Searching for Patterns: Landscape Ecology

Landscape Ecology Activity Overview

In this activity, your group will explore:

- Geography and Geographic Terms

- Landscape patterns

- Landscape Ecology terms

Many animals and plants require a particular habitat, such as woodlands, to survive. For some of these creatures, the amount of habitat, and the way it connects to similar habitats, can be crucial. The Pileated Woodpecker is one well-known bird species that requires a large amount of connected woodlands to survive (over 4,000 acres for a nesting pair!).

We’ll be going on a scavenger hunt in Google Earth—looking for locations that have experienced certain types of disturbance and change in their landscape. The travels of your Virginia Geocoin will give us the locations to study. For more on the Virginia Geocoin, be sure to read the Getting Started Guide.

Landscape Ecology: Studying Patterns Across Space and Time

Ecosystem: A system that has both the living (plants, animals, bacteria, etc.) and non-living (soil, water, sunlight, etc.) components in a particular area.

Landscape Ecology: The study of how the parts of an ecosystem relate to one another across space and time.

Patches: basic units of similar habitat.

Ecosystems can change across space—habitats can become larger or smaller, or more interconnected, or less interconnected. These changes happen over time, so landscape ecologists look at both space and time when studying patterns and processes, a discipline known as landscape ecology. Scientists who study landscape ecology can measure things like the connectedness or fragmentation of areas of habitat. They employ remote sensing and other geospatial technologies to help them understand how ecosystems change. The basic units ecologists look at are called patches—areas composed of similar habitat (vegetation type, land use, etc.).

