1 Factors Influencing Decisions About Teaching

POSITION AVAILABLE—TEACHER OF AGRICULTURE

Public school system needs teacher of agriculture with expertise in group and individualized instruction. Must be competent in teaching youth, adults, and students who are disadvantaged and handicapped. Knowledge of and the ability to apply principles of teaching and learning expected. Application of learning by students must be managed in the laboratory, in FFA organization activities, and in programs of supervised practice. Problem-solving teaching is expected. Teacher responsible for course of study development, lesson planning, and evaluation of student learning. Thorough understanding of agricultural education in the public schools a prerequisite. Preference to applicants committed to serve in a community as an agriculturalist and an educator. Submit resume to the Superintendent of Schools.

Being a teacher of agriculture in the public schools is challenging. One is responsible for much more than classroom and laboratory instruction. However, the primary task of any teacher is helping students learn. In the process of helping students learn, teachers plan, deliver, and evaluate instruction. The extent to which those who are taught acquire new knowledge, skills, and attitudes is determined primarily by two factors. The first is the expertise of teachers in the subject area. The second is their knowledge, understanding, and ability to put into practice what is known about teaching and learning. Prospective and practicing teachers of agriculture need to develop further their competence to plan, deliver, and evaluate instruction. Reading, study, and instruction about methods of teaching agriculture can provide that competence.

OBJECTIVES

Effective teachers consider several factors when making decisions about teaching techniques and strategies. Teaching does not take place in a vacuum. After reading this chapter, you will be able to make decisions about instruction within a context that includes

- The purposes and objectives to be achieved through the instructional program; in this case, the purposes of public school education in agriculture.

- The clientele taught—their interests, aspirations, experiences, and characteristics.

- The organization and content of the subject matter.

- The psychology of learning—what is known about some basic principles of teaching and learning.

- The knowledge and skill of the teacher not only in the subject matter but also in planning, delivering, and evaluating instruction.

