5 Planning for Instruction

You are a newly hired teacher. You have been asked to examine the sequenced course outline contained in the course of study for the local agriculture program, and select a problem area for which you will develop the written plan for teaching the unit of instruction. You are to include instructional objectives, reasons for studying the unit, questions to be asked, answers to the questions, and approved practices.

The preceding assignment is the first task for all teachers of agriculture. Classroom teaching is the reason for the existence of agriculture teachers. To those of you who read the assignment and felt unprepared to proceed, once this chapter has been read, you will have achieved the ability to complete the assignment.

OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you will be able to

- Develop your rationale for written plans.

- Select a topic and write a plan for teaching it.

- Explain the relationship between planning for instruction, the problem-solving approach to teaching, and techniques of instruction.

- Explain each component of a written plan.

- Complete each component of a written plan.

- Develop daily plans that accomplish the objectives of the unit of instruction.

SELECTING THE UNIT OF INSTRUCTION

Prior to planning lessons, teachers complete the course of study. Included in the course of study are the course offerings for the entire agricultural instruction program (e.g., environmental science, animal science, landscape design and maintenance, and others). For each of these course offerings there is a sequenced course outline. The sequenced course outline contains a list of instructional areas (see Chapter 3) sequenced to the school calendar. Each instructional area contains a list of problem areas for which the teacher will write a unit of instruction. Each unit of instruction contains a list of questions to be answered. Day-by-day learning activities for students are organized around these questions to be answered.

For example (see the feature below), a teacher’s course of study might include the following course offering: Landscape Design and Maintenance. The sequenced course outline for that particular course will include an instructional area called Turfgrass. The teacher would need to develop a written unit of instruction for each problem area (for example, Establishing My Home Lawn). The unit of instruction would then be written to address a number of questions to be answered such as, “How do I test the soil?” Later in the year the teacher will write another unit of instruction to teach the problem area, “Maintaining My Home Lawn.”

| Landscape design and maintenance—Course outline | |

|---|---|

| Course title: (from course of study) |

Landscape Design and Maintenance |

| Instructional area: (from sequenced course outline) |

Turfgrass |

| Problem area: (for which the unit of instruction is planned) |

Establishing My Home Lawn |

| Questions to be answered: (from written unit of instruction) |

• How do I test the soil? • How do I prepare the seedbed? • What equipment do I need to sow grass seed? • How do I sow the grass seed? • How do I mulch and water to establish the grass? |

| Problem area: (for which the unit of instruction is planned) |

Maintaining My Home Lawn |

| Questions to be answered: (from written unit of instruction) |

• How do I properly mow the lawn? • What fertilizer should I use? • What are the recommended watering rates? • How do I control for diseases? • What insects and pests are common? • How are insects and pests controlled? • How do I control weeds in my lawn? |

When planning the course of study from which the preceding example was taken, the teacher included a problem area or unit of instruction titled, “Establishing My Home Lawn.” At the time the course of study, including the sequenced course outline for each course offering, was developed the teacher had little more in mind than the basic instructional areas and problem areas that were listed. Now the teacher needs to take a problem area and decide on the list of questions that must be answered before students fully grasp the content. The teacher develops a plan for helping students find answers to the questions. In doing this, the teacher begins the necessary preparation for successful classroom teaching.

The teacher begins with the title of the unit of instruction, which restates the problem area, “Establishing My Home Lawn.” This title, this basic idea or general notion, then has to be developed. A content outline must be brainstormed. This structuring, or filling-out of details, is included in the planning of the unit of instruction, and is often referred to as lesson planning.

Not only do teachers need to decide on specific content to be taught as a part of each unit of instruction but they also must plan for ways to teach so that students master the subject matter in the problem area. This requires serious contemplation. Subject matter as well as pedagogy must be selected and sequenced. Without prior thought (planning), optimum teaching effectiveness is seldom achieved. Yet some teachers resist the disciplined effort such planning requires and quite often ask if plans need to be in writing.

RATIONALE AND NEED FOR WRITTEN PLANS

Remember the principle of learning, “When the subject matter to be learned possesses meaning, organization, and structure that is clear to students, learning proceeds rapidly and is retained longer.” This is the heart of developing written plans. Through written plans, the teacher is bound to develop sensible and complete organization and structure that can be made clear to students. Otherwise, organization is fragmented and the structure of the subject matter and learning experiences is much more imperfect.

Efficiency is gained by recording the planning before teaching a problem area. Less time is spent rethinking, and the plan can be used for subsequent classes.

The act of writing out a plan forces the teacher to process the subject matter. When teachers think through a concept thoroughly enough to figure out how best to make it clear to others, they understand it better and are able to teach it with greater authority and clarity.

By taking time to write down the plan for teaching, the teacher is more likely to be able to draw on and make use of more of the principles of learning. A teacher is also apt to do a better job of properly selecting and using a variety of techniques of teaching.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PLANNING FOR INSTRUCTION AND THE PROBLEM-SOLVING APPROACH TO TEACHING

When teachers encounter a need to plan a new unit of instruction, they encounter problems in two ways. First is the problem of planning a unit of instruction. Second is the need to solve the problem or problems they intend to teach their students. In managing both of these kinds of problems, teachers can make use of the very kind of problem solving the authors are advocating.

When you as the teacher determine the solution to the problem to be taught, and when you develop a plan for teaching the solution, you encounter the same felt need to know that you are always trying to impress on your students. The next step is to clearly define the problem; how can you best plan this unit of instruction, and what is the solution to this “question to be answered?” After clearly defining the problem, you gather the information that is pertinent to the “question to be answered” that is being taught. You then need to develop the best possible answers and apply them in planning instruction. As the unit is taught, as well as after it is completed, you need to evaluate the effectiveness of the plan. In following the steps that were just identified, you have followed the same steps of problem solving through which students will be guided in their instruction.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PLANNING FOR INSTRUCTION AND TECHNIQUES OF TEACHING

Techniques of teaching are presented in Chapters 6 and 7. They represent the tools that teachers use either to present information or to guide students in their discovery of knowledge. Techniques of teaching are used in problem-solving teaching during the data-gathering step. They are also used to create interest and to develop the discussion needed to lead the class in constructing lists of reasons for studying the unit and questions to be answered.