Types of Patterns

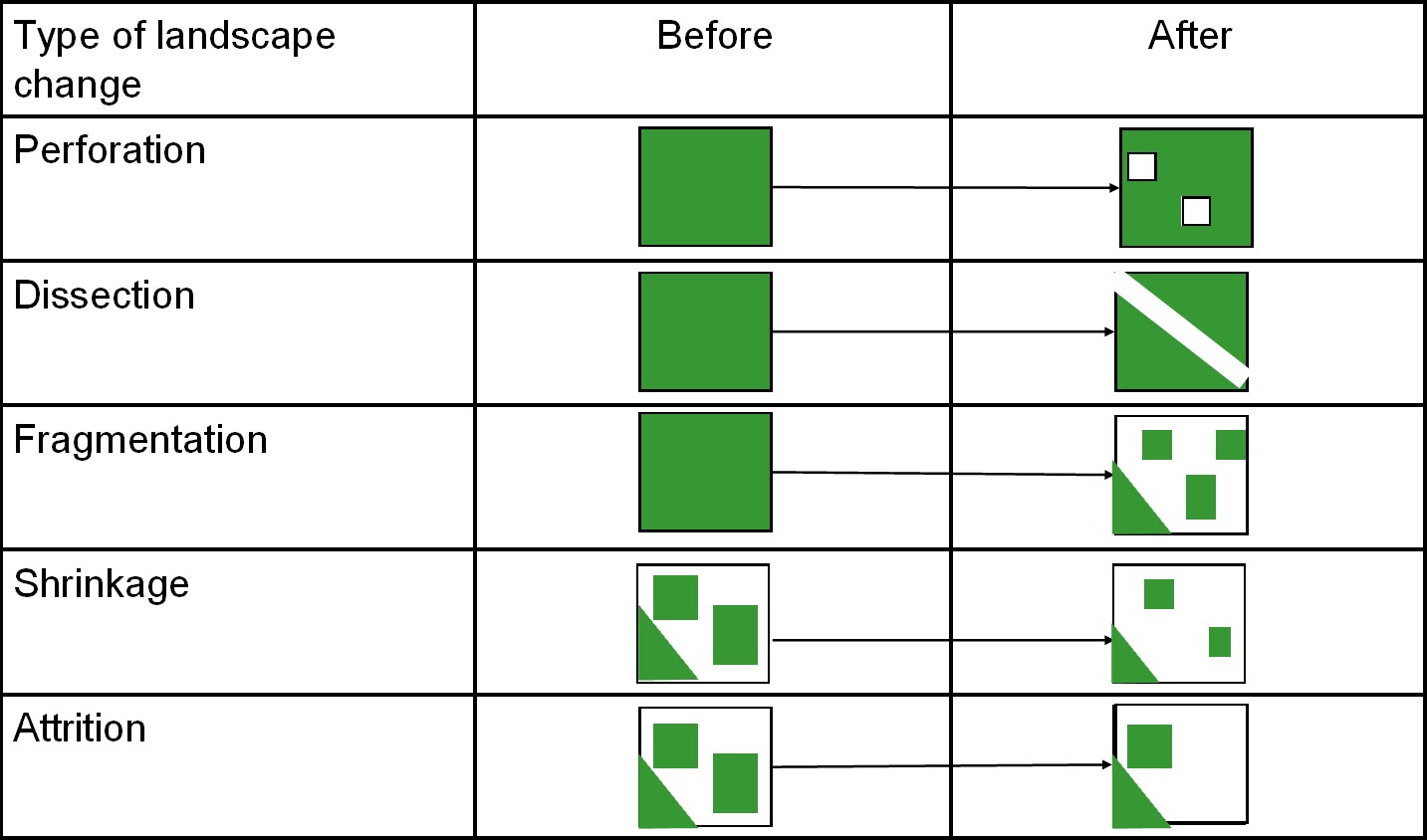

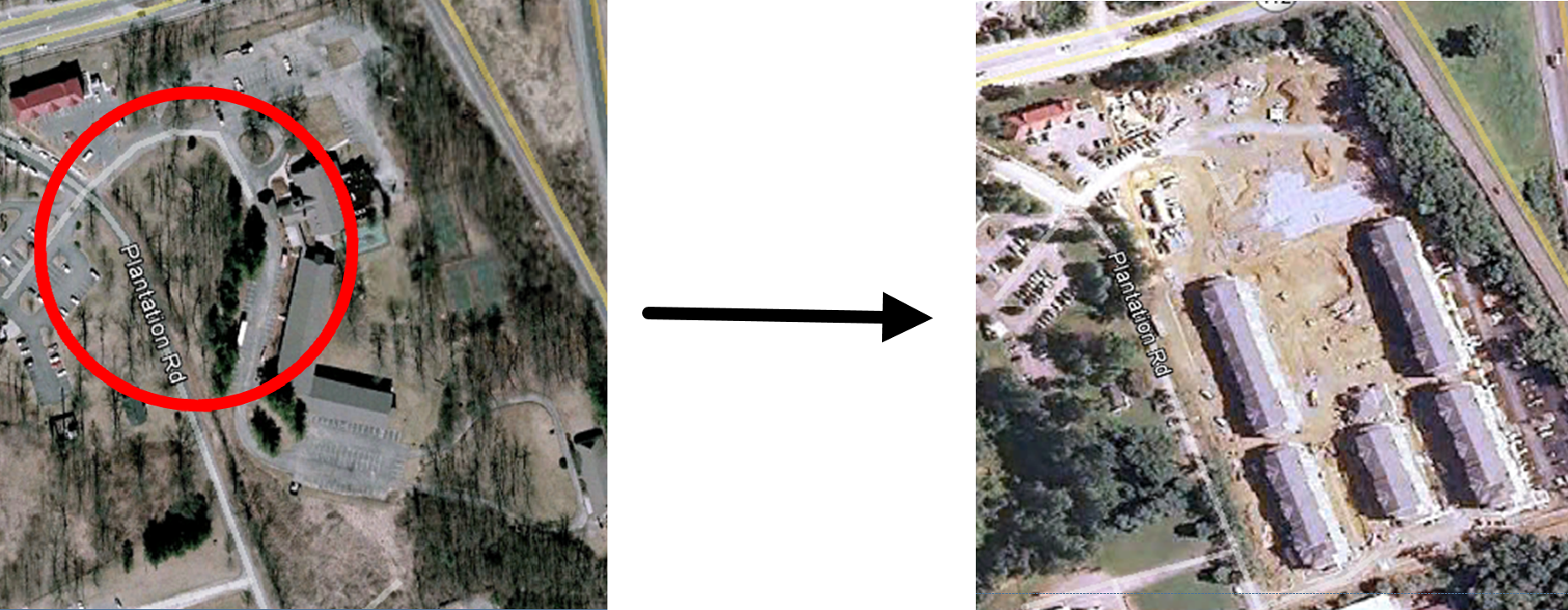

Landscapes don’t often change overnight. There are a few steps we will explore to understand how a landscape can gradually change over time and how these changes affect wildlife like the Pileated Woodpecker. In our scavenger hunt, we’ll be looking for examples of perforation, dissection, fragmentation, shrinkage, and attrition (Figure 3.2). The green represents undisturbed areas (such as woodlands) and the white represents disturbed areas (roads, agriculture, neighborhoods and other development).