INTERRELATIONSHIP OF THE FIVE FACTORS

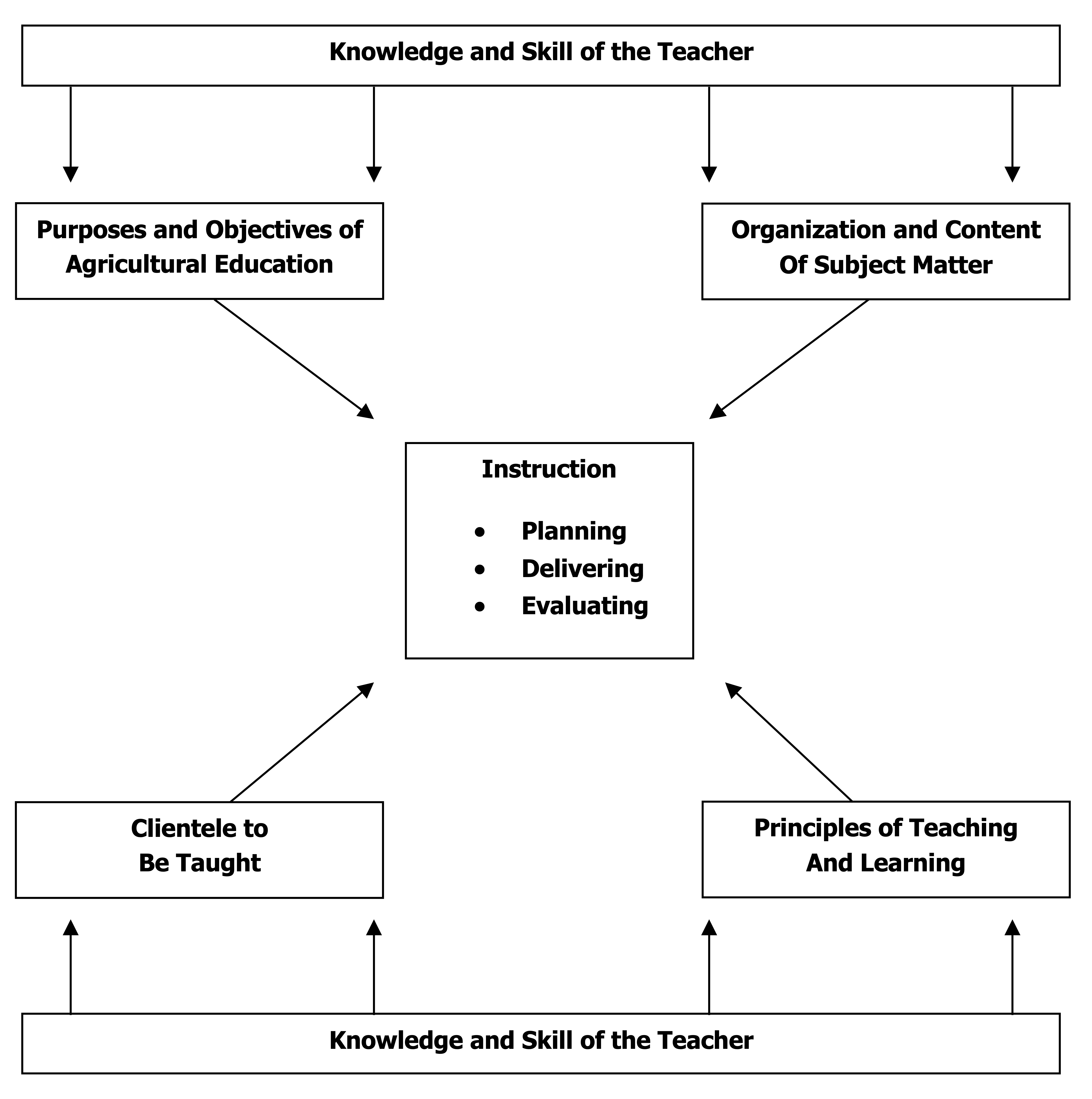

Thoughtful consideration of the factors influencing decisions about instruction indicated in Figure 1-1 reveals two important ideas. First, it is clear that the five factors, while influencing instructional strategies and techniques directly, are interrelated and mutually interdependent. Purposes and objectives of instructional programs are not derived in isolation from the clientele who are to be taught. Likewise, purposes and objectives influence directly the subject matter or content that will be taught. Knowledge of the principles of teaching and learning indicates how subject matter is best organized to optimize learning. In a similar manner, characteristics of learners influence decisions about teaching techniques.

A second important idea that becomes evident when the five factors influencing decisions about teaching are considered is that in any particular teaching situation, four of the five factors are relatively fixed. In real situations teachers are confronted with clearly defined instructional programs designed to achieve stated objectives for a specifically identified clientele at a particular time. In addition, the storehouse of what is known about teaching and learning at a given time is relatively stable. Consequently, the factor influencing decision making about instruction that is most flexible and potentially responsive to change is the knowledge and skill of the teacher.

A basic idea undergirds this book: A teacher’s knowledge and skills, both in the content to be taught and in the psychology of teaching and learning, have a major influence on instructional decision making and, in turn, on learning outcomes. Each chapter is designed to instruct teachers of agriculture and those preparing to teach agriculture in the fundamental theory and the important principles of teaching and learning. Each chapter describes and illustrates how teachers can apply these understandings in planning, delivering, and evaluating instruction. The focus of this chapter is to describe how the objectives of instructional programs, clientele to be taught, subject matter, and the psychology of teaching and learning influence decisions teachers must make about instruction in order for students to achieve high levels of competence.

PUBLIC SCHOOL EDUCATION IN AGRICULTURE

Agricultural subject matter is taught at all levels in the public schools, from kindergarten to the university level. In kindergarten and the elementary grades, agricultural instruction includes animals and plants; nutrition and food; and how people live, work, and play. Outdoor educational activities in elementary schools involve agriculture and conservation of natural resources. Agriculture as a specific course or an identifiable unit of instruction in other courses appears sometimes in middle school, but courses in agriculture are most often offered at the senior high school level; in postsecondary schools, technical institutes, and community colleges; in colleges and universities; and in adult and continuing education programs offered by high schools and postsecondary schools and colleges.

Objectives of Instruction in Agriculture

Instruction pertaining to agricultural topics, as well as specifically identified courses in agriculture, contribute to the attainment of a number of objectives. These objectives vary depending on the level at which instruction is provided and the persons for whom the instruction is offered. It is important for teachers of agriculture to be aware of and understand the range of objectives for educational programs to which agricultural instruction contributes. Few if any agricultural education programs are designed to emphasize equally all of the objectives for agricultural education discussed in this section. Usually, specific agricultural education programs are designed primarily to accomplish one of the objectives described; however, teachers need to be alert to the fact that a particular agriculture course or unit of instruction designed to accomplish a specific objective may, for some students, contribute to the attainment of other equally important, meaningful objectives.

Provide Instruction about Agriculture—Agricultural Literacy. The agricultural industry—the production of food and fiber and the related complex of agribusiness and industry—is an essential and important part of the economic, political, and social concerns of the nation and the world. Persons who are knowledgeable about the community, state, and nation in which they live must have some appreciation for and knowledge and understanding about the role of agriculture in their lives. One purpose of instruction in agriculture is to develop knowledge and skills that contribute to the general education and avocational interests of persons who are not or will not be occupationally engaged in the agricultural industry.

The Committee on Agricultural Education in Secondary Schools appointed by the National Academy of Sciences concluded that instruction about agriculture should be offered to all students, regardless of their career goals or whether they are urban, suburban, or rural.[1] A major goal stated in The National Strategic Plan and Action Agenda for Agricultural Education[2] is “All students conversationally literate in agriculture, food, fiber and natural resources systems.” Specifically, instruction about agriculture contributes to

- Understanding and appreciation of agriculture for the welfare of all; the interrelationships between agriculture and other aspects of business and commerce; the contribution of agriculture to world trade; and the interrelationships between rural and urban people.

- Understanding and appreciation of the complex processes of food production, processing, and distribution, and the cost of food acquired at each step of the process.

- Awareness of the responsibilities of all citizens in influencing public policies that affect agriculture.

- Familiarization and appreciation of the history of agriculture and rural life, the advances made in agriculture and their impact on all citizens, the values of rural people, and the literature, art, and music that give insight into our rural heritage.

- Knowledge of nutrition that leads to informed choices about diet and health.

- Knowledge and attitudes needed to care for the environment.

- Practical knowledge and skills useful in engaging in avocational interests such as landscaping, conserving natural resources, raising food, performing mechanical skills, and using open spaces in urban areas as well as rural areas for leisure activities.

Instruction about agriculture that has as its major objective the development of avocational and practical arts knowledge and skill is most applicable for students in school and adults who are not engaged in an agricultural occupation. In many cases, subject matter pertaining to agriculture is taught in the elementary grades and in general agriculture and practical arts courses taught in junior high schools and in some senior high schools. Examples of long-standing practical arts programs in agriculture include the school gardening program in the Cleveland Public Schools and the elementary and junior high school agricultural education programs in the Los Angeles School District. Instruction offered by high schools and community colleges as regular or continuing education courses in landscaping, floriculture, lawn care, and mechanical skills for those not engaged in an agricultural occupation are exam pies of instruction designed primarily to develop avocational and practical arts knowledge and skill in agriculture.

