8 Managing Student Behavior

Recently, a day was spent in a local department of agriculture videotaping the techniques used by the teacher in that department. It was a wonderful experience. Anyone who was interested in teaching agriculture could not help but enter the profession if she or he could see the admirable job of directing learning that was talcing place in this desirable environment for learning.

Of prime importance, the teacher acted like a teacher. She was in the room, ready for class, and showing her personal interest in each individual student well before each class began and well after each class ended. She was warm and caring. She came across as being genuine, being herself and enjoying it. Her techniques of teaching and dealing with students fit her personality rather than running contrary to her real self.

Another striking element of what contributed to this atmosphere was that the teacher knew her subject. She was technically competent and caused students to clearly understand the points of her lesson.

The teacher’s rapport with her students was as near perfect as possible. The teacher and students knew one another and respected one another. They listened to one another. Each party contributed to the development of the lesson. The students and teacher could and did laugh together while balancing the allotted class time with on-task productivity.

The lesson was organized and clear. The students had been taught how to study and learn according to the approach used by the teacher. Students clearly knew what behavior they were expected to display.

The teacher did not shout, nor did she publicly confront her students. A word, a look, a direction was all that was needed.

It was obvious that the teacher personally knew the students and their parents and home situations. She built on this knowledge and skillfully provided for individual differences. The students were the center of their own learning and were responsible for their own actions.

Truly, this was a desirable learning environment, and one that most teachers can achieve. But many teachers do not have such an environment, and very often it is the teacher’s practices as much as the actions of the students that contribute to an undesirable learning environment. Consider the following case:

This was a class where the students were in the room walking on top of the tables when the agriculture teacher arrived. The teacher screamed at the students until they began to get to their seats. After a five-minute delay while the teacher tried to get some notes together, class began.

There was a no interest approach. The teacher talked at the students but the flow of the talk was confusing. It was obvious that the teacher did not care for the students and they shared this feeling. As the class continued there was a continuous verbal war between the teacher and the students. The teacher was unhappy and so were the students.

Now this situation did not always exist. The situation evolved to this point.

How could the teacher with the desirable learning environment have it so good, and the teacher with the undesirable learning environment have it so bad? Certainly, there is no clear-cut answer. Yet, those who study these matters know that both situations are primarily the results of the teachers’ actions, attitudes, and abilities.

OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you will be able to

- Identify the techniques of successful teaching that are positively related to successfully managing student behavior.

- Identify and use an array of specific strategies to effectively manage student behavior.

- Develop ways of using parents in promoting acceptable student behavior.

- Help students learn to accept responsibility for controlling their own behavior.

THE TEACHER AS THE KEY INGREDIENT FOR AN ACCEPTABLE CLASSROOM ATMOSPHERE

Without a learning environment that includes students whose behavior is acceptable, it is virtually impossible for students to learn. Students cannot give their attention to the task of learning and simultaneously view the performance of the class clown. Likewise, it is impossible for teachers to involve students in a clear and organized presentation if they must constantly stop to restore order. Without good class control, teachers cannot be effective teachers. Thus, a major challenge for teachers is to manage their classrooms so as to create a desirable learning environment.

School administrators and the public as well are critical if teachers cannot control their students’ behaviors. The annual Phi Delta Kappan Gallup Poll consistently reveals that one of the public’s chief concerns with education is discipline in the schools.

Not only is the effective management of the classroom important because of its impact on learning and its necessity in the eyes of the administration and the public but effective classroom management is also closely associated with one’s satisfaction with teaching or lack of such satisfaction. No matter how competent teachers are at teaching, they must manage student behavior successfully or they will dread entering the classroom because of impending discipline problems. In such cases, they will not be able to perform as adequately as they are capable of performing.

Remember, just as the first situation referred to in this chapter did not occur overnight, neither did the second situation. Rather, classroom atmospheres are generated; they evolve. In the case of discipline problems, they often evolve so slowly that teachers are not fully aware of what is happening until conditions have deteriorated to a state of crisis.

Perhaps the following analogy will help to illustrate the point of not waiting for a crisis to develop before taking positive action. Frogs, unlike most animals, are not able to perceive gradual changes in the temperature surrounding them. In fact, if a frog is placed into a pan of water, and the water is gradually heated, the frog will complacently sit in the water as the heat rises to the boiling point. The frog does not feel the heat and thus does not make a change in the environment. The same seems to be true of many teachers. They step into a typical classroom and are so naive that they fail to detect the gradual “heating up” of the environment until at last they are “sacrificed.” An early detection system is essential in maintaining classroom discipline. This is part of the art of teaching for which teachers must develop a “sense.” There are no readymade recipes. However, there are some specific skills we can master that will help in successfully managing student behavior.

THE RELATIONSHIP OF TEACHING PERFORMANCE TO PROMOTING APPROPRIATE STUDENT BEHAVIOR

The Effect of Technical Competence

Before teachers can teach well they must be very knowledgeable about their subject areas. If the teacher does not have a firm understanding of the subject matter, it is difficult to perform well as a teacher. Teachers must be technically competent. No university can teach an agriculture teacher all that is ever needed. Agriculture teachers must accept the responsibility to continue learning what they do not know as such knowledge and skill is needed.

Teachers who clearly know their stuff are able to teach with confidence and authority. This sense of being taught by a pro does much to dissuade students from being tempted to behave unproductively during class because the students are able to sense that such teachers know their subject matter and probably know how to handle students who behave inappropriately. However, when students sense that a teacher is not well informed or up-to-date, they find it hard to resist exploiting such a weakness.

The Effect of Rapport on Maintaining Acceptable Student Behavior

Another crucial ingredient in teaching performance that enhances appropriate classroom and laboratory control is good rapport. Teachers who are able to develop good rapport with their students are apt to have fewer problems than teachers who lack this quality.

For example, there was a young agriculture teacher who enrolled in a first-year teacher program where a member of the agricultural education department at the university visited the teacher regularly. As the year progressed the teacher educator sensed that the teacher’s classroom control was deteriorating. After some questioning, it was learned that this teacher, who was single, spent time most evenings at the local cafe. This was also the gathering place for the local students, and progressively the students and the teacher became overly familiar with one another to the point that this familiarity transferred into the classroom. Once the teacher realized what was happening and ceased to visit the cafe, the classroom situation improved. Professional distance was restored. This professional distance is necessary.

