14 Evaluation of Learning

Sara was a good student in the agriculture program. She received the highest score on nearly every test given in class. Her agriculture teacher awarded her an A on her report card. Becky had more difficulty in school. She received a D in her agriculture course because of her test scores.

The agriculture teacher placed both Becky and Sara on an SAE “Coop” placement with a local nursery. After a short period of time, the nursery manager telephoned the teacher. He praised Becky’s work, indicating that she was an excellent worker. However, he expressed displeasure with Sara’s know-it-all attitude, her “bossiness” with other employees, and her lack of work ethic. The manager awarded Sara a D on her report card while awarding Becky an A on her report card.

Evaluation is assessing what students have learned. Evaluation provides useful information to students. It also helps teachers determine whether students are learning what is being taught, and in so doing assists the teacher in self-assessing effectiveness of content delivery.

Were the grades the students received in the preceding example appropriate? It depends on how they were evaluated and the basis for the evaluation. For example, was the evaluation based on course objectives? Were the course objectives related to developing knowledge, attitudes, and performance of skills?

OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you will be able to

- Explain the reasons for evaluating students.

- Evaluate achievement based on objectives.

- Plan a test.

- Construct various types of paper-and-pencil tests.

- Develop various types of rating scales and performance assessment instruments.

- Develop a grading procedure.

- List alternative evaluation strategies.

REASONS FOR EVALUATING LEARNING

The evaluation of learning is a significant part of the job of a teacher. Accurate assessments provide a clear picture of a student’s performance in relation to the objectives of the curriculum and in relation to other students. Completing various types of assessment prepares individuals for evaluations throughout their careers. They are learning that performance is a major determinant of their status in life and that their status is often a result of assessments of their performance as perceived by others. Therefore, teachers have a responsibility to use evaluation instruments and procedures that are unbiased, justifiable, and realistic.

Needs Assessment

Knowledge of the level to which students have developed enables the instructor to effectively plan for teaching. Thus, baselines of the students’ educational levels are needed, along with a set of measurements and tools for benchmarking their progress. For example, a diagnosis of learning difficulties provides information helpful in designing individualized instruction. Pretesting is a tool that can be used to suggest when remedial instruction is in order, or whether students have already been taught the unit that is planned. Because it is a waste of time to present content the students have already mastered or material that the students lack the prerequisite skills to grasp, a pretest can help determine knowledge level and, therefore, a starting point for teaching the content. Agriculture teachers have been challenged to take students from where they are to where they want to be. In order to accomplish this task, it is necessary to determine where they are. One important reason then for evaluation of students is to determine what students know or can do prior to teaching a unit of instruction.

Instructional Improvement

Evaluation of student learning provides valuable feedback to the teacher concerning the effectiveness of instruction. Tests can aid teachers in assessing the effectiveness of instructional materials used. Tests can also be helpful in evaluating the usefulness of teaching methods or techniques.

Evaluation can indicate that an entire class failed to grasp an essential concept and can further help the teacher ascertain where additional emphasis is needed. Exam results are useful in determining whether the material is above or below the ability of the students. Teacher-developed evaluations assess the teacher’s instruction as much as they do the students’ achievements. From evaluations, a teacher can see where better examples or other adjustments are needed. Even the process of planning and constructing an evaluation will encourage the teacher to effectively present important knowledge and skills on which the students will later be assessed. If a few individual students are finding the material either too easy or too difficult, the teacher may need to further develop individualized instruction that is challenging but attainable.

Motivation

Evaluation can be used to encourage some students to study and learn. Students who want good grades tend to respond favorably to the challenge of a test. Fear of failure, desire for academic success, and avoidance of guilt and anxiety may positively persuade students to learn material that is not otherwise rewarding. It has been shown that frequent testing with teacher-made tests, compared with infrequent testing, has generally resulted in improved student performance. This may be because the teacher is better at using feedback to improve instruction, or it may be because students are motivated to learn to do well on an examination.

However, students who experience test anxiety or who have a history of performing poorly on written exams must be provided with alternate approaches to evaluation other than traditional paper-and-pencil tests if their motivation is to remain at its highest levels.

Self-Appraisal

Students may use evaluations to rate their own performance and correct errors on their own. The use of evaluation instruments for this purpose is especially helpful in developing performance skills. Students can self-rate their progress, their project, or laboratory work to determine if it meets a preestablished standard of mastery. They then can choose to improve their performance by further study and practice. For evaluation to be useful for self-appraisal, the standards for performance must be clearly communicated to students.

Instruction

A test is often the climax of a unit of instruction. It functions as a vehicle to encourage students to synthesize previous material as they review for the exam. It also reemphasizes important objectives. To be most effective, the teacher should give corrective and constructive feedback as soon as possible after the students have completed an exam. This process will enable students to learn material they earlier failed to grasp. Content on which students have been tested is more likely to be remembered.

Grades

Schools are accountable to students, parents, and the community for teaching. An important measure of what has been taught is what students have learned. Most schools express the extent to which each student has learned in the form of grades. Grades are the means of communicating with others about the degree to which a student has achieved the objectives of a course. Teachers of agriculture must be able to justify the grades they award. One important input as decisions about grades are being made is the scores on teacher-developed evaluations of learning.

Evaluation Based on Objectives

Well-written objectives describe the learning expected of students. Well designed evaluation results describe whether the objectives were reached at a satisfactory level. Thus, evaluations of student achievement should measure achievement of objectives. Evaluations should not be designed to measure obscure bits of knowledge but should measure the central focus of instruction. Objectives, therefore, are not only important in planning for teaching but are also essential for use in constructing evaluations.

An evaluation is more likely to be valid if it is written to measure whether students have achieved specified objectives. Evaluations that are not valid have no value other than as a measure of general knowledge, unrelated to the instruction that has been given. Teachers normally would want the content of the evaluation to be:

- The same as that presented in the course

- As comprehensive as the objectives on which the students are being evaluated

- Specific to the competencies that were identified in the objectives

Planning a Test

Tests can have motivational and instructional value if properly constructed. The objectives for the course serve as guides to the students about what is important to be learned and, therefore, serve as the guide to test construction. A haphazardly designed test that emphasizes trivial knowledge frustrates students. They may become discouraged rather than being motivated to learn more.

Specification charts (see Table 14-1) help to ensure a valid and comprehensive test. These charts can help teachers make decisions about test content. Exams that have been planned with the help of specification charts are more likely to cover the important knowledge and skills emphasized in the instruction.

| Level of cognition | Area | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instructional content | Relative emphasis | Knowing | Comprehending | Applying | Affective | Performance | Item total | Number points |

| 1. Name the advantages of being an owner-operator | 2% | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2. Explain how to establish ownership programs | 6% | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 3. Develop growth objectives | 10% | 1 | 4 | 5 | 13 | |||

| 4. List the different types of business applications | 5% | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| 5. Develop written plans and goals | 10% | 1 | 4 | 5 | 13 | |||

| 6. Develop a financial statement | 10% | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 13 | ||

| 7. Develop a budget | 8% | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | |||

| 8. Set up and enter inventory records | 8% | 4 | 4 | 6 | ||||

| 9. Describe various efficiency measures | 5% | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 10. Set up and keep expenses and receipt labor records | 8% | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | |||

| 11. Set up and keep nonfinancial records | 6% | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 12. Prepare a financial summary | 7% | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 13. Demonstrate acceptable personal appearance and hygiene | 15% | 7 | 7 | 26 | ||||

| Total items | 10 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 19 | 50 | 100 | |

Table 14-1: Specification chart for "finalizing my ownership supervised agricultural experience"

One of the first steps in constructing a specification chart is to itemize the content to be learned by students—the instructional content. For example, if you were planning a test for the unit of instruction “Finalizing My Ownership,” the objectives should be identified from the content based on the learning outcomes that were sought. Table 14-1 shows a specification chart with the instructional content listed.

In addition to using a specification chart to select the content to be included in an examination, the teacher can assign weights to each objective based on its relative importance. The assignment of relative emphasis to objectives might appear as is shown in Table 14-1. The teacher who taught the material is best qualified to determine the relative emphasis.