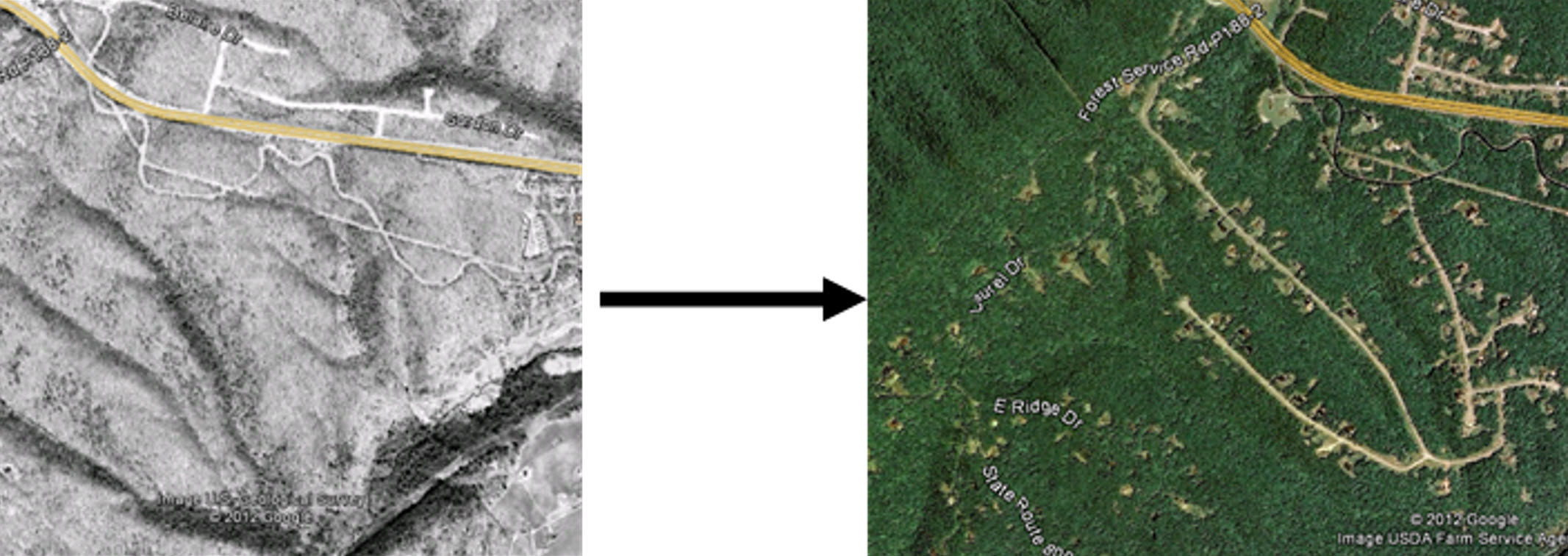

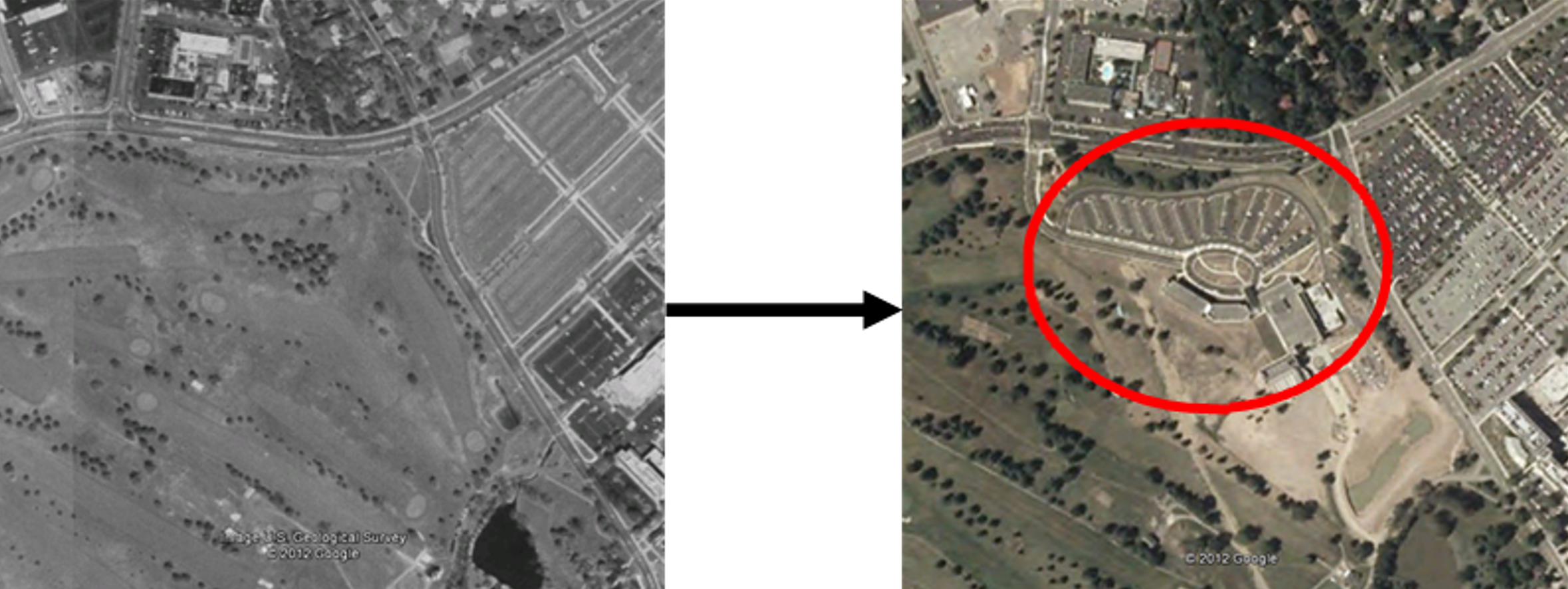

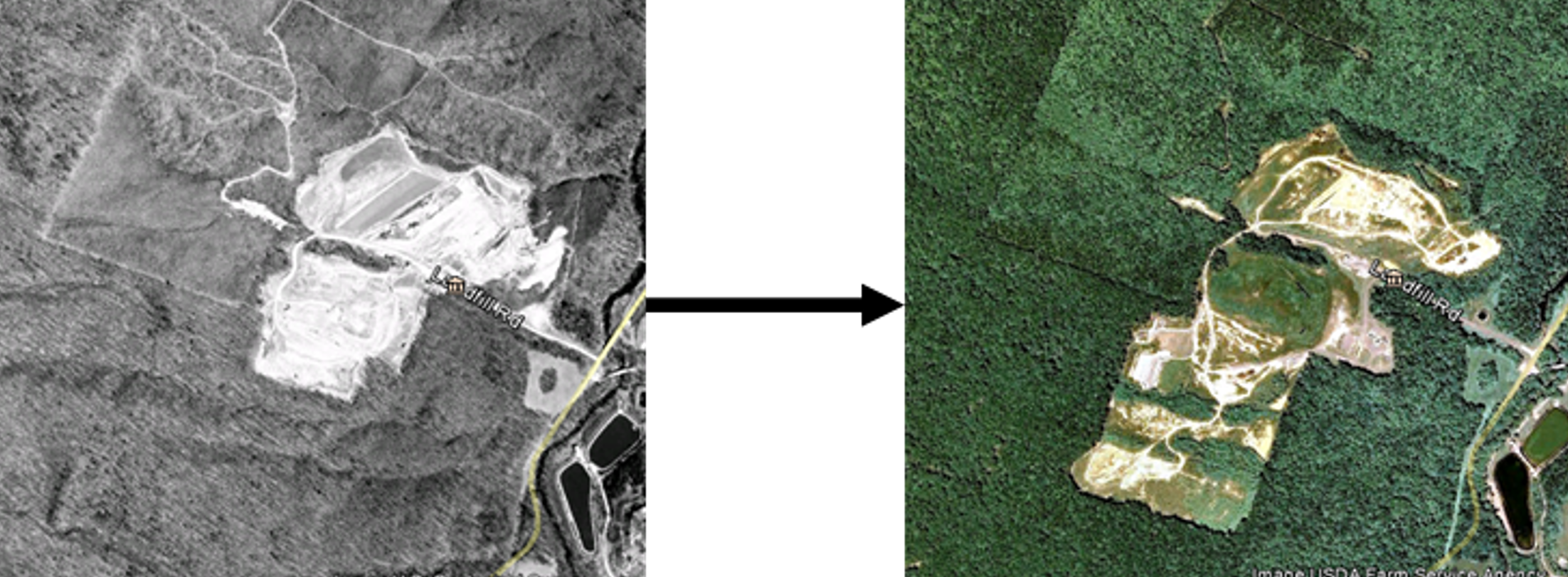

For each of the above types of landscape change, let’s look at some examples that will help you as you search for them in Google Earth. Note: all screen shots are © 2012 Google Earth.