The relationship that teachers seek with their students is one of reasonable give and take. Teachers must listen, evaluate, and then act rather than jumping on students before they have had a chance to adequately explain a situation. Teachers must also have a sense of humor and be able to laugh at themselves and with their students. For example, if a teacher makes a mistake at the board, he or she ought to be willing to let students have a laugh without becoming defensive. Likewise, when students say something that is in error, the teacher and the other students ought to be able to laugh with the student without the student feeling that he or she is being laughed at. It is imperative that teachers remember that students have feelings and that sarcastic remarks can hurt. Students also have egos, and many of them do not hesitate to defend their egos when they are confronted or put on the defensive in public, especially in front of their peers.

The Effect of Interest on Student Behavior

Given that one has the proper climate for good class discipline, there are a number of points regarding teaching techniques that affect discipline. Students are not apt to cause difficulties if (1) what they are taught is interesting and (2) it is taught in an interesting way. It is unrealistic to expect good behavior from students when they are being taught material that is not relevant to them presently or in the foreseeable future. Likewise, class behavior is generally not good when students are asked to learn more than they need to know in order to satisfy their own goals.

Even if what is taught is important and interesting to students, it must be taught in a manner that is interesting. Students must be mentally set in order for learning to occur. Interest must be gained at the beginning of every teaching session. The few minutes it takes to think of an interesting way to begin a lesson is much more productive than the time it will take to keep order during a boring class. One must have control of the class’s behavior and must invest the time and energy required to gain and maintain the interest and appropriate behavior of the students. However, interest is not permanent. Therefore, students have to be “reinterested” during the class session.

There are many ways to generate and maintain interest, but the total design will certainly include and demand several changes of pace each hour. Consider Case 8-1.

Case 8-1: Generating and maintaining interest

Question to be answered: “How do I determine the size of a freshwater pond?”

| Direction to self | Key content |

|---|---|

| Distribute the following problem to the class | "We have a problem. Our class is to 1. Fertilize the fish pond in our nature preserve and 2. Apply herbicides to control undesirable vegetation. Before we can figure how much fertilizer and herbicide to buy we must know the (a) acreage and (b) volume. "John would you explain how to figure the acreage of a circular pond as well as its volume?" Assuming he doesn't know how— "Do we need to figure out how to calculate this before we can proceed?" |

| Divide class into two groups | |

| A. Have one-half of the class read pp.13-14 of "Managing Freshwater Ponds" and determine how to figure surface area. | pp. 13-14 of "Managing Freshwater Ponds" (attached) |

| B. Have the other half of the class read pp. 14-16 of "Managing Freshwater Ponds" and determine how to calculate volume. | pp. 14-16 of "Managing Freshwater Ponds" (attached) |

| Show Transparency 1 | Formula: Surface area = |

| Show Transparency 2 | Formula: Volume = Surface area * Average depth |

| Students write: After study, have one person from each group put an answer on the writing surface. | Problem 1: Circumference = 780' Average depth = 11' Solution: |

| Overhead: Work through a sample problem on overhead | Answer = 1.1 acres |

| Handout second problem for practice | Problem 2: Circumference = 500' Average depth = 7' Answer: Surface area = 0.46 acre |

| Students calculate surface area and volume of school pond during laboratory | (Opportunity to show they learned the content) |

| Summary | "We have learned to calculate pond average and volume. Now we are ready to proceed with solving our problem. What else do we need to know?" |

Analysis of Case 8-1. Notice that distributing a real problem generated interest. Because the students will actually do the work referred to, they will likely want to know how to proceed and will generate quality questions to be answered because they can see themselves in the situation.

In teaching the solution, notice that the teacher involves students in supervised study (reading and solving problems), putting answers on the board, and taking measurements during lab. Each of these activities, as well as the teacher using the overhead projector and helping all the students as they do sample problems, is an effective change of pace. Thus students are not required to maintain their interest for long periods of time. The teacher has built into the teaching relief from naturally occurring boredom.

Students have high energy levels and they must have ample opportunity to expend this energy. If the teacher does not sufficiently involve students in class to help them productively expend their energy, the students will create their own ways to expend their energy, and their creative ways of being energetic generally are troublesome for the teacher. Thus, the teacher must realize this wholesome aspect of the adolescent and teach with sufficient variety and involvement such that discipline problems are avoided rather than created.

The Effect of Organization and Clarity

Not only must the instruction that is provided be taught in an interesting manner, it must also be presented in a clear and organized manner. Teachers can be filled with enthusiasm and change the pace often, but if they confuse their students, the students will soon give up in frustration. It is not enough to entertain. A teacher must also help bring about a change in the behavior of students. Learning must take place, and organization that brings clarity (note the flow of events in Case 8-1) promotes effective learning.

Students in the class where Case 8-1 occurs have a clear frame of reference (their school pond problem) and adequate structure for learning (the formulas and practice using them). Without such a framework, the class becomes confusing. With confusion comes an increase in frustration and anxiety. As the level of frustration and anxiety rises within a student, the student becomes increasingly impatient and resentful. Once a student is in this state of mind he or she is easily provoked and may, in fact, create trouble in the classroom simply to relieve the frustration.

Teachers can make additional use of providing structure by reminding students that they are systematically developing increasing levels of competence. This can be accomplished, for example, by reminding students who have learned to sterilize soil, propagate poinsettia cuttings, and stick rooted cuttings that, after studying two more problems, namely growing poinsettias and marketing poinsettias, they will be able to produce a crop from start to finish. Another way to help students realize that they are systematically developing competence is by using skill charts and record books.

STRATEGIES FOR PREVENTING STUDENT MISBEHAVIOR

No one can prevent inappropriate student behavior for the teacher. Teachers must do it themselves. Only you can manage student behavior. Suggestions that consistently work will be offered, but the individual teacher has to implement those suggestions. In using the various suggestions that are offered, teachers must also keep in mind the principles of learning presented in Chapter 2. Thousands of teachers learn what to do, when to do it, and how to do it, but they attempt to succeed by using only a small number of the numerous resources available, and they usually fail.

Maintaining desirable student behavior is heavily predicated on prevention. If student misbehavior is not allowed to begin, it does not have to be stopped. Thus, the more you manage the classroom, the less you have to discipline the students.

General Guidelines to Follow in Promoting Acceptable Behavior

Before suggesting specific strategies to use in securing appropriate student behavior, consider the following general guidelines that teachers find helpful. These are guidelines on which there is rather common agreement by practitioners and theorists alike.

In addition to these guidelines, teachers must remember that they are a part of the school system and as such must operate within school policies. Teachers cannot expect the administration to allow them to violate general school policy, even if the teacher disagrees with it. Such actions would create an unmanageable situation.