First, you need to understand the overall scheme of the planning phase. Then you need to study and learn how to use each of the teaching techniques presented in Chapters 6 and 7. Not until you have mastered both the planning process and the techniques of teaching will you be able to effectively plan and present instruction in the classroom and laboratory.

Consider the following assignment. If it was actually your assignment to complete, would you be able to complete it satisfactorily?

Prepare to instruct students on “Establishing My Home Lawn.” Outline the parts that must be included, and complete each part so that you can teach the problem area in a masterful fashion.

In order to meet this challenge, what must you know and be able to do?

This is the task that teachers face when they develop written plans for the unit of instruction. The written plans for the unit of instruction include the following parts:

Outline of Unit of Instruction

- Title

- Situation

- Instructional objectives

- Interest approach

- Reasons for studying the unit

- Questions to be answered

- Answering questions, acquiring knowledge, and developing skills

- Application of learning

- References and teaching aids

- Evaluation procedures

In order to understand how to plan using this approach, each step in the plan is explained and illustrated with an example. The sample unit of instruction will be “Establishing My Home Lawn.”

TITLE

The title for the unit of instruction should be stated in action terms to convey to the students that this is a unit in which they will be involved. Action can be denoted in the title by using the ing ending, such as calibrating, timing, constructing, selecting, or designing. Another way of putting action into the title for the unit of instruction is to use a “how to” title such as “how to castrate pigs,” “how to provide low-voltage outdoor lighting,” or “how to feed cattle.”

The title of the unit of instruction should accurately describe what the unit is about and should provide at least a preliminary idea of the scope of the unit. It should also follow the filing system the teacher uses to file plans as well as the pattern of organization used in the students’ agricultural education notebooks.

Consider the example being used for illustrative purposes in this chapter, “Establishing My Home Lawn.” This title conveys a sense of “we’ll be establishing a lawn,” which implies activity, involvement, and decision making on the part of the learner. Such a title enables the teacher to file the plan under the teacher’s notes that deal with turfgrass, and the students can be told to place their notes and handouts for this unit of study under whichever section of their notebook the teacher selects, such as agronomy.

SITUATION

Before teachers of agriculture begin planning a unit of instruction, they need to think about the local situation in which the unit will be taught. Teachers do not plan to teach information for information’s sake; rather, they plan to teach what is relevant to the students’ specific situations and needs. In the case of the unit “Establishing My Home Lawn,” it is important for the teacher to reflect on the specifics of the community, the students in the class, and the specific home lawn(s) that will be established as a part of the laboratory activities that are included in the unit of instruction (see Case 5-1) and as part of a student’s home improvement SAE or entrepreneurship SAE. That which is taught will be learned with reference to specific situations in which students find themselves.

The situation forms a frame of reference within which the unit is taught. By writing down the situation, instructors force themselves to keep their instruction relevant and specifically focused on local needs. After teaching for awhile, teachers are so familiar with the local situation they do not have to write it down, but they still start their planning process by considering it. This situational information becomes the foundation of the plan. It provides the basis for identifying content via a list of problems and concerns. The situation should describe pertinent agricultural practices in this community as they relate to this particular unit of instruction. One would include information on the scope of the problem area, practices that are currently being used, problems that have been observed in the community, experiences each student has had in this area of instruction, and any other community-related information that needs to be considered as a teacher plans instruction.

It is also appropriate in the situation to include all state proficiency skills or competencies that are required to be taught in agricultural education, and all math and science standards, and state career or technical education standards that need to be met through the agricultural education curriculum. Case 5-1 provides an example of that which should be addressed in the situation section of a unit of instruction.

Case 5-1: Situation

- The class has not studied establishing home lawns previously.

- Three of the twenty-one students have helped establish a home lawn previously.

- The class is to establish, as a laboratory project, a home lawn for Mr. Dobson.

- Most homeowners in the area fail to get their seedbed fine enough to cover the seed properly or to use the best variety of grass for their conditions and intended use.

- Five of the students will have jobs with lawn care services this summer.

- Three of the students wish to start their own lawn establishment, renovation, and care businesses.

- Several new housing developers are in need of people to establish new lawns from seed.

- Three of the students will have SAE improvement projects on improving the home lawn.

- One of the students in the class is working toward an FFA Turfgrass Management Proficiency Award.

In order to effectively delineate the pertinent information for the situation, teachers have to consider a number of sources, such as home or supervised agricultural education visits, awareness of current practices used and problems encountered, agricultural census information, and data from students’ record books (such as average yields, profits, hours worked, and rates of gain).

Once the situation is developed, it not only serves as a backdrop against which planning is conducted but it can also serve other purposes. Specific problems observed can become the basis for creating a desire to study the unit. Production data can be used to create interest also. For example, a teacher could point out to the class that the average corn yield in the state is 147 bushels per acre; in the county it is 121 bushels per acre. The best young farmers average 137 bushels per acre, and the class average last year was 100 bushels per acre. This situation data is provocative and stimulates interest in the problem area. The process of developing the situation also reveals specific problems to be indicated under the “questions to be answered” section. With the situation clearly in mind, the teacher is ready to develop specific instructional objectives for the unit of instruction.

INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES

Prior to teaching a unit of instruction or even planning for teaching a unit, it is essential that teachers decide what they want their students to know and be able to do once the instruction has been provided. The goal has to be defined and developed before the teacher can achieve it or even determine how to achieve it. The teacher’s statements of intended learning outcomes are called instructional objectives. It is important to remember that these are the teacher’s goals for the unit of instruction. This is what the teacher wants to achieve from the unit.

Why Are Objectives Needed?

In writing instructional objectives, teachers make definite decisions about the content of the problem area. They force themselves to establish parameters that in turn help define and limit the scope and content of the problem area. Objectives also help teachers decide what is truly relevant and worthy of students’ learning versus that which is “nice to know.”