Frequently, instruction about agriculture that is designed to achieve agricultural literacy objectives is offered by elementary school teachers and teachers of other courses in the school rather than by persons whose teaching specialty is agriculture. When this is the case, teachers of agriculture in these schools have an opportunity and a responsibility to provide consultative assistance to other teachers who teach about agriculture and involve students in school activities concerning agriculture and rural life. In some middle schools, and to a lesser extent in senior high schools, teachers who are specialists in agriculture are employed to teach quarter-, semester-, or year-long practical arts courses in agriculture.

Provide Exploration of and Orientation to Occupations Requiring Knowledge and Skill in Agriculture. Specialists in the psychology of occupational and career development indicate that the choice of vocation is one of the major concerns of adolescents, particularly as they proceed from early to late adolescence. Emancipation from parents and the home, attainment of economic self-sufficiency, and recognition as an adult are achieved largely through successfully selecting, preparing for, and becoming established in an occupation.

Occupational decision making is a process, not an event. Many factors, including awareness of and knowledge about occupations, are involved as people make occupational and career decisions. Vocation choice is based on the occupations of which a person is aware. There is evidence that occupational choices are made in terms of what people know about themselves and what they know about the world of work. Emotional needs influence the occupation choice process; however, knowledge about occupational areas and specific jobs is also important. Actual work experience is crucial for the reality testing that is a part of the occupational choice process.

Instruction in and about agriculture, particularly for adolescents and preadolescents, must have as one of its objectives the provision of information and experiences about occupations involving knowledge and skill in agriculture, the type of preparation needed for entry and progress in these occupations, the attributes of those who are successful in these occupations, and the outlook for employment or self-employment and advancement. Agricultural education programs that emphasize occupational exploration and orientation, if this objective is to be achieved, must provide opportunities for students to participate in actual work experiences. For middle school students and some older adolescents this reality testing in the world of work begins with observational experience on farms and in agribusiness firms (e.g., veterinarian offices, landscaping firms, meat processing plants, or farm lending agencies). To be most effective, instruction designed to teach about the world of work must, if at all possible, provide actual work experience in one or more agricultural occupations. Instructional programs designed to emphasize occupational exploration and orientation provide students with information about and experience in a variety of occupations rather than specialized information and extensive experience in one job or occupational area.

Develop Knowledge and Skill for Occupational Competence. Occupational proficiency—preparation for and advancement in the world of work—is stated frequently as the major objective of agricultural education in the public schools. Much of the agricultural instruction offered in secondary and postsecondary public schools in the United States has as its major objective occupational competence. Agricultural education programs in secondary and postsecondary schools are financed in part by federal and state funds earmarked for occupational education in addition to local funds allocated for the support of public schools.

The Committee on Agricultural Education in Secondary Schools of the National Academy of Sciences[3] recommended that instruction in agriculture designed primarily to develop occupational competence be upgraded to prepare students more effectively for careers in agricultural science, agribusiness, marketing, management, and food production and processing. The National Strategic Plan and Action Agenda for Agricultural Education[4] lists the following specific objectives for occupational competency in agriculture.

- Students must be prepared for successful careers in global agriculture, food, fiber, and natural resources systems.

- Every agriculture student must have opportunities for experiential learning and leadership development.

These objectives for public school education in agriculture emphasize the development of occupational competence; however, the objectives also recognize the importance of general education—namely leadership—for occupational competence and success.

Prepare for Advanced Study of Agriculture. An objective of agricultural education programs is to prepare those enrolled for more advanced study of agriculture. For example, instruction in agriculture at the high school level may be designed to prepare graduates for the study of agriculture in postsecondary technical institutes and community colleges or in four-year colleges and universities. Postsecondary agricultural education programs also prepare students for further study of agriculture at the university level.

Agriculture courses of this type offered in community colleges are usually described as transfer courses, indicating that the courses are intended to transfer to a four-year college or university for credit toward a baccalaureate degree. Agriculture instruction offered at the secondary and postsecondary levels with the primary objective of occupational competence also allows students to learn about the opportunities and needs for advanced study in agriculture. In these cases, an agricultural education program designed primarily to achieve an occupational competence objective may simultaneously contribute to the preparation of students for advanced study of agriculture.

Agricultural Education as a Part of Public Education

Agricultural education programs in the public schools are designed to accomplish educational objectives that pertain specifically to acquiring appreciation, understanding, knowledge, and skills applicable to the agricultural sciences, agribusiness, and the production and processing of food and fiber. It is also important that agricultural education programs be designed and conducted such that instruction in and about agriculture contributes to the achievement of all purposes of the school. In addition to the career and occupational development of students, public education is concerned with the students’ intellectual, social, and cultural development. Instruction in and about agriculture can contribute to other purposes of public education without neglecting a major commitment to achieving specific agricultural education objectives.

Teachers of agriculture must be aware that skills necessary for occupational success include the abilities to read, write, speak, and listen; competence in using numbers; and the ability to work cooperatively and harmoniously with others. These skills are taught in what is usually referred to as general education subjects in the public schools. Teachers of agriculture need to realize that instruction in agriculture also can contribute to the attainment of these skills.