- Start out firm. One can always ease up later, but the opposite is not true. Remember that people are greatly influenced by first impressions. Teachers must realize that once a pattern of operation and behavior has been established, it becomes the norm and is very difficult to change. So, the questions, “What will I do?” and “What will I say?” on opening day are critical. Start planning for these questions now.

- Be prepared to teach well. Keep students busy in a meaningful way. In other words, do not simply assign busywork; rather, have students actively involved in doing things that make sense to them. Many behavior problems are created because teachers are late in arriving to class, do not have definite instructions planned for the day, and allow students to become bored.

- Have a definite routine by which each class is started. A routine may simply involve taking the roll, making announcements, and explaining what will be accomplished that day. A “bell assignment” (a question for students to answer, a reflection for students to write from the previous day’s notes, a seat activity, or other short, quiet writing assignment) written on the chalkboard, whiteboard, or projected on the overhead works well for this time period. A part of this routine should include the teacher always being in the classroom or laboratory before students arrive to greet students as they enter the room. The existence of such a procedure creates an environment of certainty and security. Students quickly come to know what to expect, and they get in to a habit of acting accordingly.

- Make generous use of praise. Encourage good behavior and let students know that they are appreciated. All people enjoy the feeling of being admired, appreciated, and acknowledged in public. Students who experience praise for good behavior and good schoolwork will tend to repeat such behavior. Know your students so you know whom you can praise publicly and whom you must praise privately.

- Do not have favorites. Each student is a person of worth. Students dislike getting the sense that the teacher has predetermined their destinies as angels or demons.

- Be consistent, yet not predictable. Although this may seem ironic, it is not. Teachers need to be consistent. When inappropriate behaviors occur, the students involved must know that such misbehaviors will (a) be dealt with and (b) be dealt with fairly. However, it is not in a teacher’s best interest for students to be able to predict specifically how a given inappropriate action will be handled; they then know how much risk is involved whenever they misbehave. Knowing the precise degree of risk prompts some students to decide, “Well, that is not so bad—it will be worth it just so I can … “. For example, if a student broke a glass in the greenhouse on purpose he or she should know that the teacher will punish him or her. However, the student should not know whether the punishment will consist of paying for the damage, working extra after school, or having the parents in for a conference. A teacher must consistently punish such misbehavior, but not in predictable ways.

- Take action whenever a problem arises. Granted, a teacher should not discipline students when the teacher is angry. However, it is unwise to postpone handling problems because students interpret this as weakness and indecisiveness. Although teachers may want to wait until a planning period to specifically deal with a problem, they should let the student know at the time of the misbehavior that it will be dealt with at a certain time.

- Learn to separate the action of the student from the person of the student. What is meant here is that the teacher needs to communicate to students that the teacher dislikes a certain behavior and will not tolerate it but does not dislike the student. The student is a person of worth and is appreciated, but the behavior will not be tolerated.

- Never make threats, only make promises. Students soon learn the idleness of threats. When teachers say, “If you do that again, I’ll break your neck,” students know full well it is not going to happen. However, when students learn that if a teacher says something will happen then they can count on it happening, students are much less likely to press the issue. For example, if a teacher tells students that there will be no more field trips if they throw objects out of the bus again and they disobey, then end that field trip and future field trips as well.

- Set a good example. Students need role models. They also appreciate people who practice what they preach. If teachers want students to be serious, productive, on time, and well mannered, teachers must act accordingly.

- Be sure the penalty fits the offense. Teachers must learn to gauge their penalties to the degree of seriousness of their students’ misbehaviors. No matter who the student is who misbehaves in a given way, that student should be dealt with at the same level of severity as other students who may have misbehaved similarly.

- Be attentive to all behavior in the classroom or laboratory. Students are quick to take advantage of teachers who are able to see only one thing at a time. Teachers must learn to be very observant; otherwise, irritating little problems increase until they are out of control.

- Learn to forgive and forget. Teachers who hold grudges will not be very successful. All people make mistakes. Once a student’s mistake has been dealt with, the student should not be constantly reminded of the past failure. If a student curses you, then once you have satisfactorily handled the misbehavior, be willing to say to the student, “OK, now let’s forget it,” and do so.

Beyond these guidelines there are some specific strategies that have been found to be helpful in promoting appropriate discipline. A real cornerstone of a discipline program is the establishing of clear expectations regarding student behavior.

Setting Expectations

The most important time to discuss discipline is the first day of class. This is true whether one is a student teacher taking over a class, a first-year teacher on a new job, or an experienced teacher meeting a class for the first time.

A firm but fair beginning is crucial. The tone that is set at the beginning will temper all that follows. A procedure, delineating points to be discussed during the opening day expectations, should be presented. However, keep in mind that what each individual teacher does must be consistent with established policy in the school. Likewise, each teacher must use an approach that is congruent with his or her own personality and mode of operation.

In opening a discussion of discipline with a class, it makes sense to begin by letting the students know that you are just as normal and human as they are and that you have a personal life outside the school. If you are married, tell them. Chat with them briefly about your spouse and children. Share a few of your background experiences and current hobbies and interests. You might be surprised how interested students are to learn that their teacher played a saxophone in high school, enjoys scuba diving, is an accomplished photographer, and so on. An additional benefit of this kind of a beginning with a class is that it helps break the ice. Naturally, you should not discuss private, personal details or reveal so much that you lose what is called professional distance.

After the period of breaking the ice, open a discussion that encourages students to provide a list of what they expect from the course. This is easily accomplished by asking students questions such as, “What do you expect to get out of this course?” “Why are you enrolled in this course?” “What are some things you expect to learn here this year?”

Students generally give some rather sensible responses to such questions, but they may have to be encouraged or prompted to speak up. They will probably say things such as, “I want to learn how to be a better … (whatever career for which your program is geared),” “I want to become a state FFA degree winner,” “I want to learn how to … (perform some specific task).” This list should be recorded on the writing surface (and in their notebooks) so that students realize (1) you are serious, (2) you are businesslike, and (3) they are expected to take notes and pay attention from the very first day of class to the last day.

Students should realize that unless they have some rather valid reasons for being in a class and unless they are expecting some general kinds of things to be delivered, they may be disappointed. Notice the psychological importance of this strategy. Students will develop the feeling that they are able to affect the direction of the class, and such a feeling provides important psychological comfort. Be sure to maintain firm control of the class during this dialogue.