Perforation

Perforation: the creation of small, unconnected gaps within a larger habitat or landscape. This is usually the first step to developing a natural landscape.

These “gaps” in the landscape can be caused by human activities like agriculture, logging, or urban development. Imagine a big, green forest. Perforation is like poking small holes in that forest by cutting down some trees to make space for things like roads, farms, or houses. These small holes can change how animals move around and find food, and it can also make the forest less healthy.

Dissection

Dissection: the division of a landscape into smaller, more isolated segments by linear features such as roads, rivers, or power lines. Like perforation, dissection usually happens as an initial landscape change when an area is first developed.

A common example of dissection is when a highway is built through a forest, it divides the habitat. This could make it harder for animals to travel from one part of their home to another, like if a big wall suddenly appeared in your neighborhood.

Fragmentation

Fragmentation: the breaking up of a landscape into smaller, separate patches. This occurs after perforation or dissection.

The fragmentation process often results in isolated areas that are too small to support populations of certain species. Animals and plants that need big spaces to live might find it tough to survive when their homes are split into tiny parts.

Shrinkage

Shrinkage: when these small pieces of nature start getting even smaller over time. Shrinkage begins to happen after fragmentation.

As a forested area is logged or developed, the remaining patches of forest may get smaller, and there is less room for animals and plants to live. When organisms experience shrinkage, it becomes challenging to find food, water, and necessary space to roam. Think about the nested pair of piliated woodpeckers that need over 4,000 acres to survive!

Attrition

Attrition: when these small pieces of nature disappear completely over time. This is the final step in landscape change.

Attrition is like standing on the last piece of ice in the middle of a pond. When the last piece of ice melts, there is no other ice to stand on. When organisms experience attrition, they become vulnerable to the developed environment and must find somewhere else to live.

Together, these processes describe how landscapes change over time, particularly under the influence of human activities, and highlight the challenges in maintaining biodiversity and ecological integrity in fragmented landscapes.

Up Next: We’ll use a trackable geocoin as a site to search for land changes over time, determine the causes of land change, and think about what impacts that might leave on the environment and nearby communities!

Exploring Patterns

You or someone else in your group should have dropped off a Geocoin in a Geocache a while ago (See Virginia Geocoin Adventure: Getting Started Manual if these terms sound unfamiliar). Now, we can use your Geocoin’s log information to explore spongy moth infestations. We will imagine that your Virginia Geocoin is a mass of spongy moth eggs. We will track the location of the spongy moth egg mass as it moves from place to place (via geocaches) and get an idea of how the spread of the spongy moth could affect that environment.

Note to Leaders: You’ll want to make sure that your Geocoin has traveled to at least 3 (hopefully more) different places before starting this activity. If it has not, then you can always select a different geocoin to complete this exercise. You can conduct a search for Trackable Geocoins on www.geocaching.com/play, and under the ‘Play’ menu, select ‘Trackables.’ You can search for a “Trackable by name” and enter ‘VirginiaView’ (for a listing of all VirginiaView Geocoins), ‘Map@syst’ (for a listing of all Map@syst Geocoins), ‘4H’ (for a listing of all 4H geocoins), or any other geocoin name that you might be familiar with! You can sort these lists by distance traveled (number of miles)! If you have not dropped off trackable Geocoin, then you can use an existing trackable item that is already in circulation.

Required Software: You will want to ensure Google Earth Pro for desktop has been installed before beginning the activity. You can download the desktop version at www.google.com/earth/about/versions/. For a primer on how to navigate Google Earth, download the Google Earth tutorial from virginiaview.cnre.vt.edu/tutorials/.

Note to Leaders: The Scavenger Hunt Activity table is located at the end of the Landscape Ecology section. However, for a downloadable version of the Scavenger Hunt Activity table, visit the Google Spreadsheets link and create as many copies as you need. Also, feel free to modify the spreadsheet to fit your class needs after downloading a copy. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1RKFuJejTaiZl4J0o7PS0aSAKkL2WOGOLSCMebztQGCA/edit?usp=sharing

Hints for completing the scavenger hunt:

Try starting your search near your hometown. You may know of a new development or building in your community—try looking at this area in Google Earth with the time slider to get the hang of looking for landscape changes.

Don’t be tricked! Pictures taken during winter (no leaves), changes in shadows, and changes in color saturation may all look like small landscape changes. Be sure to zoom in enough to the area to decide what is truly landscape change due to development.

Let’s Get Started!

- Log in to www.geocaching.com/play with the account you used when you dropped off the geocoin.