The next decision faced by the teacher is to decide whether to develop a paper-and-pencil cognitive test, an affective rating scale, or a performance test. If a cognitive test is to be used, then the questions should reflect the level of desired learning. Were the students to learn facts, comprehend material, or apply information? The level of the evaluation should be consistent with the level of the objectives. Table 14-1 assumes fifty possible points to be awarded for an entire unit of instruction. Of these, nineteen would involve performance appraisals, with students actually doing the work and being evaluated on the result. Seven points are to be awarded on an affective rating scale. A 100-point written examination would be used to evaluate the students’ knowledge, comprehension, and ability to apply their learning. The number of test items measuring each objective should be in proportion to the importance initially weighted to that objective and should be reflected in the design of the specification chart.

Many teachers fail to use enough items in developing a test. A longer test is more reliable. A longer test also can more comprehensively test the objectives. The length of the test also depends on how often a teacher gives exams. Similar results can be obtained from many short quizzes or a few long tests. In either case consider this. If a unit of instruction takes eighteen class meetings to complete, and each day the teacher provides a ten-minute (five to ten mixed items) quiz, the same amount of time would be used if students completed three one-hour exams, yet the learning was reinforced in smaller increments across the eighteen sessions. The teacher should feel confident that the scores have accurately measured what students have learned. This is more likely to occur if evaluations are of sufficient length and at appropriate intervals to provide consistent results.

MULTIPLE-CHOICE TESTS

Multiple-choice items consist of a lead-in statement known as the stem, followed by a number of possible responses. Only one of the possible responses should be correct. The others, or the incorrect responses, are known as distractors. Most students and teachers have had considerable experience with this form of test question.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The popularity of the multiple-choice test is based on perceived advantages of this type of test over other types. Some benefits include:

- Adaptable for use in a wide range of testing situations

- Less ambiguous than completion or true-false questions

- Less susceptible to chance errors resulting from guessing than true-false items

- More objective than tests in which students supply the response

- Well adapted to machine scoring

- Easily understood by students

- Can measure recognition as well as recall

Multiple-choice tests do receive some criticism. Critics of this type of test item are often generally critical of all objective-type tests. Some of the criticism is legitimate because of the misuse or improper preparation of a test. Major disadvantages include:

- Failure to commit time to proper development of items

- Failure to develop items measuring higher-cognitive levels than recall or memorization

- Improper distractors, either making the correct choice obvious or causing some debate among experts as to whether only one choice is correct

- Space-consuming, causing the appearance of a long test

- Time-consuming to properly construct

- Conducive to guessing

Steps in Constructing Items

The previously discussed specification chart should be used as one begins to construct test items. Determine the major knowledge and skills to be tested relating to each objective, then prepare a question or an incomplete sentence that clearly implies a question. This is the stem. A good answer with a few well chosen words should be written to the question. Several (usually three) incorrect answers should then be written. These distractors should be plausible to the student who lacks understanding of the question.

Good multiple-choice items deal with important ideas, not with insignificant details. Too often teachers ask questions on illustrations or similar materials found in a text or discussed in class. These illustrations were designed to teach a concept, not in themselves to serve as the focus of the learning. Table 14-2 shows an item that could be used in partial measurement of the objective, “Name the advantages of being an owner-operator.”

| What is a major advantage of a well-planned ownership program? |

|---|

| a. helps in improving the appearance and value of an agribusiness |

| b. helps in gaining experience in working for others |

| c. helps in accumulating earnings* |

| d. helps provide assurance of regular wage income |

| *Correct response |

Table 14-2: Item measuring a specific objective. Source: Amberson, Max L., and Anderson, B. Harold. (1978)Learning through Experience in Agricultural Industry, New York: McGraw-Hill. Reproduced under fair use.

Teachers should avoid the use of opinion stems in multiple-choice items. Asking a student for an opinion as to a best answer will result in disagreement. Even though a student selects an answer the teacher believes is wrong, it is still the student’s opinion and thus the answer as stated is correct.

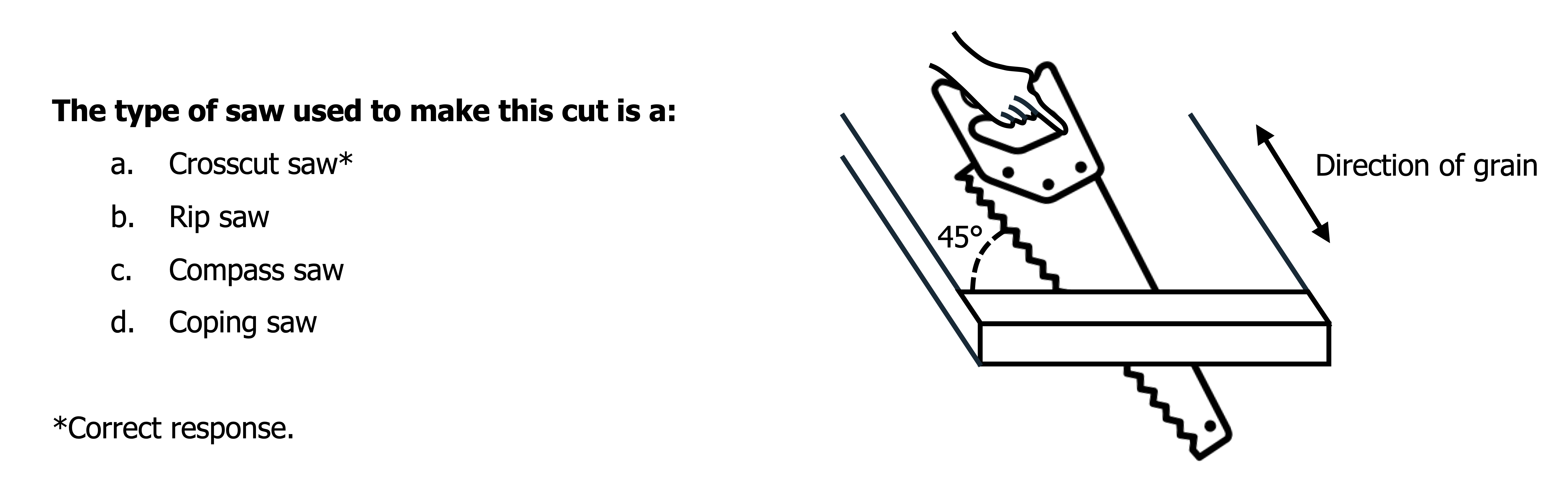

It is sometimes helpful to illustrate a question. Student understanding can then be readily tested. For example, in Figure 14-1, one could easily test the application of what saw might be used in cutting across the grain of a board.

Teachers of agriculture should always attempt to word the stem positively, avoiding negative terms. When it is necessary to use negative terms, underline them for emphasis.

Avoid providing false clues or irrelevant information in the stem. The student should be able to quickly decipher the intended purpose of the question.

Careful wording of alternative responses is needed. All the responses should seem plausible, but only one should be clearly correct. Following are some suggestions for writing multiple-choice test items:

- All alternative answers should be appropriate to the question.

- All responses should be grammatically consistent with the stem.

- All responses should be similar in type of content, length, and complexity.

- There should be at least four choices.

- Each choice should be listed on a separate line.

- A series of figures should be listed in order.

- Correct responses should be scattered.

- Responses such as “all of the above” and “none of the above” should be avoided.

- Distractors must be plausible alternatives. Some ways of obtaining them include:

- Using true statements that do not correctly answer the stem question.

- Using common expressions or phrases that may seem attractive to students whose knowledge is only superficial.

- Avoid distractors that are unfamiliar to the students.

- Avoid dis tractors obviously incorrect, even to those not familiar with the material.

“All of the above” and “none of these” can be used when the responses deal with an absolutely correct or incorrect question such as an answer to an arithmetic calculation or spelling of words. They should not be used for answers that are “best” responses.