Once students have revealed their course expectations, it is important to move to a more personal level. Find out from the class what they expect of you. This will require even more probing, but it is essential that students express realistic expectations of the teacher. One strategy is to ask each student to write at least one realistic expectation on notebook paper before opening a dialogue. Once again, use leading questions that will prompt the types of responses that are needed. It may be necessary to point out that this is the chance of their lifetime; but do not become too informal at this point because students may misinterpret such informality as an indication that this is a big game and may thereby be encouraged to be too rambunctious too soon. Also do not accept any smart answers at this point. Students will probably suggest things such as “be fair,” “don’t be too hard,” and “keep us interested.” These responses should also be listed on the board for the same reasons you had them record their expectations for the class. Again, the psychology of this step is very important. Students have had a chance to say this is what they want their teacher to be, which builds a beautiful foundation for the next step.

The next step is to present the class with this question: “What should be the mode of operation for our class?” Here, have the students collectively formulate some general operating procedures. Once again this can probably best be done by asking some leading questions such as, “What should be the general way in which we will operate our class?” “Would you suggest some general guidelines that we should follow as we conduct our class during this year?”

However, avoid a list of rules. Remember, for every rule there must be penalties, exceptions, enforcement, and many other associated problems. Being overly specific only highlights areas of possible violation and, in fact, can provide an irresistible inducement for some students. According to Smith and Smith, “This new rule creates a new environment which must be tested. A child must break the rule, usually several times, before he [sic] is sure it is truly in effect.”[1] Thus, it seems appropriate to create an atmosphere of general understandings as to what is acceptable and unacceptable behavior rather than to prescribe in legislative fashion every activity that is considered inappropriate.

When generating this idea of “How should our class operate?” a student or students may offer specific suggestions, such as “We shouldn’t throw spit wads.” This is a good time for the teacher to help the class see that we as mature students (this lets students know you realize they are more than little school children) know right from wrong and that we must be mature. Thank the student for the suggestion, acknowledging that it is a correct notion, but point out that we need only list more general understandings such as abiding by school rules, treating one another courteously, or putting forth our best effort.

Finally, and most importantly, teachers need to clearly and positively explain their own expectations of the students. This is the place to discuss absolutes, whatever they might be, for the teacher. Some examples are arriving on time (and explain that you believe on time means in your seat with your notebook and a pencil before the bell rings), being prepared (i.e., assignment is read, pencil is sharpened), doing honest work (i.e., do your own homework), using only appropriate language (i.e., only use words you would write in a graded English essay), not giving passes to the restroom, or whatever absolutes you feel strongly about. Teachers need to explain their idiosyncrasies and personal biases so that the students realize that the teacher knows this is his or her issue, but that if students prey on that issue, they can expect quick action. Teachers need to let students know that they realize this may be something peculiar to them, but that is the way it is. By alerting students of such specifics, they can stay clear of them rather than encounter them, thereby provoking the teacher unnecessarily. Discretion must be used at this point. Only the most important items should be discussed, and teachers should be sure they do not establish absolutes that they have no personal right to establish.

Once teachers have established this basic set of expectations and understandings, it is important to do some teaching. Even if they have to deal with a rather short lesson, they should do so. Remember the importance of first impressions. The teacher should teach as well as possible. An important psychological advantage of providing some masterful instruction at that first meeting is that it lets students know the teacher is very serious about the course and that this teacher is there to teach.

In summary, a teacher’s brief outline of the key points to discuss with the class in establishing a basis for managing student behavior might look like this:

- Personally introduce yourself, your background, and the nature of the course.

- Have students tell you what they expect from the class.

- Have students tell you what they expect of you.

- Discuss how the class should operate.

- Tell the class your expectations and the little “things” you will not tolerate.

- Teach some agriculture as effectively as you know how.

This first session is not meant to be a sermon. Rather it should be a businesslike discussion that establishes the setting in which the students and the teacher should operate. Students should go home with the impression that this is a teacher who acts with authority but is also there to help students grow and develop into the kind of people they ought to be. If the items previously discussed are not implemented during the first class session, they become essentially useless. There is little value in waiting until Thanksgiving or Christmas to discuss the expectations of the teacher and student because by then it is too late and, therefore, seldom works.

Teachers who realize that good discipline is essential and use the procedure discussed for establishing expectations regarding student behavior are well on their way to developing the kind of basis that is needed to promote appropriate discipline. During this process we must also realize that another key ingredient for successful classroom management is humor. Teachers must be willing to laugh at themselves and with their students. Although teachers should and must conduct themselves in a businesslike manner, they must also establish rapport with the class. Effective disciplinarians do not have to be steel-hearted monsters with no personal concern for their students. Quite to the contrary, effective teachers must know their students, that they care about them, and earn their respect.

Knowing the Student as a Person

Real cooperation between students and their teacher becomes possible when they care for one another. Teachers must provide quality learning experiences that show they care for students. To do this, teachers have to get to know their students. There are many good ways to accomplish this objective. Perhaps the best way to really get to know your students so that you can show you care in personal ways is to acquaint yourself with their home situations. Case 8-2 illustrates the point.

Remember, too, that students have interests and talents that may not surface in the agriculture course. They may be artists, musicians, dramatists, or athletes. If they are, you can bet they want their agriculture teacher to see them perform and be proud of their accomplishments. Teachers of agriculture need to attend general school functions, thereby showing their students that they (the students) are persons of worth and are cared about.

Case 8-2: The case of the long walk

An agriculture teacher found he was required to visit his students in their homes. From this experience he concluded (and you will too) that home visits are essential to providing the best instruction possible. One balmy spring day in the Blue Ridge Mountains a shy boy in the back of the room sheepishly raised his hand and said, “Would you come out to my home this afternoon and help me figure out what is wrong with my chickens?” What else could a young, inexperienced teacher say but “of course.” Then the boy, Jackie, said, “You’ll have to walk a long ways.” Again, what could anyone who cares for people say except, “That’s OK, no problem.”

They drove a pickup truck as far as possible and then walked an additional three miles to reach his house. His chickens lived under terrible conditions, and there was clearly the need for much help and individual instruction. They then went to the house to meet his mother. Entering the house was easy on that beautiful spring afternoon, for the doors and windows were open and there were no screens. They entered the kitchen and the teacher saw the student’s two younger brothers sitting on the floor eating their supper—beans and biscuits. Green flies swarmed as they entered the room; his rooster was sitting on the refrigerator. His mother was standing by the sink. They walked over to meet her. She was a large lady, plainly but cleanly dressed. She was obviously apprehensive.