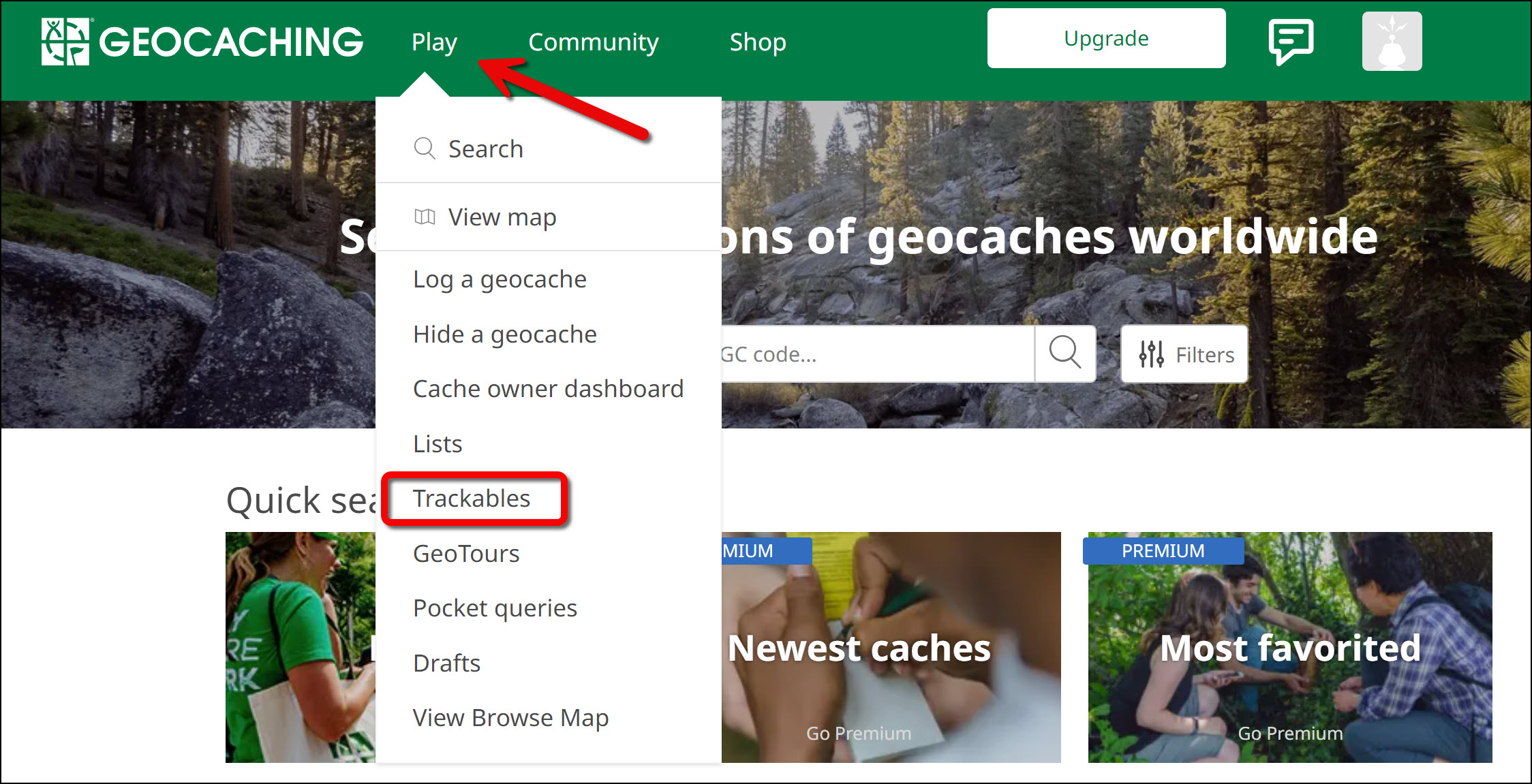

- From the ‘Play’ dropdown menu, select ‘Trackables’ (Figure 3.8).

3.8: Arrow pointing to the ‘Play’ button with its dropdown menu open. A rectangle enclosed on the ‘Trackables’ button. - Enter the tracking code printed on the trackable (ex: XX234XX). Note: Once the secret tracking code is entered, a ‘nickname number’ will appear on the webpage to reference the geocoin. The nickname number is okay to share with others.