SHORT-ANSWER TESTS

A short-answer test is one in which a student is asked to supply a number, phrase, or word that answers a question or completes a thought. It is best suited to testing recall knowledge. The teacher forms the stem (as either a question or an incomplete statement), leaving space for the student to respond. A sample item is exhibited as Table 14-3.

| What is the term used to describe the end of a meeting? |

|---|

| Answer: Adjournment |

Table 14-3: Sample short-answer item

Advantages and Disadvantages

The short-answer item is highly accurate in assessing knowledge. It has several additional advantages:

- Low chance of guessing correct answer

- Reasonably easy to write

- Requires less room on a page per item than multiple-choice items

- Easily understood by students

Some disadvantages of this type of item include

- Less objectivity in scoring than where students choose from among listed responses; therefore the test should be scored by a knowledgeable person

- Less adaptability to measuring higher cognitive items than those dealing with recall of knowledge

- Susceptible to improper use when hastily developed

Steps in Constructing Items

A problem many teachers have in writing short-answer items is that there may be several equally defendable answers to a question. For example, the question “Personal data sheets should be what?”[1] to which the intended answer was “neat, accurate, and typed,” might also elicit such answers as “used to get a job,” “reviewed by a friend to see if they are complete,” or “printed on 81/2″ x 11″ paper.” Questions of this type should be worded to encourage a specific desired response. Following is a question designed to test recall of information for which there is only one correct response. “FFA makes a positive difference in the lives of students by developing their potential for premier personal , and success through agricultural education.” Answer: leadership, growth, career. Be careful, however, depending on the nature of the question, to have fewer as opposed to more blanks in the item, and to carefully choose the placement of the blanks toward the end of the phrase so the students get the nature of the question prior to the blank(s). Additional considerations in developing short-answer items are as follows:

- Decide on the desired answer, then write a question to obtain the appropriate response.

- Avoid lifting items out of their context; the answer out of context may be difficult to defend as the only correct response.

- Make all blanks the same length.

- Arrange blanks at either the right or left margin of the page for ease of scoring.

- Avoid unintended clues (example: “The leadership committee is responsible for developing student abilities in ____ .” Answer: leadership)

- Word items differently from in the reference material to elicit greater processing, thus, understanding

TRUE-FALSE TESTS

A popular form of test item among classroom teachers is the true-false item. This is probably because it is viewed as being easy to write and score. Well constructed items do discriminate between students who have mastered the material and those who have not. However, there is general agreement that true-false tests, as written by many teachers, tend to confuse students. The most common uses of true-false tests are in identifying the correctness of definitions, statements of principles, and statements of facts. Complex and difficult problems can also be presented in this form.

Advantages and Disadvantages

True-false tests are efficient. Students can respond to many items in a short period of time. Therefore, a large body of knowledge may be tested in one examination. Other advantages are as follows:

- Relatively easy to write

- Scoring is objective and easy

- Well suited to force a choice between two options

Many teachers and students are critical of using true-false items because of their limitations. Some major disadvantages are as follows:

- Guessing is a factor; students have a reasonable chance of guessing the correct answer even though they have not learned the appropriate objectives.

- The item reliability is low, forcing a high number of items per test to accurately measure the content of a unit of instruction.

- Each item has less value in assessing how well students have achieved specific objectives; therefore, a high number of items per objective is needed.

- Students learn to make use of word clues, and some can score well with little knowledge of the material.

- It is difficult to construct a completely true or completely false statement without making the answer obvious.

- Be careful not to emphasize minor details for which items are easier to write.

Steps in Constructing Items

A true-false question should test an important concept. For example, if you were teaching the breeds of beef cattle, the country of origination of the Angus breed would be much less important than the fact that they are known for their excellent conformation (body type). However, a true-false item about origination is easier to write than an item about conformation.

The question should be designed to encourage students to think rather than only memorize. Following are two examples of items written to test at different cognitive levels. Item 3 was written to (1) reduce guessing on a true-false item and (2) raise the cognitive level at which a student responds to the item by forcing them to think through and write an explanation.

COMPARISON OF COGNITIVE LEVEL TEST ITEMS

- Memorization

- Softwood comes from coniferous trees. (T)

- Thinking and Understanding

- If one were to construct a nursery lath house, one would normally use poles made from deciduous trees. (F)

TRUE-FALSE ITEMS THAT ENCOURAGE THINKING

1. In the spring of the year pasture grasses are the main source of water for hindgut fermenters.

Explain

Following are some suggestions for developing true-false questions:

- Make approximately one-half the items true and one-half false; if a test is unbalanced, have more false items.

- Make the method of indicating responses simple; one might put a typed T and F to the left of each item for a student to circle.

- Do not make true statements consistently longer than false statements.

- Avoid negative statements.

- Use only a single idea in each statement.

- Word an item so superficial logic suggests a wrong answer.

- Do not lift sentences directly from a textbook.

- Do not organize true and false items in a predictable pattern.

MATCHING TESTS

A matching test contains two sets of items to be associated by the student on the basis of the set of directions supplied by the teacher. One set of items is a list of premises, the other a list of responses. In most cases, the lists could easily be interchanged, as, for example, one could either match dates to events or events to dates.

The matching item is really a form of multiple-choice testing. The student is expected to select a correct response from a list containing several distractors. A wide variety of types of lists may be matched. Examples include a chart of parts of an animal with names of the parts, plant common names with botanical names, dates with events, tools with names or use, and wildlife with area of habitation.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Matching items are efficient. Many items can be placed on a page. Students can answer items quickly. Thus, much material can be tested in a short period of time. Students are encouraged to integrate their knowledge as they attempt to match items from related sets of material.

Matching tests are generally limited to specific factual information. It is quite difficult to construct items to test for comprehension or application of material. Because matching requires choosing from a cluster of related items, some material in any given unit of instruction may be left out simply because it does not fit a cluster. Thus, matching items are seldom appropriate as the only method of testing in a unit. This method can, however, be a useful part of a test that also contains other types of items. Teachers must be careful to properly construct this type of test.

Steps in Constructing Items

Several basic practices are essential to developing good matching tests. Improperly constructed items allow the student to readily eliminate incorrect responses and correctly guess the correct response.

Related Sets. The premises and responses within a set must be related (homogeneous). Figure 14-2 illustrates how the items are related throughout the matching list.

Responses per Set. In most cases, there should be at least six but not more than ten responses per set. There may be exceptions for identification items. Shorter lists make it easier to keep items homogeneous. Normal practice might be to have three premises and five responses. Indicate to the students whether responses can be used more than one time. There should be at least three plausible choices for each premise.

Extra Choices. Use extra choices in the response list to reduce the chance of guessing the correct answer. This idea can be achieved by permitting the response alternatives to be used more than once or by adding extra responses. Again, when this is the case, indicate so to the students in the instructions. Note in Figure 14-2 that there are three incorrect responses in addition to the correct responses.

Logical Arrangement. Items should be arranged so students do not have to spend excessive time hunting for them. Put them in alphabetical or chronological order unless some other system is preferred. Note the order of the responses in Figure 14-2.

One Page. Never carry a matching set over from one page to the next. A student becomes confused when he or she must flip pages while seeking a correct response.

ESSAY TESTS

The essay test is familiar to most teachers and students. It is a form of free response item that allows students to provide information in their own words.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The essay item is quite useful in assessing learning requiring the recall, organization, and presentation of ideas. The student must supply rather than choose a correct response. Proponents of essay exams suggest they:

- Develop abilities in written expression

- Require the student to use high mental processes

- Encourage deep study to prepare for the test

- Encourage creativity

They are much easier for the teacher to construct than most other test forms.

Although an essay exam does not provide opportunity for a student to guess the correct response, there is opportunity for bluffing by the student. The distribution of scores on an objective test is determined by the exam. On an essay test, the grader determines the distribution.

Essay tests are low in reliability. Different graders will score exams differently. Also, essay exams require a great deal of time for students to respond to each question; therefore, a smaller portion of the content can be sampled. When the questions are not clear to all the students, a wide range of responses will contribute to the low reliability.

Essay tests should not be a measure of the students’ ability to write if the purpose of the test is to measure knowledge of some subject matter. Too often the score is a reflection of ability in written expression. This is not to say that grammar and spelling should be ignored. However, it must be remembered that the primary purpose for the exam is to assess the knowledge learned from the content that was taught.