Teachers of agriculture can assist in relating instruction in agriculture more closely with the rest of the school’s program in two ways. First, teachers, through their comments and actions, can communicate directly and indirectly to students that what they are studying in English, mathematics, science, and the other core courses is relevant to their interests and goals. Second, teachers of agriculture must make it evident that instruction in agriculture contributes directly to the attainment of general skills relevant to communication, computation, problem solving and decision making, human relations, and leadership. Teachers of agriculture must make a conscious and deliberate effort to maximize this contribution of agricultural education to the overall objectives of the school. Effective teachers of agriculture make important contributions to the understanding and use of the social sciences, mathematics, biological and natural sciences, and English. Agriculture is an applied science, so it is not unreasonable to expect that some of the best teaching of science will be done in courses in agriculture. One of the basic premises of The National FFA Organization is the development of some very important general education attitudes and skills, particularly citizenship and leadership abilities.

Too often agricultural education is regarded primarily as a function of a department of the school, not as a function of the total school system. Teachers of agriculture need to plan and conduct instructional programs such that agricultural education, while achieving specific and unique objectives related to agriculture, is an integral part of the school system. It is also important that teachers use instructional techniques and strategies that make it possible for instruction in agriculture to contribute directly and substantially to all purposes of the school.

Clientele in Agricultural Education

There is a high degree of interdependence among educational objectives for a particular agricultural education program, the content and organization of the educational program, and the clientele who enroll in the instructional program. Not only are agricultural education programs designed to accomplish one or more educational objectives but the programs are also designed for specific clientele. Agricultural education is provided to students enrolled in public schools and adults and youth who have completed or left school. Clientele receiving instruction in and about agriculture range from kindergarten and elementary school students enrolled in agricultural literacy programs to secondary and postsecondary school students enrolled in courses that emphasize occupational competence and preparation for advanced study. Also, out-of-school youth and adults enroll in continuing education programs in agriculture to enhance their knowledge and skill.

Subject Matter for Instruction in and about Agriculture

The subject matter taught in agricultural education programs is broad and diverse. The National Science Foundation’s Committee on Agricultural Education defined the agricultural sector as including “supply and service functions involving agricultural inputs; production of agricultural commodities; processing and distribution of agricultural products; use, conservation, development and management of air, land, and water resources; development and maintenance of rural recreational and aesthetic resources; and related economic, sociological, political, environmental, and behavior functions.”[5]

The National Academy of Sciences’s Committee on Agricultural Education in Secondary Schools[6] defined instruction in and about agriculture as including basic concepts and knowledge about

- Production of agricultural commodities, including food, fiber, wood products, horticultural crops, and other plant and animal products;

- Financing, processing, marketing, and distribution of agricultural products;

- Farm production supply and service industries;

- Use and conservation of land and water resources;

- Development and maintenance of recreational resources; and

- Related economic, sociological, political, environmental, and cultural characteristics of the food and fiber system.

The subject matter taught in agricultural education programs in public schools includes the following specialized areas of content:

- Agricultural literacy

- Agricultural science

- Agricultural production

- Agribusiness supplies and services

- Agricultural mechanics and engineering

- Agricultural processing and marketing

- Horticulture

- Aquaculture

- Agricultural and natural resources conservation

- Forestry

Dimensions of a Complete Program of Agricultural Instruction

Classroom Instruction. The core of a successful agricultural education program is formal instruction in the school. Thorough and expert classroom instruction sets standards for all phases of the instructional program and determines to a considerable extent what out-of-classroom or out-of-school activities will be conducted. Instruction in the classroom involves not only group instruction but also individual instruction and supervision. Expert classroom instruction begins with a well-planned, relevant course of study, which is discussed in Chapter 3. Formal instruction that results in high levels of achievement by students requires also that teachers creatively use group and individualized teaching techniques, which are described in Chapters 6 and 7.

Application of Learning. Instruction that results in maximum achievement by students includes techniques and activities that allow students to apply what is taught in the classroom in real or laboratory situations. To be most effective, application of learning must be supervised by the teacher and be accompanied by additional instruction to ensure that what is taught is not only understood but is useful to students. There are three primary systems for providing opportunities for students to combine classroom instruction with the application of what is taught—the school laboratory, supervised agricultural experiences, and the FFA, the student organization. In Part III, Chapters 9, 10, and 11 deal with these three approaches for making what is taught practical and useful.

The School Laboratory. Laboratory instruction is an essential complement to classroom instruction if students are to achieve the highest levels of competence. It is virtually impossible to teach agriculture adequately without laboratories provided by the school. School laboratory facilities most needed for instruction in agriculture include specialized laboratories directly related to the specific areas of instruction. Access to a computer laboratory is essential. Production agriculture programs require a land laboratory; biotechnology instruction must be accompanied by laboratory experience in a properly equipped facility; greenhouses and plant growth areas are required for ornamental horticulture programs; a laboratory adequately equipped for engine analysis, repair, and operation is essential for agricultural mechanics programs. Other school laboratories might include, but are not limited to, forests, nature trails, wetlands, ponds, aquaculture facilities, putting greens and fairways, barns, hydroponics facilities, wildlife habitats, or computer labs.

Supervised Experience. Instruction that emphasizes the development of occupational competence offered in secondary and postsecondary schools places primary emphasis on the development of knowledge and skill needed for entry and advancement in the world of work. Laboratory instruction in programs of this type, is instruction and supervision in the actual careers that students are preparing to enter. For students enrolled in production agriculture programs, a farm or ranch becomes the location for supervised agricultural experience. Such experience in nonfarm agribusiness and industrial firms is essential for students enrolled in other specialized areas such as agricultural mechanics, agricultural business and supplies, ornamental horticulture, and agricultural products. For students enrolled in agricultural science programs, a university, private laboratory, or local research firm becomes the location for supervised agricultural experience.