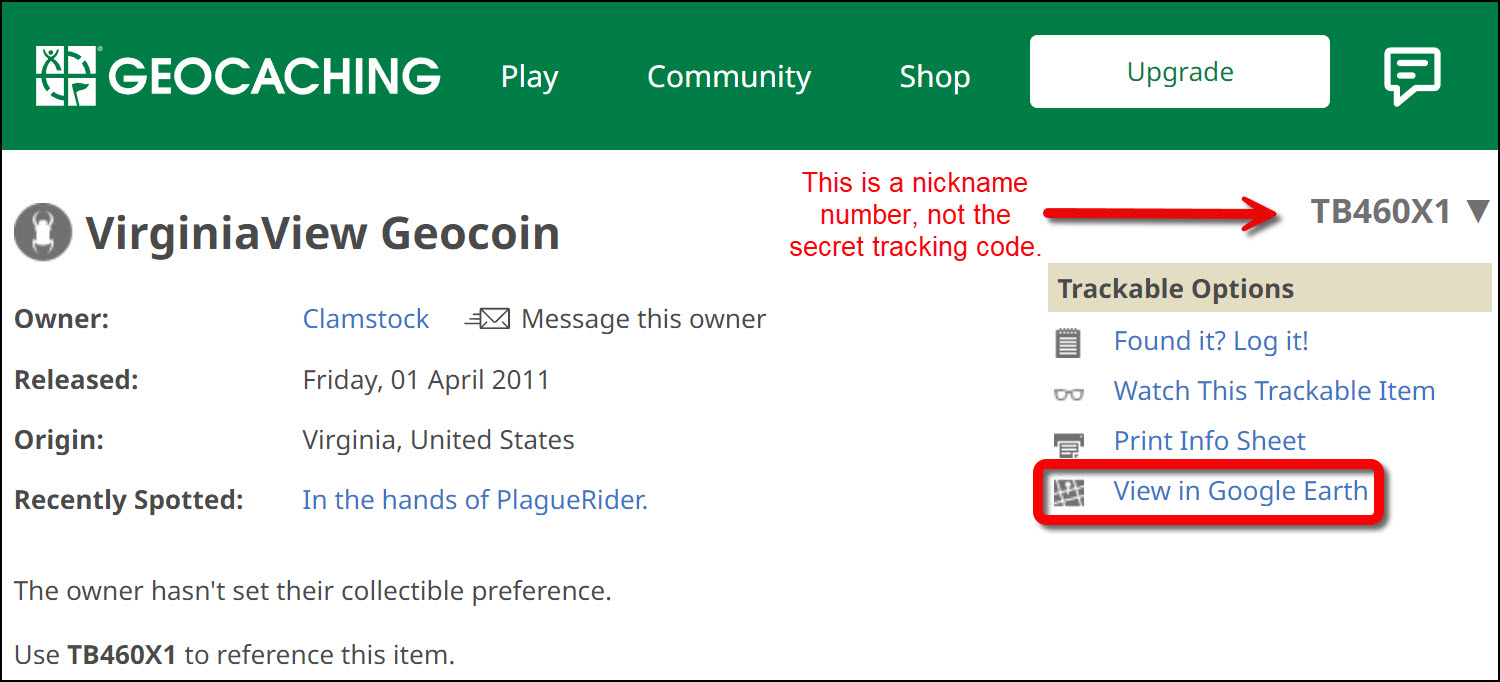

- From the geocoin’s log page, click on ‘View in Google Earth’ under the Trackable Options menu (Figure 3.9). This will generate a KML file for you to download to your computer. Note: Ensure Google Earth Pro for desktop is installed before clicking ‘View in Google Earth.’ You can install the application from www.google.com/earth/about/versions/.

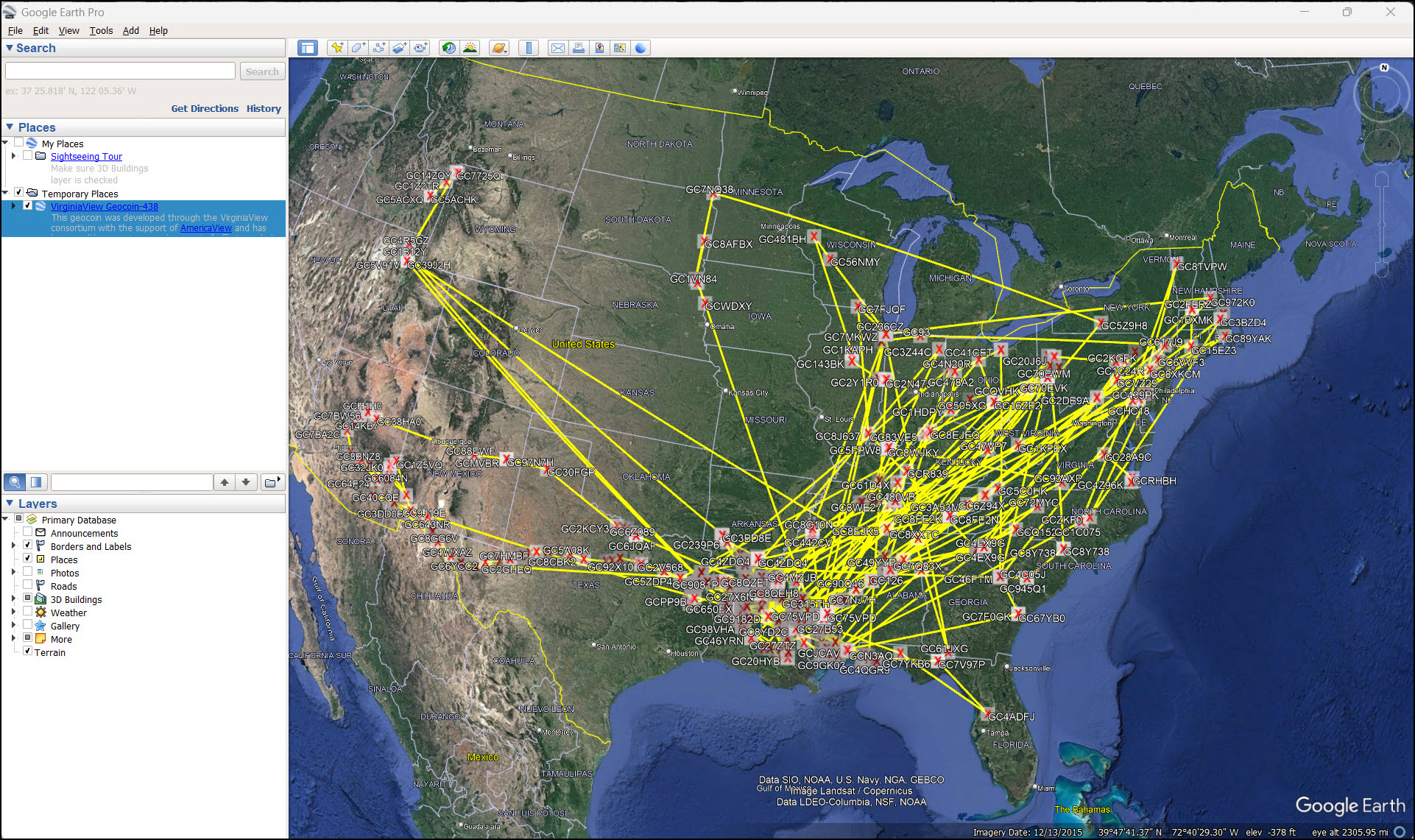

3.9: Upper section of the Geocoin’s log page displaying where to find the ‘View in Google Earth’ link to download the geocoin’s KML file. - After downloading the KML file to your computer, double click on the file to open it with Google Earth Pro for desktop. You should now see yellow tracks for your geocoin on the map (Figure 3.10).