The time saved in constructing essay exams is more than lost in grading them. They are difficult to grade uniformly. Students have a tendency to “pad” their answers. Misinterpretation of the question can cause a poor score even though the student may understand the material. Many of the deficiencies can, however, be kept in check with proper item preparation.

Writing Acceptable Questions

The teacher should primarily use essay items to test learning that short answer items do not test as well. Always ask questions for which experts would agree there is a clearly correct answer. Do not simply ask students to discuss their opinions relating to a topic. Such questions are impossible to fairly grade.

Be as specific as possible in defining what is expected of the student. Give preference to more questions of a specific nature rather than fewer general questions. Do not give a student a choice among questions. Giving the student the option of answering any two of three essay questions will not differentiate between students who can answer all three and those that can answer only two of three. It is also impossible to equate the difficulty of optional questions.

After writing the question, the teacher should either write an ideal answer or, at a minimum, list the essential information expected of the student. Students should be informed before the test as to how their answers will be scored—whether the teacher will take off for grammatical errors or for incorrect information, or just determine if the relevant information is present.

Grading Student Answers

The value of essay exams largely depends on the quality of the grading process. The teacher must take extra care to be consistent and fair in rating the essay answers students have written.

Use a Consistent Scoring Method. The teacher may choose to specify crucial elements of an ideal answer. The proportion of these crucial elements appearing in his or her answer determines a student’s score. This type of grading provides clear justification to the student of the attained score. This system is best suited to questions likely to have uniformly structured answers.

Another method, perhaps better with questions having complex answers, is to simply read an answer and assign a numerical grade based on the rater’s general impression of the response. A better, related system is for the teacher to sort the answers to a question into piles having corresponding levels of quality. Scores can then be assigned. Although this method may be as reliable, it is more difficult to justify scores to students.

Grade One Question at a Time. The teacher should read the answers to one question on all the students’ papers before going on to the next question. The teacher can concentrate on the answer to the one question and more fairly grade each of the students’ responses to that question. It is suggested that teachers read through every response to one question without assigning a grade, and then reread the same items before awarding a grade.

Grade Items Anonymously. Answers can more nearly be graded on merit when the teacher examines an item without knowing who wrote it. Students can put their names in a place on the paper where the teacher need not see it until after the scores are assigned. This may be difficult in small classes where the teacher may recognize the handwriting. However, the teacher should make every effort to fairly and independently judge each response.

ORGANIZING AND ADMINISTERING A TEST

After the test items have been written, they should be arranged to assist the student in taking the test and for ease of scoring. If the teacher has followed the test plan, the items will represent a good example of the skills and knowledge to be tested. There should be a sufficient number of items to provide a reliable estimate of a student’s knowledge and skills.

Organizing the Test

The first step in organizing a test is to group like items together. All the multiple-choice items should be in one section of the test, the true-false items in another section, and so on. In this way, the directions need be given for responding to the type of item only once.

Once the items are sorted by type, they should be arranged according to their level of difficulty. In other words, all the multiple-choice items should be arranged so the easier items appear first followed by increasingly difficult items. Classroom teachers need not be overly concerned as to whether items are in an exact order of difficulty. In general, however, the items should be arranged in this way.

Another important point in organizing the test is to arrange items for ease of scoring. Normally, the spaces for student responses should appear in a column running from the top to the bottom of the page. Even in fill-in-the blank questions, items can have the answers appear in a vertical column (see Table 14-4). Some teachers prefer to use separate answer sheets for objective items that may be machine- or hand-scored more quickly.

| Questions | Answers |

|---|---|

| 1. The rental charge for use of capital is ___(1)___ | 1. Interest |

| 2. Ownership capital is ___(2)___ capital and rented capital is ___(3)___ capital. |

2. Investment |

| 3. The portion of profits distributed to investor owners is known as ___(1)___. | 3. Loan or borrowed |

| 4. Dividends |

Table 14-4: Fill-in-the-blank item with choices arranged vertically. Source: Long, Don L., Oliver, J. Dale, and Coale, Charles W. Introduction to Agribusiness Management. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1979, pp. 47-50. Reproduced under fair use.

Directions should be prepared to advise the students concerning the test. The amount of detail in the directions should relate to whether the student is familiar with the type of exam being administered. General directions should cover

- Putting his or her name in the proper space

- Time allotted

- Whether guessing is encouraged or whether there are points off for guessing

- Whether students may ask questions for clarifying an item

- Necessity for following directions for each type of item

- Specific directions for each part of the test might include

- Procedure for responding to each item

- A sample item that has been completed

Examine the physical arrangement of items. Some hints are as follows:

- Leave sufficient space for all responses.

- Arrange items so responses will not form a particular pattern.

- Arrange items so students do not need to refer to more than one page to answer them.

- Number items consecutively from the beginning to the end of the test.

- On multiple-choice and similar items, arrange possible responses in a vertical rather than horizontal row.

A scoring key should be prepared prior to administering the test.

Administering a Test

This is probably the simplest phase of the testing process. Concerns in administering a test usually relate to time limits and cheating. However, it is also a responsibility of the teacher to prepare the students in test taking.

Students should be made aware of the importance of following the directions and the consequences of not doing so. They should understand how the test will be scored. Will points be subtracted for guessing? Will points be subtracted for errors in spelling? Will there be a premium for legibility and neatness? Students should be encouraged to pace themselves rather than spending excessive time on a difficult question. The teacher should provide guidelines for planning and organizing responses to essay questions.

If time limits are imposed, the teacher may make students aware of time constraints by writing the time remaining on the chalkboard periodically. However, know your students because indicating time could cause some students to panic.

The teacher has a definite responsibility to prevent cheating. The examination should be administered in such a way that cheating is not encouraged. Examination copies should be safeguarded prior to administration. Students and teachers must recognize that cheating requires consistent application of appropriate penalties such as failure, loss of credit, or suspension. The instructor must not allow cheating to be easy. Alternate forms of the exam may be prepared by arranging questions in a different order. An exam should be proctored at all times. Summary tips on administering a test follow:

- Announce the test well in advance of the test date so students have ample time to study, especially if a significant portion of the course grade will depend on the test score.

- Type the test and make copies of it; don’t write questions on the writing surface or read them aloud.

- Produce clean, legible copy; have extra copies available.

- Fit the test to the available time; announce the time allotted; give at least ten- and five-minute warnings.

- Administer the test in a comfortable, familiar setting.

- Seat students so as to reduce any temptation to copy.

- Make sure all are ready to take the test: sharpened pencils, desks clear of books and notes, and so on.

- Distribute test papers face down and have all students start at the same time.

- Explain the instructions.

- Supervise the test; move quietly about the room; do not become involved in other duties.

AFFECTIVE ASSESSMENT

Affective assessment is concerned with measuring the interests, attitudes, values, and appreciations of students. In preparing students for work in agribusiness, these areas are quite important. In many cases, the affective area is as important in obtaining and keeping a job as the cognitive and psychomotor skills of a student.

The agriculture program has many aspects designed to develop the affective domain of students. The supervised agricultural experience program develops student initiative and responsibility. Work habits are developed in the agricultural mechanics laboratory, the greenhouse, and through other skill development avenues. The FFA organization provides opportunity for developing career success skills, citizenship, and leadership. Assessment must be designed and implemented to measure student progress in each of these aspects of the agricultural instruction program.

It is difficult to measure interests, attitudes, values, and appreciations. Also, some believe that education should be value-free. However, if the role of agricultural instruction is to prepare students for life beyond high school, then the affective development of students must be written as objectives and measured for accountability.

Some appropriate measures currently used by teachers to assess affect (interests, attitudes, etc.) include direct observation, observer checklists, progress charts, rating scales, and assessment rubrics.

Direct Observation

Many teachers of agriculture consider student “attitude” in assigning grades. Students who work hard and are cooperative are often given the benefit of the doubt when their scores are near a break between two grades. Some teachers average an “attitude” score with scores obtained on other measures of achievement in arriving at a final determination of grades. Such practices are often based on perceptions of the teacher who has directly observed student behavior.