FFA. The organization for students enrolled in instructional programs in agriculture is a laboratory for acquiring and applying knowledge and skill in leadership, citizenship, and career success. FFA is an integral part of the total agricultural education program and contributes best to the attainment of the objectives of agricultural education and the school when the organization and its activities are developed as laboratory activities that are a part of well-planned and delivered instruction in agriculture.

Use of Community Resources. Well-organized and conducted agricultural education programs are community oriented. Instruction takes place in the community as well as in the school. In-school classroom and laboratory instruction is most realistic and interesting when it reflects the agriculture and agribusiness in the community. Persons as well as the physical facilities in the community are resources useful in teaching. In effect, the community is a laboratory for the instructional program. Involvement of persons and facilities in the community in planning and conducting instructional programs has two major advantages. First, the involvement of resource persons as consultants and teachers as well as the use of the facilities of the community makes instruction relevant and real, and thereby more interesting and meaningful to students. Second, a high degree of involvement by persons in the community is an excellent way for them to get firsthand information about what goes on in school generally as well as specific information about the agricultural education program.

Facilities and Organizations. Some of the most valuable community resources that contribute to successful agricultural education programs are business and industrial firms, farms, parks, recreational areas, governmental agencies serving the agricultural sector, and organizations that relate to agriculture. These community resources in many cases supply the actual subject matter taught. For example, topics such as the organization and operation of agribusiness firms, farm management, career opportunities in agriculture, and qualifications and requirements for employment in agricultural occupations are best taught through actual case examples and, if possible, with actual contact with both the facilities and the persons owning, managing, and working in the various farm and agribusiness firms and organizations. Community facilities are used effectively as sites for field trips and as training stations for students’ supervised agricultural experiences. Community facilities and the persons associated with them provide excellent opportunities for independent study activities for students.

People in the Community. People living and working in the community provide a rich resource of specialized knowledge and skills to contribute to an effective instructional program. The use of experts as resource people is a teaching technique that has advantages both to teachers and to students. People in the community who have high levels of expertise in the subjects being taught readily respond to opportunities to assist with classroom and laboratory instruction, to instruct students during field trips, and to consult with students who are conducting independent studies or class assignments. Farmers, extension educators, and employees in agribusiness firms provide on-the-job supervision and instruction to students who are placed on farms and in agribusinesses for supervised agricultural experience. FFA alumni can be of assistance to the teacher. The appropriate use of resource people in teaching agriculture ensures that up-to-date information is being delivered and that technically correct skills are being taught. Resource people, therefore, provide excellent opportunities to update and expand the knowledge and skill level of teachers of agriculture.

Advisory Committees. A practice that has proven effective for making the expertise of people in the community available to teachers and the school is the formation of a school-sponsored advisory committee for agricultural education. Properly organized and appropriately used advisory committees contribute much to planning, conducting, and evaluating instruction in agriculture. It is important that the school administration and the school’s governing board approve policies for the formation and use of the advisory committee. Teachers must be skilled in using advisory committees in an advisory and consultative capacity. These committees play an important role in linking the school and the community; they offer advice about the objectives the program should strive to achieve, about the clientele to be served, about the programs that contribute most directly to the accomplishment of objectives, and about the extent to which objectives have been accomplished. Advisory committees are a means whereby accurate information about the school and the agricultural education program is communicated to persons in the community. Teachers who direct agricultural education programs that are community oriented and contribute best to the acquisition of knowledge and skill by those enrolled have an organized and functioning advisory committee as a part of a complete program of agricultural education.

Parents. In addition to school-community cooperative efforts, effective and successful agricultural education programs require cooperative and mutually supportive relationships among teachers, students, and parents or guardians. It is essential that teachers take the initiative in informing parents about the agricultural education program and activities, in communicating to parents what the expectations are for students enrolled, and in involving parents in appropriate activities when that involvement contributes directly to effective teaching and learning. Parents supervise the agricultural experience activities of students when students’ places of employment are the home farms or the agribusinesses owned by the parents. Highly competent teachers put high priority on knowing personally the parents of students and having firsthand knowledge of students’ home situations. This direct knowledge of students, their parents, and the situations in which they live and work can best be obtained by teachers visiting the homes and workplaces of students. Students’ backgrounds, their interests and motivations, and their parents’ support and aspirations for them is vital information for teachers who make decisions about instruction that results in students attaining a high level of knowledge and skill in agriculture.

Teachers and Administrators in the School. Earlier in this chapter the point was made that agricultural education programs contribute directly to all purposes and objectives of the school. Also it was proposed that the general education and other specialized courses taken by students enrolled in agriculture contribute to the achievement of specific objectives in agriculture classes. The interrelatedness of instruction in and about agriculture with the total instructional program in the school is real and visible when teachers of agriculture make conscious and deliberate efforts to work cooperatively with administrators, teachers, and counselors in the school. It is imperative that agriculture teachers conduct programs in a manner that makes it evident that school administrators have the same degree of administrative and supervisory responsibilities for the agricultural education program as they do for other programs in the school. Teachers of agriculture must be aware of and follow school policies pertaining to the discipline of students, absence from school for field trips and supervised experience, use of school laboratories to provide products and services to the community, and all other matters that in some way differentiate agricultural education from other programs in the school. Informing administrators about the agricultural education program and the accomplishments of students is necessary. However, teachers of agriculture must ensure that school administrators are actively involved in all aspects of the program so that they consider instruction in agriculture a viable and important part of the school’s program and activities.