Instructional objectives also help teachers begin to make decisions about the sequence of instruction. As objectives are developed, teachers begin to realize what knowledge and skills need to be learned and in what order. A final reason for writing instructional objectives is that they provide a basis for evaluation. If teachers decide in advance that they want students to know and be able to do certain things, share those expectations with students, and plan their instruction so as to accomplish those objectives, then it only makes sense to evaluate success (of student and teacher) based on the instructional objectives with which they began.

Case 5-2: What is the objective?

The following is your assignment. Leave where you are now and without using any map or talking to anyone, drive to Chase City. When you get there, call the following number, and you will receive further directions: 777-888-9999. Some questions:

- How likely will you be to reach your assigned destination?

- How can you plan to get there with the most efficiency?

- How will you know when you have reached your intended goal?

Analysis of Case 5-2. Read Case 5-2. Chances are a person would have very little success completing the assignment. It’s very difficult to plan a journey if you don’t know where you are headed and have no mileposts to guide you; and so it is with planning instruction. If teachers do not know where they wish to go or how to get there, then the resulting instruction is apt to be haphazard, confusing, and unproductive. Yet, many teachers try to begin planning instruction before they take time to adequately decide what they hope to accomplish.

Domains of Learning

Objectives or desired learning outcomes fall into three domains of learning: cognitive, psychomotor, and affective.

Cognitive behavior or outcomes deal with the acquisition of facts, knowledge, information, or concepts. Psychomotor behaviors are in the realm of manipulative skills—using the mind in combination with motor skills. These are prominent outcomes of agricultural instruction. The psychomotor domain is the whole area of “hands-on”—actual performance of skills. Psychomotor learning is not accomplished without appropriate cognitive understanding. Affective behaviors have to do with attitudes, values, aesthetics, and appreciation. This is the most difficult area to have reflected in the list of teacher objectives. However, the affective area is a crucial domain of learning that agriculture teachers wish to stress.

In the list of objectives presented in Case 5-3, which objectives do you believe are addressing the cognitive domain, which the psychomotor, and which the affective? Objectives 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, and 9 address the cognitive domain. Objectives 6 and 7 address the psychomotor domain. None of the objectives are written to address the affective domain. An example of an objective written for the affective domain might be, “To appreciate the beauty of a well established home lawn.”

Writing Instructional Objectives

The most important characteristic of an instructional objective is that it clearly and completely communicates to the teacher and students what it is the students should know and be able to do on completion of the unit of instruction. The major focus of instructional objectives should be on specifying observable (measurable) behaviors that students need to exhibit once they have studied the problem area. These behaviors are called the performance.

When writing the objectives, teachers should use verbs that are action oriented. Examples include explain, describe, select, compare and contrast, recommend, identify, and prescribe. The key idea is that the verb should specify a behavior of the student that can be observed and measured so that the teacher can determine whether the instructional objective has been met and to what extent it has been met. Keep in mind that these action, measurable verbs also fulfill cognitive requirements. For example, “to explain” requires a higher level of cognitive activity for the student than “to list.” See Appendix B for guidance on selecting verbs that challenge students to think across all cognitive levels.

Many writers insist that instructional objectives also specify the conditions under which the student’s behavior will be measured and the criteria that the student’s performance must meet. Certainly, teachers must decide on these things if they are to be able to adequately determine whether an objective has been met. Thus, a completely written objective contains three parts: (a) the behavior, (b) the conditions under which the behavior is to occur, and (c) the criteria by which the performance is judged. Consider the following objective as an example.

Given an E6014 electrode, the learner is to weld a stringer bead such that the width of the bead is 2.5 times the diameter of the bare end of the electrode and the height is 1.5 times the diameter of the bare end of the electrode.

The measurable behavior (performance) is indicated by “weld a stringer bead,” with “weld” being the action verb. The condition under which the behavior will be measured is indicated by the words “Given an E6014 electrode.” The criteria are indicated by the words “such that the width of the bead is 2.5 times the diameter of the bare end of the electrode and the height is 1.5 times the diameter of the bare end of the electrode.” Hence, the sample objective contains all three parts.

The minimum that teachers should include in their written instructional objectives is the performance or observable behavior. For the sample plan on “Establishing My Home Lawn,” the instructional objectives in Case 5-3 are appropriate.

Relationship of Objectives to Content to Be Taught

It should be apparent that the list of instructional objectives is parallel to the subject matter content of the unit of instruction being planned. In essence, the objectives identify the major knowledge, skills, and values that are to be taught. It is from this list of major ideas to be addressed that the rest of planning flows. In fact, when teachers plan their list of questions to be answered, the questions to be answered will parallel the list of instructional objectives.

Case 5-3: Instructional objectives*

The learner will be able to

- Interpret soil test data and apply the correct amount of fertilizer or lime to a given lawn site.

- List the steps to follow in properly preparing a seedbed for a home lawn.

- Select the appropriate variety of seed for various home lawn situations.

- Develop a list of tools (and their costs) that are needed to sow seed.

- Compare the advantages and disadvantages of the methods of seeding lawns that were taught in class.

- Demonstrate ability to use the seeding techniques taught in class.

- Apply the appropriate mulch to cover the seed.

- Explain why mulches are needed.

- Solve problems for giving estimates on establishing home lawns.

*Notice that these objectives specify only the performance. It is assumed that in delineating the performance the teacher has in mind, the conditions under which the performance will occur and the criteria it must meet will have to be considered.

Finally, then, it is the list of instructional objectives that indicates to the teacher what the evaluation should include and should stress as major points in the content being taught.

INTEREST APPROACH

Teachers need to have the basic aims of the interest approach, as presented in Chapter 4, in mind when they plan the interest approach for their problem area. They must also remember the principles of learning on which motivation and interest rest (see Chapter 2).

Sources of Interest Approaches

Teachers need to constantly look for good ideas for interest approaches—ideas that will create a desire in students to know more about a topic. Lessons should not simply be funny, sensational, or dramatic; rather, the study should begin in a way that causes learners to be interested in overcoming inabilities and solving real problems that affect them as individuals.