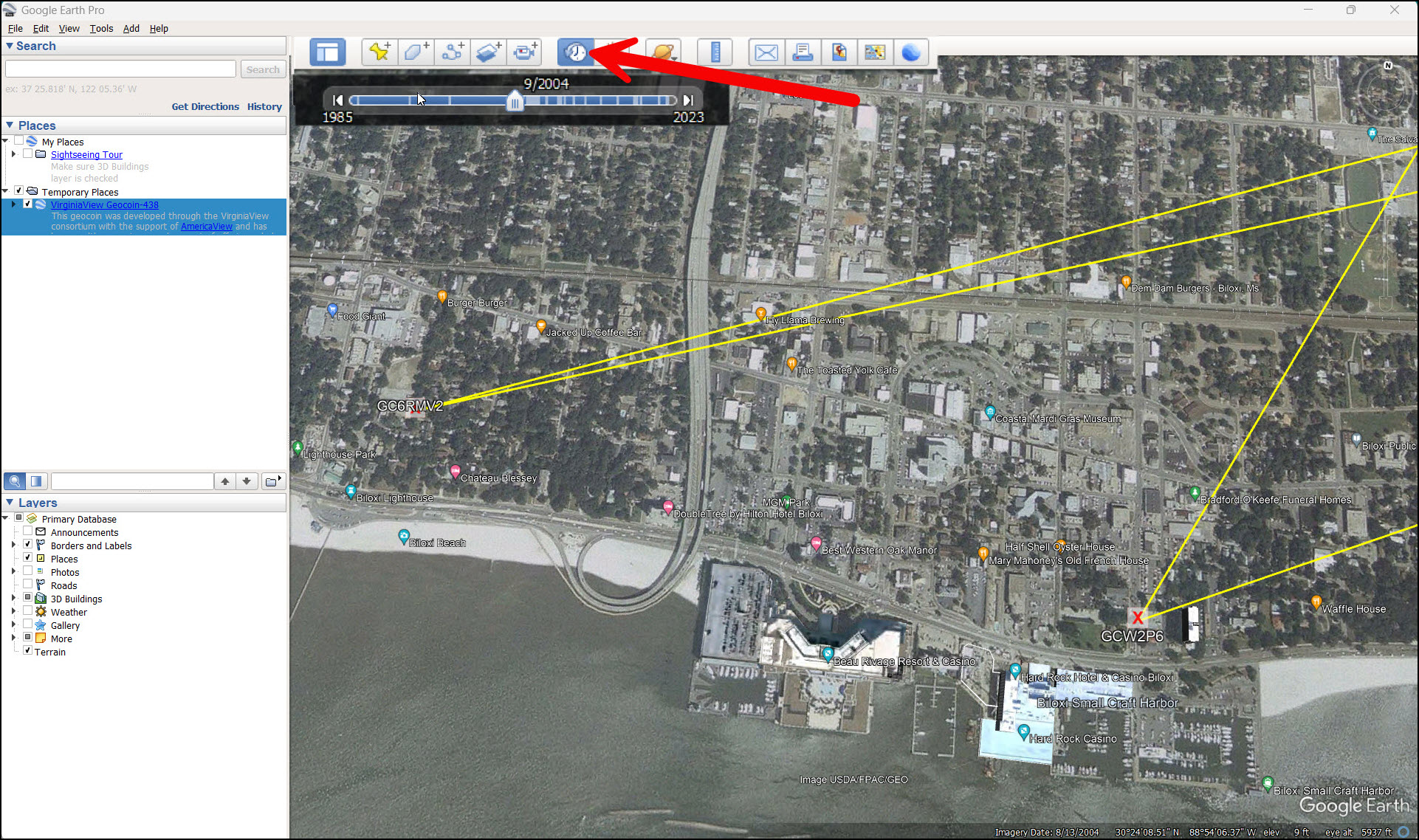

3.10: Google Earth page displaying the geocoin’s travel routes with yellow lines. - You’ll also need to use the historical imagery on Google Earth. To use this tool, click on the Clock symbol at the top menu bar. This brings up the time slider. You can change the date by dragging and sliding (Figure 3.11). Note: Google Earth historic images for your zoomed in area are only available where a light blue color is displayed on the time slider.

3.11: Using historical imagery and the time slider on zoomed in geocoin stops. - Using the historical imagery tool, zoom into areas that are familiar to you and identify changes to the landscape. Then zoom in to stops (points or vertexes) on your geocoin’s journey to discover changes to the landscape over time. Hint: Were new roads added? Did forested areas shrink? Did fields turn into developed areas? If you can’t see any changes over time, try zooming out a bit and looking again.

- Once you see a landscape change, think about what caused the change and figure out which type of landscape change best describes it.