Successful teachers of agriculture keep other teachers and other professional personnel, such as guidance counselors, informed about all aspects of the agricultural education program. Information about the agricultural education program does not automatically get communicated to other professional personnel in the school. Teachers should use every opportunity not only to provide information about the school’s agricultural education program but also to involve teachers, counselors, and administrators in appropriate roles, such as consultants on special topics, advisors for student activities, and guests at special functions such as the annual FFA banquet. Teachers of agriculture, if they expect other teachers and professional personnel in the school to know about and take interest in the agricultural education program, must make deliberate efforts to acquire firsthand information about what is taught in other courses in the school so that the importance and relevance of these courses to agriculture can be emphasized. It is important that teachers of agriculture confer with other professionals in the school about mutual concerns that relate to all facets of a student’s educational experiences. Teachers of agriculture who operate as contributing and cooperative members of a school’s faculty accomplish much in demonstrating that agricultural education is an important part of the school, not exclusively the function of one department in the school.

ORGANIZATION AND CONTENT OF SUBJECT MATTER

Another factor influencing decisions teachers make about planning, delivering, and evaluating instruction is the organization and content of the subject matter. (See Figure 1-1.) For example, different instructional techniques are required for teaching facts about the agricultural industry in the community, for teaching welding skills, for teaching the application of principles of plant growth, or for teaching affective attributes such as working cooperatively with others. What is to be taught and how that subject matter is structured and organized are important in determining how instruction can be provided in the most realistic, interesting, and effective manner.

A review of the factors influencing decisions about teaching indicated in Figure 1-1 reinforces the interrelatedness among objectives, subject matter, clientele, and the psychology of learning. By now it should be clear that the purposes and objectives of the agricultural education program determine to a considerable extent the subject matter that will be taught. What is known about how people learn—the principles of teaching and learning—has direct and important implications for how the subject matter should be organized and structured to facilitate most advantageously the teaching-learning process. This point is highlighted in Chapter 2, which discusses some of the major principles of teaching and learning that concern the organization and content of subject matter. Some characteristics of those who are to be taught—the clientele—play a decisive role not only in defining the subject matter that must be taught but also in directing the sequence in which units of instruction are taught most beneficially.

Organizing and structuring subject matter is a basic concern of planning the course of study. Chapter 3, “Planning the Course of Study,” provides instruction and examples relating to determining course content and to organizing and sequencing subject matter such that instruction is meaningful to students and results in high levels of achievement by those who successfully complete the instructional program.

CHARACTERISTICS AND INTERESTS OF CLIENTELE

The characteristics, interests, and aspirations of those taught, whether high school students or adults, are potent factors influencing decisions about instruction. The interests and aspirations of students and their families, students’ backgrounds and previous levels of success in school, prior experiences and instruction related to the subject matter, and academic attributes and study skills must influence the planning, delivery, and evaluation of instruction if maximum levels of competence are to be achieved.

The direct association between the purposes and objectives of a particular agricultural education program and the clientele the program serves has been emphasized previously. Almost without exception, a specific course designed to accomplish certain objectives can be directed toward a specific clientele group possessing distinctive characteristics that have direct and significant implications for instructional strategies and techniques. Expert teachers make special efforts to understand the unique characteristics of their students and to be aware of students’ interests, aspirations, and motivating forces. Understanding students and what motivates them in concert with a mastery of the basic principles of teaching and learning equips teachers with the ability to plan for and provide instruction that accomplishes efficiently and effectively the learning outcomes sought.

Characteristics of learners influence directly the selection and use of instructional techniques. Even though a specific course is designed for an identifiable group of persons with similar characteristics, teachers need to be alert to diversity within the group. Groups that appear to be relatively homogeneous for certain characteristics frequently display a great deal of diversity and variation in background, interest, prior instruction and experience, learning style, and academic skills. It is the diversity within a group that must be recognized and addressed if instructional techniques are to reflect a real concern for individual needs and interests.

Interests and Aspirations

Psychologists have identified some major social and personality needs that motivate individuals in addition to the physical needs for food, drink, and sex. The social and personality needs that motivate learners include the needs for status, security, affection, independence, and achievement. The adolescent’s needs for status and independence are particularly important. Activities and experiences that are a part of or accompany agricultural education courses and programs will be sought by persons who perceive instruction in agriculture as an effective means for fulfilling these social and personality needs, especially the need for status, independence, and achievement. When high school students enrolled in agricultural education programs are asked to name the most important reasons for enrolling, their responses indicate clearly that they believe instruction in agriculture will contribute to the attainment of a variety of their goals and objectives.

Following are the responses of some high school students enrolled in agricultural education courses to the question “Why did you enroll in agricultural education?”[7]

Occupational Orientation and Exploration. “I enrolled in agricultural mechanics because I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do, and now I find I like mechanics pretty well.” “So I can think about what I want to do in life—work or go to college.”

Preparation for Further Schooling. A student in agricultural mechanics plans “on going to technical school to further my education.” Another student studying animal science believes “it would help me in my future career which is becoming a veterinarian.”

Preparation for Employment or Self-Employment. “I want to manage a farm so I can stay on the farm for a living.”

Practical Arts Knowledge and Skill. A ninth-grade student elected agricultural education “because I am interested in agriculture.” A student in an environmental science course “enrolled to learn all I can about the pollution problem. and wildlife. This course helps me understand what I and others will face in the future.”