True felt needs and provocative situations grow out of personal situations students face. Hence, teachers can develop many good interest approaches based on the students’ supervised agricultural experiences. These include production projects, improvement projects, research projects, entrepreneurship projects, projects in business or on another persons’ farm, and school laboratory projects. By clearly portraying the specifics related to students’ experiences and programs, genuine desires for knowledge can be generated. For example, if a group of students who are enrolled in small animal care knew they had three dogs to groom in lab and they didn’t know how to proceed, then they would easily recognize a “need to know.” Likewise, if several students have sows about to farrow and, when engaged in a class discussion, they are not sure how to best care for the sow at farrowing, then they are apt to “want to know” more. The teacher needs to become committed to learning how to apply the unit of instruction to students’ situations.

Another good source of interest approaches is the use of case studies or case problems. Teachers can develop fictitious letters from agriculturalists that ask for advice or request that the members of the class complete a project the agriculturalists do not know how to complete—but should be able to complete—or give descriptions of common dilemmas faced by people in the occupational area and ask students what course of action needs to be taken.

Experiments are an excellent source of interest approaches. The teacher could bring in two containers, one with corn seed planted one and a half inches deep, another with corn planted three and a half inches deep, and raise thought-provoking questions as to which would do better and why. The students can then write hypothesis statements about the potential outcome of the experiment. When studying nutrition, students could write hypothesis statements, then begin feeding two groups of baby chicks two different feeds to test diets. The class would then study the problem area in class to find out how and why diets matter.

Demonstrations are also a good way to generate interest. The teacher could begin a unit of study on fish hatcheries by expertly removing the eggs from the female and then turning to several students to see if they can do the same. If they lacked the necessary knowledge and skill, they would immediately realize it and admit that they needed to know more.

Another way of creating interest is to plan a series of puzzling questions. Get students to commit themselves to an answer and then pursue the question—why? When students conclude they are not sure, then the teacher is ready to move them to the point where they realize it is important that they learn more.

Whatever the source or manner of creating interest, it is essential that the teacher plan the scenario in writing.

What to Write Down

For the interest approach and all other parts of the unit of instruction, there are two categories of information that teachers need to write down. One is a set of directions that the teacher writes to himself or herself, the other is the key content.

Directions to self, at a glance, tell the teacher what to do and the order in which to do it. These are thought-out directives that are purposely ordered to achieve the desired effect. They include statements such as, “Show the transparency on average yields,” “Distribute Mr. Leuellen’s letter,” “Have the class suggest specific reasons why an engine will not start,” or “Ask the following questions: (a) When do we need to start lilies if we want them to be ready for Easter? (b) How should they be planted? (c) What fertilization program is needed?”

Examine Case 5-4, which is an example written plan for an interest approach. The written plan is divided into two columns with directions to self written in the left column and key content written in the right column. Directions to self include “Distribute,” “Show Transparency 1. How much should we charge for the job?” “Ask,” and “Probe.” Key content includes Dr. Dohson’s letter, and the lead question. Separating the directions to self from the key content allows the teacher to think through and write the key content in a logical flow in the right column without the intrusion of the directions for how it will be done. The teacher then, likewise, thinks through and plans for the logical flow of the classroom processes by examining the directions to self in the left column. Also, by separating the directions to self from the key content, the teacher can very quickly glance at the plan, even from a distance (i.e., from the blackboard to the podium that is holding the plan) and see that the next direction to self indicates, “Transparency 1” in the left column. The teacher sees where he or she is headed with the lesson, and subsequently begins, mentally and physically, to move in that direction.

Case 5-4: Interest approach

| Directions to self | Key content |

|---|---|

| Distribute the attached letter to the class. | Letter from Mr. Dobson: Dear ______: I would like to request your class to put in a new lawn at my home which is currently being built. The area to be seeded is 1/2 acre. I will pay you for the job. Please advise me of your decision and give me an estimate of cost if you are willing to accept the job. |

| Show Transparency 1. "How much should we charge for the job?" | |

| Ask students to develop a list of tools and supplies we would need if we took the job. | |

| Probe: When the class as a whole begins to experience problems answering the questions (because they need to know more before they can respond), probe as to whether they want to take on the job (anticipated answer is "Yes"). | |

| Ask students | "Why is it important for us to know how to establish a new lawn?" (This question provides the transition to the next phase of the problem-solving approach.) |

The other category of information that must be written down as a part of the plan is key content. Key content may include facts and figures. It may be key notes presented on the board or on an overhead, or a handout. It may be the key ideas of a case situation or a real situation faced by a student in the class. Whatever it is, enough must be recorded in writing such that at a glance it is clear and complete enough for the teacher so that he or she can fluently develop a high level of interest in the students for studying the unit. Consider Case 5-4.

Analysis of Case 5-4. First, look at what was recorded in the teacher’s plan. The key content for this interest approach is the letter from Mr. Dobson (written in the right column). The directions to the teacher (written in the left column) include comments given before and after the letter. These directions are sequenced so as to gain commitment from the learners and then give the class specific assignments that they will want to complete but cannot without additional information and skill. These directions lead the class to a closing point where they conclude that they need to know more and agree it is worth learning.

The techniques the teacher uses deal primarily with offering the students an experience as a class that they would like to have, and then helping them understand that their lack of knowledge and skill prevents them from having the experience. This is an actual group situation that personally affects all class members and thus provides an actual felt need for the entire class. Individual student situations (creating home lawns) could have also been used to create this felt need if they were available. The teacher then makes use of probing questions to help the students discover and admit their need for further study.

The final phase of the interest approach involves planning for closure and transition to the next step—establishing reasons for studying the unit. Teachers must remember that the interest approach should be designed as a logical way of beginning study in an area—it is not a free-standing part of a unit of instruction. In addition, it is not a feature that is unrelated or unconnected to the next step in the learning process. The interest approach must be planned and carried out such that it makes its point clearly and leads students to conclude that they do not have all of the answers they need to have.

Once planning for closure is accomplished, the teacher needs to plan a transition into reasons for studying the unit. Remember that the purpose of the interest approach is to get the students to decide they need to know what is about to be taught; the purpose of the “reasons for studying the unit” is to get the students to discover why they need to know what is being studied. So, the interest approach ends with this transition comment, “But, why do we need to learn this?”