The reliable observation of affect is difficult. Students who know they are being observed often respond differently from when observation is not apparent. Many students reflect socially acceptable behavior among peers but may exhibit different behavior in a work setting. Affective behavior is very difficult to quantify. Although most observations of affective behavior have been informal, teachers facing a need to justify evaluations of students have desired a more formal approach. Checklists and rating scales may be developed and used to measure affect and to communicate with students and parents about observed behavior.

Checklists

Checklists are a convenient way for teachers to rate student behavior. They can easily be developed simply by listing the desired traits to be observed. For example, a teacher might work with students to cooperatively develop a list prior to a field trip to encourage the affective expected behaviors. Some teachers have students rate themselves and then discuss differences between student and teacher ratings in individual conferences. Thus, the list is used for counseling as well as evaluation. An example checklist is shown in Figure 14-3. Teachers who use checklists of this nature must be sure that students have the opportunity to participate and practice the desired behavior.

Rating Scales

Rating scales are similar to checklists, except that students receive a quantitative score on each item rather than an all-or-none decision. Figure 14-4 is a rating scale containing items to assist students in developing cooperation, responsibility, leadership, work habits, and social habits. The specific items could be revised to meet the needs of any local program. Teachers could have students complete a weekly self-rating, using this or a modified form. Teachers then respond to the student with revisions as needed. Student improvement then becomes a cooperative venture rather than the teacher encouraging a reluctant student. The scores on scales of this nature can be used as a measure of student achievement in the affective domain.

| Category | Indicators | Rating* |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cooperation | a. Works well with peer students b. Seeks help when needed c. Assists others d. Is receptive to suggestions |

1 2 3 4 5 N |

| 2. Responsibility | a. Completes assigned work b. Follows policy and rules c. Assumes responsibility for actions d. Attends regularly e. Is on time |

1 2 3 4 5 N |

| 3. Leadership | a. Influences others b. Makes decisions c. Provides constructive criticism d. Develops and works toward personal goals e. Demonstrates initiative f. Demonstrates poise and confidence |

1 2 3 4 5 N |

| 4. Work habits | a. Works well under pressure b. Works rapidly and accurately c. Demonstrates patience d. Uses available time |

1 2 3 4 5 N |

| 5. Social habits | a. Meets people properly b. Uses appropriate dress c. Respects the rights of others d. Is well groomed e. Is concerned about others |

1 2 3 4 5 N |

| *A rating of 5 means excellent; 4, very satisfactory; 3, satisfactory; 2, needs improvement; 1, poor; and N, not applicable. | ||

Figure 14-4: Example of a personal development rating scale. Source: McCracken, J. David, and Bartsch, Bruce P. (1976) Developing Local Courses of Study in Vocational Agriculture. The Ohio Curriculum Materials Services, p.44. Used with permission of The Ohio State University and released under CC BY NC SA 4.0.

Assessment Rubrics[2]

Often in an attempt to grade students’ work it is found that the assessment criteria are vague and the performance behavior was subjective. Rubrics are authentic assessment tools that are useful in assessing criteria that are complex and subjective (see Table 14-5 for an example assessment rubric).

Authentic assessment is geared toward assessment methods that correspond as closely as possible to real-world experience. The teacher observes the student in the process of working on something real, provides feedback, monitors the student’s use of the feedback, and adjusts instruction and evaluation accordingly.

The rubric is one authentic assessment tool that is designed to simulate real-life activity where students are engaged in solving problems. It is a formative type of assessment because it becomes an ongoing part of the whole teaching and learning process. Students themselves are involved in the assessment process through both peer and self-assessment. The advantages of using rubrics in assessment are as follows:

- They allow assessment to be objective and consistent.

- They focus the teacher to clarify his or her criteria in specific terms.

- They clearly show the student how his or her work will be evaluated and what is expected.

- They promote student awareness of criteria to use in assessing peer performance.

- They provide useful feedback regarding the effectiveness of the instruction.

- They provide benchmarks against which to measure and document progress.

Rubrics can be created in a variety of forms and levels of complexity; however, they all contain common features that

- focus on measuring a stated objective (performance, behavior, or quality)

- use a range to rate performance

- contain specific performance characteristics arranged in levels indicating the degree to which a standard has been met

Teachers of agriculture may use direct observation, checklists, rating scales, and assessment rubrics as measures of affective behavior. Students should be encouraged and rewarded as they develop the interests, attitudes, values, and appreciations needed for successful entry and advancement opportunities after high school.

| Competency builder (criteria) | Mastery or above proficient | Proficient | Below proficient | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed problem | The student has acquired knowledge to correctly diagnose the problem. In addition, they are able to accurately distinguish between 3 or more problem-solving or decision-making models, which better assists the student in solving the problem. | The student is capable of identifying the problem. In addition, they are able to accurately distinguish between 1 and 2 problem-solving or decision-making models, allowing the student to correctly solve the problem. | The student has no logical understanding or knowledge of how to solve the given problem. | |

| Gathering data | The student demonstrated their ability to gather relevant information. For those sources that were not used, the student cited and explained why they were not applicable. | By providing other case studies or similar data, the student demonstrated their ability to gather relevant information. | Although the student has acquired data, there is little evidence provided that justifies the data. | |

| Analyzing and comprehension of data | The student used comprehension strategies to identify more than 2 advantages and disadvantages of each solution. This information allowed the student to form logical and accurate conclusions from their data collection. | The student used comprehension strategies to identify 2 advantages and disadvantages of each solution. This information allowed the student to form knowledgeable conclusions from their data collection. | The student lacked the comprehension skills necessary to form more than 1 logical or accurate conclusion from their data collection. | |

| Effectiveness of the solution | The student has thoroughly examined the problem's progress, and has provided information confirming that the solution has had substantially positive results. | The student has thoroughly examined the problem's progress, and has provided information confirming that the problem is being maintained. | The student has provided little to no evidence on the progress of the problem, or the evidence that was provided suggests that the rates are continually decreasing. | |

| Follow-up | The student has continuously monitored the problem to prevent a reoccurrence in the future. In addition, the student inspects for any additional problems that may have arisen. | The student assesses the problem once a month to prevent a reoccurrence in the future. | After solving the problem, the student has not maintained any further assessment practices. | |

| Written communication skills | The plan is clearly written and is free of grammar, style, or formatting errors. | The plan is written so that formatting and/or grammatical errors do not distract the reader; style and formatting are within standard guidelines. | The plan is poorly written. It may contain many grammar, formatting, and style errors. |

Table 14-5: Example assessment rubric—Apply problem-solving techniques. Source: The Ohio Curriculum Materials Service. Used with permission of The Ohio State University and released under CC BY NC SA 4.0.

PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT

The primary use of performance evaluations is to assess student achievement. Three basic methods of measuring performance have been used:

- Observing and rating the procedures or process used to accomplish a task.

- Observing and rating the end product or project resulting from the performance of specified skills.

- Rating a student in a general assessment of overall performance.

Learning by doing has been an important theme of agricultural instruction throughout its history. Students have been involved in applying learning in the school laboratory, in their supervised experience programs, and by participating in FFA activities. Skill development is an important part of all career and technical education curricula. To only measure achievement through cognitive testing would not provide an adequate measure of learning.

Assessments of Process

Performance tests can be designed to evaluate whether students follow a correct procedure in performing a task. A performance test could be designed for a student to demonstrate the proper procedures for setting up an oxyacetylene torch, lighting the torch, and turning it off. The list of procedures could be developed according to the process described by Shinn and Weston.[3] Either the teacher or a committee of students could rate each individual student using a checklist. Students could be required to correctly perform the procedures, thus achieving a perfect score on the test, prior to using the oxyacetylene torch in the school laboratory.

A skill sheet (see Chapter 7) or learning activity package might help the student follow correct procedures. A skill sheet for preventative maintenance might include step-by-step procedures as shown in Figure 14-5. Figure 14-5 illustrates a performance test designed to ensure correct procedures are used. In this example, the students must master critical tasks. They must achieve a prespecified level on the overall test.