Jackie introduced his agriculture teacher, and the teacher and Jackie’s mother began to chat. Early in the conversation she said, “Oh, won’t you stay and have a bite to eat with us?” She was a good, kind lady. She was a person of worth. She cared about her children. That and subsequent visits had quite an impact on the agriculture teacher. He taught Jackie differently after that because he could relate his instruction to him in a more personal way.

Jackie and his agriculture teacher cared more about one another after that. The teacher was able to better understand why Jackie was the way he was. Thus, the teacher no longer expected Jackie to write a report from the farm magazines he read at home because there were none. Jackie was not hassled with having to do improvement projects that were unreasonable under his circumstances. Rather, his improvement projects were carefully selected based on his needs and resources. This personal knowledge of Jackie helped his teacher to be more effective.

Using the preceding discussion to gain a better understanding of students will result in an improved relationship between teachers and their students and, thereby, improve the climate for effective discipline. However, given all of the previously mentioned background and preventives, there will still be discipline problems that will arise and will require positive teacher action. Teachers can be sure that no principal wants teachers to send him or her their discipline problems. Sending anything but a real crisis case to the principal only tarnishes the image of the teacher in the eyes of the administration. When you have recurring problems with a student, you may want to counsel with the appropriate administrator regarding next steps. By showing the administration that you are aware of a problem, have taken specific action, and have sought advice, you build a foundation for strong support in the event that you must refer the case to the principal or other administrator later. There are no panaceas, no magical cures. Several strategies are suggested from which the teacher can make prudent selections. Teachers will need to develop their own fortes of discipline techniques that they find are successful for them with their own students.

STRATEGIES FOR DEALING WITH STUDENT MISBEHAVIOR

Withholding Reinforcement

Very often discipline problems arise when some students need to have extra attention. This type of student is often willing to take seemingly large risks in order to receive direct attention from the teacher, even if the attention is extremely negative. Likewise, such students are almost certain of receiving attention from their peers, for students often love the antics of a classmate.

Unfortunately, many teachers fall into the trap of reacting to a student’s ploys and thereby satisfying (or reinforcing) the student’s need for attention. When the teacher takes time to deal with such a student during class, the teacher has, in effect, done exactly what the student sought to have done, namely receive personal attention and not have to study agriculture. Thus, the behavior of the student, which was inappropriate, triggered the teacher to react, thereby doing precisely what the student set out to make happen. Naturally, the next time the student feels the need for teacher attention, all he or she has to do is misbehave and the vicious cycle is reenacted. Such a progression of action puts the student in the offensive court and forces the teacher into the position of reacting in a defensive posture.

Actually, the teacher would be better off ignoring some undesirable behaviors. By ignoring the behavior, at least publicly, the teacher does not provide reinforcement to the student in the form of the student gaining public attention, and the behavior will often become extinct.

The key for the teacher who desires to promote acceptable student behavior is to learn to perceive when misbehavior is aimed at gaining attention, then to refuse to fulfill such needs by reacting in public. Obviously, this does not apply to all behavior problems. There will be instances in which an individual or an entire class needs to immediately be corrected publicly when a disruptive behavior occurs. For example, if the class bully is physically abusing the class underdog, he or she must be stopped and dealt with then or after class. If the whole class is unruly, the teacher must stop the unruliness and regain the attention of the class. The essential ability or art that a teacher must possess is to distinguish between (1) behaviors that can be extinguished with firm action and (2) behaviors that are designed to fulfill one or two students’ need for pampering or to merely direct the teacher’s energies away from promoting learning and toward wasting class time.

Deal with students seeking recognition by this means on an individual basis. Keep such students after class, call them in during a planning period, or deal with them after school. One can effectively deal with the problem without wasting class time chastising a student before the whole class, when the student, at whom the comments or other strategies are aimed, cares little about the punishment and in reality enjoys the treatment.

The wise teacher will learn to provide personal attention and visibility to students when they are not misbehaving. This shifts reinforcement and teacher attention to appropriate behaviors while at the same time meeting a student’s need to be accepted, recognized, and valued.

Using Suspense

In dealing with student behavior problems, often one of the best strategies to employ is the use of suspense. Keep students wondering what you will do and when. If they can predict a teacher’s reactions, they know the amount of risk involved in deviating from acceptable patterns of behavior. This often encourages students to behave unsatisfactorily.

Likewise, in disciplining students, teachers must take their time. Allow students to wonder what is coming, to weigh the seriousness of their actions and what the proper consequences of such actions might be. Often the mental anguish is more effective than any specific disciplinary action the teacher might take. This course of action also gives the teacher time to think, and if the teacher is emotional, there is time to remove such emotion from the corrective actions that are taken.

Using the Individual Conference

One of the most effective strategies available to the teacher in managing student behavior is the use of the individual conference. There are several advantages offered by dealing with a student in private. First of all, the confrontation is on the grounds of the teacher. There is no audience for which the student can perform. Neither the student nor the teacher has an image to project or protect, and both parties will have the opportunity to be less emotional and more rational. For the most part, teachers come to regret dealing with class disruptions while they are angry.

Rather than deal with a nagging student in the classroom or laboratory, it is often to the teacher’s advantage to tell the student, “See me after class.” Then before the class is dismissed, be sure to remind the student to stay . Whatever the problem, if it will take more time than is available at the moment, the student should be told a specific time to see the teacher. The waiting that the student experiences from the time the conference has been arranged until it actually begins is often very helpful in changing the student’s attitude and the teacher’s emotional state. Students also have time to think about their actions and to vicariously act out their emotions before they and their teacher have the individual conference.

Once the conference begins, the way the teacher handles the conference is extremely important. For rather serious behavior problems the following procedure is suggested. Begin by questioning the students until they admit why they are there. This often takes as much as five or ten minutes. Do not rush it, and unless a student is unmalleable, do not tell the student why he or she is there. Unless the teacher has acted very capriciously, the student knows why he or she is there.

The beauty of this phase of the conference is that students have to admit that they made an error, that they knew better, and that there is justification for the conference. This in and of itself gives the teacher a psychological advantage. The students have in effect pleaded guilty. They have said, “I am wrong.” Having such an advantage, the teacher should build on it. Students also need to understand why their behavior was wrong.

The next phase of the conference involves getting the students, through a series of leading questions, to realize that their behavior choices have been a disappointment to people who care about them, including parents, girlfriends or boyfriends, peers, and the student who is the focus of the session. Rarely should the teacher encourage or allow students to discuss whether they have disappointed the instructor conducting the conference. When students have very much respect for their teacher, they are not involved in a conference of this kind.