The teacher then needs to plan some bridging comments that link the content of the interest approach with a class discussion that reveals why students want to study the unit of instruction. It can be considered to be a connecting part of the lesson plan. In essence, the teacher has to deliver the following message, “OK, you say it’s important to learn how to … (whatever the problem area that is being introduced). Help me understand why this is important.”

REASONS FOR STUDYING THE UNIT

Two facets of planning are needed for establishing the reasons for studying a unit at the beginning of the unit of instruction. Because establishing reasons for studying the unit reveals students’ objectives and goals, the teacher has to lead students into discovering and verbalizing why they believe it is important. The best way to accomplish this is to develop several leading questions that, when asked, will cause students to think of their reasons for wanting to learn that which is about to be taught. The following lead questions will serve this purpose well.

Some Lead Questions for Establishing Reasons for Studying This Unit

- Why do you need to learn how to (whatever the problem area is)?

- What are some goals you wish to achieve by learning how to (whatever the problem area is)?

- What are some objectives you hope to accomplish through studying (whatever the problem area is)?

- Why is it important to learn how to (whatever the problem area is)?

Next, the teacher should record in the plan some possible responses students are likely to give. The primary reason for recording several likely responses is to have some “hints” written on paper in front of you in case students have difficulty thinking of reasons for studying the unit of instruction. It is important to remember that these possible responses are simply extra ammunition for the teacher that can be used to generate discussion if and when needed. Students do not need to give the same responses or any of the possible responses that are recorded on the teacher’s plan. To force them to give the teacher’s anticipated responses would remove the psychological leverage this portion of the plan is meant to provide. Examine Case 5-5, Reasons for Studying This Unit.

Case 5-5: Reasons for studying this unit

Lead questions:

- What are some reasons you believe you need to learn how to establish a home lawn?

- What are some goals you should strive to accomplish in learning how to establish a home lawn?

Possible reasons students want to study this problem area:

- To do a good job on Mr. Dobson’s lawn for the laboratory project.

- To learn enough to start a personal lawn service.

- To get out of the classroom and work outdoors.

- To be able to re-establish my own lawn for my supervised experience improvement project.

Analysis of Case 5-5. Notice that two lead questions were recorded. Their purpose is to prompt students to think of reasons they believe they need to learn how to establish a home lawn. Always give students the chance to individually write on paper at least one reason of their own before opening the verbal exchange in the class. This way students are given time to think, and especially to think independently, before the class discussion proceeds. In case no one offers a reason, the plan contains some plausible reasons students might suggest. If no student suggests a reason for studying the unit, the teacher could ask if one of the reasons listed on the teacher’s plan was a viable reason. If so, it would be recorded on the board, and then the teacher would encourage class members to add one, two, or three other reasons that they would think of on their own.

QUESTIONS TO BE ANSWERED (PROBLEMS TO BE SOLVED)

Before examining the specific aspects of planning involved in this section of the unit of instruction, the reader needs to distinguish between problems and questions. Real problems are “questions that must be answered” in order to remove a felt need that personally affects the learner. When the data gathering is related to a personal concern, then one is dealing with a problem. If a student’s cow has bloat and he or she wants to know how to treat the cow for bloat, that is a real problem. If a student is interested in cattle and would like to know how to treat cows for bloat, this is a question. Thus, what is a problem for some students is a question for others. The more often your teaching can use real problems that actually affect one or more members of the class, the more exciting the study will be.

When students study questions, they could be seeking information for information’s sake. With problems, students have a different frame of reference. They are seeking information in order to remove a problem that personally affects one or more of them.

Questions to be answered are the core of the problem area in the problem-solving approach to teaching. They lead to the specific content and final practice that the problem area is designed to produce.

By thinking of the questions to be answered (problems to be solved) before addressing specific content to be taught, the teacher, when planning, is forced to consider the entire problem area and think it completely through. This section of the plan provides a framework for reasoning. Then when the students are led through this step of the plan as the problem area is presented, they too are forced to think through (or reason through) the entire area of study.

The questions to be answered also provide the framework for the problem area being studied. The questions define the subject matter to be taught. They provide a way of organizing teaching and hence learning. Additionally, the list of questions to be answered provides guidance, direction, and structure.

Identifying Questions to Be Answered

In order to clearly and completely identify the best questions to be answered for a unit of instruction, teachers of agriculture should begin by focusing on the title of the problem area and deciding what questions logically need answering. Then the teacher should reason through all the questions related to the topic. Sometimes it is helpful to mentally review the process to which the unit of instruction refers, the task to be completed, or the information to be gained in order to be sure the list of questions generated by the students is complete. In doing this, the teacher may reflect on personal experiences and consider his or her own expertise and skill in the area. Also, by comparing the list of questions to the list of teaching objectives, the teacher can usually detect any omissions.

Additionally, the list of questions to be answered grows out of the situation for which the problem area is being studied and will reveal the important problems and questions that must be studied. Be careful not to try to pull your words from the students, or to try to pull your complete list from them. Instead, use the students’ words, knowing that what they mean parallels what you anticipated they would say. You also will add to their list the items that you had planned to study that they have not verbalized.

Once the total list of questions to be answered has been identified, the teacher then needs to carefully sequence the list. The list of questions needs to be arranged in a sensible order, with questions of a prerequisite nature addressed before those for which they are prerequisite. Thus, by answering the first question (or solving the first problem), the class is better prepared to study the next one. The learning from studying each question builds cumulatively.

Planning for Developing the List of Questions

The same approach is used for planning this section of the unit of instruction as was used to plan the reasons for studying this unit section. First the teacher identifies and records a list of lead questions designed to help the learners think of the “questions to be answered” that require study before they can solve the problem with which the unit of instruction deals, and before they can address the reasons for studying this unit that they have identified.

Some Lead Questions for Developing a List of Questions to Be Answered

- What are some questions you will need to answer before you can (whatever the problem area is about) or reach your objectives?

- What are some things you need to know and be able to do in order to (whatever the problem area is about) or reach your objectives?

- What are some problems you have to solve in order to be able to (whatever the problem area is about)?

Case 5-6: Questions to be answered

Lead questions:

- What are some questions you must answer before you can satisfactorily establish a home lawn?

- Give me some problems you think we need to solve before we start on Mr. Dobson’s lawn or as we work on it.

