might be out of reach if a company tried to go it alone. By pooling resources, knowledge, and expertise, firms can move more quickly and efficiently. However, cooperation isn’t without risks. Companies may face loss of control, potential leaks of confidential information, or even exploitation by their partners (Ketchen et al., 2004).