LESSON: PREVENTATIVE MAINTENANCE FOR

THE ELECTROLYTIC BATTERY

COURSE: Agriculture resource conservation

TERMINAL PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVE: The student will be able to accurately determine the state of charge of a battery by measuring the specific gravity of the electrolyte with a hydrometer.

GIVEN: An electrolytic battery of predetermined charge, hydrometer, comparative chart of specific gravity readings and charge.

PERFORMANCE: The student will be able to determine the state of charge of an electrolytic battery.

STANDARD: The student will be able to determine the specific gravity within 0.010 adjusted for temperature.

| Points awarded | Items to be observed | Sat. | Unsat. | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Removes battery caps | +2 | 0 | 1. Wears safety glasses. Places caps where they will not be lost. Allows sediment to settle before taking reading. | |

| 2. Inserts hydrometer into cell and draws electrolyte into barrel | +5 | 0 | 2. Holds the hydrometer vertically so that the float does not touch the sides. Does not read the hydrometer until the float rides freely. Leaves hydrometer nozzle in battery to prevent loss of electrolyte. | |

| 3. Indicates in notes the specific gravity (uncorrected for temperature) | +2 | 0 | 3. Writes specific gravity down in notes. | |

| 4. Returns electrolyte to cell | +2 | 0 | 4. Does not spill electrolyte. | |

| 5. Repeats steps 2, 3, and 4 for each battery cell | +4 | 0 | 5. Same criteria as above. | |

| 6. Replaces battery caps and flushes hydrometer with water | +2 | 0 | 6. Cleans hydrometer. Returns hydrometer to proper storage. | |

| 7. Adjusts specific gravity reading for temperature in notes | +5 | 0 | 7. Uses formula. [If temperature is greater than 80°F, add (+) four gravity points (0.004) for each 10°F above 80°F. If temperature is less than 80°F, subtract (-) four gravity points for each 10°F below 80°F.] Writes corrected specific gravity in notes. |

|

| 8. Compares specific gravity with state of charge chart | +3 | 0 | 8. Indicates in equipment log the state of charge of the battery. Charges battery if charge is less than 80%. Indicates in log if there is more than 0.050 variation in specific gravity of electrolyte between cells. |

TOTAL POSSIBLE SCORE: 25 points

MINIMUM MASTERY LEVEL SCORE: 20 points

TOTAL SCORE:

Figure 14-5: Performance test to determine specific gravity of a battery

Another example of a performance test is the individual safety test given by teachers of agriculture. Students must perform, to a prespecified standard, a series of tasks on each piece of lab equipment to successfully pass the test.

Performance measures of process are time-consuming to administer. They are needed, however, as measures of student mastery of the more important procedures.

Assessment of Product

Evaluation of a finished project completed by a student is a form of performance assessment. The teacher evaluates a finished product against a standard. A teacher might develop sample welding beads, with different beads used to illustrate varying quality of work. The quality of the work done by the student is compared with the standard to assign a score to the student project.

Some teachers use a skill chart to record the projects that have been satisfactorily completed by students. With a skill chart, students can check the competencies that have been satisfactorily completed. They can then compare their progress with others in the class. Quality scores, however, should be recorded in a grade book for privacy rather than on a skill chart that is displayed publicly.

Combination of Methods

Grades on laboratory work should be based on:

- The procedures used by the students

- The quality of the finished project

- The productivity or number of finished projects

Figure 14-6 illustrates a method of scoring that includes the three areas of assessment. A student’s score is determined by adding the values assigned for procedure and product. A total score for the unit of instruction can be obtained by adding the points for all completed work. This type of record is useful for communicating the reason for the grades that have been assigned.

Profit assessment 1

Student name:

| Required projects (sharpening and fitting) | Procedures | Product | Points for project | Score | Teacher's initials/date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Plane bit or wood chisel | 1.0 | 0.75 | 1.75 | B | |

| 2. Wood auger bit | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1.0 | C | |

| 3. Screwdriver | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | A | |

| 4. Twist drill bit | 1.0 | 0.75 | 1.75 | B | |

| 5. Cold chisel | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | A | |

| 6. Punch | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | C | |

| Optional projects (sharpening and fitting) | Double | ||||

| 1. Crosscut saw | 1.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | A+ | |

| 2. Rip saw | N/A | N/A | |||

| 3. Circular saw blade | N/A | N/A | |||

Procedures

- A = 1.00

- B = 0.75

- C = 0.50

- D = 0.25

Product

- A = 1.00

- B = 0.75

- C = 0.50

- D = 0.25

Score

- A = 2.0

- B = 1.5

- C = 1.0

- D = 0.5

Figure 14-6: Tool sharpening and fitting score sheet

Source: Wilson, Richard H. (n.d.) Methods of Student Evaluation. Columbus: The Ohio State University, Department of Agricultural Education, unpublished mimeo, p.20. Used with permission of The Ohio State University and released under CC BY NC SA 4.0.

Supervised Agricultural Experience Evaluation

In agricultural instruction, an integral component of the curriculum, and thus an expectation of students, is that they conduct supervised agricultural experience projects that combine across time into a total supervised agricultural experience program (see Chapter 10). An important area of performance assessment relates to measurement of student achievement in this area. Many teachers visit students once each grading period to review the status of the supervised experience program and to assist the student in further program planning and development. A form that teachers may use to evaluate the project during or following a home visit is illustrated in Figure 14-7A. The form takes into account the size or scope of the project, the student effort required, and the condition or quality. The scope score should reflect how well the student has made use of his or her opportunity for project work. A form that teachers may use to evaluate the total SAE program during or following a home visit is illustrated by Figure 14-7B.

| Project | Scope | Effort | Condition | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | ||||

| Wheat production | 2 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

| Pheasant release | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Grand total: 17/24 Grade: C+ |

||||

Figure 14-7A: Supervised agricultural experience project evaluation form

Assessment form

Student name:

| Initial | Basic | Commendable | Advanced | Superior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. _____ (0-10) Planning documents (e.g., training plans, agreements, plans of practice, procedures, and budgets). |

||||

| Initial (1-2) Explores and understands an SAE with supervision. |

Basic (3-4) Selects and develops planning documents for their SAE with supervision. |

Commendable (5-6) Shares responsibility for selecting an SAE and develops planning documents with supervision. |

Advanced (7-8) Selects SAE independently and develops planning documents with minimal supervision. |

Superior (9-10) Understands components and importance of planning documents; can complete documents independently and seeks input. |

| 2. _____ (0-10) Record keeping system. |

||||

| Initial (1-2) Selects a record system with instructor assistance. |

Basic (3-4) Keeps appropriate records in a timely fashion with supervision; begins resume. |

Commendable (5-6) Completes appropriate records with some supervision; understands the importance of records; has a current resume. |

Advanced (7-8) Maintains accurate records with minimal supervision; summarizes records; updates resume. |

Superior (9-10) Analyzes records, evaluates practices, and identifies alternatives based on their records with little supervision. |

| 3. _____ (0-40) Performance of OCAP (or an equivalent in occupations without OCAPs) competencies pertinent to the occupational goal of the student. This is a percentage calculation based upon the competencies in the applicable OCAP. Formula: Number of competencies experienced in real world setting as a part of an SAE/Number of core competencies 40. |

||||

| Initial (1-8) 0-20% performance |

Basic (9-16) 21-40% performance |

Commendable (17-24) 41-60% performance |

Advance (25-32) 61-80% performance |

Superior (33-40) 81-100% performance |

| 4. _____ (0-40) Extent to which the student directs the supervised agricultural experience program. |

||||

| Initial (1-8) Task identified by others, student works with supervision, student does not make decisions. |

Basic (9-16) Task identified by others, student works with minimal supervision |

Commendable (17-24) Task identified by others, student works independently, identifies some problems, and seeks help with solutions. |

Advanced (25-32) Shared decision making by student and other persons, student works independently. |

Superior (33-40) Student makes decisions based upon current conditions and works independently, identifies problems and solves them. |

Figure 14-7B: Supervised agricultural experience program evaluation form

Source: The Ohio Curriculum Materials Service (no citation available). Used with permission of The Ohio State University and released under CC BY NC SA 4.0.