- What are some things we must be able to do if we are to do a good job of establishing lawns?

Anticipated questions the class should identify:

- When should we establish a home lawn?

- How do we get the ground ready for planting?

- What kind of grass should we plant and at what rate?

- What fertilizer should we use and how much should we use?

- How do we plant the seeds?

- What do we do after we have sown the seeds?

- How do we know how much to charge for the job?

Analysis of Case 5-6. Teachers can be certain that when they lead the class in developing this list of questions to be answered, it will not be a perfect match to the list the teacher has written in the plan. Thus, a teacher must be sure the list in the plan is complete. The teacher, as the expert, must ensure that all appropriate questions are included in the list to be studied for the unit. If the students are not able to think of all the questions, the teacher must finish the list for the class. The list generated in class should then be reviewed with the class to establish a clear order, combine questions that are too fragmented, and summarize this important overview to the unit of instruction.

By leading the class in reviewing and ordering the list of questions to be answered developed in class, the teacher helps the students gain practice at revising their first thinking. They learn to group similar concerns to gain greater efficiency. They also learn to logically order their inquiry to facilitate greater understanding.

The important benefit to the teacher is that the class list of problems and questions then is more nearly matched with the order the teacher has followed in developing the plan for instruction.

ANSWERING QUESTIONS (SOLVING PROBLEMS), ACQUIRING KNOWLEDGE, AND DEVELOPING SKILLS

The planning for how to help students solve problems, acquire needed knowledge, and develop new skills is the very heart of the process of planning instruction. As teachers determine how best to teach students in any problem area, they have to simultaneously consider the specific knowledge, skill, practices, and principles that will be taught. A crucial part of planning instruction is identifying and selecting content.

Teachers need to assess their own knowledge, complete additional background study, and visit with practitioners to be sure they have identified what students need to learn in order to solve the problems being studied. To become fully acquainted with subject matter to be presented, teachers must review sources of information and teaching materials, such as books, pamphlets, Internet sites, CD-ROMs, DVDs, visual aids, experiment station bulletins, and extension publications.

As teachers identify and select content, subject matter, key points, practices, and principles, they concomitantly begin to make at least preliminary decisions about how they might best be able to help students learn what they need to know in order to solve current and future problems. As content and potential methods are brought into focus, teachers then move on to planning specific solutions to each of the questions to be answered in the unit of instruction.

Planning for Solving Problems, Acquiring Knowledge, and Developing Skills

The first planning activity for each question to be answered is a trial discussion. This requires developing, on paper, a strategy for completing a trial discussion. It may consist of jotting down several questions that will be used to re-create interest, create a division of opinion, determine existing levels of student knowledge about the question, or helping students realize that a more thorough period of study is needed. This part of the plan must also indicate to the teacher how to smoothly move into presenting the final solution of the problem.

As teachers plan trial solutions as well as actual solutions to each problem, they will need to select techniques of teaching that are appropriate for the given situation. These techniques are thoroughly explained in Chapters 6 and 7.

In planning for the detailed teaching (and learning) that must follow the trial discussion, two fundamental elements must be included in the written plan: directions to self and key content.

- Directions to self present instructions or guidelines in sequential order (this is the information recorded in the left column of the written plan).

- Key content (concepts, principles, practices, and facts) that must be learned in the process of studying the problem as presented (this is the information recorded in the right column of the written plan).

Each element is discussed in detail.

Directions to Self. Directions to self are not simply a matter of teachers writing scripts for themselves. Rather, teachers need to list some catchy phrases that can be read and comprehended at a glance (noted in the left column of the written plan). This portion of the teacher’s plan is a guide to the orchestration of the teaching episode. Consider the accompanying chart of directions to self and key content.

Consider the following examples of the kinds of directions that are needed.

| Directions to self | Key content |

|---|---|

| 1. Show Transparency 7. | (This key content is printed on the transparency.) |

| 2. Discuss the following points: | 1. Remove all dead and diseased wood 2. Remove all crossed branches 3. Create desired form |

| 3. Demonstrate the procedure to follow: | see attached notes (notes regarding the procedure are found in the supporting materials attached at the end of the unit of instruction).

Steps: |

Notice that in direction 3 (“Demonstrate … “), additional notes are referenced. It would be in these notes that the details of the key content (facts, figures, key points) are recorded. Likewise, in direction 2 (“Discuss … “), the list of points (noted in the main body of the teacher’s directions to self) contains the specifics to be presented or otherwise learned. As was discussed earlier, most teachers are successful if they keep their subject matter notes (key content) separated from their pedagogical directions (directions to self).

Key Content. In the case of the key content of the planned solution, it is crucial that the subject matter recorded is clear, precise, and thorough. It may be recorded in the form of notes to be put on the writing surface or transparencies to be presented, slides, a detailed demonstration, study questions, conclusions for a supervised study period, or any number of techniques discussed in Chapters 6 and 7. The crucial point is that if instruction is to be clear and thorough, the key content must be written in the plan.

Following are examples of ways in which key content is recorded in the left column of the written plan:

Example 1: Using a transparency to record key content

| Directions to self | Key content |

|---|---|

| Show Transparency 2: Guidelines to follow in transplanting seedlings | (This key content to be taught is printed on the transparency, "Guidelines to Follow in Transplanting Seedlings.") 1. Transplant as soon as the seedlings show the first true leaves. 2. Transplant into containers in which they will be sold. 3. Make holes in soil to receive one seedling per hole: a. Dibbles i. Single ii. Board with several |

| Show slides 12-16 | (The key content to be taught is printed on the slides.) b. Mechanized methods (slides 12-16 illustrate each type) (and so forth) |

Example 2: Using notes to yourself of technical details to record key content

| Directions to self | Key content |

|---|---|

| Blackboard: Soilless mixes | Notes for question 3 in unit of instruction Types of soilless mixes— 1. Jiffy-mix 2. Redi-earth 3. Metro-mix 4. Pro-mix 5. Ball-mix |

| Show: Samples of each as each type is written on the board |

Example 3: Using attached copies from specific resources to record key content

| Directions to self | Key content |

|---|---|

| Blackboard: List the parts of the ignition system. | (Full list on page 10 of Briggs and Stratton; copied and attached.) |

| Describe the function of each part. | (Chapter 2 in Briggs and Stratton; copied and attached.) |