In order for this phase of the conference to be effective, it is imperative that the teacher be familiar with the home situation of the student. It will obviously do little good to attempt to get students to admit they have been a disappointment to their parents if there is no feeling of respect between the student and the parents.

The teacher is now at a point where consequences must be discussed. Rather than automatically doling out a penalty, have the student suggest what it should be. This is another area of the conference where there is no need to hurry. Time for the student to think of suitable consequences for the offense may be more important than any penalty per se. Having students make the suggestion for the penalty causes them to weigh the seriousness of their misbehavior. Additionally, students are forced to begin accepting responsibility for their behavior.

It is often desirable to reject many, if not all, of the consequences suggested by the student. There is a basic reason for this suggestion. Many of the penalties students suggest are not very realistic; they are either too severe, or not the type of penalties the teacher believes in (such as writing sentences or corporal punishment), or do not align with the misconduct. When such consequences are suggested, teachers should explain to the student why the teacher believes the penalty is inappropriate. Also, if the conference has caused the student to recognize his or her problem and admit the action was inappropriate and deserving of a penalty, the student’s attitude has probably been changed, which is what the teacher seeks anyway.

After careful consideration, a consequence may be selected. However, if the conference has gone well, the teacher may decide there is no need for any penalty because the student’s attitude has improved. In this case, teachers may tell students that they believe the situation has been taken care of, that it will not arise again, and that if it does arise again an appropriate consequence will be waiting. This cannot be a bluff. Teachers must become known for being fair and for acting decisively when a situation does not improve.

Regardless of whether a penalty for the misbehavior is assessed, it is important to have the student (you may have to help) review the major happenings of the conference. Thus, students, in reviewing the conference again, admit they were wrong, realize they have been a disappointment to some people they care about, and suggest a penalty. This helps crystallize for students what has happened and allows them to leave with a clear notion of what is expected and will be tolerated. An outline for an individual conference might look as follows.

Outline for an Individual Conference

- Get the student to explain why he or she is in the conference—to admit he or she did something that should not have been done.

- Get the student to realize his or her actions have been a disappointment to some people he or she cares for—parents, friends, class members, self.

- Have the student suggest a consequence that will guarantee the action will not occur again.

- Have the student review the major points of the conference.

Without a doubt, if the conference is handled well, it will alter the student’s behavior. There have been no public scenes and no hideous actions. The student has essentially been held accountable and taken full responsibility for the behavior.

When students leave such a conference, their friends will ask what happened. What will their reply have to be? What can they tell their friends? Essentially they will say the teacher did nothing, especially if no penalty was given. The teacher did not give them detention or take away a privilege. “The teacher simply talked to me,” they will say. However, if the student acts much differently in class the next day everyone will certainly wonder what happened. The only way other students can be sure of what happened is to receive a special invitation so they can experience it personally. For most students, the risk will be too big to take.

In conclusion, examine the psychological advantage this type of approach gives the teacher. Students admit they were wrong, that they did something that was unacceptable, that they are guilty. Then students admit some special people will not be very proud of them when they find out what happened. The students then agree they should be penalized for their actions and they personally try to identify an appropriate penalty. Then the teacher forgives all and assures the student that appropriate action will be taken if this happens again. Notice, the student has made all the tough decisions. This has a tremendous sobering effect on most students.

For times when something has to give, the individual conference works as well as any discipline strategy available. Obviously, the strategy is reserved for more serious situations. Examples of such situations are flagrant acts of destruction, such as marring furniture or equipment; fighting; verbal abuse of teacher or peers; outright belligerence, cheating, or stealing; or having tried you as a person one time too many. There are other techniques for less severe problems.

Use of Volume

The first thing that probably comes to the minds of most teachers when they think of using volume to manage student behavior is loudness. This is not necessarily so, for loudness only allows one to make use of half of the strategy of volume.

Certainly, a shout from the teacher can startle a class and cause the students to give the teacher their attention. Likewise, teachers may raise their voices and lower them to create interest, which is a positive way of preventing student misbehavior.

Teachers have to be careful, however, not to try to out shout a class. New teachers often discover that the sound level in their classroom has gradually grown to the point that the class discussion has become a shouting match. This type of environment only serves to create tremendous tension for the teacher and students alike. Loudness seems to work best where it is used as a shocking force. It should not be used constantly or it will lose its effectiveness. If the teacher and students are always loud, the teacher’s plea for quiet will likely go unnoticed. It is much like hearing an air hammer working outside of an airport. It goes unnoticed. It is simply one more loud noise.

Certainly, one can use reduced volume just as effectively in controlling a class. When teachers develop enthusiastic discussions, they must realize that this method breeds noise. The noise level can often be controlled if teachers will merely drop their volume to just above a whisper. Students then find that they cannot hear unless they lower their voices, or better yet, stop talking.