Independence—Status—Achievement. “Need money” was the way an eleventh-grade student expressed the reason for enrolling in an agricultural business program that included on-the-job supervised agricultural experience. “I love flowers. I have a certain feeling of pride in myself when they are in bloom and people buy them. This course is a great opportunity for me to really understand the basics of floriculture.”

Highly competent teachers of agriculture are aware of the motivating forces behind students’ decisions to enroll in agriculture courses. The students’ motivations provide a base for making instruction interesting and useful.

Background and Home Environment

Parents or guardians, as well as students and teachers, are important in shaping the interests and goals of adolescents. Teachers of high school courses in agriculture find it important to know what aspirations parents hold for their daughters and sons. The attitudes displayed in the home about school in general, frequency of attendance, level of achievement expected, and the perceived value of instruction in agriculture play an important role in influencing students’ behaviors and attitudes. Parents’ level of education, occupational status, and income are important factors that have profound influence on how students value schooling, as well as determining the resources available for assisting students in achieving their goals and participating in activities that are an integral part of instruction. For example, a student from a family with limited financial resources can hardly be expected to provide the materials for constructing an agricultural mechanics project required as a part of laboratory instruction. Likewise, it is difficult for students who must work part time to help support a family to demonstrate a high level of interest and enthusiasm for learning about and participating in FFA leadership activities that take place primarily during after-school hours.

Experience Related to the Subject Matter

Careful attention must be given to the previous experience students have concerning what is being taught and whether students are participating concurrently with instruction in work or supervised agricultural experiences. The extent of students’ work experience involving the subject matter is important. Equally important is the type of work or occupational experience students bring to the instructional setting. Students who are working or have worked independently in situations in which they make decisions bring to the classroom or laboratory different insights and skills than do students whose experience is primarily observing and assisting others. Students who already possess specialized knowledge and skills in certain aspects of the subject matter can be used effectively as resource persons for the entire class or as tutors or coaches for other persons in the group. Experience of those enrolled in an adult education program is a major factor in selecting teaching techniques most appropriate for adults in contrast to teaching techniques most appropriate for high school students.

Previous Instruction

Teachers who are in the best position to make instructional decisions that contribute to students achieving high levels of competence also discover and attend to the previous instruction of students in agriculture and other courses that are closely related, particularly science and mathematics. Students who have completed ninth- and tenth-grade courses in agriculture prior to enrolling in an ornamental horticulture course in the eleventh grade can be taught differently from other students in the course who have no prior instruction in agriculture. Teachers of agriculture need to be alert to what is being taught about agriculture to students in other subjects in the school. If agriculture teachers are knowledgeable about what is taught in science and mathematics courses, for example, they can reinforce this knowledge and skill by demonstrating its application and use in their agricultural instruction.

Academic Attributes—Success in School

Learners, whether high school students or adults, vary not only in their interests and motivations for learning but also in intellectual skills and attributes that are associated closely with success in school. Intellectual ability, usually described as level of intelligence, is a major factor that is for most students closely associated with achievement. Other important attributes include reading level, the ability to reason and solve problems, and the determination and desire to stay with a task in order to achieve a high level of competence. It is important that teachers have accurate knowledge of their students’ intellectual and academic attributes if appropriate teaching strategies are to be used. For example, students who cannot or will not read can be expected to demonstrate only meager achievement if printed material is the only resource students use to acquire new knowledge.

Students’ enthusiasm for school in general and for specific courses is influenced strongly by the success they experience. This factor should be considered by teachers as they plan and teach. Instructional strategies need to be devised that ensure, wherever possible, that all students experience some degree of success in learning and that successful achievement is recognized and rewarded. In some cases it will be necessary for teachers to make special efforts to communicate to students and prospective students that the instructional strategies and techniques will, in fact, be different from what they have experienced in the past. For example, dropouts who experienced limited success in school may show little enthusiasm for a proposed course unless it is made clear to them how the new course will allow them to succeed in acquiring skills and knowledge they believe are important.

Study Skills

Too often teachers overlook the fact that students as well as teachers need to be adept in the teaching strategies and techniques used. Successful teachers make sure that learners are active participants in the teaching-learning process. Students, to be active learners, must have both the desire and the requisite study skills for active participation in the various techniques and activities employed by the teacher. The following illustrations emphasize this point. Instructional techniques requiring students to use books, magazines, and other publications as resource materials are not efficient or effective unless students know how to use an index or table of contents to locate relevant sections of a publication. Students with limited knowledge, skill, or experience in using computers are at a disadvantage in using the Internet and other electronic media. Independent study as a technique of instruction results not only in meager achievement but also in a frustrated learner unless students have been taught skills that are necessary for independent study, such as how to identify and state problems and questions, how to locate and use appropriate resources, how to evaluate information and opinions, how to formulate and test conclusions, and how to report the results of the study orally or in writing.

PRINCIPLES OF TEACHING AND LEARNING

Knowledge and understanding of the psychology of learning are basic to making decisions about and using appropriate instructional strategies and techniques. Some understanding by the teacher of the conditions that stimulate learning and how learning takes place is essential if instruction is to result in a high level of competence achieved by those who are taught. Teachers who are familiar with and understand the basic tenets of how people learn have the capacity to create innovative teaching techniques and use instructional media that are most appropriate to achieve the learning outcomes sought. Teachers who understand how learning takes place possess the ability both to diagnose problems encountered in teaching and to prescribe techniques and strategies that improve the teaching-learning process.

Fundamental to what is being taught through this book is the indispensable and direct connection between the practice of teaching and the psychology of learning. Each chapter is undergirded by the basic premise that teacher behaviors of planning, delivering, and evaluating instruction must be grounded firmly in what is known about how people learn.