Case 5-7: Problem 5: How to plant the seeds

| Directions to self | Key content |

|---|---|

| Bring in small box of seed that can be shaken out of top for spot seeding. Bring in large bag of seed. |

Notes for question 5 in unit of instruction |

| (Trial discussion) Ask a student to come forward and show the class how to spread the seed for best results-we want 3 lbs per 1,000 sq ft. (Note: If there is clear division of opinion and lack of understanding, the trial discussion ends, so move on into remainder of solution.) |

|

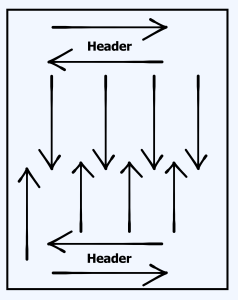

| Show Transparency 2: What is the recommended way to apply seed? | "What is the recommended way to apply seed?" a. Use drop-type spreader. b. Follow length of lawn. c. First apply two header strips. d. Then go back and forth. e. Shut off spreader gradually as you approach header strips. f. Overlap wheel tracks for even coverage g. May prefer to sow twice at lowest recommended rate-with second seeding done at a 90-degree angle to first. |

Blackboard: Draw sketch of seeding method |

|

| Discuss seeding | How deep should seed be covered? Answer: 0.1-0.3 inch with soil |

| Discuss tools | What tools are needed? Tools: bamboo or leaf rake |

| Demonstrate tool use | How are the tools used? Use back side, apply light pressure |

| Supervised study: Students use the publications | Lawn Care (Scotts page 255) and Lawn Establishment (Extension Publication# H-1011 ). |

| Blackboard (remind students to get notes into their notebooks) | After study, develop conclusions with the aid of the class (see attached notes for key content to be taught). |

| Field trip to lab site | |

| Demonstrate the steps developed in the conclusion |

Not only do teachers need to write down key content but they also need to jot down ideas on transmitting the key content to the class. They may make a note to show a slide or slides, jot down an illustration number, make a note to show a sample, work through a case problem, show an Internet site, give students a web address to view, or note other techniques designed to reinforce and apply the key content. Without these additional notes and directions, teaching becomes very superficial.

Analysis of Case 5-7. The teacher began the trial discussion to see if the class needed thorough instruction in this area or simply a review. This was accomplished by presenting students with a concrete task. The next step was to set up a division of opinion and help the students realize that they need to be more certain about how to perform this phase of the operation. This trial discussion is a mini-interest approach. It is a way to re-create interest throughout the unit of instruction.

The class begins data collection by studying in two different references under the teacher’s direction and supervision. This technique allows the students to be creative in their learning and also makes use of the principle of learning that students learn more when they inquire into subject matter than when they are instructed in it. Their task was clearly set with the use of study questions. By using the transparency, the teacher was able to specifically prepare prior to class. Notice also that the teacher was sure to develop final conclusions with the class.

The two column format for recording plans for teaching solutions to problems (or addressing questions to be answered) were clearly evident. The direction to the teacher (in the left column) consisted of phrases such as “Ask student to come forward … ,” “Demonstrate tool use,” and “Blackboard.” The key content was provided (in the right column) by attached notes, transparency content, and notes in the column that the teacher could use in securing closure.

Each problem identified in the list of questions to be answered for the unit of instruction must be planned in the manner just described. It is essential that at the conclusion of each question to be answered the class be led to develop a conclusion or agreed-on solution. In cases where several students have the problem and must solve it for their own situations there may be several different individual solutions. Then, after all the questions have been answered by the class, it is essential that the entire unit of instruction be summarized. Certainly, some of this may be done as various questions are answered (problems are solved), but often a major portion of this final pulling together is completed after all the individual questions have been answered. Students should always be directed to open their notebooks to the beginning of the unit of instruction, examine the list of questions to be answered that were developed earlier by the class, and consider the status of the problem situation (i.e., which questions have been answered and which will be answered in the coming days). A major strategy that is used in agricultural education to summarize a problem area involves providing for the application of learning.

APPLICATION OF LEARNING

The application of learning is key in agriculture instruction. By applying learning, students see its relevance, more clearly understand it, and retain it more permanently.

On concluding the solution of all the problems, a good strategy for gaining closure and moving toward planned application is for the teacher to develop with the class a list of approved practices to use for success.

Approved Practices for Success

Approved practices are those ways of doing things that are currently accepted by the industry as the best way to do them. They have been tried, through history or research, and have proved to be superior.

There are approved practices in growing corn, soybeans, fish, chrysanthemums, beef cattle, white pines, gerbils, and anything else that is produced in agriculture. Likewise, there are approved practices to follow in doing mechanical work, such as tuning an engine or sharpening a lawn mower blade. There are also approved practices to follow in completing landscape designs, grooming poodles, and making corsages.

Case 5-8: Approved practices for “establishing my home lawn”

- Grade the soil such that there is a slight slope away from the house in all directions.

- Spread high-quality (debris-free) topsoil. Apply water with a sprinkler to check for low spots.

- Till the soil to a depth of two inches, incorporating fertilizer and lime, according to soil test recommendations. Add any needed amendments. Soil should be tilled until there are no chunks larger than the size of a pea.

- Wet the soil to firm it down and wait several days before seeding.

- Spread seed evenly according to recommendations on the package. Seed twice at 90-degree angles to each pass.

- Rake seed in lightly with back side of bamboo or leaf rake.

- Fertilize at rate recommended for analysis of fertilizer used and in accordance with soil test results.

- Apply clean wheat or oat straw such that you can see 50 percent of the ground.

- Water two or three times daily until seedlings are established.

Once the unit of instruction has been studied, the teacher needs to lead the class in developing a list of approved practices. Of course, the teacher needs to have written these down in his or her plan in advance. For the sample plan on “Establishing My Home Lawn,” the list of approved practices in Case 5-8 would be written in the teacher’s unit of instruction.