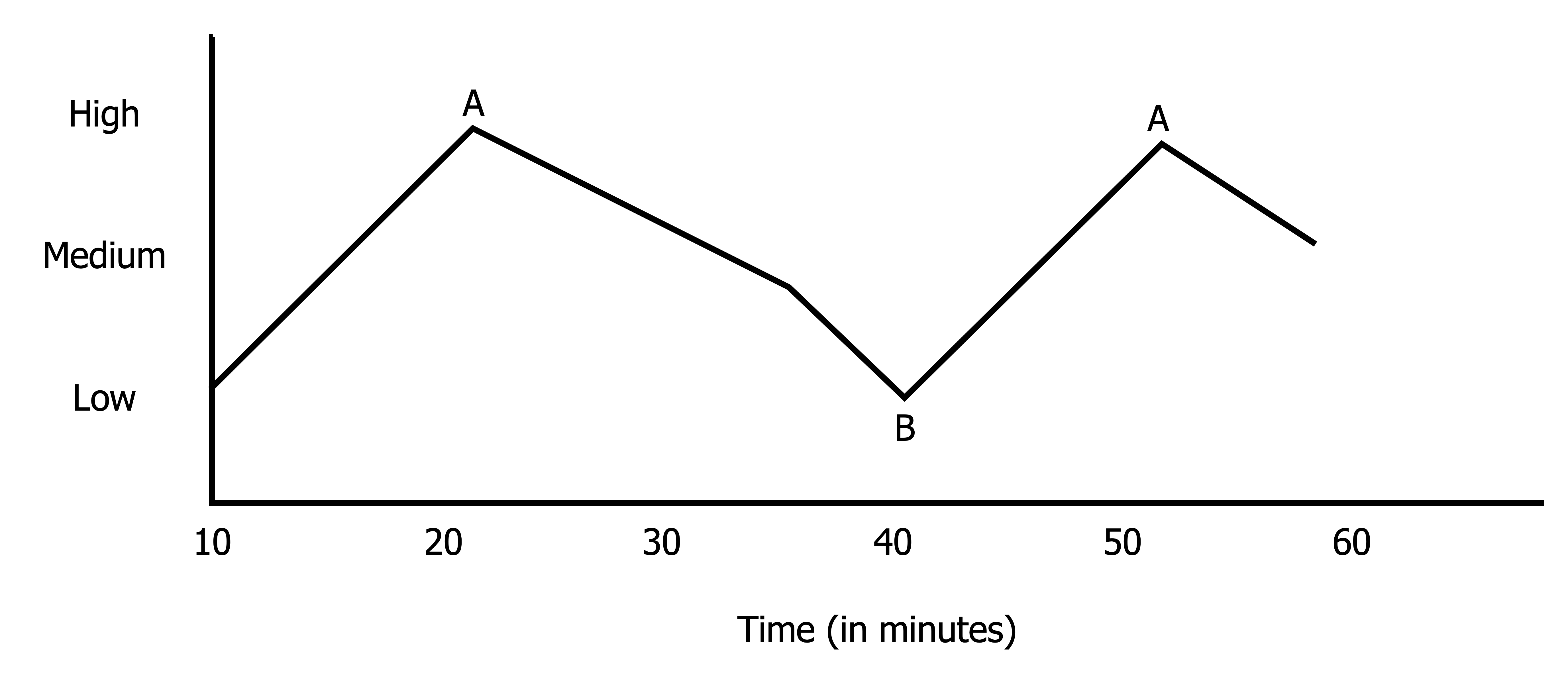

Something that is very important for teachers to realize is that they have a propensity to use volume, both loud and not loud, in cyclical patterns. By “cyclical” we mean that if someone charted the noise level in a classroom, it would probably look somewhat like Figure 8-1.

That is, it would increase to a certain threshold level (A), the teacher would act to quiet the class (B), then the cycle would recur. Teachers need to be sure that the time between high points on the curve does not become too short; otherwise, teachers get to the point that their control of unnecessary loudness is ineffective and they, in fact, spend essentially all of their time pleading for quiet.

Perhaps a word about the loudness of classrooms is in order. Teachers have to remind themselves that any room in the United States with twenty or so people in it will indeed have a certain level of noise present. This is true for living rooms, waiting rooms, church rooms, and even funeral rooms. Over time a group of people chat, fidget, cough, shuffle, and clear their throats. All of this contributes to the general noise level of the room. High school classrooms will not be silent places. The key for the teacher is to be able to distinguish between productive noise and disruptive noise. Patience and tolerance are required because adolescents cannot be quiet very long. Also, when students are excited about learning, such excitement will be manifested audibly. The prudent teacher senses when to reign-in the group without hassling them unduly.

Of course, teachers do not always need to rely on words, either softly or loudly spoken, to control student behavior. They can use actions or nonverbal communication to correct inappropriate behavior.

Use of Nonverbal Communication Techniques

There is a whole array of discipline strategies that are used consciously as well as unconsciously by most teachers. These strategies employ the use of nonverbal cues. Teachers should be more aware of the potential of nonverbal expressions as deterrents to undesirable student behavior. Nonverbal means the use of actions, facial expressions, or body language to convey specific messages to others.

Facial Expressions. Many teachers effectively use a number of types of looks to obtain the kind of student behavior they desire. Foremost among these special looks is the silent stare. Penetrating eyes can quickly defuse potential behavior problems. Remember, if one decides to use a stare, it is important to know when to stop—otherwise, it can deteriorate into a silly game. Frowns and raised eyebrows are also effective for expressing disapproval of a behavior.

Teachers also use nonverbal cues, such as snapping fingers, pointing, or folded arms, coupled with silence. However, teachers should also attend to the nonverbal expressions of students, for this second source of nonverbal language provides potent feedback to the teacher. It is present and must be recognized and interpreted. Otherwise, teacher and student will not communicate as fully as they should.

Silence. The adage, “Your action speaks so loud I can’t hear a word you say” holds true for teachers as much as for people in general. It may very well be that how we act as we seek appropriate discipline becomes more apparent than what we say. Many times desirable student behavior can be obtained by saying nothing. Indeed, a period of well-placed silence can be very effective. Students will generally continue the behavior for a short period of time but will soon realize something is wrong and indeed the silence will become a source of uncomfortableness. When becoming silent has the desired effect, nothing needs to be said. The teacher may proceed without comment. Here again, the length of the silence is critical for maximum effectiveness; too short and there will not be ample time for the students to process the cue and react to it. But too long a period of time encourages students to resume the inappropriate behavior. Practice is the best technique for realizing the most effective window of opportunity.

THE ROLE OF THE PARENT AND THE HOME IN PROMOTING ACCEPTABLE STUDENT BEHAVIOR

Without a doubt, the basis for what most educators would call appropriate discipline is the proper home environment. When students have been reared to behave properly and are punished by their parents or guardians if they do not, then the teacher has a real basis for securing appropriate behavior. When parents and teachers jointly seek to obtain the same goals and when both parties emphasize the same values, much more can be accomplished than when these two important parties in a child’s life work at cross-purposes. Unfortunately, the solid base of home support that was once widely enjoyed by agriculture teachers and others has deteriorated. Perhaps today’s teachers will have to work at cultivating that parental support that teachers were able to take for granted in past generations. The point is that this support is so valuable that it is worth the energy it takes to cultivate it. Teachers must realize that just because there are more broken homes and single parents today than ever in history, this does not mean there is less support for schooling. However, the existing support may be manifested differently. Educators must believe that the great majority of people care about their children’s proper growth and development.

The real key to securing home support in this area of promoting acceptable student behavior is for teachers to develop the appropriate relationships with the parents or guardians of their students. Teachers should initiate the development of this desired relationship. Fortunately, this does not even require additional work or time. Because teachers of agriculture are already visiting incoming and already-involved students, the development of a relationship of openness, trust, and commonality of goals with parents can be accomplished during these same visits.

Teachers must be willing to explain not only their program and the FFA activities to the parent(s) in the presence of the child but also to explain their expectations regarding student productivity and behavior. This should be accomplished during the very first home visit. Then if the parent or the child does not desire what the program consists of and what the teacher expects, they can elect another course that is more in keeping with their preferences.