Supervised Agricultural Experience Program—Performance Objective Planning Form

Student name:

Date:

| Mid-course targets | Standard | Planned | Actual | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st semester level | 8 | |||

| 2nd semester level | 18 | |||

| End of 1st summer | 34 | |||

| 1st semester level | 62 | |||

| 2nd semester level | 100 |

Signature (parent)

Signature (student)

Signature (cooperator/mentor)

Figure 14-7C: Supervised agricultural experience program evaluation form

The effort score should reflect the time and managerial commitment required of the student. The condition score should be an indication of whether approved practices are in use.

Another way of evaluating the supervised experience program is to rate the quality and condition of the student record book. The record book grade should be based on records being complete, accurate, up-to-date, and neat.

Teachers of agriculture ask employers to assist in rating students placed in cooperative education. Forms such as that shown in Figure 14-8 are designed primarily to measure total performance, including affective behavior. Teachers should advise employers on the use of the form to encourage consistency among employers in the rating of placed students. The final decision about the grades given as a result of the rating must rest with the teacher.

Student employee:

Date:

Placement site:

Instructions: Please rate the student employee on each of the following skills. Rate the student employee by placing a check mark in the appropriate column to the right of each skill. Use the following key for ratings:

X = No chance to observe

1 = Below expectation

2 = Meets expectation

3 = Above expectation

Teachers will find that evaluation of student progress must be a joint effort between themselves and the employer for students involved in placement programs. This will necessitate the use of a form by the teacher and employer to evaluate the progress of the student. The rating form used by the employer might be completed while the teacher is conducting a supervisory visit in order that they may discuss the evaluation point by point.

Figure 14-8A: Employer-teacher-student observation form

| General skills | X | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accepts and carries out responsibilities | ||||

| Attitude toward work, use of work time | ||||

| Adaptability; ability to work under pressure | ||||

| Speed and accuracy of work | ||||

| Attentiveness to work being done | ||||

| Promptness in reporting for work | ||||

| Care of work space | ||||

| Care of materials and equipment | ||||

| Observing, imagination | ||||

| Attitude toward customers | ||||

| Attitude toward workers, supervisors | ||||

| Personal appearance, grooming fitness | ||||

| Initiative | ||||

| Enthusiasm | ||||

| Cheerfulness, friendliness | ||||

| Courtesy, tact, diplomacy, manners | ||||

| Helpfulness | ||||

| Honesty, fairness, loyalty | ||||

| Maturity, poise, self-confidence | ||||

| Patience, self-control | ||||

| Sense of humor | ||||

| Selling ability, personality for selling | ||||

| TOTAL |

Figure 14-8B: Employer-teacher-student observation form (continued)

| Job skills (may be developed as a part of the development plan of each student) | X | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of merchandise | ||||

| Mathematical ability | ||||

| Handwriting | ||||

| Speech, ability to convey ideas | ||||

| Stock keeping ability, orderliness | ||||

| Use of proper English | ||||

| Desire to serve people | ||||

| Like people, not afraid of people | ||||

| Filling orders | ||||

| Check incoming freight | ||||

| Mark merchandise for sale | ||||

| Use computerized cash register | ||||

| Writing sales slips | ||||

| Making sales | ||||

| TOTAL |

Figure 14-8C: Employer-teacher-student observation form (continued)

Rating for liabilities:

X = No chance to observe

1 = Below expectation

2 = Meets expectation

3 = Above expectation

| Liabilites | X | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annoying mannerisms | ||||

| Making excuses | ||||

| Tendency to argue | ||||

| Tendency to bluff or "know it all" | ||||

| Tendency to complain | ||||

| TOTAL |

Please feel free to write comments below:

Evaluated by:

Position:

Figure 14-8D: Employer-teacher-student observation form (continued)

Identification Tests

Identification tests involving real or simulated materials may be classified as either a form of performance test or a form of cognitive paper-and-pencil test. Such tests usually involve specimens that must be identified by the student. Examples include breeds of dogs, plant materials, hand tools, and soil types. Specimens with identifying numbers can be arranged two to three feet apart around the perimeter of tables. Students stand next to a “station,” with each specimen serving as a station. The time at each station should be limited, with every student having equal time at each station. The students rotate to the next station until they have come full circle. The test is then complete. The identification test can be matching, fill-in-the-blank, or multiple-choice.

GRADING STUDENTS

Marks or grades are designed to serve as comprehensive measures of student achievement. Most schools require that marks be assigned and reported for each course. It is the responsibility of the teacher of agriculture to report a grade for each student for each grading period.

Many teachers do not like to assign grades. Teachers desire to serve students as guides and counselors. Some believe the role of the counselor is threatened when they judge achievement in assigning grades. Any grading system can be made strong or weak by the extent of dedication of the teachers who use it.

Purpose of Grades

Grades serve as a means of recording and communicating student progress in learning. Students often are motivated to work for grades. There is no harm in this if the grades are a true indication of learning progress. Grades must be accurate, precise measures of achievement in order to minimize misinterpretation of them by students, faculty, parents, and others who use them.

Kinds of Marking Systems

There are two major types of marking systems. Most agriculture teachers report student grades on a system based on the use of a few letter marks. Some still use the more traditional system of marking in percentages.

The percentage system is usually on a scale of O to 100 percent. Often a score somewhere between 60 and 75 percent is regarded as the minimum needed to pass.

The letter system usually consists of five letters: A, B, C, D, and F. The letter system is a less precise system but one with which most people are familiar.

Most often a combination of the percentage system and letter system is used. In this situation grades are assigned using a numerical percent, and then a letter grade is assigned accordingly where grades in the 90s are A ranges, 80s are B ranges, 70s are C ranges, and so on. Each grading system can be used effectively by a teacher to report the degree to which students have mastered needed knowledge.and skills.

Bases for Marking Systems

Teachers of agriculture must consider what information will contribute to decisions about grades. In the traditional sense, grades should reflect the extent to which students have achieved the objectives. Some teachers, however, believe top grades should be given to all students who are working up to their capabilities. Others believe a more difficult course should award a higher percentage of top grades. Classes in which outstanding students are enrolled are often graded higher on the average than classes where students with greater limitations are enrolled. Should better grades be given to reward a student who needs encouragement, or should poorer marks be given to a student who needs to be punished? These issues are difficult to resolve. However, one must keep in mind that if grades are to be valid indicators of achievement, they must be assigned based on acquiring knowledge and skills. The primary basis for assignment of marks is the extent to which objectives have been achieved. Consideration of other factors only lowers the validity of grades as measures of student achievement. If grades are to be measures of accomplishment of objectives, teachers must be sure that objectives have been specified for cognitive learning, affective development, and performance of essential skills.

Factors in Grading

Teachers should develop a grading policy and share it with their students. There is then a clear understanding as to what is expected.

Objectives in agricultural instruction suggest that students should be achieving in their supervised agricultural experience program, in the classroom and laboratory, and in personal development. Figure 14-9 is an example of a grading scale that incorporates these factors in arriving at a mark for a grading period. In the grading scale, weights have been assigned by the teacher to each of three major areas. Teachers may determine the weight for each area based on the objectives of a particular course.

Student assessment

Student name: Grading period:

| Criteria | Points possible | My score |

|---|---|---|

| Supervised agricultural experience Improvement project—points Placement experience—points Records—points |

||

| Subtotal* | 20 | |

| Learning activities Classroom achievement Laboratory performance Notebook |

||

| Subtotal* | 60 | |

| Personal development Cooperation and social habits Responsibility and initiative Leadership and FFA participation |

||

| Subtotal* | 20 | |

| Grand total |

*Students must achieve at least 50% of the possible points In each of the three major areas to satisfactorily complete the course.

A = 90-100 points

B = 80-89 points

C = 70-79 points

D = 60-69 points

F = Below 60 points

Letter grade:

Figure 14-9: Grading scale for agricultural education

Source: Adapted from: Wilson, Richard H. (n.d.) Methods of Student Evaluation. Columbus: The Ohio State University, Department of Agricultural Education, unpublished mimeo, p.20. Used with permission of The Ohio State University and released under CC BY NC SA 4.0.