Plans of Practice

Once approved practices for success have been discovered and agreed on, the teacher then guides the students in developing plans for applying what has been learned. In the case of the agriculture laboratory at the high school, it may be a production plan (drawing, bill of materials, equipment needed, procedures to follow).

In a nonfarm laboratory, it may be a list of steps to follow to complete application of learning by doing a specific job. For students who will apply learning at home via production or improvement projects, it may be a “plan of practice” such as the one in Case 5-9.

Case 5-9: Plan of practice

Establishing my home lawn

I will sow Scotts Family mixture at the rate of 13 oz per 1,000 sq ft on August 20 using a drop spreader set at the 5 1⁄4 setting. I will sow north-south and then repeat going east-west. After sowing the seeds, I will rake it very lightly and then cover with clean oat straw such that about 1⁄2 of the ground can still be seen. Then I will water thoroughly and keep moist until the seeds have germinated.

General Principles

As students develop answers to questions and lists of approved practices for problem areas, it is important that the teacher point out or help students realize general principles that can be used in other areas. General principles are broad generalizations that can be applied to other topics. They represent basic truths that are used widely in a discipline. They bring out the “why” behind fact and practice. As students learn to discover and use basic generalizations in agricultural subject matter, they have a new freedom. They are no longer locked into the specifics of facts as they apply to one situation.

In the unit of instruction on Establishing My Home Lawn, students would learn specific facts, such as when and how to sow seed, how deep to cover seeds, methods of covering them, and with what to mulch them. They also need to learn the general principles behind these facts and skills that can be transferred to other areas of turf or plant science in general. General principles such as the one that follows should be pointed out and explained.

Lawns should be established in the fall. They will develop fewer weeds because soon after the weed seedlings germinate they are killed by frost and cease to offer competition. There will also be a stronger root system because there is more moisture and evenings are cooler as contrasted with planting in the spring when each passing week brings the prospect of less moisture, and hotter days and warmer nights.

Such general principles need to be emphasized by the teacher so that students begin to realize the broad utility of their learning. When a list of general principles is developed with the class following the development of a list of approved practices, it helps unify the problem area and facilitates transfer of learning.

REFERENCES AND TEACHING AIDS

One might readily ask, “Why write down a list of references and teaching materials that are needed to teach a problem area?” The basic reason is to provide a summary checklist in order to be fully prepared for embarking on the problem area. This checklist can be reviewed prior to beginning the unit of instruction. By including such information in summary form, the teacher need not review the entire plan to determine what is needed. The best time to make such a list is immediately on completion of planning while what is needed is fresh in the teacher’s mind. The list includes, but is not limited to, books, media, equipment, web sites, materials, events, resource people, computer programs, and anything else needed to teach the unit.

EVALUATION PROCEDURE

An important part of planning for instruction involves planning how to evaluate learning and teaching. Teachers should write down their quiz questions, outlines for laboratory practical exams, and any other form of evaluation that is needed. The specifics of planning for evaluation are presented in Chapter 14.

REVISING AND UPDATING PLANS FOR INSTRUCTION

Once a complete unit of instruction is written, it will have to be revised and updated periodically. As new technology develops, key points and approved practices will have to be updated to include the current best way of doing things.

As teachers teach from a plan, they also encounter problems with students’ abilities to understand. Sometimes well-planned learning activities do not proceed as the teacher intended, hence the need to try other approaches. Then there is the gaining of new knowledge of how to teach and the development of new materials for use in teaching. Teachers will want to revise their plans to include such developments.

Some revising is done daily based on feedback from the previous day’s class. Often major revisions are made prior to the time when the unit of instruction is next taught.

Teachers need to make notes in the margins of plans and to add new pages of notes, transparencies, spreadsheets, and other aids to reflect thoughtful revisions.

DAILY PLANNING FOR INSTRUCTION

When planning for an entire unit of instruction that may last from several days to three weeks, it will be necessary to do additional planning on a daily basis. For example, the teacher may have to conclude class midway through a problem solution. The next day it is necessary to think of (plan for) a clear and logical way of reentering the problem being studied. A daily plan accomplishes just that. It serves to connect what has occurred the previous day with what is to occur in the current day’s class. A daily plan template can be developed on the computer and either printed in hard copy or used directly from the computer for the teacher to prepare for the next day’s lesson.

This daily plan is good for one time only. It is a temporary, nonreusable aid. The accompanying sample daily plan shown illustrates the concept (see Appendix A).

| Directions to self | Key content |

|---|---|

| Announce FFA meeting today 5th period | |

| Reminder of field trip tomorrow | Yesterday we discussed how to plant the seed. (Interest approach) We left off with our conclusions, which were: |

| Show Transparency 5: "Conclusions from Supervised Study" (question 5). | (Content is listed on overhead) |

| Write objective on the board | Today's objective: Practice the planting procedure on one of the plots after the demonstration. |

| Field trip to demonstration plot | Supplies needed Take: • Rakes (5) • Wheelbarrows (3) • Shovels (4) • Carton seeder • Drop seeder • Cyclone seeder |

| Opportunity to learn: Students will show me they can properly use the equipment to plant the seed according to the process we studied. | Today we had the chance to apply the seed at the proper rate following the procedure we learned in class. Tomorrow we will take the field trip to the lab. |

Notice that the daily plan includes routine notes such as announcements, reminders, and assignments, as well as connecting comments for the teacher to bridge previous learning with today’s lesson and future lessons. It also has a brief overview of the current day’s class to provide a clear mental set. There is also a new interest approach for the day’s class.

SUMMARY

Planning for instruction is the key to becoming an effective teacher. It forces the teacher to be clear about what is to be accomplished, the content to be included, and how the content is to be delivered. Thorough planning allows for flexibility and spontaneity because the goal or end product are always in sight and serve to refocus the teacher and learners.

In planning the unit of instruction, the teacher makes predetermined use of the principles of learning and the techniques of teaching. This is where each individual’s creativity and worth as a teacher is displayed. Once teachers master the ability to plan well, they are free to enjoy teaching.

FOR FURTHER STUDY

- Select a problem area and develop a unit of instruction around a list of questions to be answered. Check it against the suggestions offered in this chapter.

- Ask your teacher educator for some sample units of instruction that you can compare to the suggestions made in this chapter.