Teaching and Learning

Teaching is best described as guiding and directing the learning process such that learners acquire new knowledge, skills, or attitudes; increase their enthusiasm for learning; and develop further their skills.

One psychologist describes teaching this way.[8]

There is no such operation as teaching in and of itself. No one can teach anyone anything; he [sic] can only arrange conditions whereby a learner might learn. Among such conditions are showing and telling, but whether or not learning goes on depends more on the learner than the teacher.

This description of teaching makes it clear that the learner, as well as the teacher, plays a central role in the teaching-learning process. In this context learning is usually described as a process by which persons, through their own activity, become changed in behavior. An essential element of learning is that unless the learner processes the subject matter being studied in a meaningful and understandable manner, little will be learned or retained. Bender and Boucher describe learning as follows.

When a person learns, s/he feels, thinks, and acts differently because his or her interests, skills, abilities, understandings, attitudes and appreciations have been changed …. It is important to understand that learning is a self-active, personal, choice making process. A person learns what he or she wants to learn.[9]

Principles of Learning

In Chapter 2 learning theory and research substantiate some of the basic principles of learning. The connection between the principles of learning and the practice of teaching is illustrated by describing teacher behaviors that exemplify how the principles of learning are translated into teaching practice. Principles of learning will be presented that pertain to:

- The organization and structure of subject matter

- Motivation

- Reward and reinforcement

- Techniques of teaching

- Techniques of teaching

KNOWLEDGE AND SKILL OF THE TEACHER

Throughout this chapter the case has been made that the objectives of the instructional program, the organization and content of subject matter, the interests and characteristics of clientele, and the principles of teaching and learning singly and collectively influence decisions teachers make about planning, delivering, and evaluating instruction. But there is one additional factor that holds the key to the process: the knowledge and skill of the teacher. Teachers must put the pieces together and integrate the system if learners are to acquire new knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

One dimension of teachers’ knowledge and skill is expertise in the science and technology of agriculture. Expert teachers are able to relate this knowledge and skill in a meaningful way to the world of work in general and to occupations requiring knowledge and skill in agriculture. Highly competent teachers of agriculture understand and value the science and theory that undergirds what is taught. They also possess the ability to perform practical skills. Actual work experience in agriculture is essential if teachers are to achieve the level of technical competence required for teaching agriculture successfully.

Another essential dimension of teachers’ knowledge and skill is their level of teaching competence, including an understanding of and the ability to use the principles of learning. Scientific, technical, and pedagogical competence are required if teachers are to direct the learning process such that students achieve to an optimum level the outcomes sought through instruction and study in and about agriculture.

It is important that persons preparing to teach agriculture and those who are teachers realize that it is essential that current knowledge and skill be continually updated and new knowledge and skill acquired if teaching is to be most effective. The continuing professional development of teachers pertains to their scientific, technical, and pedagogical competence. Teachers who are most successful are career-long learners both of what they teach and of how it is most effectively and efficiently taught.

SUMMARY

Factors influencing decisions about teaching include the purposes and objectives of the instructional program, the clientele being taught, the organization and content of the subject matter, principles of teaching and learning, and the knowledge and skill of the teacher. Objectives of instruction in agriculture relate to avocational and practical arts instruction (agricultural literacy), exploration of and orientation to agricultural occupations, development of occupational competence, and preparation for advanced study. Agricultural education is an integral part of public education. Clientele, subject matter, and instructional strategies describe the nature and functions of agricultural education. Characteristics of clientele, including interests and aspirations, background and home environment, experience related to the subject matter, previous instruction, academic attributes, and study skills influence decisions teachers make about teaching strategies. The knowledge and skill of the teacher are the overriding and integrating factors that result in an effective instructional program.

FOR FURTHER STUDY

Visit local schools offering instructional programs in and about agriculture. Discuss with the teacher purposes and objectives, clientele, subject matter of courses, instructional techniques and strategies, and the knowledge and skill needed by the teacher.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 1.1: Knowledge and skill of the teacher points to (1) clientele to be taught, (2) principles of teaching and learning, (3) purposes and objectives of agricultural education, and (4) organization and content of subject matter. These 4 point to instruction including planning, delivering, and evaluating.

- National Academy of Sciences, Committee on Agricultural Education in Secondary Schools. Understanding Agriculture: New Directions for Education. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1988. ↵

- The National Strategic Plan and Action Agenda for Agricultural Education: Reinventing Agricultural Education for the Year 2020. Washington, D.C.: National Council for Agricultural Education, 2000. ↵

- National Academy of Sciences, Committee on Agricultural Education in Secondary Schools, op. cit. ↵

- The National Strategic Plan and Action Agenda for Agricultural Education, op. cit. ↵

- Committee on Agricultural Education, Commission on Education in Agriculture and Natural Resources, National Science Foundation. Agricultural Education for the Seventies and Beyond. Washington, D.C.: American Vocational Association, pp. 6-7. ↵

- National Academy of Sciences, Committee on Agricultural Education in Secondary Schools, op. cit., 1988, p. vi. ↵

- Warmbrod, J. Robert. "Individual Goals and Vocational Education." In Alfred H. Krebs (Ed.), The Individual and His Education. Washington, D.C.: American Vocational Association, 1972, pp. 119–128. ↵

- Bugelski, B. R. Some Practical Laws of Learning. Bloomington, IN: The Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, n.d., p. 30. ↵

- Bender, Ralph E., and Boucher, Leon W. Classroom Climate for Effective Learning. Columbus, OH: Department of Agricultural Education, 1977, p. 4. ↵