When all aspects of schooling in the agriculture program have been presented and agreed on in the presence of the teacher, the parent(s), and the student, then the real foundation for promoting acceptable student behavior and performance has been laid. Certainly, during such home visits the prudent teacher will allow for and encourage the input of the parent(s) and child. Of course, the teacher does not act in a high-handed manner during such meetings. Rather, the teacher is a good public relations person and operates in a kind and humanistic fashion.

Once this parent-teacher relationship has been developed, build on it. When making future home visits let the parent(s) know of the student’s good efforts, positive accomplishments, and goals toward which to work. As long as the student is willing to respond effectively to the teacher’s efforts to secure appropriate behavior, the teacher need not involve the parent(s). Teachers should not tattle on the adolescent each time they are in touch with the parent(s). However, if, after repeated attempts to change a student’s behavior, the teacher has not been successful, then a visit with the parent(s) regarding the problem would be in order. In such cases the teacher and the parent(s) need to work jointly in deciding on the best course of action.

Teachers need to remember that parents are generally very proud and protective of their children. So do not approach parents suggesting that their Harry or Melanie is rotten to the core. Rather, approach them in a positive way, saying, “We all care about Melanie”; or “I need your help, ideas, and support.” Another caution that should be observed is that teachers should beware of ever threatening students that they are going to see their parent(s). Just as with all other discipline strategies, teachers do not threaten. Rather, when teachers have carefully decided the parent(s) need to be informed, they simply inform the student that this is their selected course of action. Otherwise the idea that the teacher will personally visit with a student’s parent(s) about a behavior problem will lose its potency.

Do not only use parents when there are problems. Teachers also should involve parents in the good times. Use them as chaperones at FFA activities and to assist with field trips, trips to career development events, and conventions. Parents do not lose their willingness to be involved with school activities just because their child has gone beyond the sixth grade. Secondary public school teachers simply have not done enough to capitalize on the vital link with the home that is initiated in the elementary years.

PROMOTING INDIVIDUAL RESPONSIBILITY FOR CONTROLLING BEHAVIOR

All of the previous discussions were aimed at helping students learn to behave in appropriate ways. One must not forget that students cannot always have teachers or others around to tell them what to do. A real challenge is to help students realize the need for and accept the challenge to become independent of the need for others to prompt them to behave appropriately. In a very real sense, teachers should have as a major goal helping their students become accustomed to being responsible for their own behavior. This necessitates discussing this goal and provides opportunities for students to accept more and more responsibility and then to be accountable for the results.

One technique, which can be used to help promote this individual responsibility for students’ actions, is to constantly relate the concept of responsibility to the expectations students will find in the industry they enter after graduation. Teachers should not only talk about industry’s insistence on each employee being responsible for his or her actions, but they should expose their students to their future type of work sites and let the students observe such expectations firsthand. Representatives from the industry periodically should be invited into the school classroom, where one of their themes will be to acquaint students with how the real world operates.

Students who plan to farm must realize early on that not putting forth energy because you are not in the mood will not lead to success. No one tolerates an employee or a partner who can only be depended on sporadically. Likewise, employers do not want workers who are undependable, unreliable, and tardy; cannot get along with their peers; and are unwilling to follow orders. Time after time employers stress that people do not lose their jobs because they cannot perform but because they cannot get along with others. Thus, in agriculture courses the issue is bigger than behaving in ways the teacher and school believe are appropriate. What teachers must really focus on is helping students learn how to behave successfully in life.

Teachers need to work to help students realize that in later life you either behave responsibly as an individual or you are made to behave by society through the laws society makes. Seize the opportunity to discuss current events in local communities as well as big time stories to help students discover the point that, as individuals, we are responsible for our actions and must accept that responsibility if society is to function. Rather than preaching to students, engage in meaningful dialogue. Another strategy for helping students learn the value of accepting responsibility for their actions is to involve civic leaders, law enforcement personnel, judicial personnel, and former juvenile delinquents in class discussions or FFA meetings. Teachers need reinforcement from others in society in their efforts to help students transfer learning from agricultural instruction to life in general.

In the case of promoting individual responsibility for controlling one’s own behavior, agriculture teachers need to be sure to use the same model for learning as it applies to discipline, which makes the study of agricultural subject matter career focused, that is, providing for the use of application. The best way to promote individual responsibility for controlling behavior is to give students ever-increasing amounts of responsibility for their own behavior as they progress through the agriculture program. In class they can be given more time to study independently in a self-directed mode. In lab they can be assigned increasingly complex tasks for which they are held responsible. The same strategy can be followed with respect to FFA activities. As students are increasingly allowed to direct their own activity, the teacher needs to remind them of what is happening. Positive reinforcement is essential, but so is corrective feedback at a one-on-one level.

SUMMARY

Successfully managing class behavior is a prerequisite to success in teaching. The actions of the teacher during the first few class sessions greatly influence the type of behavior exhibited in a class. A firm, fair beginning is needed. One cannot let behavior become a crisis and then expect to restore order. Order was lost because it could not be restored in the increments by which it was lost. Generally, it is absurd to think one can control a riot when one cannot individually control students who were unusual.

Once the atmosphere has been established, there are a number of techniques that can be used. One must remember, however, that the teacher and students must understand the problem and why it is a problem before it can be resolved. This demands communication. Communication is usually effective in an individual conference.

Other strategies for obtaining desirable behavior focus on the actions of the teacher well before the class. These include withholding recognition of undesirable behaviors, using suspense, using voice, and using nonverbal gestures.

Finally, the teacher must realize and accept the responsibility for being his or her own disciplinarian. Parents are the teacher’s best allies. The real goal is to have students accept the responsibility for directing their own behavior.

FOR FURTHER STUDY

- Visit a local agriculture department and observe how the teacher manages student behavior. Note what works and what does not work; then figure out why. Discuss your observations with the teacher.

- Discuss the basic requisites teachers must meet, in terms of pedagogy, if they hope to effectively manage their classrooms.

- Explain how to go about setting expectations regarding appropriate classroom and laboratory behavior.

- Give an example of the conditions under which the following discipline strategies should be used, and explain why: (a) individual conference, (b) withholding reinforcement.

- How can you best involve parents in classroom management? Outline a program that will result in a successful relationship between you as a teacher and the parents of your students.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 8.1: XY plot with time in minutes on the x-axis ranging from 10 to 60. y-axis labels are low (bottom), medium (middle), and high (top). Line appears in an M shape, with two peaks labeled A and trough in the middle labeled point B.

- Smith, Judith M., and Smith, Donald E. Child management. Champaign, IL: Research Press Company, 1976, p. 16. ↵