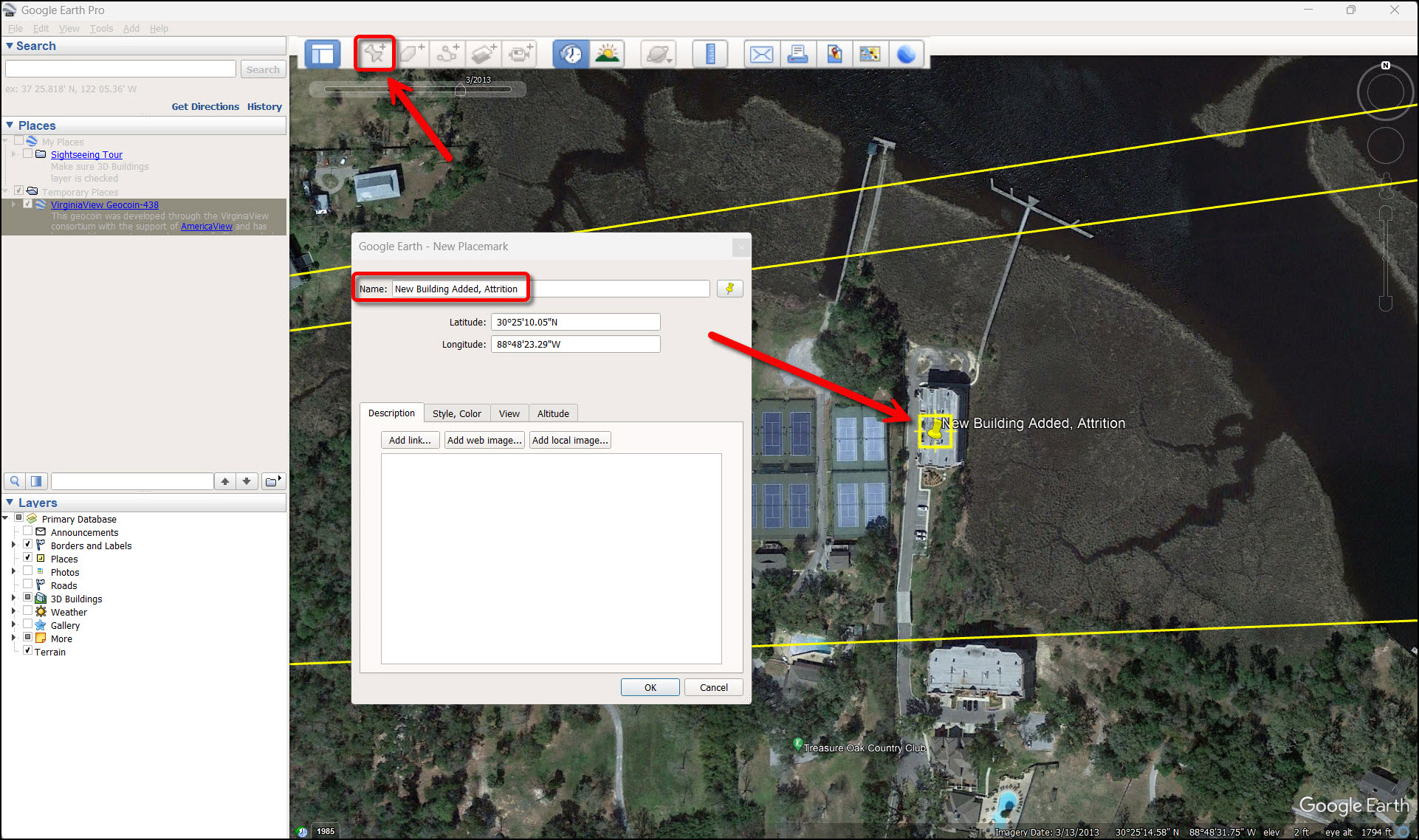

- Use the Add Placemark (Push Pin) tool in Google Earth to mark the location of change. Name the placemark with a cause of change and its category (example: development, attrition). (Figure 3.12).

3.12: Adding a placemark for an area of landscape change near a geocoin stop. - To complete the scavenger hunt, visit the Google link and fill out the spread sheet (https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1RKFuJejTaiZl4J0o7PS0aSAKkL2WOGOLSCMebztQGCA/edit?usp=sharing).

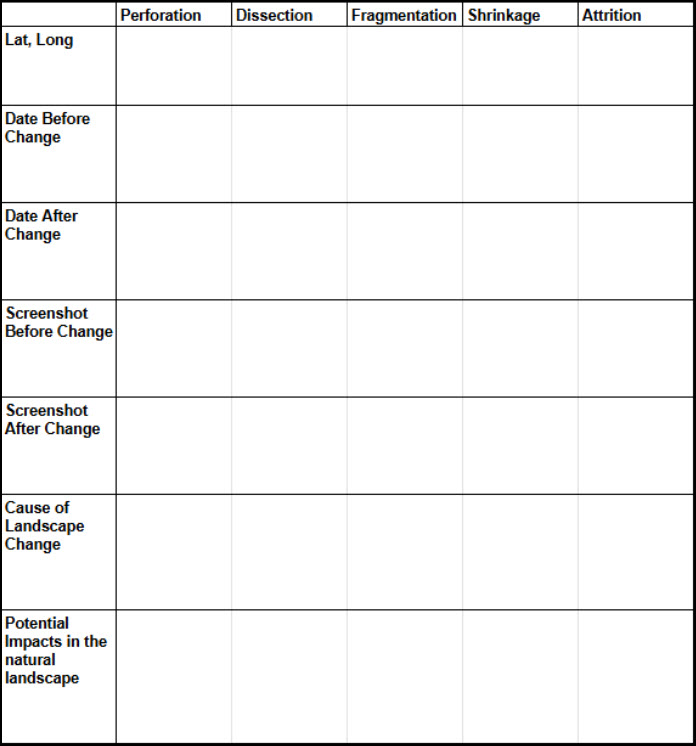

Scavenger Hunt Activity Table.

Note to Leaders: If you are unfamiliar with creating screen shots and pasting them into Microsoft Word, follow the instructions:

Mac Users: https://support.apple.com/en-us/102646

Windows Users: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/learning-center/how-to-screenshot-windows-11

OR you can click on the email button on the top Google Earth menu bar. Select the ‘Graphic View’ (first radio button) option to email yourself a picture of the map. Then you can download the image and insert it into your document.

Resources

Tutorials for using Google Earth:

An Introduction to Google Earth Pro https://virginiaview.cnre.vt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/smGoogle-Earth-Pro-Manual.pdf

Foreman, R.T.T. (1995). Land Mosaics: the ecology of ecosystems and regions. Cambridge University Press. pp. 656.