Grading students requires making decisions about marks for each test, for various affective behavior ratings, for performance evaluations, for completed projects, and other factors. Because most classes in agriculture are relatively small, teachers should refrain from grading on a curve and should instead rate students on the extent to which they achieved what was expected of them. Grades should be combined so that a composite score is obtained which has assigned an appropriate weight to each factor.

One method of grading is to use percents to score each item. Another method is to use letter grades and then average the letter grades based on the following scale: A = 4; B = 3; C = 2; D = 1; F = 0. When plus and minus grades are used, the following scale might be appropriate: A = 11; A- = 10; B+ = 9; B = 8; B- = 7; C+ = 6; C = 5; C- = 4; D+ = 3; D = 2; D- = 1; F = 0. Converting letters to numbers helps in averaging to obtain a composite score.

It is important for the teacher to record several grades during each grading period. A personal development grade should be recorded at least weekly. Record books and notebooks should be evaluated at least twice per grading period. There should be at least one test score recorded per week. Because grades are more reliable when they have been calculated based on many independent measures of achievement, teachers of agriculture are obligated to use a minimum of three to four grades per week from a variety of measures, such as speeches, quizzes, written papers, static displays, tests, skills projects, group projects, and products.

SUMMARY

Evaluation is needed for pretesting, in giving feedback on instructional effectiveness, for motivating students to learn, in student self-appraisal, for better student learning, and for assigning grades to students. Evaluation should be based on objectives. A test plan will help teachers ensure that the evaluation measures the objectives. Types of tests a teacher should be able to use include multiple-choice, short-answer, true-false, matching, and essay tests. Tests need to be properly organized and administered for fair evaluations. Affective and performance assessments should be conducted because these areas relate more closely to the ability of students to secure and maintain employment. A defendable grading system using many independent measures of achievement must be developed and used by teachers.

FOR FURTHER STUDY

- Develop a grading system for use within a class of agriculture students. The system should provide a means of evaluating objectives relating to the supervised agricultural experience program, personal development activities, and classroom and laboratory activities.

- Develop a specification chart that will aid in planning a test for a specific unit of instruction.

- Write a ten-item multiple-choice test.

- Write a five-item short-answer test.

- Write a ten-item true-false test.

- Develop six to ten premise/response matching test items.

- Write an essay question with an ideal response. Underline key concepts in the response. Describe how the item would be scored.

- Write test directions for students for one of the preceding tests.

- Develop a performance test to measure student performance of a skill.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 14.1: Multiple choice question with illustration. Illustration is a board with the direction of grain running perpendicular to the cut. Cut is made on 45 degree angle. The type of saw used to make this cut is a: a. crosscut saw, b. rip saw, c. compass saw, d. coping saw. A is the correct response.

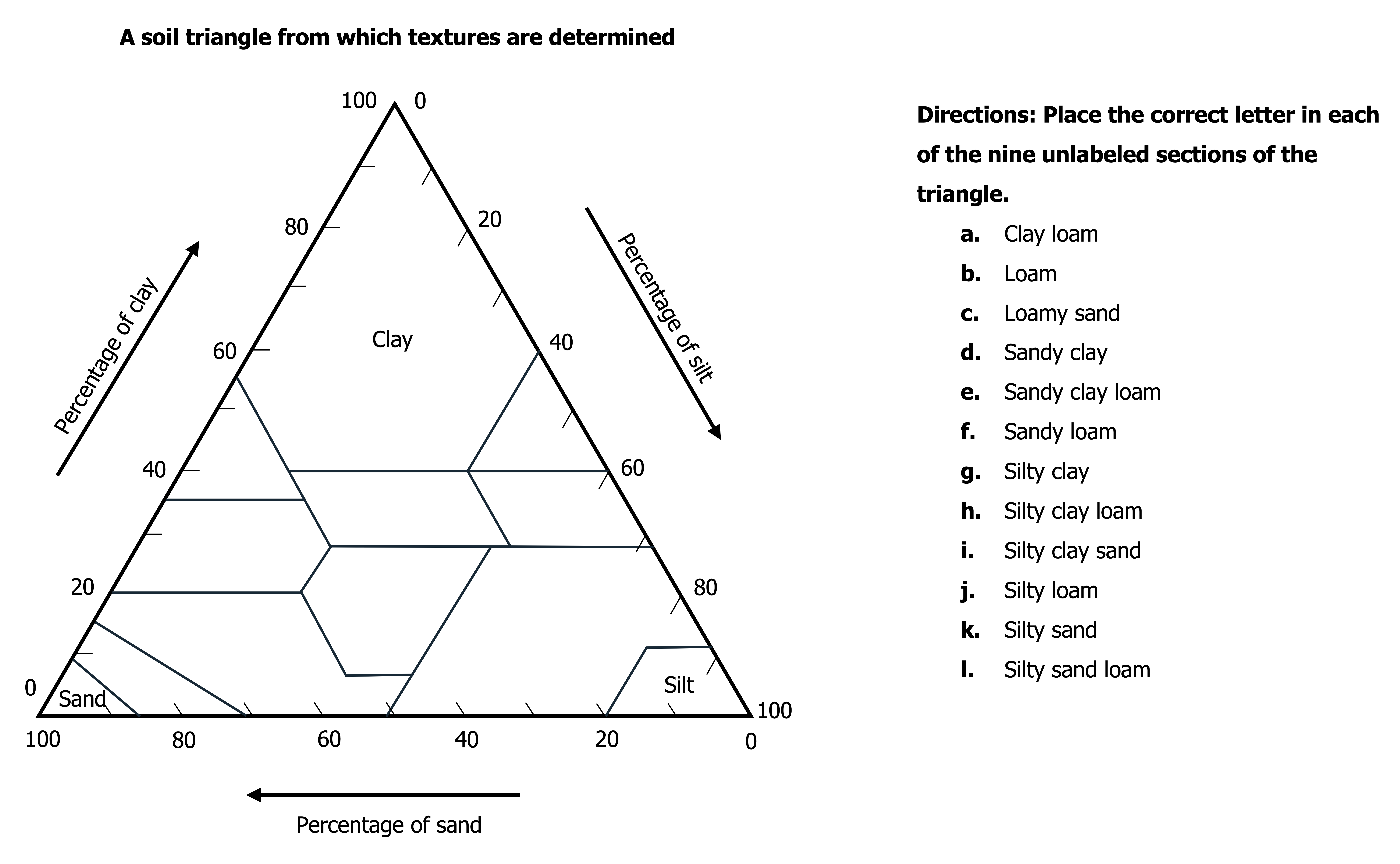

Figure 14.2: A soil triangle from which textures are determined. Directions: place the correct letter in each of the nine unlabeled sections of the triangle. a. clay loam. b. loam. c. loamy sand. d. sandy clay. e. sandy clay loam. f. sandy loam. g. silty clay. h. silty clay loam. i. silty clay sand. j. silty loam. k. silty sand. l. silty sand loam. Triangle diagram is an equilateral triangle. Clockwise: percentage of silt (on the right slant), percentage of sand (on the bottom), and percentage of clay (on the left slant). Arrows for all three sides point to the next section. All sections are numbered from 0 to 100. Clay is in the top corner. Silt is in the bottom right corner. Sand is in the bottom left corner. Seemingly random lines make sections within the triangle.

Figure 14.3: Place a check mark in the space next to each observed behavior. 1. practices good manners, 2. greets people properly, 3. listens courteously, 4. is well groomed, 5. exhibits neat appearance, 6. is considerate of others, 7. practices good judgement.

- Written from material in Stewart, Bob R., Leadership for Agricultural Industry. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978. ↵

- Wiggins, G. The Case for Authentic Assessment. ERIC Document Reproduction Service: ED 328 611. Also see http://webquest.sdsu.edu/rubrics/weblessons.htm. ↵

- Shinn, Glen C., and Weston, Curtis R. Working in Agricultural Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978. ↵